Building and Planting Coastal Sand Dunes: Dune Vegetation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sand Dunes Computer Animations and Paper Models by Tau Rho Alpha*, John P

Go Home U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Sand Dunes Computer animations and paper models By Tau Rho Alpha*, John P. Galloway*, and Scott W. Starratt* Open-file Report 98-131-A - This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this program has been used by the U.S. Geological Survey, no warranty, expressed or implied, is made by the USGS as to the accuracy and functioning of the program and related program material, nor shall the fact of distribution constitute any such warranty, and no responsibility is assumed by the USGS in connection therewith. * U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, CA 94025 Comments encouraged tralpha @ omega? .wr.usgs .gov [email protected] [email protected] (gobackward) <j (goforward) Description of Report This report illustrates, through computer animations and paper models, why sand dunes can develop different forms. By studying the animations and the paper models, students will better understand the evolution of sand dunes, Included in the paper and diskette versions of this report are templates for making a paper models, instructions for there assembly, and a discussion of development of different forms of sand dunes. In addition, the diskette version includes animations of how different sand dunes develop. Many people provided help and encouragement in the development of this HyperCard stack, particularly David M. Rubin, Maura Hogan and Sue Priest. -

Types of Landslides.Indd

Landslide Types and Processes andslides in the United States occur in all 50 States. The primary regions of landslide occurrence and potential are the coastal and mountainous areas of California, Oregon, Land Washington, the States comprising the intermountain west, and the mountainous and hilly regions of the Eastern United States. Alaska and Hawaii also experience all types of landslides. Landslides in the United States cause approximately $3.5 billion (year 2001 dollars) in dam- age, and kill between 25 and 50 people annually. Casualties in the United States are primar- ily caused by rockfalls, rock slides, and debris flows. Worldwide, landslides occur and cause thousands of casualties and billions in monetary losses annually. The information in this publication provides an introductory primer on understanding basic scientific facts about landslides—the different types of landslides, how they are initiated, and some basic information about how they can begin to be managed as a hazard. TYPES OF LANDSLIDES porate additional variables, such as the rate of movement and the water, air, or ice content of The term “landslide” describes a wide variety the landslide material. of processes that result in the downward and outward movement of slope-forming materials Although landslides are primarily associ- including rock, soil, artificial fill, or a com- ated with mountainous regions, they can bination of these. The materials may move also occur in areas of generally low relief. In by falling, toppling, sliding, spreading, or low-relief areas, landslides occur as cut-and- La Conchita, coastal area of southern Califor- flowing. Figure 1 shows a graphic illustration fill failures (roadway and building excava- nia. -

Gabion Retaining Walls with Alternate Fill Materials

Gabion Retaining Walls with Alternate Fill Materials IGC 2009, Guntur, INDIA GABION RETAINING WALLS WITH ALTERNATE FILL MATERIALS K.S. Beena Reader, School of Engineering, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin–682022, India. E-mail: [email protected] P.K. Jayasree Lecturer in Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, Trivandrum–695 016, India. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Although gabions have been used from ancient times, it is only in the last few decades that their wide spread use has lead them to become an accepted construction material in Civil Engineering. Gabion retaining walls are mass gravity structure made up of strong mesh containers known as gabion boxes, filled with quarry stone. Considering the cost and scarcity of quarry stones, the replacement of it with some other cheaper material will make the construction more economical. This aspect is studied here. Considering the specific gravity, friction, cost and availability, quarry dust and red soil was selected as the fill material. Model gabion retaining walls were constructed for the purpose in which, different combinations of quarry dust, red soil and coarse aggregate were taken as the filling material. Analyzing the lateral deformations of various cases, it can be concluded that a 50%–50% combination of alternative material and aggregate will perform better than the coarse aggregate alone, considering the cost of construction. 1. INTRODUCTION dry stone gravity mass wall made of gabion boxes. They are cost effective, environmental friendly and durable structures. Retaining walls, one of the major geotechnical applications, Because of these reasons gabions are widely used now days are mainly used in the case of highways and railways to all over the world. -

Landslide Triggering Mechanisms

kChapter 4 GERALD F. WIECZOREK LANDSLIDE TRIGGERING MECHANISMS 1. INTRODUCTION 2.INTENSE RAINFALL andslides can have several causes, including Storms that produce intense rainfall for periods as L geological, morphological, physical, and hu- short as several hours or have a more moderate in- man (Alexander 1992; Cruden and Vames, Chap. tensity lasting several days have triggered abun- 3 in this report, p. 70), but only one trigger (Varnes dant landslides in many regions, for example, 1978, 26). By definition a trigger is an external California (Figures 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3). Well- stimulus such as intense rainfall, earthquake shak- documented studies that have revealed a close ing, volcanic eruption, storm waves, or rapid stream relationship between rainfall intensity and acti- erosion that causes a near-immediate response in vation of landslides include those from California the form of a landslide by rapidly increasing the (Campbell 1975; Ellen et al. 1988), North stresses or by reducing the strength of slope mate- Carolina (Gryta and Bartholomew 1983; Neary rials. In some cases landslides may occur without an and Swift 1987), Virginia (Kochel 1987; Gryta apparent attributable trigger because of a variety or and Bartholomew 1989; Jacobson et al. 1989), combination of causes, such as chemical or physi- Puerto Rico (Jibson 1989; Simon et al. 1990; cal weathering of materials, that gradually bring the Larsen and Torres Sanchez 1992)., and Hawaii slope to failure. The requisite short time frame of (Wilson et al. 1992; Ellen et al. 1993). cause and effect is the critical element in the iden- These studies show that shallow landslides in tification of a landslide trigger. -

Slope Stability 101 Basic Concepts and NOT for Final Design Purposes! Slope Stability Analysis Basics

Slope Stability 101 Basic Concepts and NOT for Final Design Purposes! Slope Stability Analysis Basics Shear Strength of Soils Ability of soil to resist sliding on itself on the slope Angle of Repose definition n1. the maximum angle to the horizontal at which rocks, soil, etc, will remain without sliding Shear Strength Parameters and Soils Info Φ angle of internal friction C cohesion (clays are cohesive and sands are non-cohesive) Θ slope angle γ unit weight of soil Internal Angles of Friction Estimates for our use in example Silty sand Φ = 25 degrees Loose sand Φ = 30 degrees Medium to Dense sand Φ = 35 degrees Rock Riprap Φ = 40 degrees Slope Stability Analysis Basics Explore Site Geology Characterize soil shear strength Construct slope stability model Establish seepage and groundwater conditions Select loading condition Locate critical failure surface Iterate until minimum Factor of Safety (FS) is achieved Rules of Thumb and “Easy” Method of Estimating Slope Stability Geology and Soils Information Needed (from site or soils database) Check appropriate loading conditions (seeps, rapid drawdown, fluctuating water levels, flows) Select values to input for Φ and C Locate water table in slope (critical for evaluation!) 2:1 slopes are typically stable for less than 15 foot heights Note whether or not existing slopes are vegetated and stable Plan for a factor of safety (hazards evaluation) FS between 1.4 and 1.5 is typically adequate for our purposes No Flow Slope Stability Analysis FS = tan Φ / tan Θ Where Φ is the effective -

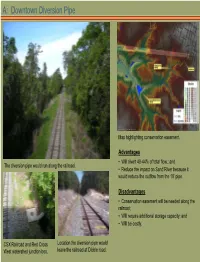

B1: Extend Existing Pipe

A: Downtown Diversion Pipe b c Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 with modifications Map highlighting conservation easement. Advantages • Will divert 40-44% of total flow.; and The diversion pipe would run along the railroad. • Reduce the impact on Sand River because it would reduce the outflow from the 10’ pipe. Disadvantages • Conservation easement will be needed along the railroad; • Will require additional storage capacity; and • Will be costly. CSX Railroad and Red Cross Location the diversion pipe would West watershed junction box. leave the railroad at Dibble road. B1: Extend Existing Pipe Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 Map showing the suggested extension of the pipe. Section of the alterations made to the canyon in order to extend the existing pipe. Advantages • Minimizes amount of new sediment from entering Barton’s Pond; • Easiest method to stabilize the canyon; and • Could be constructed without any additional permits. Drawbacks • Does not dissipate the force of the flow of water or energy; and • The problem is shifted downstream. Considerations Existing canyon walls that The existing pipe that would be • Flow still needs to be returned to the surface. would be filled in and stabilized extended through the canyon of to extend the pipe. Sand River B2: Gabion Baskets as an Erosion Solution Flow a Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 Pipe Permeable Geotextile Fabric d b Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 with modifications Source: Woolpert, Inc. 2006 Sections of the gabions along Sand River a - Section the length of the section of proposed gabions b - Section of a gabion dam Advantages c - Section of the gabion walls with permeable geotextile fabric • Ease of handling and transportation; d - Section of gabion walls without permeable layer against the earth • Speed of construction; • Aesthetically more pleasing than some options; • Provides more natural stream pattern and profile; • Dissipates the energy of the stream; and • If properly constructed, vegetated gabions strengthen with time. -

Sand Fencing

StormSmart Properties Fact Sheet 6: Sand Fencing The coast is a very dynamic environment and coastal shorelines—especially beaches, dunes, and banks—change constantly in response to wind, waves, tides, and other factors such as seasonal variation, sea level rise, and human alterations to the shoreline system. Consequently, many coastal properties are at risk from storm damage, erosion, and flooding. Inappropriate shoreline stabilization methods can actually do more harm than good by exacerbating beach erosion, damaging neighboring properties, impacting marine habitats, and diminishing the capacity of beaches, dunes, and other natural landforms to protect inland areas from storm damage and flooding. StormSmart Properties—part of the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management’s (CZM) StormSmart Coasts Program—provides coastal property owners with important information on a range of shoreline stabilization techniques that can effectively reduce erosion and storm damage while minimizing impacts to shoreline systems. This information is intended to help property owners work with consultants and other design professionals to select the best option for their circumstances. What Is Sand Fencing? Sand fencing, also called snow fencing, is No shoreline stabilization option permanently stops all erosion or designed to help capture sand to build storm damage. The level of protection provided depends on the option dunes. It is typically made of thin, wooden chosen, project design, and site-specific conditions such as the slats that are connected with twisted wire exposure to storms. All options require maintenance, and many also to wooden or metal stakes. While other require steps to address adverse impacts to the shoreline system, fence materials such as plastic, called mitigation. -

Step 2-Soil Mechanics

Step 2 – Soil Mechanics Introduction Webster defines the term mechanics as a branch of physical science that deals with energy and forces and their effect on bodies. Soil mechanics is the branch of mechanics that deals with the action of forces on soil masses. The soil that occurs at or near the surface of the earth is one of the most widely encountered materials in civil, structural and architectural engineering. Soil ranks high in degree of importance when compared to the numerous other materials (i.e. steel, concrete, masonry, etc.) used in engineering. Soil is a construction material used in many structures, such as retaining walls, dams, and levees. Soil is also a foundation material upon which structures rest. All structures, regardless of the material from which they are constructed, ultimately rest upon soil or rock. Hence, the load capacity and settlement behavior of foundations depend on the character of the underlying soils, and on their action under the stress imposed by the foundation. Based on this, it is appropriate to consider soil as a structural material, but it differs from other structural materials in several important aspects. Steel is a manufactured material whose physical and chemical properties can be very accurately controlled during the manufacturing process. Soil is a natural material, which occurs in infinite variety and whose engineering properties can vary widely from place to place – even within the confines of a single construction project. Geotechnical engineering practice is devoted to the location of various soils encountered on a project, the determination of their engineering properties, correlating those properties to the project requirements, and the selection of the best available soils for use with the various structural elements of the project. -

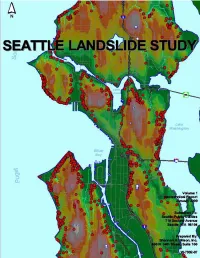

Landslide Study

Department of Planning and Development Seattle Landslide Study TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1. GEOTECHNICAL REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PREFACE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose 1.2 Scope of Services 1.3 Report Organization 1.4 Authorization 1.5 Limitations PART 1. LANDSLIDE INVENTORY AND ANALYSES 2.0 GEOLOGIC CONDITIONS 2.1 Topography 2.2 Stratigraphy 2.2.1 Tertiary Bedrock 2.2.2 Pre-Vashon Deposits 2.2.3 Vashon Glacial Deposits 2.2.4 Holocene Deposits 2.3 Groundwater and Wet Weather 3.0 METHODOLOGY 3.1 Data Sources 3.2 Data Description 3.2.1 Landslide Identification 3.2.2 Landslide Characteristics 3.2.3 Stratigraphy (Geology) 3.2.4 Landslide Trigger Mechanisms 3.2.5 Roads and Public Utility Impact 3.2.6 Damage and Repair (Mitigation) 3.3 Data Processing 4.0 LANDSLIDES 4.1 Landslide Types 4.1.1 High Bluff Peeloff 4.1.2 Groundwater Blowout 4.1.3 Deep-Seated Landslides 4.1.4 Shallow Colluvial (Skin Slide) 4.2 Timing of Landslides 4.3 Landslide Areas 4.4 Causes of Landslides 4.5 Potential Slide and Steep Slope Areas PART 2. GEOTECHNICAL EVALUATIONS 5.0 PURPOSE AND SCOPE 5.1 Purpose of Geotechnical Evaluations 5.2 Scope of Geotechnical Evaluations 6.0 TYPICAL IMPROVEMENTS RELATED TO LANDSLIDE TYPE 6.1 Geologic Conditions that Contribute to Landsliding and Instability 6.2 Typical Approaches to Improve Stability 6.3 High Bluff Peeloff Landslides 6.4 Groundwater Blowout Landslides 6.5 Deep-Seated Landslides 6.6 Shallow Colluvial Landslides 7.0 DETAILS REGARDING IMPROVEMENTS 7.1 Surface Water Improvements 7.1.1 Tightlines 7.1.2 Surface Water Systems - Maintenance -

Cutting Soil Mechanics

Dredging Processes The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock Soil Mechanics Dr.ir. Sape A. Miedema The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock - Soil Mechanics Copyright © Dr.ir. S.A. Miedema Page 3 of 64 The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock - Soil Mechanics Dredging Processes The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock Soil Mechanics By Dr.ir. Sape A. Miedema Copyright © Dr.ir. S.A. Miedema Page 4 of 64 The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock - Soil Mechanics Dredging Processes The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock Soil Mechanics Copyright © Dr.ir. S.A. Miedema Page 5 of 64 The Cutting of Sand, Clay & Rock - Soil Mechanics Preface Lecture notes for the course OE4626 Dredging Processes, for the MSc program Offshore & Dredging Engineering, at the Delft University of Technology. By Dr.ir. Sape A. Miedema, Sunday, January 13, 2013 In dredging, trenching, (deep sea) mining, drilling, tunnel boring and many other applications, sand, clay or rock has to be excavated. The productions (and thus the dimensions) of the excavating equipment range from mm3/sec - cm3/sec to m3/sec. In oil drilling layers with a thickness of a magnitude of 0.2 mm are cut, while in dredging this can be of a magnitude of 0.1 m with cutter suction dredges and meters for clamshells and backhoe’s. Some equipment is designed for dry soil, while others operate under water saturated conditions. Installed cutting powers may range up to 10 MW. For both the design, the operation and production estimation of the excavating equipment it is important to be able to predict the cutting forces and powers. -

Petrographic and Engineering Properties of Loess

BNGINEERING MONOGRAPHS No. 28 United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF RECLAMATION PETROGRAPHIC AND ENGINEERING PROPERTIES OF LOESS by H. J. Gibbs and W. Y. Holland November 1960 $1.00 ~ BUREAU OF RfCLAMA nON l' Cr~~ DENVER UBf!ARY If t (/l I'I'II~'IIIII~/II"~III'920251b3 tl J t, \r , ;;"" 1; "," I. I ,' ;' ~'", r '.'" United States Department of the Interior 'Jo' 0 I .'.~!1 .~ j FRED A. SEA TON, Secretary Bureau of Reclamation FLOYD E. DOMINY, COMMISSIONER GRANT BLOODGOOD, Assistant Commissioner and Chief Engineer Engineering Monograph No. 28 PETROGRAPHIC AND ENGINEERING PROPERTIES OF LOESS by H. J. Gibbs, Head, Special Investigations and Research Section Earth Laboratory Branch and W. Y. Holland, Head, Petrographic Laboratory Section, Chemical Engineering Laboratory Branch Commissioner's Office, Denver, Colorado Technical Information Branch Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado ENGINEERING MONOGRAPHS are published in lirnit~d ~@ition~for till! tl!chnicA.l !t!.ff of the Bureau of Reclamation and interested technical circles in Government and private agencies. Their purpose is to record devel- opments, innovations, and progress in the engineering and scientific techniques and practices that are employed in the planning, design, construction, and operation of Recla- mation structures and equipment. Copies may be obtained from the Bureau of Recla- mation' Denver Federal Center, Denver, Colorado, and Washington, D. C. CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION. 1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF LOESS. 1 ORIGIN OF LOESS. 4 DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF LOESS. 6 Type of Matrix. 7 Cementation. 8 Particle Shape. 8 Granular Components. 9 Grain Coatings. 9 OBSERVATION OF PHYSICAL PROPERTIES. 9 Location of Engineering Studies. -

Sand in Hawai`I

Sand in Hawai`i Jodi N. Harney Ph.D. Student, Coastal Geology Group Dept. of Geology & Geophysics, University of Hawaii Sand composition Beaches in Hawaii may be made of 'black sand' derived from the erosion of volcanic rocks, of 'white sand' made by marine organisms, or a mixture of both. On the windward side of the Big Island, for example, black sand beaches are very common. The beach at South Point is almost entirely green sand composed of olivine, a common mineral found in the volcanic rocks here in Hawaii. On the Kona coast of the Big Island and on the other islands, the beaches have a range of mixed compositions, some with a high volcanic (detrital) component, some dominated by calcareous (reef-derived) sediment. Beach and submarine sands in Kailua Bay on windward Oahu (my research area) are almost entirely composed of calcarous, reef-derived material. On average, only about 5% of the sand grains are volcanic minerals or rock fragments. Every beach is unique and has its own source and type of sediments. Makena ('Big Beach'), Maui Hanakapiai Beach, Napali coast, Kauai Because Hawaii does not have a continental source of quartz sand like mainland beaches, the 'white' beaches and marine sediments here in the islands are primarily composed of the carbonate shells and skeletons of marine organisms, such as corals, algae, molluscs, foraminifera, echinoderms, and bryozoans. Sand-sized fragments of coralline algae, coral, and the calcareous green alga Halimeda Sand-sized fragments of molluscs, foraminifera, and echinoderm spines We can determine the composition of any sand sample by embedding it in clear epoxy, making a thin section, and looking at it with a petrographic microscope.