Jane Horrocks, Gracie Fields and Performing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 104 – July 2020

THE TIGER Homes for heroes by the sea . THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 104 – JULY 2020 CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to The Tiger. Whilst the first stage of the easing of the “lockdown” still prevent us from re-uniting at Branch Meetings, there is still a certain amount of good news emanating from the “War Front”. In Ypres, from 1st July, members of the public will be permitted to attend the Last Post Ceremony, although numbers will be limited to 152, with social distancing of 1.5 metres observed. 1st July will also see the re-opening of Talbot House in Poperinghe. Readers will be pleased to learn that the recent fund-raising appeal for the House, featured in this very column in the May edition of The Tiger reached its required target and my thanks go to those of you who donated to this worthy cause. Another piece of news has, as yet, received scant publicity but could prove to be the most important of all. In the aftermath of the recent “attack” on the Cenotaph, during which an attempt was made to set alight our national flag, I was delighted to read in the Press that: a Desecration of War Memorials Bill, carrying a ten year prison sentence, would be brought before the Commons as a matter of urgency. The subsequent discovery that ten years was the maximum sentence rather than the minimum tempered my joy somewhat, but the fact that War Memorials are now finally to be legally placed on a higher plane than other statuary is, at least in my opinion, a major step forward in their protection. -

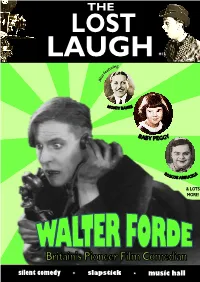

The Lost Laugh

#12 1 April 2020 Welcome to issue 12 of THE LOST LAUGH. I hope, wherever this reaches you, that you’re coping OK with these troubled times, and keeping safe and well. These old, funny films are a great form of escapism and light relief at times like these. In fact, I was thinking the other day that the times they were made in had their fair share of troubles : two world wars, the 1918 flu pandemic, the Wall Street Crash and the great depression, to name a few. Yet, these comics made people smile, often even making fun out of the anxi- eties of the day. That they can still make us smile through our own troubles, worlds away from their own, is testament to how special they are. I hope reading this issue helps you forget the outside world for a while and perhaps gives you some new ideas for films to seek out to pass some time in lockdown. Thanks to our contributors this issue: David Glass, David Wyatt and Ben Model; if you haven't seen them yet, Ben’s online silent comedy events are a terrific idea that help to keep the essence of live silent cinema alive. Ben has very kindly taken time to answer some questions about the shows. As always, please do get in touch at [email protected] with any comments or suggestions, or if you’d like to contribute an article (or plug a project of your own!) in a future issue. Finally, don’t for- get that there are more articles, including films to watch online, at thelostlaugh.com. -

Nine Night at the Trafalgar Studios

7 September 2018 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S PRODUCTION OF NINE NIGHT AT THE TRAFALGAR STUDIOS NINE NIGHT by Natasha Gordon Trafalgar Studios 1 December 2018 – 9 February 2019, Press night 6 December The National Theatre have today announced the full cast for Nine Night, Natasha Gordon’s critically acclaimed play which will transfer from the National Theatre to the Trafalgar Studios on 1 December 2018 (press night 6 December) in a co-production with Trafalgar Theatre Productions. Natasha Gordon will take the role of Lorraine in her debut play, for which she has recently been nominated for the Best Writer Award in The Stage newspaper’s ‘Debut Awards’. She is joined by Oliver Alvin-Wilson (Robert), Michelle Greenidge (Trudy), also nominated in the Stage Awards for Best West End Debut, Hattie Ladbury (Sophie), Rebekah Murrell (Anita) and Cecilia Noble (Aunt Maggie) who return to their celebrated NT roles, and Karl Collins (Uncle Vince) who completes the West End cast. Directed by Roy Alexander Weise (The Mountaintop), Nine Night is a touching and exuberantly funny exploration of the rituals of family. Gloria is gravely sick. When her time comes, the celebration begins; the traditional Jamaican Nine Night Wake. But for Gloria’s children and grandchildren, marking her death with a party that lasts over a week is a test. Nine rum-fuelled nights of music, food, storytelling and laughter – and an endless parade of mourners. The production is designed by Rajha Shakiry, with lighting design by Paule Constable, sound design by George Dennis, movement direction by Shelley Maxwell, company voice work and dialect coaching by Hazel Holder, and the Resident Director is Jade Lewis. -

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

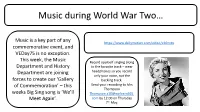

Ve Event, and Veday75 Is No Exception

Music during World War Two… Music is a key part of any https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x26nvcv commemorative event, and VEDay75 is no exception. This week, the Music Record yourself singing along Department and History to the karaoke track – wear Department are joining headphones so you record only your voice, not the forces to create our ‘Gallery backing track. of Commemoration’ – this Send your recording to Mrs Thompson weeks Big Sing song is ‘We’ll Thompson.s10@welearn365. Meet Again’. com by 12.00 on Thursday 7th May. Popular songs and singers of the 1930s/40s Vera Lynn – We’ll Meet Again Jonny Mercer – G I Jive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gh M_VmN6ytk BOlkHm-tM The Andrews Sisters – Boogie Vera Lynn – The White Cliffs of Woogie Bugle Boy Dover https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WA m1wuKvrxAw axkAgVkHQ Glenn Miller – Don’t sit under Flanagan and Allen – Run, Rabbit the apple tree Run https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AX https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw Oa3NCAuB4 czol6nIiQ Popular songs and singers of the 1930s/40s Judy Garland – Somewhere over the Al Bowlly – Goodnight Sweetheart Rainbow https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T https://www.youtube.com/watch?v WexuHVh9W8 =PSZxmZmBfnU George Formby – Bless ‘em all Gracie Fields – Wish me luck as you https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B wave me goodbye YGyAez5_MI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v =7EUytEX_XkE The Beverley Sisters – Roll out the Search for playlists on music streaming services barrel such as Spotify, e.g. -

The Singapore Grip Production Notes Low Res FINAL

THE SINGAPORE GRIP PRODUCTION NOTES Contents *** The content of this press pack is strictly embargoed until 0001hrs on Thursday 3 September *** Press Release 3-4 Interview with Jane Horrocks 29-31 Foreword by Sir Christopher Hampton 5 Interview with Charles Dance 33-35 Character Biographies 6-9 Interview with Colm Meaney 36-39 Interview with adaptor and executive producer Sir Christopher Hampton 10-12 Interview with Georgia Blizzard 40-43 Interview with producer Farah Abushwesha 13-16 Episodes One and Two Synopses 45-46 Interview with Luke Treadaway 17-20 Cast and Production Credits 50-52 Interview with David Morrissey 21-24 Publicity Contacts 53 Interview with Elizabeth Tan 25-28 2 Luke Treadaway, David Morrissey, Jane Horrocks, Colm Meaney and Charles Dance star in epic and ambitious adaptation of The Singapore Grip produced by Mammoth Screen Adapted from Booker Prize winner J.G. Farrell’s novel by Oscar winning screenwriter and playwright Sir Christopher Hampton (Atonement, Dangerous Liaisons), The Singapore grip stars Luke Treadaway, David Morrissey, Jane Horrocks, Colm Meaney and Charles Dance. Former Coronation Street actor Elizabeth Tan and rising star Georgia Blizzard will also star as leads in the highly anticipated series. An epic story set during World War Two, The Singapore Grip focuses on a British family living in Singapore at the time of the Japanese invasion. Olivier Award winning actor Luke Treadaway (The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Ordeal By Innocence, Traitors) plays the reluctant hero and innocent abroad Matthew Webb. Award winning actor, David Morrissey (The Missing, Britannia, The Walking Dead) takes the role of ruthless rubber merchant Walter Blackett, who is head of British Singapore’s oldest and most powerful firm alongside his business partner Webb played by Charles Dance OBE (Game of Thrones, And Then There Were None). -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

An Overview of the Working Classes in British Feature Film from the 1960S to the 1980S: from Class Consciousness to Marginalization

An Overview of the Working Classes in British Feature Film from the 1960s to the 1980s: From Class Consciousness to Marginalization Stephen C. Shafer University of Illinois Abstract The portrayal of the working classes has always been an element of British popular film from the comic music hall stereotypes in the era of Gracie Fields and George Formby in the 1930s to the more gritty realism of the “Angry Young Man” films that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. Curiously, in the last thirty years, the portrayal of the working classes in popular film has become somewhat less sharply drawn and more indistinct. In an odd way, these changes may parallel criticisms directed toward politicians about a declining sense of working-class unity and purpose in the wake of the Margaret Thatcher and post-Thatcher eras. When noted English film director and commentator Lindsay Anderson was asked to contribute an overview article on the British cinema for the 1984 edi- tion of the International Film Guide, he ruefully observed that from the per- spective of 1983 and, indeed, for most of its history, “British Cinema [has been] . a defeated rather than a triumphant cause.”1 Referring to the perennial fi- nancial crises and the smothering effect of Hollywood’s competition and influ- ence, Anderson lamented the inability of British films to find a consistent na- tional film tradition, adding that “the British Cinema has reflected only too clearly a nation lacking in energy and the valuable kind of pride . which cher- ishes its own traditions.”2 In particular, Anderson observed that when, on occa- sion, the British film industry had attempted to address the interests and needs of its working classes, the “aims” of the film-makers “were not supported . -

Film U Školi Vam Predstavlja Film DJEČAK U PRUGASTOJ PIDŽAMI

FUŠ – Film u školi Vam predstavlja film DJEČAK U PRUGASTOJ PIDŽAMI DJEČAK U PRUGASTOJ PIDŽAMI (The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas) Zemlja i godina proizvodnje: Velika Britanija, SAD, 2008. Trajanje filma: 94 min Žanr: drama, ratni Režija: Mark Herman Scenarij: Mark Herman po knjizi Johna Boynea Uloge: Asa Butterfield, Jack Scanlon, Vera Farmiga, David Thewlis, Rupert Friend, David Hayman,… Montaža: Michael Ellis Glazba: James Horner Zvuk: Peter Burgis, John Casali, Andie Derrick Kostimografija: Natalie Ward Šminka: Jacqueline Bhavnani, Hildegard Haide, Marese Langan,… Vizualni efekti: Louie Alexander, Simon Allmark, Ben Baker, Adrian Banton, Turea Blyth, Rouven Dombrowski,… Produkcija: Martin Childs, Tania Blunden, Daniel Hassid, István Király,… Producenti: Rosie Alison, Mark Herman, David Heyman, Christine Langan, Mary Richards Distribucija: Continental Najava filma: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBLKwOnpMX8 Prikladno za uzrast: IV. – VIII. Razred OŠ Korelacija s nastavnim predmetima: hrvatski jezik, engleski jezik, povijest, zemljopis, etika, vjeronauk, sat razrednog odjela Teme za raspravu: Drugi svjetski rat, antisemitizam, povijest, rat i život za vrijeme rata, holokaust, diskriminacija, kulturne vrijednosti i religijska različitost, prijateljstvo, hrabrost, humanost, adaptacija romana Festivali i nagrade: • British Independent Film Awards 2008., nagrada za najbolju glumicu (Vera Farmiga) • Chicago International Film Festival 2008., nagrada publike (Martin Herman) • CinEuphoria Awards 2010., Top 10, Nagrada za najbolji film (Herman), Nagrada za najbolju sporednu ulogu (Farmiga) • German Dubbing Awards 2010. i mnoge druge KRATAK SADRŽAJ Smještenu u vrijeme Drugog svjetskog rata, ovu filmsku priču (temeljenu na istoimenoj knjizi irskog autora Johna Boynea), gledamo nevinim očima osmogodišnjeg dječaka Brune, sina zapovjednika koncentracijskog logora, čije će zabranjeno prijateljstvo s dječakom Židovom, koji živi s druge strane ograde, rezultirati zapanjujućim i neočekivanim posljedicama.