'The Cutting Edge of Cocking About'1: Top Gear, Automobility And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

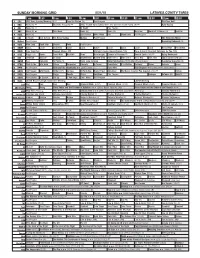

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

BBC Ultimately Successful in Russian “Top Gear” Trademark Saga

DE BERTI JACCHIA FRANCHINI FORLANI BBC ultimately successful in Russian “Top Gear” trademark saga 09/12/2019 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, RUSSIA Alisa Pestryakova of the assignment of the earlier mark and rademark “Top Gear” was registered registration of a new trademark by the T entrepreneur was to create an obstacle in Russia by the British Broadcasting to BBC’s mark. The British company Corporation (BBC) in 2015. Another asked the Court that its trademark “Top trademark “TopGear” owned by a Gear” should be maintained and also Russian company was registered in 2005 filed a cancellation application on non- for similar services, but the Russian PTO use basis against the earlier mark of the did not find grounds for refusal, and entrepreneur. The Court upheld the registered BBC’s mark. The mark cancellation decision of the Russian PTO “TopGear” owned by the Russian entity and held that neither the argument of was assigned to a Russian entrepreneur BBC on the abuse of right by the in 2016, who later also registered entrepreneur nor the cancellation of the another mark “TopGear” for the same earlier mark could affect the judgement. services in 2017. The details of the case were also described in the article “Battle for BBC Based on the application of the Top Gear trademark in Russia” published entrepreneur, the Russian PTO on Lexology on July 23, 2019. cancelled the “Top Gear” mark of BBC in (https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.a 2018 on the ground of the existence of a spx?g=14572e67-3758-4e95-8bce- similar mark with an earlier priority. -

Page 01 April 26.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Home | 5 Business | 19 Sport | 28 Travellers Gulf Warehousing Volleyball: Emir urged to take Co net profit Cup action precaution jumps 40 percent kicks off against malaria. in first quarter. from May 3. SUNDAY 26 APRIL 2015 • 7 Rajab 1436 • Volume 20 Number 6412 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Over 1,300 killed in Nepal quake Kathmandu landmarks destroyed; airport briefly closed; search on for survivors; thousands sleep in the open KATHMANDU: Tens of thou- Indian television. sands of people were spending Hospitals across the nation the night in the open under a Emir sends struggled to cope with the dead chilly and thunderous sky after and injured from Nepal’s worst a powerful earthquake devas- condolences quake in 81 years, and a lack of tated Nepal yesterday, killing equipment meant rescuers could more than 1,382 people, collaps- DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh look no deeper than surface rub- ing modern houses and ancient Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani ble for signs of life. temples and triggering a land- sent yesterday a cable of Areas of Kathmandu were slide on Mount Everest. Officials condolences to President of reduced to rubble, and rescue warned the death toll would rise Nepal Ram Baran Yadav operations had still not begun in as more reports came in from after an earthquake that hit some remote areas. Among the far-flung areas. Nepal yesterday. The Emir capital’s landmarks destroyed in Nepal urged countries to send expressed his deep condo- the earthquake was the 60-metre- aid to help it cope with the after- lences to the the families high (100-foot) Dharahara Tower, math as the desperate search for of the victims, wishing the built in 1832 for the queen of survivors continued into the early injured a swift recovery. -

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

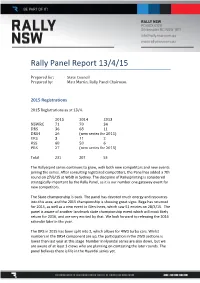

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

Dacia Sandero the Smarter Supermini This Is What an All-Rounder – Looks Like Dacia Sandero

Dacia Sandero The smarter supermini This is what an all-rounder – looks like Dacia Sandero 3 Dacia Sandero A little more about our range Dacia fully supports the introduction of the new emissions testing procedure, called ‘Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure’ (WLTP). WLTP represents a positive change to provide consumers with fuel economy and emissions data which is more representative of the results you may achieve in real life. 5 Be ready for anything Modern life is mad. One day you’re commuting in the city. Next day you’re packing up for a family adventure weekend. Luckily, the Sandero can keep up with your lifestyle like a champ. Its fluid lines, defined curves and honeycomb grille are proof that affordable doesn’t mean dull. While a choice of rigorously-tested engines and surprisingly robust suspension mean it’s equally inspiring behind the wheel. You can also relax with Hill Start Assist, ABS, Electronic Stability Control and front and side airbags, as standard. Everything you need for a smooth and peaceful ride. Fancy chilling out with air conditioning? Or rocking out to your favourite tunes on DAB or your phone using Bluetooth®, Apple CarPlay™ or Android Auto™*? It’s all possible with your Sandero. * Available on vehicles built from December 2018. Compatibility: An iPhone no earlier than iPhone 5 & iOS 7.1, an Anroid 5.0 (Lollipop). Connecting a smartphone to access Apple CarPlay™ or Android Auto™ should only be done when the car is safely parked. Drivers should only use the system when it is safe to do so and in compliance with the requirements of The Highway Code. -

Air Gear 28 Free

FREE AIR GEAR 28 PDF Oh! Great | 200 pages | 20 Jun 2013 | Kodansha America, Inc | 9781612620336 | English | New York, United States Air Gear 28 by Oh!Great: | : Books Meanwhile, the state of world politics grows erratic as the American president in the body of a teenage girl unveils the true scope of Air Treck technology. And what part do Ringo and Sleeping Forest have to play in all of this? When you buy a book, we donate a book. Sign in. Air Gear 28 By Oh! Great By Oh! Great Best Seller. Jun 18, ISBN Add to Cart. Also Air Gear 28 from:. Paperback —. Also in Air Gear. Also by Oh! Product Details. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Knights of Sidonia, Volume Tsutomu Nihei. Knights of Sidonia, Volume 6. Tsutsomu Nihei. Great Big Book Air Gear 28 Pencil Puzzles. Jacob Orleans. Eloquent JavaScript. Marijn Haverbeke. Raising the Stakes. The Satsuma Rebellion. Sean Michael Wilson. Shugo Chara Nexus Omnibus Volume 4. Star Trek: New Visions Volume 6. Alice E. KonigesTimothy G. Mattson and Yun Helen He. Pictures That Tick Volume 2. Eric Drooker. Sickness Unto Death, Part 2. Hikari Asada. New York Times. Nexus Omnibus Volume 7. Attack on Titan: Before the Fall Ryo Suzukaze. Showman Killer Vol. Alexandro Jodorowsky. Battle Angel Alita Mars Chronicle 2. Yukito Kishiro. Edwin Silberstang. Ruby Under a Microscope. Pat Shaughnessy. Star Trek: New Visions Volume 1. Geno Salvatore and R. The Massive Volume 5: Ragnarok. Nick Abadzis. Related Articles. Looking for Air Gear 28 Great Air Gear 28 Download Hi Res. LitFlash The eBooks you want at the lowest prices. -

Highlight Der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1

DMAX Programm Programmwoche 36, 01.09. bis 07.09.2012 Highlight der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1 (16) Am Montag, 10.09.2012 um 20:15 Uhr Wehe wenn sie losgelassen: In der neuen Staffel testen die Jungs von "Top Gear" die tollsten Luxuskarossen - manchmal geht´s jedoch auch mit dem Mähdrescher in den Schnee oder dem Hubschrauber aufs Autodach… Die spektakulärsten Autos der Welt, Testfahrten auf dem Vulkan und jede Menge coole Sprüche: DMAX holt "Top Gear" - die Mutter aller Auto-Shows - nach Hause. Das weltweit erfolgreichste TV-Format rund ums Thema „fahrbarer Untersatz“ begeistert seine Zuschauer seit Jahren mit sensationellen Stunts, präzise recherchierten Beiträgen und gefürchteten Kfz-Kritiken. Mehr Leidenschaft fürs Auto geht nicht! Darin ist sich die riesige Fan-Gemeinde des Kult-Formats rund um den Globus einig. Ganz zu schweigen vom bissigen britischen Humor der Moderatoren Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond und James May. Die ironischen Kommentare der Auto-Experten sind eben nicht zu toppen. Kurzum: Top Gear ist Kult! Know-how, Enthusiasmus und Faszination - die preisgekrönte BBC-Produktion hat mit DMAX in Deutschland die perfekte Heimat gefunden. "Als würde die Queen einen Tanga unterm Rock tragen!" - die Vergleiche, die Jeremy Clarkson in dieser Episode zieht, grenzen an Majestätsbeleidung. Doch der Top Gear-Experte ist vom schicken Interieur des Jaguar XJ so begeistert, dass er etwas über die Stränge schlägt. Da die luxuriöse V8- Raubkatze außerdem mächtig Dampf unterm Kessel hat, macht es Jeremy einen Riesenspaß auf der britischen Insel von Küste zu Küste zu brettern. Weitere Highlights dieser Episode: Porsche 959 und Ferrari F40 im Vergleich, sowie ein 3,5 Millionen Euro teuer NASA-Mondbuggy. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 179 4 April 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price) Channel 4, 7 December 2010, 22:00 5 [see page 37 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues)] Elite Days Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 12:00 to 13:15 Elite TV (Channel 965), 1 December 2010, 13:00 to 14:00 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 8 December 2010, 10.00 to 11:30 Elite Nights Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 22:30 to 23:35 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 6 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:25 Elite TV (Channel 965), 16 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:45 Elite TV (Channel 965), 22 December 2010, 00:50 to 01:20 Elite TV (Channel 965), 4 January 2011, 22:00 to 22:30 13 Page 3 Zing, 8 January 2011, 13:00 27 Deewar: Men of Power Star India Gold, 11 January 2011, 18:00 29 Bridezilla Wedding TV, 11 and 12 January 2011, 18:00 31 Resolved Dancing On Ice ITV1, 23 January 2011, 18:10 33 Not in Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues) Channel 4, 30 November 2010 to 29 December 2010, 22:00 37 [see page 5 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price)] Top Gear BBC2, 30 January 2011, 20:00 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Advertising Scheduling Cases In Breach Breach findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 47 Resolved Resolved findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 49 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Zac Goldsmith MP Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 15 and 16 July 2010 50 Other programmes not in breach 73 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes and licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on the BBC’s Impartiality, Accountability and Integrity BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University International Anglophone Media Studies Laura Kaai 3617602 Simon Cook January 2013 7,771 Words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Framework 4 2.1 The BBC’s Values 4 2.1.2 Impartiality 5 2.1.3 Conflicts of Interest 5 2.1.4 Past Controversy: The Russell Brand Show and the Carol Thatcher Row 6 2.1.5 The Clarkson Controversy 7 2.2 Columns 10 2.3 Media Discourse Analysis 12 2.3.2 Agenda Setting, Decoding, Fairness and Fallacy 13 2.3.3 Bias and Defamation 14 2.3.4 Myth and Stereotype 14 2.3.5 Sensationalism 14 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 15 3.1.2 Procedure 16 3.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 17 3.2.2 Procedure 19 4. Discussion 21 4.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 21 4.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 23 5. Conclusion 26 Works Cited 29 Appendices 35 3 1. Introduction “I’d have them all shot in front of their families” (“Jeremy Clarkson One”). This is part of the comment Jeremy Clarkson made on the 2011 public sector strikes in the UK, and the part that led to the BBC receiving 32,000 complaints. Clarkson said this during the 30 December 2011 live episode of The One Show, causing one of the biggest BBC controversies. The most widely watched factual TV programme in the world, with audiences in 212 territories worldwide, is BBC’s Top Gear (TopGear.com).