The Court Will Also Reserve Judgment on Plaintiffs' Joint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Benzodiazephine Use, Abuse, and Detection

Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, the leading clinical diagnostics company, is committed to providing clinicians with the vital information they need for the accurate diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of patients. Our comprehensive portfolio of performance-driven systems, unmatched menu offering and IT solutions, in conjunction with highly responsive service, is designed to streamline workflow, enhance operational efficiency and support improved patient care. Syva, EMIT, EMIT II, EMIT d.a.u., and all associated marks are trademarks of General Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc. All Drugs other trademarks and brands are the Global Division property of their respective owners. of Abuse Siemens Healthcare Product availability may vary from Diagnostics Inc. country to country and is subject 1717 Deerfield Road to varying regulatory requirements. Deerfield, IL 60015-0778 Please contact your local USA representative for availability. www.siemens.com/diagnostics Siemens Global Headquarters Global Siemens Healthcare Headquarters Siemens AG Understanding Wittelsbacherplatz 2 Siemens AG 80333 Muenchen Healthcare Sector Germany Henkestrasse 127 Benzodiazephine Use, 91052 Erlangen Germany Abuse, and Detection Telephone: +49 9131 84 - 0 www.siemens.com/healthcare www.usa.siemens.com/diagnostics Answers for life. Order No. A91DX-0701526-UC1-4A00 | Printed in USA | © 2009 Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc. Syva has been R1 R2 a leading developer N and manufacturer of AB R3 X N drugs-of-abuse tests R4 for more than 30 years. R2 C Now part of Siemens Healthcare ® Diagnostics, Syva boasts a long and Benzodiazepines have as their basic chemical structure successful track record in drugs-of-abuse a benzene ring fused to a seven-membered diazepine ring. testing, and leads the industry in the All important benzodiazepines contain a 5-aryl substituent ring (ring C) and a 1,4–diazepine ring. -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Deconstructing Tolerance with Clobazam Post Hoc Analyses from an Open-Label Extension Study

Deconstructing tolerance with clobazam Post hoc analyses from an open-label extension study Barry E. Gidal, PharmD ABSTRACT Robert T. Wechsler, MD, Objective: To evaluate potential development of tolerance to adjunctive clobazam in patients with PhD Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Raman Sankar, MD, PhD Methods: Eligible patients enrolled in open-label extension study OV-1004, which continued until Georgia D. Montouris, clobazam was commercially available in the United States or for a maximum of 2 years outside MD the United States. Enrolled patients started at 0.5 mg$kg21$d21 clobazam, not to exceed H. Steve White, PhD 40 mg/d. After 48 hours, dosages could be adjusted up to 2.0 mg$kg21$d21 (maximum 80 mg/d) James C. Cloyd, PharmD on the basis of efficacy and tolerability. Post hoc analyses evaluated mean dosages and drop- Mary Clare Kane, PhD seizure rates for the first 2 years of the open-label extension based on responder categories and Guangbin Peng, MS baseline seizure quartiles in OV-1012. Individual patient listings were reviewed for dosage David M. Tworek, MS, increases $40% and increasing seizure rates. MBA Vivienne Shen, MD, PhD Results: Data from 200 patients were included. For patients free of drop seizures, there was no Jouko Isojarvi, MD, PhD notable change in dosage over 24 months. For responder groups still exhibiting drop seizures, dosages were increased. Weekly drop-seizure rates for 100% and $75% responders demon- strated a consistent response over time. Few patients had a dosage increase $40% associated Correspondence to with an increase in seizure rates. Dr. Gidal: [email protected] Conclusions: Two-year findings suggest that the majority of patients do not develop tolerance to the antiseizure actions of clobazam. -

Drugs of Abuse: Benzodiazepines

Drugs of Abuse: Benzodiazepines What are Benzodiazepines? Benzodiazepines are central nervous system depressants that produce sedation, induce sleep, relieve anxiety and muscle spasms, and prevent seizures. What is their origin? Benzodiazepines are only legally available through prescription. Many abusers maintain their drug supply by getting prescriptions from several doctors, forging prescriptions, or buying them illicitly. Alprazolam and diazepam are the two most frequently encountered benzodiazepines on the illicit market. Benzodiazepines are What are common street names? depressants legally available Common street names include Benzos and Downers. through prescription. Abuse is associated with What do they look like? adolescents and young The most common benzodiazepines are the prescription drugs ® ® ® ® ® adults who take the drug Valium , Xanax , Halcion , Ativan , and Klonopin . Tolerance can orally or crush it up and develop, although at variable rates and to different degrees. short it to get high. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines used to manage insomnia include estazolam (ProSom®), flurazepam (Dalmane®), temazepam (Restoril®), Benzodiazepines slow down and triazolam (Halcion®). Midazolam (Versed®), a short-acting the central nervous system. benzodiazepine, is utilized for sedation, anxiety, and amnesia in critical Overdose effects include care settings and prior to anesthesia. It is available in the United States shallow respiration, clammy as an injectable preparation and as a syrup (primarily for pediatric skin, dilated pupils, weak patients). and rapid pulse, coma, and possible death. Benzodiazepines with a longer duration of action are utilized to treat insomnia in patients with daytime anxiety. These benzodiazepines include alprazolam (Xanax®), chlordiazepoxide (Librium®), clorazepate (Tranxene®), diazepam (Valium®), halazepam (Paxipam®), lorzepam (Ativan®), oxazepam (Serax®), prazepam (Centrax®), and quazepam (Doral®). -

Tranxene (Clorazepate Dipotassium)

Tranxene* T-TAB® Tablets (clorazepate dipotassium tablets, USP) Rx only DESCRIPTION Chemically, TRANXENE is a benzodiazepine. The empirical formula is C16H11ClK2N2O4; the molecular weight is 408.92; 1H-1, 4-Benzodiazepine-3-carboxylic acid, 7-chloro-2,3 dihydro-2-oxo-5-phenyl-, potassium salt compound with potassium hydroxide (1:1) and the structural formula may be represented as follows: The compound occurs as a fine, light yellow, practically odorless powder. It is insoluble in the common organic solvents, but very soluble in water. Aqueous solutions are unstable, clear, light yellow, and alkaline. TRANXENE T-TAB tablets contain either 3.75 mg, 7.5 mg or 15 mg of clorazepate dipotassium for oral administration. Inactive ingredients for TRANXENE T-TAB Tablets: Colloidal silicon dioxide, FD&C Blue No. 2 (3.75 mg only), FD&C Yellow No. 6 (7.5 mg only), FD&C Red No. 3 (15 mg only), magnesium oxide, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, potassium carbonate, potassium chloride, and talc. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacologically, clorazepate dipotassium has the characteristics of the benzodiazepines. It has depressant effects on the central nervous system. The primary metabolite, nordiazepam, quickly appears in the blood stream. The serum half-life is about 2 days. The drug is metabolized in the liver and excreted primarily in the urine. Studies in healthy men have shown that clorazepate dipotassium has depressant effects on the central nervous system. Prolonged administration of single daily doses as high as 120 mg was without toxic effects. Abrupt cessation of high doses was followed in some patients by nervousness, insomnia, irritability, diarrhea, muscle aches, or memory impairment. -

Stroke Rehabilitation

Medication Management for TBI Jun Zhang, MD, FAAPMR Assistant Professor Stony Brook University St. Charles Hospital “My brain? That's my second favorite organ.” Facts 1.8 million visits annually to the ED Over 289,000 patients were hospitalized annually for injuries related to a TBI. Where Is the Mango Princess Where Is the Mango Princess Cathy, Alan, and seven-year- old daughter Kelly from Philadelphia, won a raffle at Kelly’s school auction for a week long vacation at a remote location called Bob's Lake in Kingston, Ontario. Where Is the Mango Princess The vacation went pretty miserably, and on the last day they were ready to head home. Alan took a boat trip to take away dirty laundry and garbage from their cabin. On the way, a speedboat T-boned Alan's boat, knocking him in the head and causing massive bleeding and bruising. Kelly was in the boat and witnessed the accident. Where Is the Mango Princess The speedboat knocking him in the head and causing massive bleeding frontal lobe, TBI, DAI, or diffuse axonal injury Where Is the Mango Princess 44 YO left hand white male, with no significant PMH, s/p boat accident on July 1, 1996, with LOS then grand mal seizure, induced coma then intubated for airway protection. Airlifted to Kingston General Hospital for intensive care. Airlifted to the Hospital of the University of Philadelphia. Magee Rehabilitation Center. Day hospital Home. Where Is the Mango Princess Hyper-arousal/agitation What to do? First: environment change Second Medicine Beta-blockers Buspirone Psychotropic medications Benzodiazepines Amantadine Lamotrigine Beta Blocker Beta Blocker Benzodiazepines Benzodiazepines were first recognized in the 1950s for their ability to produce "taming" without apparent sedation in animal experiments. -

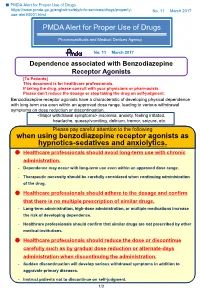

PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs When Using Benzodiazepine

■ PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/safety/info-services/drugs/properly- No. 11 March 2017 use-alert/0001.html PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency No. 11 March 2017 Dependence associated with Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists [To Patients] This document is for healthcare professionals. If taking the drug, please consult with your physicians or pharmacists. Please don’t reduce the dosage or stop taking the drug on self-judgment. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists have a characteristic of developing physical dependence with long-term use even within an approved dose range, leading to various withdrawal symptoms on dose reduction or discontinuation. <Major withdrawal symptoms> insomnia, anxiety, feeling irritated, headache, queasy/vomiting, delirium, tremor, seizure, etc. Please pay careful attention to the following when using benzodiazepine receptor agonists as hypnotics-sedatives and anxiolytics. Healthcare professionals should avoid long-term use with chronic administration. - Dependence may occur with long-term use even within an approved dose range. - Therapeutic necessity should be carefully considered when continuing administration of the drug. Healthcare professionals should adhere to the dosage and confirm that there is no multiple prescription of similar drugs. - Long-term administration, high-dose administration, or multiple medications increase the risk of developing dependence. - Healthcare professionals should confirm that similar drugs are not prescribed by other medical institutions. Healthcare professionals should reduce the dose or discontinue carefully such as by gradual dose reduction or alternate-days administration when discontinuing the administration. - Sudden discontinuation will develop serious withdrawal symptoms in addition to aggravate primary diseases. -

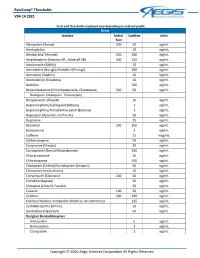

Paincomp® Thresholds V04.14.2021 Copyright © 2020 Aegis Sciences

PainComp® Thresholds V04.14.2021 Tests and thresholds employed vary depending on ordered profile Urine Analyte Initial Confirm Units Test Alprazolam (Xanax) 200 50 ng/mL Amitriptyline 10 ng/mL Amobarbital (Amytal) 200 200 ng/mL Amphetamine (Adzenys ER , Adderall XR) 500 250 ng/mL Aripiprazole (Abilify) 10 ng/mL Armodafinil (Nuvigil)/Modafinil (Provigil) 100 ng/mL Asenapine (Saphris) 10 ng/mL Atomoxetine (Strattera) 10 ng/mL Baclofen 500 ng/mL Benzodiazepines (Chlordiazepoxide, Clorazepate, 200 50 ng/mL Diazepam, Oxazepam, Temazepam) Brexpiprazole (Rexulti) 10 ng/mL Buprenorphine/Sublingual (Belbuca) 1 ng/mL Buprenorphine/Transdermal patch (Butrans) 1 ng/mL Bupropion (Aplenzin, Forfivo XL) 50 ng/mL Buspirone 25 ng/mL Butalbital 200 200 ng/mL Butorphanol 1 ng/mL Caffeine 15 mcg/mL Carbamazepine 50 ng/mL Cariprazine (Vraylar) 20 ng/mL Carisoprodol (Soma)/Meprobamate 200 ng/mL Chlorpromazine 10 ng/mL Chlorzoxazone 500 ng/mL Citalopram (Celexa)/Escitalopram (Lexapro) 50 ng/mL Clomipramine (Anafranil) 10 ng/mL Clonazepam (Klonopin) 200 50 ng/mL Clonidine (Kapvay) 50 ng/mL Clozapine (Clozaril, Fazaclo) 50 ng/mL Cocaine 100 50 ng/mL Codeine 200 100 ng/mL Cotinine/Nicotine metabolite (Habitrol, Nicoderm CQ) 125 ng/mL Cyclobenzaprine (Amrix) 10 ng/mL Dantrolene (Dantrium) 50 ng/mL Designer Benzodiazepines Adinazolam 5 ng/mL Bromazolam 1 ng/mL Clonazolam 1 ng/mL Copyright © 2020 Aegis Sciences Corporation All Rights Reserved PainComp® Thresholds V04.14.2021 Deschloroetizolam 1 ng/mL Diclazepam 1 ng/mL Etizolam 1 ng/mL Flualprazolam 1 ng/mL Flubromazepam -

Outpatient Detoxification of the Alcoholic

Outpatient Detoxification of the Alcoholic Gene J. Sausser, PhD, Skottowe B. Fishburne, Jr, MD, and V. Denise Everett Columbia, South Carolina Recent and proposed decreases in federal funding in support of publicly funded detoxification facilities and increased costs of inpatient detoxification will predictably lead to family physi cians being faced with the problem of alcohol detoxification for many of their patients. Outpatient detoxification is possible in the majority of cases, provided that good initial screening is accomplished and strong supportive resources exist. The ambulatory route is frequently not considered when ex amining mechanisms for the withdrawal of individuals from alcohol. The literature and experience indicate that, except in a small number of cases which can be adequately screened during the admission process, outpatient withdrawal can be an effective mechanism. Outpatient withdrawal must be consid ered not only by family physicians operating in the absence of alcohol support programs but also by alcohol treatment pro grams as a cost-effective alternative to many of the more ex pensive means of detoxifying alcoholic patients. In the face of increasing budgetary reductions at cost-effective and safe method of treatment. The all levels for the treatment of the alcoholic, outpa literature has documented successful treatment of tient detoxification must soon be considered as a the alcoholic on an outpatient basis if adequate support mechanisms and treatment regimens are employed. Successful inpatient detoxification of the alcoholic has been accomplished without use From the Department of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral of psychoactive medication. Science, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Three methods of detoxification have emerged, the Department of Psychiatry, William Bryan Dorn Veter ans Administration Hospital, and The William S. -

Clorazepate Dipotassium Tablets, USP)

Tranxene® T-TAB® Tablets (clorazepate dipotassium tablets, USP) Rx only Each tablet contains 7.5 mg of Clorazepate Dipotassium, USP equivalent to 5.8 mg of Clorazepate. WARNING: RISKS FROM CONCOMITANT USE WITH OPIOIDS Concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids may result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death (see WARNINGS, DRUG INTERACTIONS). • Reserve concomitant prescribing of these drugs for use in patients for whom alternative treatment options are inadequate. • Limit dosages and durations to the minimum required. • Follow patients for signs and symptoms of respiratory depression and sedation. DESCRIPTION Chemically, TRANXENE is a benzodiazepine. The empirical formula is C16H11ClK2N2O4; the molecular weight is 408.92; 1H-1, 4 Benzodiazepine-3-carboxylic acid, 7-chloro-2, 3-dihydro-2-oxo-5-phenyl-, potassium salt compound with potassium hydroxide (1:1) and the structural formula may be represented as follows:- The compound occurs as a fine, light yellow, practically odorless powder. It is insoluble in the common organic solvents, but very soluble in water. Aqueous solutions are unstable, clear, light yellow, and alkaline. Each tablet contains 7.5 mg of Clorazepate Dipotassium, USP equivalent to 5.8 mg of Clorazepate. Inactive ingredients for TRANXENE T-TAB Tablets: Colloidal silicon dioxide, FD&C Yellow No. 6, magnesium oxide, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, potassium carbonate, potassium chloride, and talc. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacologically, clorazepate dipotassium has the characteristics of the benzodiazepines. It has depressant effects on the central nervous system. The primary metabolite, nordiazepam, quickly appears in the blood stream. The serum half-life is about 2 days. The drug is metabolized in the liver and excreted primarily in the urine. -

PHARMACY TIMES by IEHP PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT February 11, 2013

PHARMACY TIMES BY IEHP PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT February 11, 2013 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed performance and quality measures to help Medicare beneficiaries make informed decisions regarding health and prescription drug plans. As part of this effort, CMS adopted measures for High Risk Medication (HRM) endorsed by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and the National Quality Forum (NQF). The HRM was developed using existing HEDIS measurement “Drugs to be avoided in the elderly”. The HRM rate analyzes the percentage of Medicare Part D beneficiaries 65 years or older who have received prescriptions for drugs with a high risk of serious side effects in the elderly. In order to advance patient safety, IEHP will be identifying members over 65 and currently on one of the medications identified in Table 1. Providers will be receiving a list of these members from IEHP on an ongoing basis. IEHP asks providers to review their member’s current drug regimen and safety risk and make any appropriate changes when applicable. Table 1: Medications identified by CMS to be high risk in the elderly: Drug Class Drug Safety Concerns IEHP Formulary Alternative(s) Acetylcholinesterase Donepezil (in patients Orthostatic hypotension or Memantine Inhibitor with syncope) bradycardia Amphetamines Dextroamphetamine CNS stimulation Weight Control: Diet Lisdextroamphetamine & lifestyle Diethylpropion modification Methylphenidate Phentermine Depression: mirtazapine, trazodone Analgesic Pentazocine Confusion, hallucination, Mild Pain: (includes Meperidine delirium, fall, fracture APAP combination Tramadol Lowers seizure threshold medications) Aspirin > 325 mg/day GI bleeding/peptic ulcer, edema Mod-Severe Pain Diflunisal may worsen heart failure Norco Etodolac Vicodin Fenoprofen Percocet Ketoprofen Morphine Meclofenamate Mefenamic acid Nabumetone 303 E. -

MEDICATION GUIDE Tranxene* (TRAN-Zeen) T-TAB (Clorazepate

MEDICATION GUIDE Tranxene* (TRAN-zeen) T-TAB® (clorazepate dipotassium) tablets Read this Medication Guide before you start taking TRANXENE and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your healthcare provider about your medical condition or treatment. What is the most important information I should know about TRANXENE? Do not stop taking TRANXENE without first talking to your healthcare provider. Stopping TRANXENE suddenly can cause serious problems. TRANXENE can cause serious side effects, including: 1. TRANXENE can make you sleepy or dizzy and can slow your thinking and motor skills • Do not drive, operate heavy machinery, or do other dangerous activities until you know how TRANXENE affects you. • Do not drink alcohol or take other drugs that may make you sleepy or dizzy while taking TRANXENE without first talking to your healthcare provider. When taken with alcohol or drugs that cause sleepiness or dizziness, TRANXENE may make your sleepiness or dizziness much worse. 2. TRANXENE can cause abuse and dependence. • Do not stop taking TRANXENE all of a sudden. Stopping TRANXENE suddenly can cause seizures that do not stop, hearing or seeing things that are not there (hallucinations), shaking, and stomach and muscle cramps. o Talk to your doctor about slowly stopping TRANXENE to avoid getting sick with withdrawal symptoms. o Physical dependence is not the same as drug addiction. Your healthcare provider can tell you more about the differences between physical dependence and drug addiction. TRANXENE is a federally controlled substance (C-IV) because it can be abused or lead to dependence.