The Adaptation of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness in Francis Ford Coppola's Film Apocalypse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“He Was One of Us” – Joseph Conrad As a Home Army Author

Yearbook of Conrad Studies (Poland) Vol. 13 2018, pp. 17–29 doi: 0.4467/20843941YC.18.002.11237 “HE WAS ONE OF US” – JOSEPH CONRAD AS A HOME ARMY AUTHOR Stefan Zabierowski The University of Silesia, Katowice Abstract: The aim of this article is to show how Conrad’s fiction (and above all the novelLord Jim) influenced the formation of the ethical attitudes and standards of the members of the Polish Home Army, which was the largest underground army in Nazi-occupied Europe. The core of this army was largely made up of young people who had been born around the year 1920 (i.e. after Poland had regained her independence in 1918) and who had had the opportunity to become acquainted with Conrad’s books during the interwar years. During the wartime occupation, Conrad became the fa- vourite author of those who were actively engaged in fighting the Nazi regime, familiarizing young conspirators with the ethics of honour—the conviction that fighting in a just cause was a reward in itself, regardless of the outcome. The views of this generation of soldiers have been recorded by the writers who were among them: Jan Józef Szczepański, Andrzej Braun and Leszek Prorok. Keywords: Joseph Conrad, World War II, Poland, Polish Home Army, Home Army, Warsaw Uprising 1 In order to fully understand the extraordinary role that Joseph Conrad’s novels played in forming the ethical attitudes and standards of those Poles who fought in the Home Army—which was the largest underground resistance army in Nazi-occupied Europe—we must go back to the interwar years, during which most of the members of the generation that was to form the core of the Home Army were born, for it was then that their personalities were formed and—perhaps above all—it was then that they acquired the particular ethos that they had in common. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Lord Jim, by Joseph Conrad

Lord Jim, by Joseph Conrad AUTHOR'S NOTE When this novel first appeared in book form a notion got about that I had been bolted away with. Some reviewers maintained that the work starting as a short story had got beyond the writer's control. One or two discovered internal evidence of the fact, which seemed to amuse them. They pointed out the limitations of the narrative form. They argued that no man could have been expected to talk all that time, and other men to listen so long. It was not, they said, very credible. After thinking it over for something like sixteen years, I am not so sure about that. Men have been known, both in the tropics and in the temperate zone, to sit up half the night 'swapping yarns'. This, however, is but one yarn, yet with interruptions affording some measure of relief; and in regard to the listeners' endurance, the postulate must be accepted that the story was interesting. It is the necessary preliminary assumption. If I hadn't believed that it was interesting I could never have begun to write it. As to the mere physical possibility we all know that some speeches in Parliament have taken nearer six than three hours in delivery; whereas all that part of the book which is Marlow's narrative can be read through aloud, I should say, in less than three hours. Besides--though I have kept strictly all such insignificant details out of the tale--we may presume that there must have been refreshments on that night, a glass of mineral water of some sort to help the narrator on. -

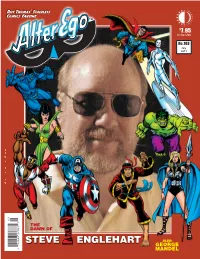

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Charles Marlow the Colonizer, Or, the Ironic Necessity

Teksty Drugie 2014, 1, s. 199-212 Special Issue – English Edition Charles Marlow the Colonizer, or, the Ironic Necessity. Zofia Mitosek Przeł. Jan Pytalski http://rcin.org.pl III ZOflA MITOSEK CHARLES MARLOW THE COLONIZER^ 1 9 9 Zofia Mitosek Charles Marlow the Colonizer, or, the Ironic Necessity ne of the fundamental rules of every ideology is the Zofia Mitosek, Orevision of what has been done in the past, in the professor in the history preceding its emergence. To contradict, however, Institute of Polish Literature of the does not mean to break away. Speaking in the name of University of Warsaw. the truth, ideology attempts to show the illusory cha Visiting p rofessor racter of the former and, at the same time, asses the at the Université de practical dimension of uncovered illusions. The cho M ontréal, C anada; ice of the name post-colonialism is meaningful: even Paris IV-Sorbonne. Dyrektor C entre de though it presents itself not as an ideology but a theory, Civilisation polonaise, researchers who represent this current have a similar Sorbonne. Member critical approach. It is not concerned with resistance, o f the Association with anti-colonialism. It is concerned with reflection, Internationale de an interpretation of the facts, with the “analysis of world Littérature comparée. Her research views constructed from the imperial (hence dominant) interests include point of view”i and checking “how, de facto, it all happe literary theory, ned.” Interestingly, even though post-colonialism was theories of mimesis, created primarily by scholars often coming from for and irony, novel. mer colonies, it is primarly a product of American uni She is the author of among others, versities, a country that, for at least two hundred years Poznanie w powieści, now, feels good about itself, since whatever there was Co z tą ironią?. -

Literary Criticism the 2020-2021 Reading List

University Interscholastic League Student Activities Conference Literary Criticism The 2020-2021 Reading List Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness ǀ Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman ǀ William Wordsworth: selected poems ❖ "I was on the threshold of great things." ~ Kurtz "Dad is never so happy as when he's looking forward to something!" ~ Happy "Dost thou despise the earth where cares abound? / Or, while the wings aspire, are heart and eye / Both with thy nest upon the dewy ground?" ~ Wordsworth ❖ Marlow, Loman, Wordsworth, and the "august light of abiding memories" Conrad's Heart of Darkness In his Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad offers a framework-story, the central narrative of which is spoken by one of five men who share the "bond of the sea." The framing narrative's unnamed narrator does little more than raise and lower the curtain on the young—now experienced—Charles Marlow, who shares his own story while the five sit on the Nellie, a cruising yawl, on the ebbing Thames in the darkness that hangs at the edge of "the lurid glare" of civilization's principal city, the commercial center of a vast colonial empire. The sharing, a story-telling concept foundational to many of Conrad's stories (as is Charlie Marlow himself), necessarily in- cludes a larger audience, the readers—you and me. The unnamed narrator recounts Marlow's beginning the tell- ing of his story: "'I don't want to bother you much with what happened to me personally,' he beg[ins], showing in this remark the weakness of many tellers of tales who seem so often unaware of what their audience would best like to hear; 'yet to understand the effect of it on me you ought to know how I got out there, what I saw, how I went up that river to the place where I first met the poor chap. -

Apocalypse Now, Vietnam and the Rhetoric of Influence Autor(Es): Childs, Jeffrey Publicado Por: Centro De Literatura Portuguesa

Apocalypse now, Vietnam and the rhetoric of influence Autor(es): Childs, Jeffrey Publicado por: Centro de Literatura Portuguesa URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/30048 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/2182-8830_1-2_1 Accessed : 30-Sep-2021 22:18:52 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Apocalypse Now, Vietnam and the Rhetoric of Influence JEFFREY CHILDS Universidade Aberta | Centro de Estudos Comparatistas, Univ. de Lisboa Abstract Readings of Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) often confront the difficulty of having to privilege either its aesthetic context (considering, for instance, its relation to Conrad's Heart of Darkness [1899] or to the history of cinema) or its value as a representation of the Vietnam War. -

THE CONCEPT of the DOUBLE JOSEPH'conrad by Werner

The concept of the double in Joseph Conrad Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bruecher, Werner, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:33:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318966 THE CONCEPT OF THE DOUBLE JOSEPH'CONRAD by Werner Bruecher A Thesis Snbmitted to tHe Faculty of the .' DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE OTHERS TTY OF ' ARIZONA ' STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below ^/viz. -

Conrad and Coppola: Different Centres of Darkness

E. N. DORALL Conrad and Coppola: Different Centres of Darkness (From Southeast Asian Review of English, 1980. in Kimbrough, Robert, ed. Heart of Darkness: Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton & Company, 1988.) When a great artist in one medium produces a work based on a masterpiece in the same or another medium, we can expect interesting results. Not only will the new work be assessed as to its merits and validity as a separate creation, but the older work will also inevitably be reassessed as to its own durability, or relevance to the new age. I am not here concerned with mere adaptations, however complex and exciting they may be, such as operas like Othello, Falstaff and Beatrice et Benedict, or plays like The Innocents and The Picture of Dorian Gray. What I am discussing is a thorough reworking of the original material so that a new, independent work emerges; what happens, for example, in the many Elizabethan and Jacobean plays based on Roman, Italian and English stories, or in plays like Eurydice, Antigone and The Family Reunion, which reinterpret the ancient Greek myths in modern terms. In the cinema, in many ways the least adventurous of the creative arts, we have been inundated by adaptations, some so remote from the original works as to be, indeed, new works in their own right, but so devoid of any merit that one cannot begin to discuss them seriously. But from time to time an intelligent and independent film has been fashioned from the original material. At the moment I can recall only the various film treatments of Hemingway's To Have and Have Not. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

The Dark Night of the Soul: the Archetype and Its Occurrence in Modern Fiction

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 The aD rk Night of the Soul: the Archetype and Its Occurrence in Modern Fiction. Ibry Glyn-francis Theriot Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Theriot, Ibry Glyn-francis, "The aD rk Night of the Soul: the Archetype and Its Occurrence in Modern Fiction." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2577. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2577 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image.