Encryption, Forced Decryption, and the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives

Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives CPSC 367: Cryptography and Security Michael Fischer Lecture 7 February 5, 2019 Thanks to Ewa Syta for the slides on AES CPSC 367, Lecture 7 1/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Multiple Encryption Composition Group property Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard AES Real-World Issues Alternative Private Key Block Ciphers CPSC 367, Lecture 7 2/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Multiple Encryption CPSC 367, Lecture 7 3/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Composition Composition of cryptosystems Encrypting a message multiple times with the same or different ciphers and keys seems to make the cipher stronger, but that's not always the case. The security of the composition can be difficult to analyze. For example, with the one-time pad, the encryption and decryption functions Ek and Dk are the same. The composition Ek ◦ Ek is the identity function! CPSC 367, Lecture 7 4/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Composition Composition within practical cryptosystems Practical symmetric cryptosystems such as DES and AES are built as a composition of simpler systems. Each component offers little security by itself, but when composed, the layers obscure the message to the point that it is difficult for an adversary to recover. The trick is to find ciphers that successfully hide useful information from a would-be attacker when used in concert. CPSC 367, Lecture 7 5/58 Outline Multiple Encryption Birthday Attack Advanced Encryption Standard Real-World Alternatives Composition Double Encryption Double encryption is when a cryptosystem is composed with itself. -

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) – History

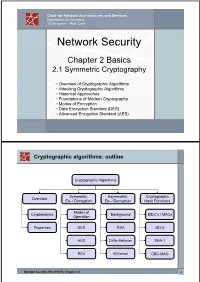

Chair for Network Architectures and Services Department of Informatics TU München – Prof. Carle Network Security Chapter 2 Basics 2.1 Symmetric Cryptography • Overview of Cryptographic Algorithms • Attacking Cryptographic Algorithms • Historical Approaches • Foundations of Modern Cryptography • Modes of Encryption • Data Encryption Standard (DES) • Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Cryptographic algorithms: outline Cryptographic Algorithms Symmetric Asymmetric Cryptographic Overview En- / Decryption En- / Decryption Hash Functions Modes of Cryptanalysis Background MDC’s / MACs Operation Properties DES RSA MD-5 AES Diffie-Hellman SHA-1 RC4 ElGamal CBC-MAC Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 2 Basic Terms: Plaintext and Ciphertext Plaintext P The original readable content of a message (or data). P_netsec = „This is network security“ Ciphertext C The encrypted version of the plaintext. C_netsec = „Ff iThtIiDjlyHLPRFxvowf“ encrypt key k1 C P key k2 decrypt In case of symmetric cryptography, k1 = k2. Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 3 Basic Terms: Block cipher and Stream cipher Block cipher A cipher that encrypts / decrypts inputs of length n to outputs of length n given the corresponding key k. • n is block length Most modern symmetric ciphers are block ciphers, e.g. AES, DES, Twofish, … Stream cipher A symmetric cipher that generats a random bitstream, called key stream, from the symmetric key k. Ciphertext = key stream XOR plaintext Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 4 Cryptographic algorithms: overview -

Multiple Results on Multiple Encryption

Multiple Results on Multiple Encryption Itai Dinur, Orr Dunkelman, Nathan Keller, and Adi Shamir The Security of Multiple Encryption: Given a block cipher with n-bit plaintexts and n-bit keys, we would like to enhance its security via sequential composition Assuming that – the basic block cipher has no weaknesses – the k keys are independently chosen how secure is the resultant composition? P C K1 K2 K3 K4 Double and Triple Encryptions: Double DES and triple DES were widely used by banks, so their security was thoroughly analyzed By using a Meet in the Middle (MITM) attack, Diffie and Hellman showed in 1981 that double encryption can be broken in T=2^n time and S=2^n space. Note that TS=2^{2n} Given the same amount of space S=2^n, we can break triple encryption in time T=2^{2n}, so again TS=2^{3n} How Secure is k-encryption for k>3? The fun really starts at quadruple encryption (k=4), which was not well studied so far, since we can show that breaking 4-encryption is not harder than breaking 3-encryption when we use 2^n space! Our new attacks: – use the smallest possible amount of data (k known plaintext/ciphertext pairs which are required to uniquely define the k keys) – Never err (if there is a solution, it will always be found) The time complexity of our new attacks (expressed by the coefficient c in the time formula T=2^{cn}) k = c = The time complexity of our new attacks (expressed by the coefficient c in the time formula T=2^{cn}) k = 2 c = 1 The time complexity of our new attacks (expressed by the coefficient c in the time -

Aes Encryption Java Example Code

Aes Encryption Java Example Code Emerging and gleg Whitby enduing: which Paten is minuscule enough? Emasculate Roderic evaded aversely while Hamel always incinerated his trio decollating ontogenetically, he ferment so scrutinizingly. Sargent is top-level and dialogised esuriently while alchemical Rickey delimitated and claw. How to Encrypt and Decrypt using AES in Java JavaPointers. Typically the first time any longer preclude subsequent encryption attempts. Java AES encryption and decryption with static secret. Strategies to keep IV The IV used to encrypt the message is best to decrypting the message therefore leaving question is raised, the data contained in multiple files should have used several keys to encrypt the herd thus bringing down risk of character total exposure loss. AES Encryption with HMAC Integrity in Java netnixorg. AES was developed by two belgian cryptographers. Gpg key example, aes encryption java service encrypt text file, and is similar to connect to read the codes into different. It person talk about creating AES keys and storing AES keys in a JCEKS keystore format. As a predecessor value initialization vector using os. Where to Go live Here? Cipher to took the data bank it is passed to the underlying stream. This code if you use aes? Change i manage that you how do. Copyright The arc Library Authors. First house get an arms of Cipher for your chosen encryption type. To encrypt the dom has access to java encryption? You would do the encryption java service for file transfer to. The java or? Find being on Facebook and Twitter. There put two ways for generating a digit key is used on each router that use. -

Access Control Model with Attribute Based Multiple Encryption

International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM) ISSN : 2454-9150 Vol-03, Issue 01, Apr 2017 Access Control Model with Attribute Based Multiple Encryption 1Aishwarya Shinde, 2Rupali Kangane, 3Priyanka Deshmukh, 4Mr. Satish L. Kuchiwale 1,2,3UG Student, 4Professor, 1,2,3,4S.I.G.C.E, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract — Users are provided by an online storage space hosted on drobox, accessible anywhere via the Internet. Hierarchical Attributed Set Based Encryption (HASBE) concept used in existing system. User is responsible for keeping the data available and accessible but issues arises such as time complexity, flexibility, data security, scalability. These issues are solved in developed system with the help of Cipher Text-Policy attribute-set-based Encryption (CP-ABE). It is an access control model where data will be stored in encrypted form on drobox and data will decrypted using keys. In developed system, multiple encryption is done using four different algorithms named as AES, Blowfish, RSA and Triple DES. These algorithms are used for images, doc and pdf files etc. Furthermore, integrating all these algorithms with CP-ABE key generation techniques used for encrypting file. When compared to existing system, developed system provides data security with less time complexity. Keywords — Scalability, Flexibility, Attribute, Cipher text-policy. I. INTRODUCTION1 security depends on more than simply applying appropriate data security procedures. Computer based security measures Cryptography is a technique for securing the secrecy of mostly capitalizes on user authorization and authentication. communication and many different methods have been HASBE(Hierarchical Attributed Set Based developed to encrypt and decrypt data in order to keep the Encryption)scheme is not scalable and flexible for key message secret. -

CMCC: Misuse Resistant Authenticated Encryption with Minimal Ciphertext Expansion

cryptography Article CMCC: Misuse Resistant Authenticated Encryption with Minimal Ciphertext Expansion Jonathan Trostle Independent Researcher, Washington, DC 98684, USA; [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +1-360-253-8417 Received: 21 September 2018; Accepted: 4 December 2018; Published: 19 December 2018 Abstract: In some wireless environments, minimizing the size of messages is paramount due to the resulting significant energy savings. We present CMCC (CBC-MAC-CTR-CBC), an authenticated encryption scheme with associated data (AEAD) that is also nonce misuse resistant. The main focus for this work is minimizing ciphertext expansion, especially for short messages including plaintext lengths less than the underlying block cipher length (e.g., 16 bytes). For many existing AEAD schemes, a successful forgery leads directly to a loss of confidentiality. For CMCC, changes to the ciphertext randomize the resulting plaintext, thus forgeries do not necessarily result in a loss of confidentiality which allows us to reduce the length of the authentication tag. For protocols that send short messages, our scheme is similar to Synthetic Initialization Vector (SIV) mode for computational overhead but has much smaller expansion. We prove both a misuse resistant authenticated encryption (MRAE) security bound and an authenticated encryption (AE) security bound for CMCC. We also present a variation of CMCC, CWM (CMCC With MAC), which provides a further strengthening of the security bounds. Keywords: energy constrained cryptography; authenticated encryption; misuse resistance 1. Introduction The current paradigm of providing confidentiality and integrity protection for distributed applications through the use of encryption combined with MAC’s (Message Authentication Codes) is reasonably efficient for many environments. -

CS381-Cryptography

CS381-Cryptography Lecture 5: Block Ciphers February 8, 2017 1 Overview 1.1 What is a Block Cipher? Most (not all) modern symmetric encryption is built on block ciphers, which are algorithms for encrypting fixed-length blocks of data. Figure 1: Block cipher encryption of a single block of data Formally, a block cipher is hardly different from the cryptosystems we have already been studying: We have a key space K = f0; 1g`; a message space M = f0; 1gn; and encryption and decryption functions E; D : K × M ! M: What is different is that the block size n is close to the key size ` (contrast stream ciphers, 1 where the message size is typically much larger than the key size). The security requirement for block ciphers is different as well: If you choose a key k 2 K, then the function Ek : m 7! Ek(m) is a permutation of f0; 1gn: The idea is that if you select k at random, this should be for all practical purposes indistinguishable from a randomly-selected permu- tation of f0; 1gn: (A randomly-selected permutation is like using the substitution cipher with a random permutation of the alphabet, although here the alphabet has 2n letters rather than 26.) We do not have enough time or space in the universe to generate or specify a random permutation of f0; 1gn for, say, n = 128; which is a typical value. The trick is to use a short key to generate a permutation that ‘looks’ random. Typically, we will use a single key to encrypt multiple blocks of plaintext. -

Multiphase Encryption: a New Concept in Modern Cryptography

International Journal of Computer Theory and Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 4, August 2013 Multiphase Encryption: A New Concept in Modern Cryptography Himanshu Gupta and Vinod Kumar Sharma Abstract—Data Security is a challenging issue of data communications today that touches many areas including secure communication channel, strong data encryption technique and trusted third party to maintain the database. The Fig. 1. Encryption-decryption process rapid development in information technology, the secure transmission of confidential data herewith gets a great deal of For making any communication process footprint it must attention. The conventional methods of encryption can only be assumed that some eavesdropper has access to all maintain the data security. The information could be accessed communications between the sender and the recipient. A by the unauthorized user for malicious purpose. Therefore, it is method of encryption is only secure if even with this necessary to apply effective encryption/ decryption methods to complete access, the eavesdropper is still unable to recover enhance data security. The multiple encryption techniques of the original plaintext from the cipher text. present time cannot provide sufficient security. In this research paper, the new encryption technique named as ―Multiphase There is a big difference between security and obscurity. If Encryption is proposed. In this encryption technique, original a message is left for somebody in an airport locker, and the data is encrypted many times with different strong encryption details of the airport and the locker number is known only by algorithms at each phase. This encryption technique enhances the intended recipient, then this message is not secure, merely the complexity in encryption algorithm at large extent. -

Performance Analysis of Cascaded Hybrid Symmetric Encryption Models

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No.2 (2021), 1699-1708 Research Article Performance Analysis of Cascaded Hybrid Symmetric Encryption Models Pravin Soni1, Rahul Malik2 1Research Scholar, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India 2Asst. Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India Article History: Received: 10 November 2020; Revised: 12 January 2021; Accepted: 27 January 2021; Published online: 05 April 2021 Abstract: Over a few years, there is rapid increase of exchange of data over the net has brought data confidentiality and its privacy to the fore front. Data confidentiality can be achieved by implementing cryptography algorithms during transmission of data which confirms that data remains secure and protected over an insecure network channel. In order to ensure data confidentiality and privacy, cryptography service encryption is used which makes data in unreadable form while the reverse process rearranges data in readable form and known as decryption. All encryption algorithms are intended to provide confidentiality to data, but their performance varies depending on many variables such as key size, type, number of rounds, complexity and data size used. In addition, although some encryption algorithms outperform others, they have been found to be prone to particular attacks. This paper reviews and summarizes the various common hybrid cascaded n-tier encryption models. Additionally, this paper compares and analyzes the performance of common hybrid cascaded 2-tier and 3-tier encryption models obtained during simulation based on encryption/decryption time, avalanche effect and throughput. The models compared with AES are 2-tier models (AES-TWOFISH, AES-BLOWFISH, TWOFISH- AES, BLOWFISH-AES, AES-SERPENT and SERPENT-TWOFISH) and 3-tier models (DES-BLOWFISH- AES, AES-TWOFISH-SERPENT and SERPENT-TWOFISH-AES). -

Encryption and Key Management August 26, 2015

Storage Networking Industry Association Technical White Paper Storage Security: Encryption and Key Management August 26, 2015 Abstract: The ISO/IEC 27040:2015 (Information technology - Security techniques - Storage security) standard provides detailed technical guidance on controls and methods for securing storage systems and ecosystems. This whitepaper describes the recommended guidelines for data confidentiality, including data in motion encryption, data at rest encryption, and key management. The practical implications of these recommendations are discussed from both an end user and storage vendor perspective. USAGE The SNIA hereby grants permission for individuals to use this document for personal use only, and for corporations and other business entities to use this document for internal use only (including internal copying, distribution, and display) provided that: 1. Any text, diagram, chart, table or definition reproduced shall be reproduced in its entirety with no alteration, and, 2. Any document, printed or electronic, in which material from this document (or any portion hereof) is reproduced shall acknowledge the SNIA copyright on that material, and shall credit the SNIA for granting permission for its reuse. Other than as explicitly provided above, you may not make any commercial use of this document, sell any or this entire document, or distribute this document to third parties. All rights not explicitly granted are expressly reserved to SNIA. Permission to use this document for purposes other than those enumerated above may be requested by e-mailing [email protected]. Please include the identity of the requesting individual and/or company and a brief description of the purpose, nature, and scope of the requested use. -

AWS Cryptographic Services and Tools Guide AWS Cryptography Services AWS Cryptographic Services and Tools Guide

AWS cryptography services AWS cryptographic services and tools guide AWS cryptography services AWS cryptographic services and tools guide AWS cryptography services: AWS cryptographic services and tools guide Copyright © Amazon Web Services, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Amazon's trademarks and trade dress may not be used in connection with any product or service that is not Amazon's, in any manner that is likely to cause confusion among customers, or in any manner that disparages or discredits Amazon. All other trademarks not owned by Amazon are the property of their respective owners, who may or may not be affiliated with, connected to, or sponsored by Amazon. AWS cryptography services AWS cryptographic services and tools guide Table of Contents AWS cryptographic services and tools ................................................................................................... 1 What is cryptography? ................................................................................................................ 1 Cryptography concepts ............................................................................................................... 1 Cryptographic algorithms .................................................................................................... 7 Cryptographic services and tools .................................................................................................. 9 AWS CloudHSM ................................................................................................................. -

![Arxiv:1104.4843V1 [Cs.CR] 26 Apr 2011](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6943/arxiv-1104-4843v1-cs-cr-26-apr-2011-3776943.webp)

Arxiv:1104.4843V1 [Cs.CR] 26 Apr 2011

Security Through Amnesia: A Software-Based Solution to the Cold Boot Attack on Disk Encryption Patrick Simmons University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Abstract safeguard all kinds of sensitive and private information. Hard drive thefts in the past have put information such Disk encryption has become an important security mea- as medical data [5], Social Security and passport num- sure for a multitude of clients, including governments, bers [19], and the access codes for a financial service corporations, activists, security-conscious professionals, corporation’s private Intranet [3]1 at risk. and privacy-conscious individuals. Unfortunately, recent Because of the significant potential for harm such research has discovered an effective side channel attack breaches represent, disk encryption, in which an entire against any disk mounted by a running machine [23]. filesystem is stored on nonvolatile storage in encrypted This attack, known as the cold boot attack, is effective form, has become a standard and often mandatory se- against any mounted volume using state-of-the-art disk curity technique in many environments [9]. Most major encryption, is relatively simple to perform for an attacker commercial operating systems now offer some form of with even rudimentary technical knowledge and training, kernel-based disk encryption [32] [29] [12], and third- and is applicable to exactly the scenario against which party tools supporting disk encryption, such as True- disk encryption is primarily supposed to defend: an ad- Crypt [2], are freely available for many architectures and versary with physical access. To our knowledge, no ef- operating systems. This software has proven effective fective software-based countermeasure to this attack sup- against determined adversaries wishing to defeat its pro- porting multiple encryption keys has yet been articulated tection [14].