Comparative Saturn-Versus-Jupiter Tether Operation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

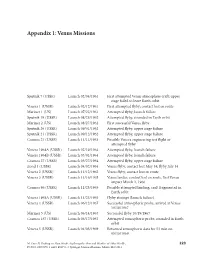

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

(Preprint) AAS 18-416 PRELIMINARY INTERPLANETARY MISSION

(Preprint) AAS 18-416 PRELIMINARY INTERPLANETARY MISSION DESIGN AND NAVIGATION FOR THE DRAGONFLY NEW FRONTIERS MISSION CONCEPT Christopher J. Scott,∗ Martin T. Ozimek,∗ Douglas S. Adams,y Ralph D. Lorenz,z Shyam Bhaskaran,x Rodica Ionasescu,{ Mark Jesick,{ and Frank E. Laipert{ Dragonfly is one of two mission concepts selected in December 2017 to advance into Phase A of NASA’s New Frontiers competition. Dragonfly would address the Ocean Worlds mis- sion theme by investigating Titan’s habitability and prebiotic chemistry and searching for evidence of chemical biosignatures of past (or extant) life. A rotorcraft lander, Dragonfly would capitalize on Titan’s dense atmosphere to enable mobility and sample materials from a variety of geologic settings. This paper describes Dragonfly’s baseline mission design giv- ing a complete picture of the inherent tradespace and outlines the design process from launch to atmospheric entry. INTRODUCTION Hosting the moons Titan and Enceladus, the Saturnian system contains at least two unique destinations that have been classified as ocean worlds. Titan, the second largest moon in the solar system behind Ganymede and the only planetary satellite with a significant atmosphere, is larger than the planet Mercury at 5,150 km (3,200 miles) in diameter. Its atmosphere, approximately 10 times the column mass of Earth’s, is composed of 95% nitrogen, 5% methane, 0.1% hydrogen along with trace amounts of organics.1 Titan’s atmosphere may resemble that of the Earth before biological processes began modifying its composition. Similar to the hydrological cycle on Earth, Titan’s methane evaporates into clouds, rains, and flows over the surface to fill lakes and seas, and subsequently evaporates back into the atmosphere. -

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN to BE HABITABLE? 8:15 A.M. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 A.M. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome C

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE HABITABLE? 8:15 a.m. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 a.m. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome Chair: Stephen Kane 8:30 a.m. Forget F. * Turbet M. Selsis F. Leconte J. Definition and Characterization of the Habitable Zone [#4057] We review the concept of habitable zone (HZ), why it is useful, and how to characterize it. The HZ could be nicknamed the “Hunting Zone” because its primary objective is now to help astronomers plan observations. This has interesting consequences. 9:00 a.m. Rushby A. J. Johnson M. Mills B. J. W. Watson A. J. Claire M. W. Long Term Planetary Habitability and the Carbonate-Silicate Cycle [#4026] We develop a coupled carbonate-silicate and stellar evolution model to investigate the effect of planet size on the operation of the long-term carbon cycle, and determine that larger planets are generally warmer for a given incident flux. 9:20 a.m. Dong C. F. * Huang Z. G. Jin M. Lingam M. Ma Y. J. Toth G. van der Holst B. Airapetian V. Cohen O. Gombosi T. Are “Habitable” Exoplanets Really Habitable? A Perspective from Atmospheric Loss [#4021] We will discuss the impact of exoplanetary space weather on the climate and habitability, which offers fresh insights concerning the habitability of exoplanets, especially those orbiting M-dwarfs, such as Proxima b and the TRAPPIST-1 system. 9:40 a.m. Fisher T. M. * Walker S. I. Desch S. J. Hartnett H. E. Glaser S. Limitations of Primary Productivity on “Aqua Planets:” Implications for Detectability [#4109] While ocean-covered planets have been considered a strong candidate for the search for life, the lack of surface weathering may lead to phosphorus scarcity and low primary productivity, making aqua planet biospheres difficult to detect. -

Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) View of Decadal Survey

Outer Solar System: Many Worlds to Explore Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) View of Decadal Survey Progress May 2017 Alfred McEwen, OPAG Chair LPL, University of Arizona This presentation will address (relevant to OPAG): • 1. Most important new discoveries 2011-2017 – (V&V writing was completed in late 2010) • 2. Progress made in implementing Decadal advice – Flight investigations • Flagship Missions • New Frontiers – R&A and infrastructure – Technology • 3. Other issues relevant to the committee’s statement of task – Smallsats for Outer Planet Exploration – How to make the Discovery Program useful for Outer Planets – Europa Lander – Coordination with ESA JUICE mission – Adding Ocean Worlds to New Frontiers 4 – Future mission studies to prepare for next Decadal • 4. Summary grade recommendations on Decadal progress • 5. OPAG top recommendations to mid-term review 1. Most Important New Discoveries 2011-present • Jupiter system: – Europa plate tectonics (Prockter et al., 2014) – Europa cryovolcanism (Quick et al., 2017; Prockter et al., 2017) – Europa plumes (Roth et al., 2014; Sparks et al., 2017) – Confirmation of subsurface ocean in Ganymede (Saur et al., 2015) – Evidence for extensive melt in Io’s mantle (Khurana et al., 2011; Tyler et al., 2015) – Fabulous results from Juno (papers submitted) • Saturn System: – MUCH from Cassini—see upcoming slides • Uranus and Neptune systems: – Standard interior models do not fit observations; Uranus and Neptune may be quite different (Nettelmann et al. 2013) – Intense auroras seen at Uranus (Lamy et al., 2012, 2017) – Weather on Uranus and Neptune confined to a “thin” layer (<1,000 km) (Kaspi et al. 2013) – Ice Giant growing around nearby TW Hydra (Rapson et al., 2015) – Triton’s tidal heating and possible subsurface ocean (Gaeman et al., 2012; Nimmo and Spencer, 2015) • Pluto system—lots of results from New Horizons – The Pluto system is complex in the variety of its landscapes, activity, and range of surface ages. -

No Slide Title

Planetary Protection Planetary Protection at NASA: Overview and Status Catharine A. Conley, NASA Planetary Protection Officer 1 May, 2012 2012 NASA Planetary Science Goals Planetary Protection Goal 2: Expand scientific understanding of the Earth and the universe in which we live. 2.3 Ascertain the content, origin, and evolution of the solar system and the potential for life elsewhere. 2.3.1 Inventory solar system objects and identify the processes active in and among them. 2.3.2 Improve understanding of how the Sun's family of planets, satellites, and minor bodies originated and evolved. 2.3.3 Improve understanding of the processes that determine the history and future of habitability of environments on Mars and other solar system bodies. 2.3.4 Improve understanding of the origin and evolution of Earth's life and biosphere to determine if there is or ever has been life elsewhere in the universe. 2.3.5 Identify and characterize small bodies and the properties of planetary environments that pose a threat to terrestrial life or exploration or provide potentially exploitable resources. NASA Planetary Protection Policy Planetary Protection • The policy and its implementation requirements are embodied in NPD 8020.7G (NASA Administrator) – Planetary Protection Officer acts on behalf of the Aassociate Administrator for Science to maintain and enforce the policy – NASA obtains recommendations on planetary protection issues (requirements for specific bodies and mission types) from the National Research Council’s Space Studies Board – Advice on -

The Science Case for a Titan Flagship-Class Orbiter with Probes (White Paper for the NRC Decadal Survey for Planetary Science and Astrobiology) Conor A

The Science Case for a Titan Flagship-class Orbiter with Probes (White paper for the NRC Decadal Survey for Planetary Science and Astrobiology) Conor A. Nixon, James Abshire, Andrew Ashton, Jason W. Barnes, Nathalie Carrasco, Mathieu Choukroun, Athena Coustenis, Louis-Alexandre Couston, Niklas Edberg, Alexander Gagnon, et al. To cite this version: Conor A. Nixon, James Abshire, Andrew Ashton, Jason W. Barnes, Nathalie Carrasco, et al.. The Science Case for a Titan Flagship-class Orbiter with Probes (White paper for the NRC Decadal Survey for Planetary Science and Astrobiology). 2020. hal-03085250 HAL Id: hal-03085250 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03085250 Preprint submitted on 21 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Science Case for a Titan Flagship-class Orbiter with Probes Authors: Conor A. Nixon, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA Planetary Systems Laboratory, 8800 Greenbelt Road, Greenbelt, MD 20771 (301) 286-6757 [email protected] James Abshire, University oF Maryland, USA Andrew Ashton, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, USA Jason W. Barnes, University oF Idaho, USA Nathalie Carrasco, Université Paris-Saclay, France, Mathieu Choukroun, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, USA Athena Coustenis, Paris Observatory, CNRS, PSL, France Louis-Alexandre Couston, British Antarctic Survey, UK Niklas Edberg, Swedish Institute oF Space Physics, Sweden Alexander Gagnon, University oF Washington, USA Jason D. -

Enceladus Explorer: Next Steps in the Development and Testing of a Steerable Subsurface Ice Probe for Autonomous Operation

Enceladus and the Icy Moons of Saturn (2016) 3031.pdf ENCELADUS EXPLORER: NEXT STEPS IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND TESTING OF A STEERABLE SUBSURFACE ICE PROBE FOR AUTONOMOUS OPERATION. B. Dachwald1, J. Kowalski2, F. Baader1, C. Espe1, M. Feldmann1, G. Francke1, E. Plescher1, 1Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, FH Aachen University of Applied Sciences, Hohenstaufenallee 6, 52064 Aa- chen, Germany, [email protected], 2Aachen Institute for Advanced Study in Computational Engineering Sci- ence, RWTH Aachen University, Germany Introduction: Direct access to subsurface liquid flexibly organized initiative with sub-projects focused material for in-situ analysis at Enceladus' South Polar on key research and development areas. The sub- Terrain is very difficult and requires advanced access project at FH Aachen is called EnEx-nExT (Environ- technology with a high level of cleanliness, robustness, mental Experimental Testing). Since the EnEx- and autonomy. A new technological approach has been IceMole was quite large (15 x 15 x 200 cm) and heavy developed as part of the collaborative research project / (60 kg), a much smaller (8 x 8 x 40 cm) and light- initiative “Enceladus Explorer” (EnEx) [1]. Within weight (< 5 kg) probe is currently developed within EnEx, the required technology for a potential Encela- EnEx-nExT. In the next two years, this smaller probe dus lander mission [2] is developed, evaluated, and will be tested in a vacuum chamber under simulated tested, with a strong focus on a steerable subsurface ice space conditions (pressure < 6 mbar, temperature probe. The EnEx probe shall autonomously navigate < 100 K) to prove the applicability of combined drill- through the ice and find a location where a liquid water ing and melting probes under more Enceladus-like sample can be taken and analyzed in situ. -

Titan Mare Explorer (TIME): the First Exploration of an Extraterrestrial Sea

Titan Mare Explorer (TIME): The First Exploration of an Extraterrestrial Sea Fact Sheet: Page 1 of 2 Science Objectives and Anticipated Payload . Determine the chemistry of a Titan lake to constrain Titan’s methane cycle. Instrument: Mass Spectrometer 1 . Determine the depth of a Titan lake. Instrument: Sonar 2 . Characterize physical properties of lake liquids. Instrument: Physical Properties Package 3a . Determine how the local meteorology over the lakes ties to the global cycling of methane. Instrument: Meteorology Package 3b . Analyze the morphology of lake surfaces, and if possible, shorelines, in order to constrain the kinetics of lake liquids and better understand the origin and evolution of Titan lakes. Instrument: Descent 4 and Surface 5 Imagers Focused, high-priority Discovery Science 5 Lake Lander Mission Objectives 3b . First exploration of planetary sea beyond Earth . Flight demonstration of ASRG in two Liquid environments: deep space and non- Level terrestrial atmosphere 4 . Pioneer low-cost, outer planet 1 missions 3a 2 Relevance and Importance to NASA Planetary Objectives and the Decadal Survey Decadal Survey – Volatiles and Organics, The Stuff of Life . Directly measure the organic constituents on another planetary object Decadal Survey – Processes: How Planetary Systems Work . First active measurement of liquid cycle beyond Earth Direct Successor to Revolutionary Cassini Discoveries Titan Mare Explorer (TIME): The First Exploration of an Extraterrestrial Sea Fact Sheet: Page 2 of 2 Major Mission Characteristics 1. Launch: 21 day window opens 17 January 2015 using an Atlas 411. 2. Cruise: One DSM, one Earth flyby en route to Saturn. 3. Titan Entry: Cruise stage separates from lander shortly before Titan entry on 29 June 2022. -

NASA Ames Research Center Intelligent Systems and High End Computing

NASA Ames Research Center Intelligent Systems and High End Computing Dr. Eugene Tu, Director NASA Ames Research Center Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000 A 80-year Journey 1960 Soviet Union United States Russia Japan ESA India 2020 Illustration by: Bryan Christie Design Updated: 2015 Protecting our Planet, Exploring the Universe Earth Heliophysics Planetary Astrophysics Launch missions such as JWST to Advance knowledge unravel the of Earth as a Determine the mysteries of the system to meet the content, origin, and universe, explore challenges of Understand the sun evolution of the how it began and environmental and its interactions solar system and evolved, and search change and to with Earth and the the potential for life for life on planets improve life on solar system. elsewhere around other stars earth “NASA Is With You When You Fly” Safe, Transition Efficient to Low- Growth in Carbon Global Propulsion Operations Innovation in Real-Time Commercial System- Supersonic Wide Aircraft Safety Assurance Assured Ultra-Efficient Autonomy for Commercial Aviation Vehicles Transformation NASA Centers and Installations Goddard Institute for Space Studies Plum Brook Glenn Research Station Independent Center Verification and Ames Validation Facility Research Center Goddard Space Flight Center Headquarters Jet Propulsion Wallops Laboratory Flight Facility Armstrong Flight Research Center Langley Research White Sands Center Test Facility Stennis Marshall Space Kennedy Johnson Space Space Michoud Flight Center Space Center Center Assembly Center Facility -

The Science Case for a Titan Flagship-Class Orbiter with Probes

The Science Case for a Titan Flagship-class Orbiter with Probes Authors: Conor A. Nixon, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA Planetary Systems Laboratory, 8800 Greenbelt Road, Greenbelt, MD 20771 (301) 286-6757 [email protected] James Abshire, University oF Maryland, USA Andrew Ashton, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, USA Jason W. Barnes, University oF Idaho, USA Nathalie Carrasco, Université Paris-Saclay, France, Mathieu Choukroun, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, USA Athena Coustenis, Paris Observatory, CNRS, PSL, France Louis-Alexandre Couston, British Antarctic Survey, UK Niklas Edberg, Swedish Institute oF Space Physics, Sweden Alexander Gagnon, University oF Washington, USA Jason D. Hofgartner, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, USA Luciano Iess, University oF Rome "La Sapienza", Italy Stéphane Le Mouélic, CNRS, University oF Nantes, France Rosaly Lopes, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, USA Juan Lora, Yale University, USA Ralph D. Lorenz, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, USA Adrienn Luspay-Kuti, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University USA, Michael Malaska, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, USA Kathleen Mandt, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, USA Marco Mastrogiuseppe, University oF Rome "La Sapienza", Italy Erwan Mazarico, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA Marc Neveu, University oF Maryland, USA Taylor Perron, Massachusetts Institute oF Technology, USA Jani Radebaugh, Brigham Young University, USA Sébastien Rodriguez, Université de Paris, IPGP, Diderot, France Farid Salama, NASA Ames Research Center, USA Ashley Schoenfeld, University oF CaliFornia Los Angeles, USA Jason M. Soderblom, Massachusetts Institute oF Technology, USA Anezina Solomonidou, European Space Agency/ESAC, Spain Darci Snowden, Central Washington University, USA Xioali Sun, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA Nicholas Teanby, School oF Earth Sciences, University oF Bristol, UK Gabriel Tobie, Université de Nantes, France Melissa G. -

The Lakes and Seas of Titan • Explore Related Articles • Search Keywords Alexander G

EA44CH04-Hayes ARI 17 May 2016 14:59 ANNUAL REVIEWS Further Click here to view this article's online features: • Download figures as PPT slides • Navigate linked references • Download citations The Lakes and Seas of Titan • Explore related articles • Search keywords Alexander G. Hayes Department of Astronomy and Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2016. 44:57–83 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on Cassini, Saturn, icy satellites, hydrology, hydrocarbons, climate April 27, 2016 The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences is Abstract online at earth.annualreviews.org Analogous to Earth’s water cycle, Titan’s methane-based hydrologic cycle This article’s doi: supports standing bodies of liquid and drives processes that result in common 10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012247 Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2016.44:57-83. Downloaded from annualreviews.org morphologic features including dunes, channels, lakes, and seas. Like lakes Access provided by University of Chicago Libraries on 03/07/17. For personal use only. Copyright c 2016 by Annual Reviews. on Earth and early Mars, Titan’s lakes and seas preserve a record of its All rights reserved climate and surface evolution. Unlike on Earth, the volume of liquid exposed on Titan’s surface is only a small fraction of the atmospheric reservoir. The volume and bulk composition of the seas can constrain the age and nature of atmospheric methane, as well as its interaction with surface reservoirs. Similarly, the morphology of lacustrine basins chronicles the history of the polar landscape over multiple temporal and spatial scales. -

Titan a Moon with an Atmosphere

TITAN A MOON WITH AN ATMOSPHERE Ashley Gilliam Earth 450 – Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn 4/29/13 SATURN HAS > 60 SATELLITES, WHY TITAN? Is the only satellite with a dense atmosphere Has a nitrogen-rich atmosphere resembles Earth’s Is the only world besides Earth with a liquid on its surface • Possible habitable world Based on its size… Titan " a planet in its o# $ght! R = 6371 km R = 2576 km R = 1737 km Ch$%iaan Huy&ns (1629-1695) DISCOVERY OF TITAN Around 1650, Huygens began building telescopes with his brother Constantijn On March 25, 1655 Huygens discovered Titan in an attempt to study Saturn’s rings Named the moon Saturni Luna (“Saturns Moon”) Not properly named until the mid-1800’s THE DISCOVERY OF TITAN’S ATMOSPHERE Not much more was learned about Titan until the early 20th century In 1903, Catalan astronomer José Comas Solà claimed to have observed limb darkening on Titan, which requires the presence of an atmosphere Gerard P. Kuiper (1905-1973) José Comas Solà (1868-1937) This was confirmed by Gerard Kuiper in 1944 Image Credit: Ralph Lorenz Voyager 1 Launched September 5, 1977 M"sions to Titan Pioneer 11 Launched April 6, 1973 Cassini-Huygens Images: NASA Launched October 15, 1997 Pioneer 11 Could not penetrate Titan’s Atmosphere! Image Credit: NASA Vo y a &r 1 Image Credit: NASA Vo y a &r 1 What did we learn about the Atmosphere? • Composition (N2, CH4, & H2) • Variation with latitude (homogeneously mixed) • Temperature profile Mesosphere • Pressure profile Stratosphere Troposphere Image Credit: Fulchignoni, et al., 2005 Image Credit: Conway et al.