For Peer Review Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Management of Osteoporosis, April 2011 (Updated 04/2012, 06/2013, 09/2013, 04/2014, 09/2014 and 02/2015)

Hertfordshire Guidelines on Management of Osteoporosis, April 2011 (updated 04/2012, 06/2013, 09/2013, 04/2014, 09/2014 and 02/2015) Guidelines on Management of Osteoporosis Introduction These guidelines take into account recommendations from the DH Guidance on Falls and Fractures (Jul 2009), NICE Technology appraisals for Primary and Secondary Prevention (updated January 2011) and interpreted locally, National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) and local decisions on choice of drug treatment. The recommendations in the guideline should be used to aid management decisions but do not replace the need for clinical judgement in the care of individual patients in clinical practice. Diagnosis of osteoporosis The diagnosis of osteoporosis relies on the quantitative assessment of bone mineral density (BMD), usually by central dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). BMD at the femoral neck provides the reference site. It is defined as a value for BMD 2.5 SD or more below the young female adult mean (T-score less than or equal to –2.5 SD). Severe osteoporosis (established osteoporosis) describes osteoporosis in the presence of 1 or more fragility fracture. Diagnostic thresholds differ from intervention thresholds for several reasons. Firstly, the fracture risk varies at different ages, even with the same T-score. Other factors that determine intervention thresholds include the presence of clinical risk factors and the cost and benefits of treatment. Investigation of osteoporosis The range of tests will depend on the severity of the disease, age at presentation and the presence or absence of fractures. The aims of the clinical history, physical examination and clinical tests are to: • Exclude diseases that mimic osteoporosis (e.g. -

Alendronate, Etidronate, Risedronate, Raloxifene, Strontium Ranelate And

Issue date: October 2008 (amended January 2010 and January 2011) Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene, strontium ranelate and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women (amended) NICE technology appraisal guidance 161 (amended) NICE technology appraisal guidance 161 (amended) Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene, strontium ranelate and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women (amended) Ordering information You can download the following documents from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA161 • The NICE guidance (this document). • A quick reference guide – the recommendations. • ‘Understanding NICE guidance’ – a summary for patients and carers. • Details of all the evidence that was looked at and other background information. For printed copies of the quick reference guide or ‘Understanding NICE guidance’, phone NICE publications on 0845 003 7783 or email [email protected] and quote: • N1725 (quick reference guide) • N1726 (’Understanding NICE guidance’). This guidance represents the view of NICE, which was arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. Healthcare professionals are expected to take it fully into account when exercising their clinical judgement. However, the guidance does not override the individual responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or guardian or carer. Implementation of this guidance is the responsibility of local commissioners and/or providers. Commissioners and providers are reminded that it is their responsibility to implement the guidance, in their local context, in light of their duties to avoid unlawful discrimination and to have regard to promoting equality of opportunity. -

Botanicals in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis

nutrients Review Botanicals in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis Wojciech Słupski, Paulina Jawie ´nand Beata Nowak * Department of Pharmacology, Wroclaw Medical University, ul. J. Mikulicza-Radeckiego 2, 50-345 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] (W.S.); [email protected] (P.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-607-924-471 Abstract: Osteoporosis is a systemic bone disease characterized by reduced bone mass and the deterioration of bone microarchitecture leading to bone fragility and an increased risk of fractures. Conventional anti-osteoporotic pharmaceutics are effective in the treatment and prophylaxis of osteoporosis, however they are associated with various side effects that push many women into seeking botanicals as an alternative therapy. Traditional folk medicine is a rich source of bioactive compounds waiting for discovery and investigation that might be used in those patients, and therefore botanicals have recently received increasing attention. The aim of this review of literature is to present the comprehensive information about plant-derived compounds that might be used to maintain bone health in perimenopausal and postmenopausal females. Keywords: osteoporosis; menopause; botanicals; herbs 1. Introduction Women’s health and quality of life is modulated and affected strongly by hormone status. An oestrogen level that changes dramatically throughout life determines the Citation: Słupski, W.; Jawie´n,P.; development of women’s age-associated diseases. Age-associated hormonal imbalance Nowak, B. Botanicals in and oestrogen deficiency are involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases, e.g., obesity, Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. autoimmune disease and osteoporosis. Many female patients look for natural biological Nutrients 2021, 13, 1609. https:// products deeply rooted in folk medicine as an alternative to conventional pharmaceutics doi.org/10.3390/nu13051609 used as the prophylaxis of perimenopausal health disturbances. -

Nutriceuticals: Over-The-Counter Products and Osteoporosis

serum calcium levels are too low, and adequate calcium is not provided by the diet, calcium is taken from bone. Osteoporosis: Clinical Updates Long- term dietary calcium deficiency is a known risk Osteoporosis Clinical Updates is a publication of the National factor for osteo porosis. The recommended daily cal- Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF). Use and reproduction of this publication for educational purposes is permitted and cium intake from diet and supplements combined is encouraged without permission, with proper citation. This 1000 mg/day for people aged 19 to 50 and 1200 mg/ publication may not be used for commercial gain. NOF is a day for people older than 50. For all ages, the tolerable non-profit, 501(c)(3) educational organization. Suggested upper limit is 2500 mg calcium per day. citation: National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis Clinical Updates. Issue Title. Washington, DC; Year. Adequate calcium intake is necessary for attaining peak bone mass in early life (until about age 30) and for Please direct all inquiries to: National Osteoporosis slowing the rate of bone loss in later life.3 Although Foundation 1150 17th Street NW Washington, DC 20037, calcium alone (or with vitamin D) has not been shown USA Phone: 1 (202) 223-2226 to prevent estrogen-related bone loss, multiple stud- Fax: 1 (202) 223-1726 www.nof.org ies have found calcium consumption between 650 mg Statement of Educational Purpose and over 1400 mg/day reduces bone loss and increases Osteoporosis Clinical Updates is published to improve lumbar spine BMD.4-6 osteoporosis patient care by providing clinicians with state-of-the-art information and pragmatic strategies on How to take calcium supplements: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment that they may apply in Take calcium supplements with food. -

Strontium Ranelate Cochrane Reviews Does It Affect the Management of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis?

CLINICAL PRACTICE Strontium ranelate Cochrane reviews Does it affect the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis? This series of articles facilitated by the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group (CMSG) aims to place the findings of recent Tania Winzenberg Cochrane musculoskeletal reviews in a context immediately relevant to general practitioners. This article considers MBBS, FRACGP, whether the availability of strontium ranelate affects the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. MMedSc(ClinEpi), PhD, is Research Fellow – General Practice, Menzies Research Institute, University of Osteoporosis is a costly condition1,2 and is the fifth the pharmacologically active component of the compound Tasmania. tania.winzenberg@ most common musculoskeletal problem managed in and has been shown to simultaneously decrease bone utas.edu.au general practice at 0.9 per 100 patient encounters.3 resorption and stimulate bone formation both in vitro and in Sandi Powell Secondary prevention of osteoporotic fracture is poorly animal models,6 although the exact mechanisms for these MBBS(Hons), is junior implemented4 despite the availability of efficacious actions are as yet unclear. Research Fellow, Menzies Research Institute, and senior 1 treatments. O’Donnell et al performed a systematic review to assess endocrinology registrar, Royal the efficacy and adverse effects of strontium compared Hobart Hospital, Tasmania Strontium ranelate, a pharmacological treatment for to either placebo or other treatments for postmenopausal Graeme Jones osteoporosis which is relatively new to Australia, has been osteoporosis. The review results are summarised in Table MBBS(Hons), FRACP, MMedSc, available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) 1 and how these results might affect practice are shown MD, FAFPHM, is Head, by authority prescription since April 2007.5 Strontium is in Table 2. -

Pharmaco-Economic Study for the Prescribing of Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis

Technical Report 2: An analysis of the utilisation and expenditure of medicines dispensed for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis Technical report to NCAOP/HSE/DOHC By National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics An analysis of the utilisation and expenditure of medicines dispensed for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis February 2007 National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics Executive Summary 1. The number of prescriptions for the treatment and prophylaxis of osteoporosis has increased from 143,261 to 415,656 on the GMS scheme and from 52,452 to 136,547 on the DP scheme over the time period 2002 to 2005. 2. In 2005 over 60,000 patients received medications for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis on the GMS scheme with an associated expenditure of €16,093,676. 3. Approximately 80% of all patients who were dispensed drugs for the management of osteoporosis were prescribed either Alendronate (Fosamax once weekly) or Risedronate (Actonel once weekly) respectively. 4. On the DP scheme, over 27,000 patients received medications for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis in 2005 with an associated expenditure of € 6,028,925. 5. The majority of patients treated with drugs affecting bone structure were over 70 years e.g. 12,224 between 70 and 74yrs and 25,518 over 75yrs. 6. In relation to changes in treatment it was identified from the study that approximately 8% of all patients who are initiated on one treatment for osteoporosis are later switched to another therapy. 7. There was a statistically significant difference between the use of any osteoporosis medication and duration of prednisolone (dose response, chi- square test, p<0.0001). -

Recent Advances in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Osteoporosis

AGEING Clinical Medicine 2015 Vol 15, No 6: s92–s96 R e c e n t a d v a n c e s i n t h e p a t h o g e n e s i s a n d t r e a t m e n t of osteoporosis Authors: E l i z a b e t h M C u r t i s , A R e b e c c a J M o o n , B E l a i n e M D e n n i s o n , C N i c h o l a s C H a r v e y D a n d C y r u s C o o p e rE Over recent decades, the perception of osteoporosis has and propensity to fracture. Worldwide, there are nearly 9 changed from that of an inevitable consequence of ageing, to million osteoporotic fractures each year, and the US Surgeon that of a well characterised and treatable chronic non-commu- General's report of 2004, consistent with data from the UK, nicable disease, with major impacts on individuals, healthcare suggested that almost one in two women and one in five men systems and societies. Characterisation of its pathophysiol- will experience a fracture in their remaining lifetime from ABSTRACT ogy from the hierarchical structure of bone and the role of its the age of 50 years.1 The cost of osteoporotic fracture in the cell population, development of effective strategies for the UK approaches £3 billion annually and, across the EU, the identifi cation of those most appropriate for treatment, and estimated total economic cost of the approximately 3.5 million an increasing armamentarium of effi cacious pharmacologi- fragility fractures in 2010 was €37 billion. -

Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology Strontium Stimulates

Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 55 (2019) 15–19 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jtemb Technical note Strontium stimulates alkaline phosphatase and bone morphogenetic protein- 4 expression in rat chondrocytes cultured in vitro T Jinfeng Zhanga,b,1, Xiaoyan Zhua,1, Yezi Konga, Yan Huanga, Xukun Danga, Linshan Meia, ⁎ ⁎ Baoyu Zhaoa, Qing Lina,b, , Jianguo Wanga, a College of Veterinary Medicine, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China b State Key Laboratory of Plateau Ecology and Agriculture, Qinghai University, Xining 810016, Qinghai, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The trace element strontium has a significant impact on cartilage metabolism. However, the direct effects of Strontium strontium on alkaline phosphatase (ALP), a marker of bone growth, and bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP-4), Rat chondrocyte which plays a key role in the regulation of bone and cartilage development, are not entirely clear. In order to Expression understand the mechanisms involved in these processes, the chondrocytes were isolated from Wistar rat articular Alkaline phosphatase cartilage by enzymatic digestion and cultured under standard conditions. They were then treated with strontium Bone morphogenetic protein-4 at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 20.0 and 100.0 μg/mL for 72 h. The mRNA abundance and protein expression levels of ALP and BMP-4 were measured using real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR) and Western blot analysis. The results showed that the levels of expression of ALP and BMP-4 in chondrocytes increased as the con- centration of strontium increased relative to the control group, and the difference became significant at 1.0 μg/ mL strontium (P < 0.05). -

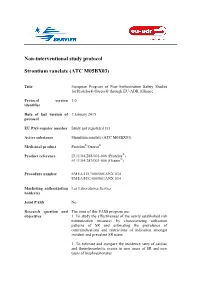

Non-Interventional Study Protocol Strontium Ranelate (ATC M05BX03)

Non-interventional study protocol Strontium ranelate (ATC M05BX03) Title European Program of Post-Authorization Safety Studies for Protelos®/Osseor® through EU-ADR Alliance Protocol version 3.0 identifier Date of last version of 7 January 2015 protocol EU PAS register number Study not registered yet Active substance Strontium ranelate (ATC M05BX03) Medicinal product Protelos®/Osseor® Product reference EU/1/04/288/001-006 (Protelos®) EU/1/04/287/001-006 (Osseor®) Procedure number EMEA/H/C/000560/ANX 034 EMEA/H/C/000561/ANX 034 Marketing authorization Les Laboratoires Servier holder(s) Joint PASS No Research question and The aims of this PASS program are: objectives 1. To study the effectiveness of the newly established risk minimization measures by characterizing utilization patterns of SR and estimating the prevalence of contraindications and restrictions of indication amongst incident and prevalent SR users 2. To estimate and compare the incidence rates of cardiac and thromboembolic events in new users of SR and new users of bisphosphonates Country(-ies) of study Denmark, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, and United Kingdom. Authors Dr. Daniel Prieto-Alhambra, MD MSc PhD Prof. Dr. Miriam CJM Sturkenboom, PharmD, PhD Marketing authorization holder(s) Marketing authorization Les Laboratoires Servier holder(s) 50 rue Carnot 92284 Suresnes cedex France MAH contact person Christine Bouillant Regulatory Affairs Department Manager Email: [email protected] Phone: +33.1.55.72.37.85 Fax: +33.1.55.72.50.44 07/01/15 2/78 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... 3 List of tables ............................................................................................................................... 5 List of figures ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ -

Pharmacological Advances in the Management of Osteoporosis

Clinical update Pharmacological advances in the management of osteoporosis Noel P Somasundaram1, M S A Cooray2 Sri Lanka Journal of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012; 2: 92-100 Abstract Osteoporosis is a worldwide health problem with a high prevalence. Agents for the treatment of osteoporosis are classified as antiresorptives, anabolic agents and drugs with combined anabolic and anti-resorptive actions. Although many drugs with proven efficacy are available for the treatment of osteoporosis their effectiveness has been limited by side-effects, concurrent comorbidities, and inadequate long-term compliance. Additionally, conventional antiresorptives such as aminobisphosphonates profoundly suppress bone resorption and formation which might contribute to the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Various novel antiresorptive agents are in development. This overview aims to discuss in brief some of the most promising novel treatments which include: bazedoxifene a new selective estrogen receptor modulator, denosumab, PTH rP (parathyroid hormone related protein), odanacatib and other bone anabolic agents such antibodies against sclerostin and dickkopf-1. Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) an anti-resorptive agent with a low side effect profile has been proven efficacious. Bazedoxifene has also proven its efficacy. Odanacatib, an inhibitor of cathepsin K, which is an osteoclast enzyme required for resorption of bone matrix is under assessment as an anti-resorptive -

Bisphosphonates for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis

TITLE: Denosumab and Zoledronic Acid for Patients with Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, Cost Effectiveness, and Guidelines DATE: 11 September 2012 CONTEXT AND POLICY ISSUES Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD), deterioration of bone microarchitecture, and a consequent increase in bone fragility and risk of fracture. 1 Osteoporosis is most prevalent in postmenopausal women over 50 as estrogen levels decline. 2,3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 10% of 60 year old women, 20% of 70 year old Women, and 40% of 80 year old women worldwide have osteoporosis. 2 In Canada, postmenopausal osteoporosis affects more than 1.5 million women. 4 BMD is determined by the delicate balance of bone resorption (osteoclast activity) and bone formation (osteoblast activity), with osteoporosis occurring when bone resorption exceeds bone formation. 3 There are several therapies available for the prevention and management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are highly potent inhibitors of osteoclastic bone resorption and have proven to be effective at reducing vertebral fracture risk. 5 Bisphosphonates such as alendronate and risedronate have been used for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis for many years and are taken orally with a daily dosage regimen. 5 Zoledronic acid (Aclasta) is a newer bisphosphonate administered intravenously once-yearly. 6 Recent advancements in the field of bone biology have led to the development of a new class of postmenopausal osteoporosis therapy. Denosumab (Prolia) is a human recombinant monoclonal antibody that binds to RANKL, a protein that acts as an essential mediator of osteoclast formation, thereby inhibiting osteoclast formation, function, and survival. -

Odanacatib, a Cathepsin K Inhibitor for the Treatment of Osteoporosis and Other Skeletal Disorders Associated with Excessive Bone Remodeling E Michael Lewiecki

!Drugs 200912(12):7~()-809 (~ Tliornso11 Reuters (Scientific) ltd ISSN 2040· 3410 DRUC PROFILE Odanacatib, a cathepsin K inhibitor for the treatment of osteoporosis and other skeletal disorders associated with excessive bone remodeling E Michael Lewiecki Address New Mexico Clinic.ii Research & Osteoporosis Center, 300 Oak Street NE, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA !:mail: lewiecki@aolcorn Odanacatib (MK·0822, MK-822) is an orally administered cathepsin K inhibitor being developed by Merck & Co Inc, under license from Ce/era Croup, for the treatment of osteoporosis and bone metastases. Cathepsin K, a lysosomol cysteine protease that is expressed by osteoclasts during the process of bone resorption, acts as the major col/agenase responsible for the degradation of the organic bone matrix during the bone remodeling process. Because excessive bone remodeling is a key element in the pathogenesis of postmenopousal osteoporosis and other skeletal disorders, cathepsin K is a potential target for therapeutic intervention. In a phase II clinical trial, weekly doses of odanacatib increased bone mineral density (BMD) and reduced bone turnover markers in postmenopausol women with low BMD. No tolerability concerns or evidence of skeletol toxicity were reported. Phase Ill trials, including a trial to evaluate the effects of odanocatib on froctt1re risk in up to 20,000 women with postmenopausol osteoporosis, were ongoing or recruiting participants at the time of publication. Odanacatib is a promising agent for the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis and other skeletal disorders associated with excessive bone remade/Ing. Introduction Therapeutic Odanacatib Osteoporosis is a common skeletal disease characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) and poor bone quality Originator Celera Group that reduces bone strength and increases the risk of fractures [506066].