Journal.Pone.0205646

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simulation of the Potential Impacts of Projected Climate Change on Streamflow in the Vakhsh River Basin in Central Asia Under CMIP5 RCP Scenarios

water Article Simulation of the Potential Impacts of Projected Climate Change on Streamflow in the Vakhsh River Basin in Central Asia under CMIP5 RCP Scenarios Aminjon Gulakhmadov 1,2,3,4 , Xi Chen 1,2,*, Nekruz Gulahmadov 1,3,5, Tie Liu 1 , Muhammad Naveed Anjum 6 and Muhammad Rizwan 5,7 1 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (T.L.) 2 Research Center for Ecology and Environment of Central Asia, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China 3 Institute of Water Problems, Hydropower and Ecology of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734042, Tajikistan 4 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734064, Tajikistan 5 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; [email protected] 6 Department of Land and Water Conservation Engineering, Faculty of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi, Rawalpindi 46000, Pakistan; [email protected] 7 Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Science, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-136-0992-3012 Received: 1 April 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020; Published: 17 May 2020 Abstract: Millions of people in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan are dependent on the freshwater supply of the Vakhsh River system. Sustainable management of the water resources of the Vakhsh River Basin (VRB) requires comprehensive assessment regarding future climate change and its implications for streamflow. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Strategic Framework for Free Economic Zones and Industrial Parks in the Kyrgyz Republic

Strategic Framework for Free Economic Zones and Industrial Parks in the Kyrgyz Republic Free economic zones that can be transformed into clusters of highly competitive traded firms can contribute significantly to industrial diversification and regional development of the Kyrgyz Republic. This strategic framework outlines strategies and policies for leveraging them to enhance productivity and promote regional development. The framework involves six pillars for integrating free economic zones and industrial parks: (i) using a sustainable development program with a mix of bottom–up and top–down approaches; (ii) enhancing the investment climate by ensuring the development of sound legal and regulatory frameworks, better institutional designs, and coordination; (iii) using a proactive approach with global value chains and upgrading along them by strengthening domestic capabilities; (iv) forming regional and cross-border value chains; (v) developing a sound implementation strategy; and (vi) establishing a sound monitoring and evaluation framework. About the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program The Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program is a partnership of 11 member countries and development partners working together to promote development through cooperation, leading to accelerated economic growth and poverty reduction. It is guided by the overarching vision of “Good Neighbors, Good Partners, and Good Prospects.” CAREC countries include: Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, the People’s Republic of China, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. ADB serves as the CAREC Secretariat. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. -

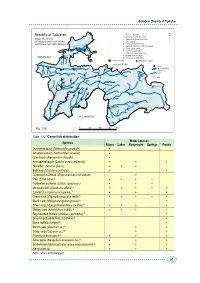

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

Biological Diversity of Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan The Legend: 1 - Acipenser nudiventris Lovet 2 - Salmo trutta morfa fario Linne ya 3 - A.a.a. (Linne) ar rd Sy 4 - Ctenopharyngodon idella Kayrakkum reservoir 5 - Hypophthalmichtus molitrix (Valenea) Khujand 6 - Silurus glanis Linne 7 - Cyprinus carpio Linne a r a 8 - Lucioperca lucioperea Linne f s Dagano-Say I 9 - Abramis brama (Linne) reservoir UZBEKISTAN 10 -Carassus auratus gibilio Katasay reservoir economical pond distribution location KYRGYZSTAN cities Zeravshan lakes and water reservoirs Yagnob rivers Muksu ob Iskanderkul Lake Surkh o CHINA b r Karakul Lake o S b gou o in h l z ik r b e a O b V y u k Dushanbe o ir K Rangul Lake o rv Shorkul Lake e P ch z a n e n a r j V ek em Nur gul Murg u az ab s Y h k a Y u ng Sarez Lake s l ta i r a u iz s B ir K Kulyab o T Kurgan-Tube n a g i n r Gunt i Yashilkul Lake f h a s K h Khorog k a Zorkul Lake V Turumtaikul Lake ra P a an d j kh Sha A AFGHANISTAN m u da rya nj a P Fig. 1.16. 0 50 100 150 Km Table 1.12. Game fish distribution Water sources Species Rivers Lakes Reservoirs Springs Ponds Dushanbe loach (Nemachilus pardalis) + Amudarya loach (Nemachilus oxianus) + Gray loach (Nemachilus dorsalis) + Aral spined loach (Cobitis aurata aralensis) + + + Sheatfish (Sclurus glanis) + + + Bullhead (Ictalurus punctata) А + + Turkestan bullhead (Glyptosternum reticulatum) + Pike (Esox lucius) + + + + Turkestan bullhead (Cottus spinolosus) + + + Mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) А + + + + + Zander (Lucioperca lucioperea) А + + + Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon della) А + + + + + Black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) А + Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthus molitrix) А + + + + Motley carp (Aristichthus nobilis) А + + + + Big-mouthed buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) А + Small-mouthed buffalo (I.bufalus) А + Black buffalo (I.niger) А + Mirror carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Scaly carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Pseudorasbora parva А + + + Amur goby (Neogobius amurensis sp.) А + + + Snakehead (Ophiocephalus argus warpachowski) А + + + Hemiculter sp. -

Industrial Development of Kyrgyzstan: Investment and Financing

Address: IIASA, Schlossplatz 1, A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria Email: [email protected] Department: Advanced Systems Analysis | ASA Working paper Industrial Development of Kyrgyzstan: Investment and Financing Nadejda Komendantova, Sergey Sizov, Uran Chekirbaev, Elena Rovenskaya, Nikita Strelkovskii, Nurshat Karabashov, Nurlan Atakanov, Zalyn Zheenaliev and Fernando Santiago Rodriguez WP-18-013 October 05, 2018 Approved by: Name: Albert van Jaarsveld Program: Director General and Chief Executive Officer Address: IIASA, Schlossplatz 1, A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria Email: [email protected] Department: Advanced Systems Analysis | ASA Table of contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Overview of investment climate ................................................................................. 4 2. Drivers and instruments for investment ...................................................................... 9 3. Barriers for investment ............................................................................................ 13 4. Socially and environmentally sustainable investment ................................................. 18 5. Key messages ......................................................................................................... 20 References ................................................................................................................. 22 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial -

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region 68 Central Asia Atlas of Natural Resources ater has long been the fundamental helped the region flourish; on the other, water, concern of Central Asia’s air, land, and biodiversity have been degraded. peoples. Few parts of the region are naturally water endowed, In this chapter, major river basins, inland seas, Wand it is unevenly distributed geographically. lakes, and reservoirs of Central Asia are presented. This scarcity has caused people to adapt in both The substantial economic and ecological benefits positive and negative ways. Vast power projects they provide are described, along with the threats and irrigation schemes have diverted most of facing them—and consequently the threats the water flow, transforming terrain, ecology, facing the economies and ecology of the country and even climate. On the one hand, powerful themselves—as a result of human activities. electrical grids and rich agricultural areas have The Amu Darya River in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan, with a canal (left) taking water to irrigate cotton fields.Upper right: Irrigation lifeline, Dostyk main canal in Makktaaral Rayon in South Kasakhstan Oblast, Kazakhstan. Lower right: The Charyn River in the Balkhash Lake basin, Kazakhstan. Water Resources 69 55°0'E 75°0'E 70 1:10 000 000 Central AsiaAtlas ofNaturalResources Major River Basins in Central Asia 200100 0 200 N Kilometers RUSSIAN FEDERATION 50°0'N Irty sh im 50°0'N Ish ASTANA N ura a b m Lake Zaisan E U r a KAZAKHSTAN l u s y r a S Lake Balkhash PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Ili OF CHINA Chui Aral Sea National capital 1 International boundary S y r D a r Rivers and canals y a River basins Lake Caspian Sea BISHKEK Issyk-Kul Amu Darya UZBEKISTAN Balkhash-Alakol 40°0'N ryn KYRGYZ Na Ob-Irtysh TASHKENT REPUBLIC Syr Darya 40°0'N Ural 1 Chui-Talas AZERBAIJAN 2 Zarafshan TURKMENISTAN 2 Boundaries are not necessarily authoritative. -

The Mineral Industry of Kyrgyzstan in 2015

2015 Minerals Yearbook KYRGYZSTAN [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior August 2019 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Kyrgyzstan By Karine M. Renaud Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked mountainous country with limited On April 23, 2014, the Parliament passed the “Glacier energy and transportation infrastructure. In 2014, gold remained Law,” which prohibits activities that cause damage to glaciers. the most valuable mineral mined in Kyrgyzstan. Other mineral Under the law, if glaciers are damaged, the companies who commodities produced in the country were clay, coal, fluorspar, are responsible are required to pay compensation at a rate gypsum, lime, mercury, natural gas, crude petroleum, sand and determined by the Government. Centerra Gold Inc. (Centerra) gravel, and silver (table 1; AZoMining, 2013; Gazprom PJSC, of Canada (the operator of the Kumtor Mine) could be affected 2015; Reichl and others, 2016). by the law because the Kumtor Mine bisects a glacier. The law remained to be signed by the Government before it takes effect, Minerals in the National Economy and no signing date had yet been specified (Lazenby, 2014; Marketwired, 2015). Kyrgyzstan’s real gross domestic product (GDP) increased by In 2015, the Russian Government approved a bill to create the 3.5% in 2015 compared with an increase of 4.0% (revised) in $1 billion Russian-Kyrgyz Development Fund. The Russian- 2014. The nominal GDP was $5.58 billion1 in 2015. Industrial Kyrgyz Development Fund is a lending program geared toward output decreased by 1.4% in 2015 compared with an increase the development of infrastructure, small- and medium-size of 5.7% in 2014, and it accounted for 15% of the GDP. -

The Geodynamics of the Pamir–Punjab Syntaxis V

ISSN 00168521, Geotectonics, 2013, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 31–51. © Pleiades Publishing, Inc., 2013. Original Russian Text © V.S. Burtman, 2013, published in Geotektonika, 2013, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 36–58. The Geodynamics of the Pamir–Punjab Syntaxis V. S. Burtman Geological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pyzhevskii per. 7, Moscow, 119017 Russia email: [email protected] Received December 19, 2011 Abstract—The collision of Hindustan with Eurasia in the Oligocene–early Miocene resulted in the rear rangement of the convective system in the upper mantle of the Pamir–Karakoram margin of the Eurasian Plate with subduction of the Hindustan continental lithosphere beneath this margin. The Pamir–Punjab syn taxis was formed in the Miocene as a giant horizontal extrusion (protrusion). Extensive nappes developed in the southern and central Pamirs along with deformation of its outer zone. The Pamir–Punjab syntaxis con tinued to form in the Pliocene–Quaternary when the deformed Pamirs, which propagated northward, were being transformed into a giant allochthon. A fold–nappe system was formed in the outer zone of the Pamirs at the front of this allochthon. A geodynamic model of syntaxis formation is proposed here. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852113010020 INTRODUCTION Mujan, BandiTurkestan, Andarab, and Albruz– The tectonic processes that occur in the Pamir– Mormul faults (Fig. 1). Punjab syntaxis of the Alpine–Himalayan Foldbelt The Pamir arc is more compressed as compared and at the boundary of this syntaxis with the Tien Shan with the Hindu Kush–Karakoram arc. Disharmony of have attracted the attention of researchers for many these arcs arose in the western part of the syntaxis due years [2, 7–9, 13, 15, 28]. -

The Amu Darya River – a Review

AMARTYA KUMAR BHATTACHARYA and D. M. P. KARTHIK The Amu Darya river – a review Introduction Source confluence Kerki he Amu Darya, also called the Amu river and elevation 326 m (1,070 ft) historically known by its Latin name, Oxus, is a major coordinates 37°06'35"N, 68°18'44"E T river in Central Asia. It is formed by the junction of the Mouth Aral sea Vakhsh and Panj rivers, at Qal`eh-ye Panjeh in Afghanistan, and flows from there north-westwards into the southern remnants location Amu Darya Delta, Uzbekistan of the Aral Sea. In ancient times, the river was regarded as the elevation 28 m (92 ft) boundary between Greater Iran and Turan. coordinates 44°06'30"N, 59°40'52"E In classical antiquity, the river was known as the Oxus in Length 2,620 km (1,628 mi) Latin and Oxos in Greek – a clear derivative of Vakhsh, the Basin 534,739 km 2 (206,464 sq m) name of the largest tributary of the river. In Sanskrit, the river Discharge is also referred to as Vakshu. The Avestan texts too refer to 3 the river as Yakhsha/Vakhsha (and Yakhsha Arta (“upper average 2,525 m /s (89,170 cu ft/s) Yakhsha”) referring to the Jaxartes/Syr Darya twin river to max 5,900 m 3 /s (208,357 cu ft/s) Amu Darya). The name Amu is said to have come from the min 420 m 3 /s (14,832 cu ft/s) medieval city of Amul, (later, Chahar Joy/Charjunow, and now known as Türkmenabat), in modern Turkmenistan, with Darya Description being the Persian word for “river”. -

Rapid Chromosomal Evolution in Enigmatic Mammal with XX in Both Sexes, the Alay Mole Vole Ellobius Alaicus Vorontsov Et Al., 1969 (Mammalia, Rodentia)

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogen 13(2):Rapid 147–177 chromosomal (2019) evolution in enigmatic mammal with XX in both sexes... 147 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v13i2.34224 DATA PAPER Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Rapid chromosomal evolution in enigmatic mammal with XX in both sexes, the Alay mole vole Ellobius alaicus Vorontsov et al., 1969 (Mammalia, Rodentia) Irina Bakloushinskaya1, Elena A. Lyapunova1, Abdusattor S. Saidov2, Svetlana A. Romanenko3,4, Patricia C.M. O’Brien5, Natalia A. Serdyukova3, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith5, Sergey Matveevsky6, Alexey S. Bogdanov1 1 Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 2 Pavlovsky Institu- te of Zoology and Parasitology, Academy of Sciences of Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe, Tajikistan 3 Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Siberian Branch RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia 4 Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, Russia 5 Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Department of Veterinary Me- dicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 6 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Corresponding author: Irina Bakloushinskaya ([email protected]) Academic editor: V. Lukhtanov | Received 1 March 2019 | Accepted 28 May 2019 | Published 20 June 2019 http://zoobank.org/4D72CDB3-20F3-4E24-96A9-72673C248856 Citation: Bakloushinskaya I, Lyapunova EA, Saidov AS, Romanenko SA, O’Brien PCM, Serdyukova NA, Ferguson- Smith MA, Matveevsky S, Bogdanov AS (2019) Rapid chromosomal evolution in enigmatic mammal with XX in both sexes, the Alay mole vole Ellobius alaicus Vorontsov et al., 1969 (Mammalia, Rodentia). Comparative Cytogenetics 13(2): 147–177. https://doi.org/10.3897/CompCytogen.v13i2.34224 Abstract Evolutionary history and taxonomic position for cryptic species may be clarified by using molecular and cy- togenetic methods. -

Water and Conflict in the Ferghana Valley: Historical Foundations of the Interstate Water Disputes Between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche Cattedra: Modern Political Atlas Water and Conflict in the Ferghana Valley: Historical Foundations of the Interstate Water Disputes Between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan RELATORE Prof. Riccardo Mario Cucciolla CANDIDATO Alessandro De Stasio Matr. 630942 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2017/2018 1 Sommario Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Water-Security Nexus and the Ferghana Valley ................................................................................. 9 1.1. Water and Conflict ................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1.1. Water uses ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.2. Water security and water scarcity ............................................................................................... 10 1.1.3. Water as a potential source of conflict ....................................................................................... 16 1.1.4. River disputes .............................................................................................................................. 25 1.2. The Ferghana Valley ............................................................................................................................ 30 1.2.1. Geography, hydrography, demography and -

Tajikistan Overview

1 Tajikistan Overview The Republic of Tajikistan is a landlocked and mountainous country located in Central Asia. It shares political boundaries with four other countries; Kyrgyzstan to the north, China to the east, Afghanistan to the south, and Uzbekistan to the west. Tajikistan remains the poorest and most economically fragile of the former Soviet Republics. More than half of its population lives on less than US$2 a day. Tajikistan’s Flag The Tajikistan flag is made up of three stripes of which the middle white stripe is the largest. The white is used to symbolize purity and cotton as well as the snowy mountain peaks of Tajikistan. The red color is to represent the sun, the strength and unity of the nation along with victory. Green is the color of Islam and a representation of the gift of nature. The central crown surrounded by seven stars has two meanings. The crown is used to represent the people of Tajikistan, the seven stars is to show happiness and perfection. 1 Courtesy of CIA World Factbook Physical Geography Tajikistan constitutes an area of 143,100 sq km, over 90 percent of which is mountainous.2 The Trans- Alay Mountains lie in the northern portion of the country and are joined with the rugged Pamir Mountains by the Alay Valley. Tajikistan’s highest point at 7,495 meters Qullai Ismoili Somoni, was previously known as “Communism Peak”, and was the tallest mountain in the former USSR. While the lowest elevation in the country is roughly 300 meters, fifty percent of the country is at an elevation of over 3,000 meters.3 Large valleys allowing for expansive agriculture periodically punctuate the mountains.