Is Scientology a Religion?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bearable Freedom. Exploring the Becoming of the Artist in Education, Work and Family Life

Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 692 (Un)bearable freedom. Exploring the becoming of the artist in education, work and family life. Sofia Lindström Department of Culture Studies Faculty of Arts and Sciences Linköping University, SE-601 74 Norrköping, Sweden Norrköping 2016 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 692 At the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in arts and Science. This thesis comes from the Department of Cultural Studies (Tema Kultur och Samhälle, Tema Q) At Tema Q, culture is studied as a dynamic field of practices, including agency as well as structure, and cultural products as well as the way they are produced, consumed, communicated and used. Tema Q is part of the larger Department for Studies of Social Change and Culture (ISAK). Distributed by: Department of Culture Studies (Tema Q) Linköping University 601 74 Norrköping Sofia Lindström (Un)bearable freedom - Exploring the becoming of the artist in education, work and family life Edition 1:1 ISBN 978-91-7685-717-5 ISSN 0282-9800 ©Sofia Lindström Department of Culture Studies, ISAK 2016 Printed by: LiU Tryck 2 Abstract The aim of this dissertation is to explore and understand three important social contexts for the construction of an artistic subjectivity: education, work and family life. The empirical data consist of interview material with alumni from the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, staff of the institute, and a survey material from the Swedish National Artist’s Organization (KRO/KIF). -

By L. Ron Hubbard Dianetics and Scientology May Be a Century Ahead of Their Times but Still They Are Just in Time Before We All Go up in Smoke

THE AUDITORI! THE MONTHLY JOURNAL OF SCIENTOLOGY DIANETICS by L. Ron Hubbard Dianetics and Scientology may be a century ahead of their times but still they are just in time before we all go up in smoke DIANETICS means “through the mind” (Greek: THE “REACTIVE MIND” DISCOVERED was never really applied to the mind. “Dia” — through, “noos” - mind]. In early Dianetic research the human mind and “Researchers” in this field were not fully It is the first fully precise science of the mind. basic human- character were found to have been trained in mathematics, the scientific method or The world before Dianetics had never known a most grossly maligned because Man had not been logic. They were interested mainly in their own precision mental Science. able to distinguish between irrational conduct private ideas and in political targets. derived from another, far more vicious source. Dianetics was first conceived in 1930. A long Man has used mental knowledge in the past research in ancient and modern philosophy The Reactive Mind was discovered. It had man mainly for control, politics and propaganda. culminated in 1938 when I discovered that the aged to bury itself from view so thoroughly that OTHER “MENTAL THERAPY" common denominator of all existence was only inductive philosophy, travelling from effect SURVIVE. back to cause, served to uncpyer it. The Reactive Various forms of “mental therapy” were in ex Dianetics was first publicly released in 1950 Mind is a portion of a person’s mind which works istence before Dianetics. I with the book Dianetics, the Modem Science of on a totally stimulus-response basis, which is not Psychology and psychiatry were developed Mental Health/ and has been increasingly success under his volitional control, and which exerts force chiefly by a Russian veterinarian named Ivan Petro ful since that time. -

The Dangerous Discourse of Dianetics: Linguistic Manifestations of Violence Toward Queerness in the Canonical Religious Philosophy of Scientology

Relics, Remnants, and Religion: An Undergraduate Journal in Religious Studies Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 5-5-2017 The Dangerous Discourse of Dianetics: Linguistic Manifestations of Violence Toward Queerness in the Canonical Religious Philosophy of Scientology Francesca Retana University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/relics Recommended Citation Retana, Francesca (2017) "The Dangerous Discourse of Dianetics: Linguistic Manifestations of Violence Toward Queerness in the Canonical Religious Philosophy of Scientology," Relics, Remnants, and Religion: An Undergraduate Journal in Religious Studies: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/relics/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Relics, Remnants, and Religion: An Undergraduate Journal in Religious Studies by an authorized editor of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Retana: The Dangerous Discourse of Dianetics: Linguistic Manifestations Page 1 of 45 The Dangerous Discourse of Dianetics: Linguistic Manifestations of Violence Toward Queerness in the Canonical Religious Philosophy of Scientology I. Uncovering the Anti-Queer Sentiment in the Dianetic Perspective At present, there is a groundswell of public sensational interest in the subject of Scientology; and, in fact, in the time since I began this research paper, a nine-episode documentary series has premiered and reached finale on A&E titled “Scientology and the Aftermath”— a personal project hosted by sitcom celebrity, ex-Scientologist, and author of Troublemaker: Surviving Hollywood and Scientology, Leah Remini.1 I could not begin to enumerate the myriad exposés/memoirs of ex-Scientologists that have been published in recent years nor could I emphasize enough the rampant conspiracy theories that are at the disposal of any curious mind on what many have termed “the cult” of Scientology. -

Scientology: a Way of Spiritual Self-Identification

SCIENTOLOGY: AWAY O F S PIRITUAL SELF-IDENTIFICATION Michael A. Sivertsev, Ph.D. Chairman for New Religions Board of Cooperation with Religious Organisations Office of the Russian President V FREEDOM PUBLISHING SCIENTOLOGY: A WAY OF SPIRITUAL SELF-IDENTIFICATION Michael A. Sivertsev, Ph.D. Chairman for New Religions Board of Cooperation with Religious Organisations Office of the Russian President V FREEDOM PUBLISHING FREEDOM PUBLISHING 6331 HOLLYWOOD BOULEVARD, SUITE 1200 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90028-6329 TEL: (213) 960-3500 FAX: (213) 960-3508/3509 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE PAGE 1 I. SCIENTOLOGY AS A THEOLOGICAL SYSTEM . PAGE 5 I.I. THE CHARISMATIC LEADER . PAGE 5 I.II. SCIENTOLOGY: THE RELIGIOUS DOCTRINE AND THE HOLY KNOWLEDGE . PAGE 7 II. THE PROBLEM OF PRESERVATION OF HOLY KNOWLEDGE . PAGE 8 II.I. ESOTERIC KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENTOLOGY TECHNOLOGY . PAGE 8 II.II. PROCEDURES FOR INITIATION INTO KNOWLEDGE AS A TECHNOLOGY OF ACHIEVEMENT OF THE HIGHEST LEVELS OF CONSCIOUSNESS. LEVELS OF SELF-IDENTIFICATION: FROM PRECLEAR TO THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF SPIRITUAL BEING . PAGE 10 II.III. “THE BRIDGE TO TOTAL FREEDOM” AS A CENTER AND BASIS OF THE SCIENTOLOGY THEOLOGICAL SYSTEM . PAGE 11 III. THE STRUCTURE OF THE ’SPIRITUAL MESSAGE OF SCIENTOLOGY . PAGE 12 III.I. THE FALL OF MAN, AWARENESS OF THE FALL (CATASTROPHE), SELF-TRANSFORMATION: A HERO’ S PERSONAL JOURNEY . PAGE 12 III.II. CONFESSION, SELF-UNDERSTANDING, SALVATION: THE PATH OF RELIGIOUS SERVICE . PAGE 13 IV. UNDERSTANDING THE ABSOLUTE: STRUCTURES OF NEW EXISTENCE, HIGHEST EXISTENCE . PAGE 14 IV.I. PERSONAL OR IMPERSONAL EXISTENCE . PAGE 14 IV.II. CONTINUITY OR DISCONTINUITY OF BEHAVIOUR BETWEEN PHYSICAL UNIVERSE (MEST) AND SPIRITUAL BEING . -

L. Ron Hubbard FOUNDER of DIANETICS and SCIENTOLOGY Volume POWER & SOLO

The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology by L. Ron Hubbard FOUNDER OF DIANETICS AND SCIENTOLOGY Volume POWER & SOLO CONFIDENTIAL Contents Power Power Processes 19 Power Badges 20 Power Processes 21 Six Power Processes 22 The Standard Flight To Power & VA 23 Gain The Ability To Handle Power 25 The Power Processes 26 Power Process 1AA (Pr Pr 1AA) 32 Power Process 1 (Pr Pr 1) 32 Power Process 2 (Pr Pr 2) 32 Power Process 3 (Pr Pr 3) 32 Power Process 4 (Pr Pr 4) 32 Power Process 5 (Pr Pr 5) 33 Power Process 6 (Pr Pr 6) 33 The Power Processes All Flows 34 Data On Pr Prs 37 End Phenomena And F/ Ns In Power 38 L P - 1 40 Low TA Cases 41 Power Plus 43 Restoring The Knowledge You Used To Have 45 Power Plus Release - 5A Processes 46 Power Plus Processes All Flows 47 Rehab Of VA 48 GPM Research Material 51 Editors Note 53 Routine 3 54 Current Auditing 59 Routine 3M Rundown By Steps 61 Correction To HCO Bulletin Of February 22, 1963 66 R3M Goal Finding By Method B 67 Routine 2 And 3M Correction To 3M Steps 13, 14 68 Vanished RS Or RR 71 The End Of A GPM 74 R2- R3 Corrections Typographicals And Added Notes 79 Routine 3M Simplified 80 R3M2 What You Are Trying To Do In Clearing 89 Routine 3M2 Listing And Nulling 92 Routine 3M2 Corrected Line Plots 96 R3M2 Redo Goals On This Pattern 103 Routine 3M2 Directive Listing 107 Routine 3M2 Handling The GPM 109 Routine 3M2 Tips - The Rocket Read Of A Reliable Item 113 Routine 3 An Actual Line Plot 115 7 Routine 3 Directive Listing Listing Liabilities 120 Routine 3 Correction To HCOB 23 Apr. -

Dear Matt, While I Understand Your Predicament, I Fully Understand The

Dear Matt, While I understand your predicament, I fully understand the situation you and your ASA colleagues find yourselves in. It is not often one has to deal with an organisation as deceptive as The Way To Happiness Foundation. To cut to the chase - while the ASA acknowledges the connection between The Way To Happiness Foundation and Scientology, the ASA believes that The Way To Happiness Foundation is a separate charity in its own right. I intend to present evidence establishing the following four points: 1) The Way To Happiness Foundation is under control of Scientology international management. 2) The Way To Happiness Foundation is run by Scientologists. 3) The Way To Happiness Foundation is being run for the purpose of Scientology. 4) A proportion of donations collected by The Way To Happiness Foundation go to Scientology. If the above four points are true, then the claim that The Way To Happiness Foundation is a separate charity in its own right must be rejected, and future advertisements on behalf of this group must clearly reflect this. 1. The IRS application and decision. I will begin by revisiting the IRS position. The 1023 IRS filing made in 1993 as part of The Way To Happiness Foundation’s application for tax-exemption is available from http://www.xenu-directory.net/documents/corporate/irs/1993-1023-twth.pdf . From page 10 that 1023 filing: Evidence piece 1 From page 9 of that same document: Evidence piece 2 Evidence piece 3 From the 1993 IRS closing agreement that gave The Way To Happiness Foundation and other Scientology entities their tax-exemption, Scientology-related entities qualifying for tax-exemption are defined thus (http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Cowen/essays/agreemnt.html#Scientology- related%20entity ): “4. -

TRAINING, the WAY to HAPPINESS by L

THE AUDITORS® THE MONTHLY JOURNAL OF SCIENTOLOGY TRAINING, THE WAY TO HAPPINESS by L. Ron Hubbard When a person who has read a popular do it all from scratch. Scientology training text on Scientology turns to an organiza is an instruction book on the self-not an tion for training, he will discover himself instruction book on the body or how you studying in a far more intense form should be a good boy or girl in the material on which he has already agreed. society, an instruction book on self. Scientology is a plan of thinking and a Man is basically good and he gets all way of looking at things and arranging mixed up — when you unmix him he new answers which are just as good as reverts to being good. they are workable. We are not dedicated We are moving toward the attainment to theory, we are dedicated to what by Man of a new level of freedom, works. decency and happiness. We can do it. Simply teaching somebody about Sci And it is a lot more than worthwhile—it entology, simply training somebody will is vital that we do so. For there is no bring him up tone. Training is not to help elsewhere. And just now nobody make a Professional with a shingle out. cares but us. It is vital to be trained just to handle life. Scientology is the only complete and If you think that a trained Scientologist thorough explanation of existence. The is someone who only audits, then you principles and axioms of Scientology have a very limited view of Scientology. -

Scientology in Court: a Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion

DePaul Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 Fall 1997 Article 4 Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion Paul Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Paul Horwitz, Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion, 47 DePaul L. Rev. 85 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCIENTOLOGY IN COURT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND SOME THOUGHTS ON SELECTED ISSUES IN LAW AND RELIGION Paul Horwitz* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 86 I. THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY ........................ 89 A . D ianetics ............................................ 89 B . Scientology .......................................... 93 C. Scientology Doctrines and Practices ................. 95 II. SCIENTOLOGY AT THE HANDS OF THE STATE: A COMPARATIVE LOOK ................................. 102 A . United States ........................................ 102 B . England ............................................. 110 C . A ustralia ............................................ 115 D . Germ any ............................................ 118 III. DEFINING RELIGION IN AN AGE OF PLURALISM -

SCIENTOLOGY and DIANETICS Search for Incidents on the Track

SCIENTOLOGY AND DIANETICS BOOKLET 27 of the PROFESSIONAL COURSE BY L. RON HUBBARD Search for Incidents on the Track Ron's Org Grenchen Switzerland SEARCH FOR INCIDENTS 2 Professional Course Booklet 27 ON THE TRACK TO THE STEADFAST AND LOYAL SUPPORTERS OF TOMORROW AND THE THINKING MEN OF YESTERDAY COMPILED IN WRITTEN FORM BY D. FOLGERE AKA RICHARD DE MILLE COPYRIGHT 1952 BY L. RON HUBBARD ADDITIONAL STUDY MATERIAL FOR THIS LECTURE MAY BE FOUND IN THE FOLLOWING BOOKS: ADVANCED PROCEDURE AND AXIOMS SELF ANALYSIS HANDBOOK FOR PRECLEARS DIANETICS: MODERN SCIENCE OF MENTAL HEALTH (1950) SCIENCE OF SURVIVAL (1951) SYMBOLOGICAL PROCESSING LECTURES OF L. RON HUBBARD PAMPHLET COVERS ONE LECTURE COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEMS (HOW TO LIVE THOUGH AN EXECUTIVE) INDIVIDUAL TRACK MAP WHAT TO AUDIT SCANNED, TYPED AND PROCESSED INTO READABLE AND DIGITAL FORM BY RON'S ORG GRENCHEN, SWITZERLAND WWW.RONSORG.CH SEARCH FOR INCIDENTS 3 Professional Course Booklet 27 ON THE TRACK SEARCH FOR INCIDENTS ON THE TRACK 1. DEMONSTRATION Aud: Did you have to protect the information about hypnotism? Pc: Yes. Aud: And you have been holding back that kind of information ever since? What if somebody in the MEST universe learned about how you got into this home universe? Who are you keeping the information from? Pc: (Mumbled) Aud: Can you be thrown out of this universe and enslaved by the MEST universe? If anybody knew the secret of the theta universe, could he then have an almost unlimited number of slaves? Pc: Yes. but they wouldn't want them. Aud: They wouldn't want them? Who wouldn't want them? Some of these people in the MEST universe? Pc: I don't think the people in the theta universe would want them. -

Comparison Between Freedom of Religion in Germany and in the United States in General and the Treatment of the Church of Scientology Specifically

University of Georgia School of Law Digital Commons @ Georgia Law LLM Theses and Essays Student Works and Organizations 2000 COMPARISON BETWEEN FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN GERMANY AND IN THE UNITED STATES IN GENERAL AND THE TREATMENT OF THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY SPECIFICALLY WOLFGANG EICHELE University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/stu_llm Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Repository Citation EICHELE, WOLFGANG, "COMPARISON BETWEEN FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN GERMANY AND IN THE UNITED STATES IN GENERAL AND THE TREATMENT OF THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY SPECIFICALLY" (2000). LLM Theses and Essays. 284. https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/stu_llm/284 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works and Organizations at Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in LLM Theses and Essays by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARISON BEMI^Filii i^:;l^ IN ; GERiAIW AND IN THE UNITED sIteSS:^ IN GEERAL ;; AND THE TREATIVInT i^' Tft I ^ • : CHURCH OF SCENTOL OG Y SPEGFICALIY :ang Eichele The University of Georgia Alexander Campbell King Law Library UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA LAW LIBRARY 3 8425 00347 5154 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2013 http://arcliive.org/details/comparisonbetweeOOeicli COMPARISON BETWEEN FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN GERMANY AND IN THE UNITED STATES IN GENERAL AND 1 HE TREATMENT OF THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY SPECIFICALLY by WOLFGANG EICHELE 1. -

De Sus Sistemas Religiosos Y Doctrinas

SCIENTOLOGY: ANÁLISIS Y COMPARACIÓN de sus SISTEMas RELIGIOSOS Y DOCTRINas Doctor Bryan R. Wilson, Miembro Emérito Universidad de Oxford Inglaterra Febrero de 1995 LAT Scn Analysis and Comparison Cover.indd 1-2 APPROVED 3/8/2017 18:50 LAT Scn Analysis and Comparison Cover.indd 3-4 APPROVED 3/8/2017 18:50 SCIENTOLOGY: ANÁLISIS Y COMPARACIÓN de sus SISTEMAS RELIGIOSOS Y DOCTRINAS LAT Scn Analysis and Comparison.indd 1 APPROVED 3/5/2017 20:26 LAT Scn Analysis and Comparison.indd 2 APPROVED 3/5/2017 20:26 Scientology: análisis y comparación de sus sistemas religiosos y doctrinas ÍNDICE I. La diversidad de las religiones y los problemas de definición 1 II. Los rasgos distintivos de la religión 6 III. Sistemas de creencia no teístas 10 IV. Lenguaje religioso y evolución de la teología cristiana 13 V. Funciones sociales y morales de la religión 17 VI. Breve descripción de Scientology 22 VII. Análisis sociológico de la evolución de la Iglesia de Scientology 34 VIII. Conceptos de culto y salvación 41 IX. La evaluación de Scientology por los eruditos 49 X. Scientology y otras religiones 54 XI. Los rasgos distintivos de la religión aplicados a Scientology 56 LAT Scn Analysis and Comparison.indd 3 APPROVED 3/5/2017 20:26 LAT Scn Analysis and Comparison.indd 4 APPROVED 3/5/2017 20:26 SCIENTOLOGY: ANÁLISIS Y COMPARACIÓN de sus SISTEMAS RELIGIOSOS Y DOCTRINAS Doctor Bryan R. Wilson, Miembro Emérito Universidad de Oxford Inglaterra Febrero de 1995 I. La diversidad de las religiones y los problemas de definición I.I. Elementos de la definición de religión No existe una definición definitiva de religión que sea generalmente aceptada por los eruditos. -

L. Ron Hubbard Common-Sense Moral Code Is the Failures of Psychiatry 36 Achieving Remarkable Success in Schools

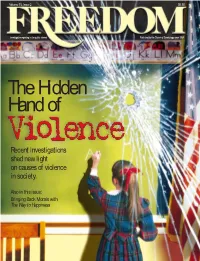

Volume 31, Issue 2 $2.50 Investigative reporting in the public interest Published by the Church of Scientology since 1968 The Hidden Hand of Violence Recent investigations shed new light on causes of violence in society. Also in this issue: Bringing Back Morals with The Way to Happiness From the Editor’s Desk has been eroded through the last four decades of “progressive education” — a system designed more for psychological conditioning than academic success. The Add the wholesale labeling of children with psychiatric “disorders” (such as “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” and a host of “Learning Disorders”) for exhibiting much of what was previously considered normal childhood behavior. Erosion These labels not only excuse the educa- tional shortcomings of our schools, but the youth who receive them are told that they are responsible neither for what they do nor for the decisions they make. In fact, and of Right perhaps not so coincidentally, the Denver Post reported in December 1996 that federal law prohibited the expulsion of three kids who passed a gun around at school because they were classified as and “special-education” students. These stu- dents were not considered responsible for what they did. Finally, add a chemical catalyst of mind- altering psychiatric drugs and the result is volatile and even deadly. Keep in mind, too, Wrong that the types of “special education” students who are not held responsible for nalert Feeding Christians to lions was once popu- passing around deadly weapons at school columnist lar “sport.” For centuries, public executions are the ones most likely to be on such drugs.