The Moving Average Ratio and Momentum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Test of Macd Trading Strategy

A TEST OF MACD TRADING STRATEGY Bill Huang Master of Business Administration, University of Leicester, 2005 Yong Soo Kim Bachelor of Business Administration, Yonsei University, 200 1 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In the Faculty of Business Administration Global Asset and Wealth Management MBA O Bill HuangIYong Soo Kim 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Bill Huang 1 Yong Soo Kim Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: A Test of MACD Trading Strategy Supervisory Committee: Dr. Peter Klein Senior Supervisor Professor, Faculty of Business Administration Dr. Daniel Smith Second Reader Assistant Professor, Faculty of Business Administration Date Approved: SIMON FRASER . UNI~ER~IW~Ibra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "lnstitutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: ~http:llir.lib.sfu.calhandlell8921112~)and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if .technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

The Best Candlestick Patterns

Candlestick Patterns to Profit in FX-Markets Seite 1 RISK DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Bernstein Bank GmbH, exclusively for the purposes of an informational presentation by Bernstein Bank GmbH. The presentation must not be modified or disclosed to third parties without the explicit permission of Bernstein Bank GmbH. Any persons who may come into possession of this information and these documents must inform themselves of the relevant legal provisions applicable to the receipt and disclosure of such information, and must comply with such provisions. This presentation may not be distributed in or into any jurisdiction where such distribution would be restricted by law. This presentation is provided for general information purposes only. It does not constitute an offer to enter into a contract on the provision of advisory services or an offer to buy or sell financial instruments. As far as this presentation contains information not provided by Bernstein Bank GmbH nor established on its behalf, this information has merely been compiled from reliable sources without specific verification. Therefore, Bernstein Bank GmbH does not give any warranty, and makes no representation as to the completeness or correctness of any information or opinion contained herein. Bernstein Bank GmbH accepts no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any expense, loss or damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use of all or any part of this presentation. This presentation may contain forward- looking statements of future expectations and other forward-looking statements or trend information that are based on current plans, views and/or assumptions and subject to known and unknown risks and uncertainties, most of them being difficult to predict and generally beyond Bernstein Bank GmbH´s control. -

Candlestick Patterns

INTRODUCTION TO CANDLESTICK PATTERNS Learning to Read Basic Candlestick Patterns www.thinkmarkets.com CANDLESTICKS TECHNICAL ANALYSIS Contents Risk Warning ..................................................................................................................................... 2 What are Candlesticks? ...................................................................................................................... 3 Why do Candlesticks Work? ............................................................................................................. 5 What are Candlesticks? ...................................................................................................................... 6 Doji .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Hammer.............................................................................................................................................. 7 Hanging Man ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Shooting Star ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Checkmate.......................................................................................................................................... 9 Evening Star .................................................................................................................................... -

Bearish Belt Hold Line

How to Day Trade using the Belt Hold Line Pattern Belt Hold Line Definition The belt hold line candlestick is basically the white marubozu and black marubozu within the context of a trend. The bullish belt hold candle opens on the low of the day and closes near the high. This candle presents itself in a downtrend and is an early sign that there is a potential bullish reversal. Conversely the bearish belt candle opens at the high of the day and closes near the low. This candle presents itself in an uptrend and is an early sign that there is a potential bearish reversal. These candles are reliable reversal bars, but lose their importance if there are a number of belt hold lines in close proximity. Not to complicate the matter further, but the pattern can also act as a continuation pattern, which we will cover later in this post. Bullish Belt Hold Line The bullish belt hold line gaps down on the open of the bar, which represents the low of the bar, and then rallies higher. Shorts who entered positions on the open of the bar are now underwater, which adds to the buying frenzy. Bullish Belt Hold Line You are now looking at a chart which shows the bullish belt hold line candlestick pattern. As you see, the trading day starts with a big bearish gap, which is the beginning of the pattern. The price action then continues with a big bullish candle. The candle has no lower candle wick and closes at its high. This price action confirms both a bullish marubozu and bullish belt hold line pattern. -

Cup with Handle

9 Cup with Handle RESULTS SNAPSHOT Upward Breakouts Appearance Looks like a cup profile with the handle on the right. Reversal or continuation Short-term bullish continuation Bull Market Bear Market Performance rank 13 out of 23 9 out of 19 Break-even failure rate 5% 7% Average rise 34% 23% Change after trend ends –30% –34% Volume trend Downward Upward Throwbacks 58% 42% Percentage meeting price target 50% 27% Surprising findings Patterns that are tall, have short handles, and a higher left cup lip perform better. See also Bump-and-Run Reversal Bottom; Rounded Bottom This pattern sports a low failure rate but a below average rise when compared to other chart pattern types. The Results Snapshot shows the numbers. A few surprises are unique to this pattern. A cup with a short handle (shorter than the median length) tends to outperform those with longer handles. If the left cup 149 150 Cup with Handle lip is higher than the right, the postbreakout performance is also slightly bet- ter. The higher left lip is a change from the first edition of this Encyclopedia where cups with a higher right lip performed better. I believe the difference is from the change in methodology and a larger sample size. Tour The cup-with-handle formation was popularized by William J. O’Neil in his book, How to Make Money in Stocks (McGraw-Hill, 1988). He gives a couple of examples such as that shown in Figure 9.1. The stock climbed 295% in about 2 months (computed from the right cup lip to the ultimate high). -

Eliminates Emotionsemotions

Candlestick Forum Boot Camp High Profit Patterns Why is it important to know the patterns? EliminatesEliminates emotionsemotions 1 Advanced Candlestick Patterns ¾ Fry Pan Bottom ¾ Dumpling Top ¾ Cradle Pattern ¾ Jay-Hook ¾ Scoop Pattern ¾ Belt Hold ¾ Breakout Patterns High Probabilty Patterns Pennants Channels Fibonacci Distance from MA’s Double Bottoms/Tops Fry Pan Bottom The downtrend starts waning with the appearance of small trading bodies As the trend starts slowly curling up, a gap up in price indicates that strong buying sentiment has now returned 2 Fry Pan Bottom Long Rounded Curved bottom Fry Pan Bottom – minutes, days, months The indecisive rounding bottom is the predominant factor Fry Pan Bottom - Past Analysis Big Percent move at top has a different meaning when a pattern can be identified 3 Fry Pan Bottom measuring point A dimple usually marks the Halfway point Fry pan bottom Fry Pan Bottom - Dollar analysis 4 Fry Pan Bottom expectations Should not have breached bottom curvature Fry pan Bottom – Failure Fry Pan Bottom – where to buy? 5 Fry Pan Bottom with MA confirmation Fry Pan Bottom - A Break Out or Failure? Easy identification of a failure, which makes for easy stop loss procedures Fry Pan Bottom can become a Cup and Handle CUP Handle Or a J-hook pattern 6 What shows a Fry Pan Bottom failure? Fry Pan Bottom – Exuberant buying Want to see break out buying Fry Pan Bottom –What to expect? 7 Fry Pan Bottom – What is expected? Opposite the Fry pan Bottom Dumpling Top The Dumpling Top- an identifiable characteristic Lousy trading atmosphere 8 Cradle Pattern • The Cradle Pattern is a symmetric bottom pattern that is easy to identify. -

The Predictive Power of Price Gaps

The Predictive Power of Price Gaps Robert Mois* Eric Teder** Stockholm School of Economics Stockholm School of Economics Bachelor Thesis Stockholm School of Economics Department of Finance Tutor: Paolo Sodini May 30, 2012 Abstract Price gaps are identified by studying trading ranges, which is the spread between a stock’s highest and lowest traded price over a trading day. If the trading ranges of two consecutive days do not overlap, a price gap has occurred. A positive gap is when the lowest traded price of the day is higher than the highest traded price of the precedent day. For negative gaps, the highest traded price of the day is lower than the lowest traded price the day before. Our hypothesis is that abnormal returns can be generated from buying stocks after a positive gap and from short-selling stocks after a negative gap. Using transaction data from the Swedish stock market from 2000 through 2010, we test our hypothesis. First we map returns and abnormal returns, generated from risk-adjusting models, for holding periods of one to five days. The abnormal returns are then the base for executed regressions, run in order to test the explanatory power of positive and negative price gaps. From our analysis, we find support for our hypothesis that trading on positive gaps generates abnormal returns. These abnormal returns persist even after taking transaction costs into account. The same support is not found for negative gaps. According to our findings, price gaps seem to constitute an anomaly. Keywords: Price gaps, Technical analysis, Momentum, Candlesticks First and foremost, we would like to thank our tutor Paolo Sodini, Associate Professor at the Department of Finance at the Stockholm School of Economics, for generous support and valuable input throughout the work with this thesis. -

Individually and on Behalf of All Others Similarly Situated, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS _____________, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, v. CBOE GLOBAL MARKETS, INC., CBOE HOLDINGS, INC., CBOE FUTURES EXCHANGE, LLC, CHICAGO BOARD JURY TRIAL DEMANDED OPTIONS EXCHANGE, INC., and JOHN DOES 1-20 Defendants. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page NATURE OF THE ACTION ..........................................................................................................3 PARTIES .........................................................................................................................................8 A. Plaintiff ....................................................................................................................8 B. Defendants ...............................................................................................................9 JURISDICTION AND VENUE ....................................................................................................10 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................11 A. Futures and Options Contracts ...............................................................................11 B. The SPX and SPX Options ....................................................................................12 C. The VIX .................................................................................................................14 D. VIX Options, VIX Futures, VIX ETPs, and the “SOQ” Settlement -

Passive Funds Affect Prices: Evidence from the Most ETF Dominated Asset

BIS Working Papers No 952 Passive funds affect prices: Evidence from the most ETF- dominated asset classes by Karamfil Todorov Monetary and Economic Department July 2021 JEL classification: G11, G13, G23. Keywords: ETF, leverage, commoditization, VIX, futures. BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The papers are on subjects of topical interest and are technical in character. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS. This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2021. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISSN 1020-0959 (print) ISSN 1682-7678 (online) Passive Funds Affect Prices: Evidence from the Most ETF-dominated Asset Classes KARAMFIL TODOROV∗ ABSTRACT This paper studies exchange-traded funds’ (ETFs) price impact in the most ETF- dominated asset classes: volatility (VIX) and commodities. I propose a model- independent approach to replicate the VIX futures contract. This allows me to isolate a non-fundamental component in VIX futures prices that is strongly related to the rebalancing of ETFs. To understand the source of that component, I decom- pose trading demand from ETFs into three parts: leverage rebalancing, calendar rebalancing, and flow rebalancing. Leverage rebalancing has the largest effects. It amplifies price changes and exposes ETF counterparties negatively to variance. Keywords: ETF, leverage, commoditization, VIX, futures JEL classification: G11, G13, G23 ∗London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Finance and Bank for International Settlements. -

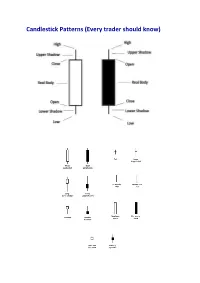

Candlestick Patterns (Every Trader Should Know)

Candlestick Patterns (Every trader should know) A doji represents an equilibrium between supply and demand, a tug of war that neither the bulls nor bears are winning. In the case of an uptrend, the bulls have by definition won previous battles because prices have moved higher. Now, the outcome of the latest skirmish is in doubt. After a long downtrend, the opposite is true. The bears have been victorious in previous battles, forcing prices down. Now the bulls have found courage to buy, and the tide may be ready to turn. For example = INET Doji Star A “long-legged” doji is a far more dramatic candle. It says that prices moved far higher on the day, but then profit taking kicked in. Typically, a very large upper shadow is left. A close below the midpoint of the candle shows a lot of weakness. Here’s an example of a long-legged doji. For example = K Long-legged Doji A “gravestone doji” as the name implies, is probably the most ominous candle of all, on that day, price rallied, but could not stand the altitude they achieved. By the end of the day. They came back and closed at the same level. Here ’s an example of a gravestone doji: A “Dragonfly” doji depicts a day on which prices opened high, sold off, and then returned to the opening price. Dragonflies are fairly infrequent. When they do occur, however, they often resolve bullishly (provided the stock is not already overbought as show by Bollinger bands and indicators such as stochastic). For example = DSGT The hangman candle , so named because it looks like a person who has been executed with legs swinging beneath, always occurs after an extended uptrend The hangman occurs because traders, seeing a sell-off in the shares, rush in to grab the stock a bargain price. -

Dow Theory & Gap Theory

Axioms of Stocks & Options (A2) Notebook 1: Dow Theory & Gap Theory Dow Theory & Gap Theory Dow Theory: ___________ Journalist Started the publication named the ____ Street Journal Dow Jones Industrials and Transportation averages arose from their investigative research into _______ behaviour ______ Dow essentially hypothesised what became the foundation of modern technical analysis Dow Theory Principles: 1. The _____ Discounts Everything 2. The Market Has _____ Trends 3. Trends Have Three _____ 4. The _____ Must Confirm Each Other 5. ______ Must Confirm The Trend 6. A trend is in effect until it has given definite signals that it has _______ 1. The Price Discounts Everything: All known information (fundamental) that can be known, is already reflected in the _____ price Because everything known is priced into a stock price – all we have left to measure is market ________ and human behaviour Technical Analysts recognise the cognitive factors that impinge rational behaviour 2. Three Trends of the Market: 1) P______ 2) I_________ 3) M______ Axioms of Stocks & Options A2 2 Notebook 1: Dow Theory & Gap Theory Primary Trend: _______ term trend (Macro Trend) __ year + Secondary Trend: __________ trend 3 - 9 _______ ______ lines Works with the ______ trend Minor Trend: ____ term trend ______ to a couple of weeks Works with the ________ trend Three Trends of the Market: Primary: ____ of the ocean Intermediate: _____ Minor: _____ Human sentiment defines the wave 3. Trends Have Three Phases 1. A____________ 2. Public P________ -

4 Strategies for Day Trading Morning Gaps with E-Mini Futures

4 Strategies for Day Trading Morning Gaps with E-Mini Futures Gap trading can be one of the simplest of technical trading approaches to day trade the futures markets. Gaps are a common phenomenon in the stock markets where the pre-market and after hours markets tend to see prices gap higher or lower. The popularity of trading gaps is seen by the fact that it is often employed by professional futures day traders and also the simple to understand rules makes it a perfect way to get started with technical analysis trading. The E-mini futures contracts being one of the most popular of the stock index futures trading contracts is known for the fact that price action respects the technical analysis. It is not uncommon to find various E-mini trading strategies and among the different approaches to trading E-mini futures contracts, trading with gaps is one of the easiest of all trading methods whether you want to trade the E-mini S&P500 or the E-mini Dow futures contracts. The basics of trading gaps with E-mini futures is to look for price that gaps above or below from the previous day or session. This usually happens either after the markets reopen from the trading break or at the start of a new trading week or a trading day. Gaps can also occur during the pre-market trading hours and just before official trading starts as well as intraday depending on any unscheduled news or event which hasn’t yet been discounted by price. In order to trade gaps with the E-mini futures successfully, we need to understand what are price gaps and why they are formed.