Finding the Fourth Locale: Dichotomy Challenges in the Rhetoric of Barack Obama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the ACCORD As the “Saviours”, and Darfurians Negatively As Only Just the “Survivors”

CONTENTS EDITORIAL 2 by Vasu Gounden FEATURES 3 Paramilitary Groups and National Security: A Comparison Between Colombia and Sudan by Jerónimo Delgådo Caicedo 13 The Path to Economic and Political Emancipation in Sri Lanka by Muttukrishna Sarvananthan 23 Symbiosis of Peace and Development in Kashmir: An Imperative for Conflict Transformation by Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra 31 Conflict Induced Displacement: The Pandits of Kashmir by Seema Shekhawat 38 United Nations Presence in Haiti: Challenges of a Multidimensional Peacekeeping Mission by Eduarda Hamann 46 Resurgent Gorkhaland: Ethnic Identity and Autonomy by Anupma Kaushik BOOK 55 Saviours and Survivors: Darfur, Politics and the REVIEW War on Terror by Karanja Mbugua This special issue of Conflict Trends has sought to provide a platform for perspectives from the developing South. The idea emanates from ACCORD's mission to promote dialogue for the purpose of resolving conflicts and building peace. By introducing a few new contributors from Asia and Latin America, the editorial team endeavoured to foster a wider conversation on the way that conflict is evolving globally and to encourage dialogue among practitioners and academics beyond Africa. The contributions featured in this issue record unique, as well as common experiences, in conflict and conflict resolution. Finally, ACCORD would like to acknowledge the University of Uppsala's Department of Peace and Conflict Research (DPCR). Some of the contributors to this special issue are former participants in the department's Top-Level Seminars on Peace and Security, a Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) advanced international training programme. conflict trends I 1 EDITORIAL BY VASU GOUNDEN In the autumn of November 1989, a German continually construct walls in the name of security; colleague in Washington DC invited several of us walls that further divide us from each other so that we to an impromptu celebration to mark the collapse have even less opportunity to know, understand and of Germany’s Berlin Wall. -

De L'amour Différent

Document generated on 09/30/2021 6:07 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma De l’amour différent Maurice Elia Number 191, July–August 1997 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/49309ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Elia, M. (1997). De l’amour différent. Séquences, (191), 13–15. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1997 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ big fil M Bin, 6 T Eg Ci E li'AN DE CiMOUR DIFFÉRENT KEVIN SMITH Clerks (1994), Mallrats (1995), Chasing Amy (1997) arry Levinson, au début de sa carrière, avait fait de sa ville natale, ardemment s'en démarquer. En fait, il s'agit de quelques banlieues du centre Baltimore, un lieu fétiche: ce fut le site de quelques-uns de ses du New Jersey où Smith a grandi et où il continue de vivre et de travailler. Bgrands films (Diner, Tin Men, Avalon); en outre, il a créé la Bal Un autre lien entre ses trois films: les trois très-à-1'aise-dans-leur-sexua- timore Productions. -

Announcements February 28, 2020

Announcements February 28, 2020 Barack Hussein Obama II (/bəˈrɑːk huːˈseɪn oʊˈbɑːmə/ (About this soundlisten);[1] born August 4, 1961) is an American attorney and politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African-American president of the United States. He previously served as a U.S. senator from Illinois from 2005 to 2008 and an Illinois state senator from 1997 to 2004. Obama was born in Honolulu, Hawaii. After graduating from Columbia University in 1983, he worked as a community organizer in Chicago. In 1988, he enrolled in Harvard Law School, where he was the first black person to head the Harvard Law Review. After graduating, he became a civil rights attorney and an academic, teaching constitutional law at the University of Chicago Law School from 1992 to 2004. Turning to elective politics, he represented the 13th district from 1997 until 2004 in the Illinois Senate, when he ran for the U.S. Senate. Obama received national attention in 2004 with his March Senate-primary win, his well-received July Democratic National Convention keynote address, and his landslide November election to the Senate. In 2008, he was nominated for president a year after his presidential campaign began, and after close primary campaigns against Hillary Clinton. Obama was elected over Republican John McCain and was inaugurated on January 20, 2009. Nine months later, he was named the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize laureate. • Obama signed many landmark bills into law during his first two years in office. -

Quotes from Co-Signers of Garrett's Iran Letter to President

QUOTES FROM CO-SIGNERS OF GARRETT’S IRAN LETTER TO PRESIDENT BUSH Walter Jones ● Authored A Letter With Democrat Rep. Keith Ellison Encouraging Negotiations With Iran In 2012, Jones Signed A Letter With Democrat Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN) Encouraging Negotiations With Iran. “We strongly encourage your Administration to pursue bilateral and multilateral engagement with Iran. While we acknowledge that progress will be difficult, we believe that robust, sustained diplomacy is the best option to resolve our serious concerns about Iran's nuclear program, and to prevent a costly war that would be devastating for the United States and our allies in the region.” (Walter B. Jones and Keith Ellison, Letter, 3/2/12) ● Extreme Minority Of House Members To Vote Against Additional Sanctions On Iran In 2012, The House Passed Additional Sanctions Against Iran's Energy, Shipping, and Insurance Sectors. “Both houses of Congress approved legislation on Wednesday that would significantly tighten sanctions against Iran's energy, shipping and insurance sectors. The bill is the latest attempt by Congress to starve Iran of the hard currency it needs to fund what most members agree is Iran's ongoing attempt to develop a nuclear weapons program.” (Pete Kasperowicz, “House, Senate Approve Tougher Sanctions Against Iran, Syria,” The Hill's Floor Action, 8/1/12) One Of Only Six House Members To Vote Against The 2012 Sanctions Bill. “The sanctions bill was approved in the form of a resolution making changes to prior legislation, H.R. 1905, on which the House and Senate agreed — it passed in an 421-6 vote, and was opposed by just five Republicans and one Democrat. -

Giuliani, 9/11 and the 2008 Race

ABC NEWS/WASHINGTON POST POLL: ‘08 ELECTION UPDATE EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 11:35 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2007 Giuliani, 9/11 and the 2008 Race Six years after the terrorist attacks that vaulted him to national prominence, it’s unclear whether 9/11 will lift Rudy Giuliani all the way to the presidency: He remains hamstrung in the Republican base, and his overall support for his party’s nomination has slipped in the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll. Giuliani does better with Republicans who are concerned about another major terrorist attack in this country, a legacy of his 9/11 performance. But among those less focused on terrorism, he’s in a dead heat against newcomer Fred Thompson. Thompson also challenges Giuliani among conservatives and evangelical white Protestants – base groups in the Republican constituency – while John McCain has stabilized after a decline in support. Giuliani still leads, but his support is down by nine points in this poll from his level in July. Indeed this is the first ABC/Post poll this cycle in which Giuliani had less than a double- digit lead over all his competitors: He now leads Thompson by nine points (and McCain by 10). Among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, 28 percent support Giuliani, 19 percent Thompson, 18 percent McCain and 10 percent Mitt Romney. Other candidates remain in the low single digits. (There’s no significant difference among registered voters – and plenty of time to register.) ’08 Republican primary preferences Now July June April Feb Giuliani 28% 37 34 35 53 Thompson 19 15 13 10 NA McCain 18 16 20 22 23 Romney 10 8 10 10 5 The Democratic race, meanwhile, remains exceedingly stable; Hillary Clinton has led Barack Obama by 14 to 16 points in each ABC/Post poll since February, and still does. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations

REPORT ON THE LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORKS GUIDING THE UNITED STATES’ USE OF MILITARY FORCE AND RELATED NATIONAL SECURITY OPERATIONS December 2016 FOREWORD From President Lincoln’s issuance of the Lieber Code during the Civil War to our nation’s leadership at the Nuremberg Trials following World War II, the United States has a long history of emphasizing the development and enforcement of a framework under which war can be waged lawfully and effectively, with due regard for humanitarian considerations, and consistent with our national interests and values. Consistent with this long tradition, since my first days in office I have underscored the importance of adhering to standards—including international legal standards—that govern the use of force. Far from eroding our nation’s influence, I have argued, adherence to these standards strengthens us, just as it isolates those nations who do not follow such standards. Indeed, as I have consistently emphasized, what makes America truly remarkable is not the strength of our arms or our economy, but rather our founding values, which include respect for the rule of law and universal rights. Decisions regarding war and peace are among the most important any President faces. It is critical, therefore, that such decisions are made pursuant to a policy and legal framework that affords clear guidance internally, reduces the risk of an ill-considered decision, and enables the disclosure of as much information as possible to the public, consistent with national security and the proper functioning of the Government, so that an informed public can scrutinize our actions and hold us to account. -

Storm May Bring Snow to Valley Floor

Mendo women Rotarians plan ON THE MARKET fall to Solano Super Bowl bash Guide to local real estate .............Page A-6 ............Page A-3 ......................................Inside INSIDE Mendocino County’s Obituaries The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Rain High 45º Low 41º 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY Jan. 25, 2008 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 38 pages, Volume 149 Number 251 email: [email protected] Storm may bring snow to valley floor By ZACK SAMPSEL but with low pressure systems from and BEN BROWN Local agriculture not expected to sustain damage the Gulf of Alaska moving in one The Daily Journal after another the cycle remains the A second round of winter storms the valley floor, but the weather is not the county will experience scattered ing routine for some Mendocino same each day. lining up to hit Mendocino County expected to be a threat to agriculture. showers today with more mountain County residents. The previous low pressure system today is expected to bring more rain, According to reports from the snow to the north in higher eleva- Slight afternoon warmups have cold temperatures and snow as low as National Weather Service, most of tions, which has been the early-morn- helped to make midday travel easier, See STORM, Page A-12 GRACE HUDSON MUSEUM READIES NEW EXHIBIT Kucinich’s wife cancels planned stop in Hopland By ROB BURGESS The Daily Journal Hey, guess what? Kucinich quits Elizabeth Kucinich is coming to Mendocino campaign for County. Wait. Hold on. No, White House actually she isn’t. Associated In what should be a Press familiar tale to perennial- Democrat ly disappointed support- Dennis Kuci- ers of Democratic presi- nich is aban- dential aspirant Rep. -

Union Calendar No. 603

Union Calendar No. 603 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–930 ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS 2007–2008 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/ index.html http://www.house.gov/reform JANUARY 2, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed VerDate Aug 31 2005 01:57 Jan 03, 2009 Jkt 046108 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6012 Sfmt 6012 E:\HR\OC\HR930.XXX HR930 smartinez on PROD1PC64 with REPORTS congress.#13 ACTIVITIES REPORT OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM VerDate Aug 31 2005 01:57 Jan 03, 2009 Jkt 046108 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 E:\HR\OC\HR930.XXX HR930 smartinez on PROD1PC64 with REPORTS with PROD1PC64 on smartinez 1 Union Calendar No. 603 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–930 ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS 2007–2008 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/ index.html http://www.house.gov/reform JANUARY 2, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 46–108 WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Aug 31 2005 01:57 Jan 03, 2009 Jkt 046108 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR930.XXX HR930 smartinez on PROD1PC64 with REPORTS congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HENRY A. -

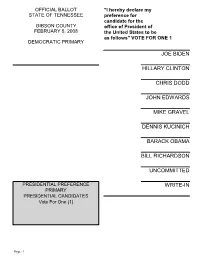

Joe Biden Hillary Clinton Chris Dodd John Edwards Mike Gravel Dennis Kucinich Barack Obama Bill Richardson Uncommitted Write-In

OFFICIAL BALLOT "I hereby declare my STATE OF TENNESSEE preference for candidate for the GIBSON COUNTY office of President of FEBRUARY 5, 2008 the United States to be as follows" VOTE FOR ONE 1 DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY JOE BIDEN HILLARY CLINTON CHRIS DODD JOHN EDWARDS MIKE GRAVEL DENNIS KUCINICH BARACK OBAMA BILL RICHARDSON UNCOMMITTED PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE WRITE-IN PRIMARY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Vote For One (1) Page: 1 PROPERTY ASSESSOR Vote For One (1) MARK CARLTON JOSEPH F. HAMMONDS JOHN MCCURDY GARY F. PASCHALL WRITE-IN Page: 2 OFFICIAL BALLOT "I hereby declare my STATE OF TENNESSEE preference for candidate for the GIBSON COUNTY office of President of FEBRUARY 5, 2008 the United States to be as follows" VOTE FOR ONE 1 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY RUDY GIULIANI MIKE HUCKABEE DUNCAN HUNTER ALAN KEYES JOHN MCCAIN RON PAUL MITT ROMNEY TOM TANCREDO FRED THOMPSON PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE UNCOMMITTED PRIMARY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Vote For One (1) WRITE-IN Page: 3 THE FOLLOWING OFFICE Edna Elaine Saltsman CONTINUES ON PAGES 2-5 John Bruce Saltsman, Sr. DELEGATES AT LARGE John "Chip" Saltsman, Jr. Committed and Uncommitted Vote For Twelve (12) Kari H. Smith MIKE HUCKABEE Michael L. Smith Emily G. Beaty Windy J. Smith Robert Arthur Bennett JOHN MCCAIN H.E. Bittle III Todd Gardenhire Beth G. Cox Justin D. Pitt Kenny D. Crenshaw Melissa B. Crenshaw Dan L. Hardin Cynthia H. Murphy Deana Persson Eric Ratcliff CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE Page: 4 DELEGATES AT LARGE Matthew Rideout Committed and Uncommitted Vote For Twelve (12) Mahmood (Michael) Sabri RON PAUL Cheryl Scott William M. Coats Joanna C. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1873

March 23, 2010 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1873 report of a rule entitled ‘‘Federal Acquisi- ant to law, a report relative to the acquisi- forty-fourth President of the United States tion Regulation; FAR Case 2008–006, En- tions made annually from entities that man- of America, Barack Obama, the Nobel Peace hanced Competition for Task- and Delivery- ufacture articles, materials, or supplies out- Prize for his ‘‘extraordinary efforts to Order Contracts—Section 843 of the Fiscal side of the United States for fiscal year 2009; strengthen international diplomacy and co- Year 2008 National Defense Authorization to the Committee on Homeland Security and operation between peoples’’; and Governmental Affairs. Act’’ (RIN9000–AL05) received in the Office of WHEREAS, it is important for commu- EC–5180. A communication from the Sec- nities throughout the Nation to recognize the President of the Senate on March 22, retary of Transportation, transmitting draft this momentous occasion; 2010; to the Committee on Homeland Secu- legislation to provide authority to com- NOW, THEREFORE, IT IS HEREBY RE- rity and Governmental Affairs. pensate Federal employees for the two-day SOLVED BY THE CITY COMMISSION OF EC–5171. A communication from the Acting period in which authority to make expendi- THE CITY OF LAUDERHILL, FLORIDA: Senior Procurement Executive, Office of Ac- tures from the Highway Trust Fund lapsed, SECTION 1: Each ‘‘WHEREAS’’ clause set quisition Policy, General Services Adminis- and for other purposes; to the Committee on forth above is true and correct and is incor- tration, transmitting, pursuant to law, the Homeland Security and Governmental Af- porated herein. -

MEET the CITY COUNCIL CANDIDATES...Page 2

MEET THE CITY COUNCIL CANDIDATES....Page 2 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 2020 VOLUME 14 NO. 39 THE BELOVED SIERRA MADREAN, BUD LIBRARY TRUSTEES PUSH FOR WEBB-MARTIN GROUP SWITZER, PASSES AWAY REPAIRS/NEW FACILITY The Sierra Madre Library Board of Trustees met with the City Council Around Sierra Madre to discuss the future of the library including needed updates and repairs, use of the adjacent lot and the chance of putting the construction of a new building on the ballot in either 2022 or 2024. As of today, a parcel tax to replace the current library does not have the necessary votes to make it on the 2020 ballot, according to a survey conducted by FM3 Research. Approximately 55% of those surveyed said they would vote “yes” on a ballot measure, which is well below the two- thirds needed for passage. Fifty-three percent of Sierra Madre residents, who were surveyed back We are with the families affected by in 2018, were in favor of making needed repairs to the current library the fires and we thank our firemen with only 33% in favor of the construction of a new library. City Council for their bravery and protection. members expressed concern over spending funds on repairs to a building that could be replaced by a new facility if such a project was approved on a ballot in the next four years. The City is already dealing with added expenditures as a result of COVID-19 and the Bobcat Fire. Estimates for It is our sad duty to report that Glidden "Bud" Switzer peacefully passed repair to the library and adjacent lot range from $800,000 to $3.5 million, away on September 23rd, shortly after his 92nd birthday.