Mindfulapproaches to Behavior & Mental Health Difficulties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thich Nhat Hanh the Keys to the Kingdom of God Jewish Roots

Summer 2006 A Journal of the Art of Mindful Living Issue 42 $7/£5 Thich Nhat Hanh The Keys to the Kingdom of God Jewish Roots The Better Way to Live Alone in the Jungle A Mindfulness Retreat for Scientists in the Field of Consciousness A Convergence of Science and Meditation August 19–26, 2006 Science studies the brain from your family to a seven-day mindfulness In the beautiful setting of Plum outside, but do we know what happens retreat to learn about our minds using Village, we will enjoy the powerful when we look inside to experience Buddhist teachings and recent scientific energy of one hundred lay and mo- our own minds? Ancient Buddhist findings. nastic Dharma teachers, and enjoy the wisdom has been found to correspond brotherhood and sisterhood of living in During the retreat participants very closely with recent scientific dis- community. Lectures will be in English are invited to enjoy talks by and pose coveries on the nature of reality. Dis- and will be simultaneously translated questions to Zen Master Thich Nhat coveries in science can help Buddhist into French and Vietnamese. Hanh. Although priority will be given meditators, and Buddhist teachings on to neuroscientists and those who work consciousness can help science. Zen in the scientific fields of the brain, the Master Thich Nhat Hanh and the monks mind, and consciousness, everyone is and nuns of Plum Village invite you and welcome to attend. For further information and to register for these retreats: Upper Hamlet Office, Plum Village, Le Pey, 24240 Thenac, France Tel: (+33) 553 584858, Fax: (+33) 553 584917 E-mail: [email protected] www.plumvillage.org Dear Readers, Hué, Vietnam, March 2005: I am sitting in the rooftop restaurant of our lovely hotel overlooking the Perfume River, enjoying the decadent breakfast buffet. -

The Art of Suffering: Questions and Answers the Sangha Carries

Winter/Spring 2014 A Publication of Plum Village Issue 65 $8/€8/£7.50 The Art of Suffering: Questions and Answers by Thich Nhat Hanh Calligraphic Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh’s exhibit in NYC The Sangha Carries Everything interview with Anh-Huong Nguyen Wake Up Spirit Will you help continue the mindful teachings and loving practice of Thich Nhat Hanh? Consider how Thich Nhat Hanh’s gift of mindfulness has brought peace and happiness to you. Then, please join with him to help bring peace and ease suffering throughout the world by becoming a member of the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation with your monthly pledge gift. Working with our loving community, the Foundation works to provide funding for our three North American practice centers “ Don’t worry if you feel you can only do one tiny and Plum Village Monastery, Dharma good thing in one small corner of the cosmos. education and outreach programs, Just be a Buddha body in that one place.” international humanitarian relief assistance, -Thich Nhat Hanh and the “Love & Understanding” program. To join online, and for further information on the Foundation, please visit ThichNhatHanhFoundation.org Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation 2499 Melru Lane, Escondido, CA 92026 • [email protected] • (760) 291-1003 x104 ISSUE NO. 65 - Winter/Spring 2014 Dharma Talk 4 The Art of Suffering: Questions and Answers with Thich Nhat Hanh The Art of Suffering 10 The Sangha Carries Everything: Compassion An Interview with Anh-Huong Nguyen 33 Caring for Our Children by 13 Walking Meditation with Anh-Huong Caring for Ourselves By Garrett Phelan By John R. -

Gongan Collections I 公案集公案集 Gongangongan Collectionscollections I I Juhn Y

7-1 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 7-1 GONGAN COLLECTIONS I COLLECTIONS GONGAN 公案集公案集 GONGANGONGAN COLLECTIONSCOLLECTIONS I I JUHN Y. AHN JUHN Y. (EDITOR) JOHN JORGENSEN COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 7-1 公案集 GONGAN COLLECTIONS I Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 7-1 Gongan Collections I Edited by John Jorgensen Translated by Juhn Y. Ahn Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-10-2 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 7-1 公案集 GONGAN COLLECTIONS I EDITED BY JOHN JORGENSEN TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED BY JUHN Y. AHN i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. -

Thich Nhat Hanh and the Order of Interbeing

True Transmission by Thich Nhat Hanh Awareness of Suffering Dwelling Happily in the Present Moment True Love Guest edited by Mitchell Ratner A Publication of Plum Village Summer 2019 / Issue 81 $12USD/ €11/ £13/ $16AUD A Journal of the Art of Mindful Living in the Tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh Published by Plum Village Issue 81 Summer 2019 Advisor and Editor Sister Annabel, True Virtue Managing Editor Hong-An Tran-Tien Design LuminArts Proofreaders Leslie Rawls Diane Ronayne Dear Thay, dear community, Subscriptions & Marketing Heather Weightman When I first met Thay (Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh) in 1990, I was im- Coordinator mediately captivated by the presence, ease, and joy that seemed to Webmaster Brandy Sacks radiate from him, whether he was giving a Dharma talk or walking Caretaking Council Verena Böttcher in a park. I was then a relatively new practitioner of meditation Natascha Bruckner and mindfulness. Although by conventional standards I was doing Thay Phap Dung well, inwardly I had felt cut off from life, and I had often suffered Marisela Gomez from dissatisfaction, self-doubt, and anxiety. I felt that I could Thu Nguyen learn a lot from Thay. Looking back now at that moment in time, Alipasha Razzaghipour I believe I greatly underestimated the transformations that Thay David Viafora and the Plum Village practices would bring into my life. Volunteers Margaret Alexander Like the Buddha and the early Mahayana teachers, Thay Sarah Caplan had a clear diagnosis and treatment for the prevailing spiritual Barbara Casey illnesses of his time. He often calls what he teaches engaged Miriam Goldberg practice, or engaged Buddhism. -

Dogen and the Koan Tradition : a Tale of Two Shobogenzo Texts Suny Series in Philosophy and Psychotherapy Author: Heine, Steven

cover cover next page > title: Dogen and the Koan Tradition : A Tale of Two Shobogenzo Texts Suny Series in Philosophy and Psychotherapy author: Heine, Steven. publisher: State University of New York Press isbn10 | asin: 0791417735 print isbn13: 9780791417737 ebook isbn13: 9780585077727 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Shobo genzo, Dogen,--1200-1253,--Mana Shobo genzo, Koan. publication date: 1994 lcc: BQ9449.D657H45 1993eb ddc: 294.3/927/092 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Shobo genzo, Dogen,--1200-1253,--Mana Shobo genzo, Koan. cover next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...ents/eBook%20html/Heine,%20Steven%20-%20Dogen%20and%20the%20Koan%20Tradition/files/cover.html[26.08.2009 19:21:52] cover-0 < previous page cover-0 next page > Dogen * and the Koan* Tradition < previous page cover-0 next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...nts/eBook%20html/Heine,%20Steven%20-%20Dogen%20and%20the%20Koan%20Tradition/files/cover-0.html[26.08.2009 19:21:53] cover-1 < previous page cover-1 next page > SUNY Series in Philosophy and Psychotherapy Edited by Sandra A. Wawrytko < previous page cover-1 next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...nts/eBook%20html/Heine,%20Steven%20-%20Dogen%20and%20the%20Koan%20Tradition/files/cover-1.html[26.08.2009 19:21:54] cover-2 < previous page cover-2 next page > Dogen * and the Koan* Tradition A Tale of Two Shobogenzo* Texts Steven Heine STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS < previous page cover-2 next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...nts/eBook%20html/Heine,%20Steven%20-%20Dogen%20and%20the%20Koan%20Tradition/files/cover-2.html[26.08.2009 19:21:54] cover-3 < previous page cover-3 next page > Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1994 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. -

Meeting Life in Plum Village

MEETING LIFE IN PLUM VILLAGE ENGAGING WITH PRECARITY AND PROGRESS IN A MEDITATION CENTER MSc Thesis Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology Specialization: Global Ethnography Leiden University Guido Knibbe – s2470322 Contact: [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. A.L. Littlejohn Second reader: Dr. E. de Maaker CONTENTS Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. iii Distracted ................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction – freedom, progress and our world ................................................................... 3 1.1 Background – the Plum Village tradition .................................................................... 7 2. Practicing global anthropology ............................................................................................ 11 2.1 Researching critically, in multiple directions ............................................................ 12 2.2 Research methods ........................................................................................................ 14 2.3 On learning about a “Buddhist tradition” ................................................................ 19 3. Arrivals ............................................................................................................................... -

New Chan Forum Issue 22

NEW ZEN PERSPECTIVES CH’AN In this issue we look at many issues FORUM from a diversity of perspectives. Shih-fu sets us going by warning us against taking people at their face value. John Crook makes a new proposal asking Could a lay monastery actually work? Simon No. 22 Autumn 2000 Child launches into Dharma teaching Dharma Adviser and leading retreats. John examines The Venerable Ch’an Master European Zen and the place of Ch'an Dr. Sheng-Yen within it. Iris Tute has visited an Teacher Dr. John Crook important conference on Women and (Ch’uan-teng Chien-ti) Buddhism in Germany. Alysun Jones Editors tells us about her experiments in John Crook Pamela Hopkinson teaching meditation to children. Mick Simon Child Parkin's philosophical piece has real Artwork Sophie Templemuir practical implications for us all. And Helen Robinson we have our usual offerings of poems Photographs and artwork. Could it be we are Guo-yuan Fa Shi Ann Brown gradually coming of age? Price: £2.50 CONTENTS Prologue: No going by appearances. Master Sheng-yen 2 Editorial from the Ch'an hall. Chuang Teng Chien Ti 4 A new proposal: a Lay Zen monastic centre. John Crook 5 In the spirit of Ch'an. Simon Child 8 poem: Death is Now Jane Spray 12 The Place of Ch'an in Post Modern Europe. John Crook 14 poem: Multicultural wash Mark Drew 32 Women in Buddhism Iris Tute 33 Teaching meditation to Children Alysun Jones 34 poem: The silence John Crook 36 The Best of Both Sides Mick Parkin 38 poem: July at Maenllwyd. -

Poster HCP Sangha

HEALTHCARE PRACTITIONERS SANGHA Dear Healthcare Practitioners (HCPs), —————————— You are invited to join monastic and SATURDAY lay practitioners in the Plum Village tradition for an online Healthcare Professionals (HCP) Sangha ——- Gathering. JULY 17th Our aspiration is to come together as a community to nourish one another 10:00-12:00 EST through our practice. As we 14:00-16:00 GMT individually and collectively continue to navigate this complex and challenging time, we hope this can be ——- an opportunity to explore together how we can support one another in 2021 our ongoing aspirations for bringing transformation and healing to —————————— ourselves and the communities of which we are part. Registration is not required, please use the Zoom link below to join. Zoom Meeting ID: 937 1112 5408 | Passcode: PV-HCP Please click here to submit questions to inform Sr.Tu Nghiem’s Dharma talk: https://tinyurl.com/cy4t72kv Further details, including schedule, on the following page! HCP SANGHA GATHERING Dear Healthcare Practitioners (HCPs), You are invited to join monastic and lay practitioners in the Plum Village tradition for an online Healthcare Professionals (HCP) Sangha Gathering on Saturday July 17th 10am-12pm EST/14:00-16:00 GMT. Event Description: Our aspiration is to come together as a community to nourish one another through our practice. As we individually and collectively continue to navigate this complex and challenging time, we hope this can be an opportunity to explore together how we can support one another in our ongoing aspirations for bringing transformation and healing to ourselves and the communities of which we are part. -

Brochure Alaska 2019 Mindfulness Retreat

BLOOMING LOTUS SANGHA Awakening Our Hearts - Healing Our Selves 3 Day Mindfulness Retreat With the Monks & Nuns from Plum Village Join us to bring Adlersheim Wilderness Lodge the miracle of healing and mindfulness into Juneau, Alaska your daily life: June 18-20, 2019 • Healing Practices • Nourishing Learn principles and practices that can transform our Meals consciousness and promote deep healing and increased health Opening our Hearts, Healing our Minds, Healing our Bodies • Mindful Breathing, ENJOY DELICIOUS • MEDITATION • DEEP REST Walking, And Eating VEGAN FOOD • MINDFUL MEALS • NOBLE SILENCE * • MINDFUL • SHARING FROM • Total Relaxation MINDFULNESS MOVEMENTS THE HEART IN A • Deep Listening LECTURES & • MINDFUL HIKES & WARM & FRIENDLY & Mindful DHARMA TALKS WALKS IN NATURE ATMOSPHERE Speech BLOOMING LOTUS SANGHA AWAKENING OUR HEARTS - HEALING OUR SELVES MINDFULNESS RETREAT JUNE 18-20, 2019 JUNEAU, ALASKA Join us to manifest healing, nourishment, and peace together as a spiritual family. Come learn how to practice Mindfulness in a friendly & welcoming atmosphere. Relax, enjoy nature, listen to lectures, make new friends, heal and nourish your practice. The historical Buddha said that to be those same principles and practices, health and experience healing we must we can begin to shine the light that look deeply into the causes and brings transformation and healing to conditions that are conducive increase our community and the world health and maximize deep healing. He taught that we should Given the current challenges we face as find the “seeds” of health and healing a society, we know how important it is in ourselves and in others. And when to stay solid and connected to each we find those seeds we should water other. -

A Letter Asking Buddhist Leaders to Support Tsuru for Solidarity

A Letter Asking Buddhist Leaders to Support Tsuru for Solidarity Tsuru for Solidarity, a nonviolent and direct action project, was initially created by Japanese American community leaders Satsuki Ina, Nancy Ukai, and Mike Ishii in conjunction with the March 2019 Pilgrimage to Crystal City, a former WWII internment camp in Texas that housed over 2,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, and Protest at the South Texas Family Residential Center (located 40 miles away in Dilley, Texas). The Dilley facility holds over a thousand asylum seekers, mostly women, children, and infants from Central America and Mexico. Here, the women and children try to sleep on concrete floors while being deliberately prodded by Border Patrol agents all day and night, try to live on two bologna sandwiches for four days whilst denied bathroom visits. These examples of harassment by the Border Patrol are attempts to persuade the refugees to turn back before they have a chance to have an interview with an asylum officer. We have also read inspection reports of numerous facilities – such as the ones in El Paso and Clint, Texas – where children have been denied showers, soap, or toothpaste whilst trying to take care of the younger infants. Administration officials have asserted that basic human hygiene does not have to be afforded these children, while border agents tell these migrants that if they want to drink water, they need to get that from their cell’s toilets; again, to enact our nation’s “tough” deterrence immigration policies favored by some. Fort Sill (Oklahoma) – WWII Japanese American Internment Camp and 2019 Detention Facility for Migrant Children When the Department of Health and Human Services announced on June 11 that up to 1,400 unaccompanied migrant children would be transferred from Texas to Fort Sill, Oklahoma – a former WWII internment camp that held 700 persons of Japanese ancestry, including 90 Buddhist priests – I was heartened to hear that Tsuru for Solidarity was planning to mobilize a second protest on June 24 in Oklahoma. -

The Generation Dharma Teachers

THE GENERATION X 2019 DHARMA TEACHERS CONFERENCE June 12-16, 2019 Great Vow Zen Monastery TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Message from the Planning Committee 2 GenX 2019 Schedule 3 Conference Schedule Day-by-Day 4 Program Details: The Ethical Transformation, Panel on Integrity 7 and Enlightenment About Great Vow Zen Monastery 8 Great Vow Zen Monastery Map 9 Participants List 10 Notes 13 Thank You 17 1 GENX2019 WELCOME Welcome to the 5th Gen X Teachers gathering. What an amazing achievement. We have been meeting as an inter-lineage community, convening different teachers from all different forms of Buddhism, every 2 years since 2011. This community is unique in that it changes every time we meet, it’s never the exact group of teachers coming together. Every one of you helps to create a space for practice on and off the cushions, reflection, dialogue, and networking at these gatherings. It’s an opportunity to drop our teacher roles and relate to each other as peers, friends and fellow dharma practitioners. We encourage people to intentionally reach out and connect with people from different lineages and take the opportunity to sit down for lunch or go for a walk with someone you don’t know. This is your gathering, if you just need time to be in the beautiful landscape that Great Vow is situated in, then please take that time. We hope that the gathering will nourish and inspire you. Thank you all for taking the time out of your busy lives to join us. Blessings from the 2019 Planning committee. -

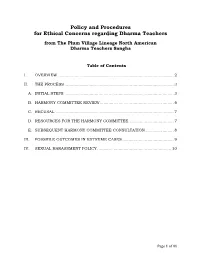

Policy and Procedures for Ethical Concerns Regarding Dharma Teachers

Policy and Procedures for Ethical Concerns regarding Dharma Teachers from The Plum Village Lineage North American Dharma Teachers Sangha Table of Contents I. OVERVIEW ............................................................................................ 2 II. THE PROCESS ....................................................................................... 3 A. INITIAL STEPS. ...................................................................................... 3 B. HARMONY COMMITTEE REVIEW. .......................................................... 6 C. RECUSAL. .............................................................................................. 7 D. RESOURCES FOR THE HARMONY COMMITTEE. ................................... 7 E. SUBSEQUENT HARMONY COMMITTEE CONSULTATION. ...................... 8 III. POSSIBLE OUTCOMES IN EXTREME CASES ......................................... 9 IV. SEXUAL HARASSMENT POLICY ........................................................... 10 Page 1 of 11 I. OVERVIEW This policy establishes a process for addressing perceived ethical lapses by ordained Order of Interbeing Dharma teachers1 in North America who are members2 of the Plum Village Lineage North American Dharma Teachers Council (“Dharma Teachers Sangha”). The Dharma Teachers Sangha Caretaking Council (“Caretaking Council”)3 instituted the process and its Harmony Committee implements its use. The process is intended to support Sanghas and Dharma Teachers in their efforts to reach harmony and understanding. The North American Dharma Teachers