Long-Term Monitoring Reveals Differential Responses of Mussel and Host Fish Communities in a Biodiversity Hotspot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Mississippi Bird EA

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Managing Damage and Threats of Damage Caused by Birds in the State of Mississippi Prepared by United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services In Cooperation with: The Tennessee Valley Authority January 2020 i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Wildlife is an important public resource that can provide economic, recreational, emotional, and esthetic benefits to many people. However, wildlife can cause damage to agricultural resources, natural resources, property, and threaten human safety. When people experience damage caused by wildlife or when wildlife threatens to cause damage, people may seek assistance from other entities. The United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services (WS) program is the lead federal agency responsible for managing conflicts between people and wildlife. Therefore, people experiencing damage or threats of damage associated with wildlife could seek assistance from WS. In Mississippi, WS has and continues to receive requests for assistance to reduce and prevent damage associated with several bird species. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to incorporate environmental planning into federal agency actions and decision-making processes. Therefore, if WS provided assistance by conducting activities to manage damage caused by bird species, those activities would be a federal action requiring compliance with the NEPA. The NEPA requires federal agencies to have available -

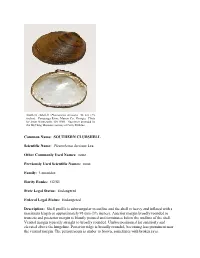

SOUTHERN CLUBSHELL Scientific Name: Pleurobema Decisum Lea

Southern clubshell (Pleurobema decisum) 56 mm (2¼ inches). Conasauga River, Murray Co., Georgia. Photo by Jason Wisniewski, GA DNR. Specimen provided by the McClung Museum courtesy of Gerry Dinkins. Common Name: SOUTHERN CLUBSHELL Scientific Name: Pleurobema decisum Lea Other Commonly Used Names: none Previously Used Scientific Names: none Family: Unionidae Rarity Ranks: G2/S1 State Legal Status: Endangered Federal Legal Status: Endangered Description: Shell profile is subtriangular in outline and the shell is heavy and inflated with a maximum length or approximately 93 mm (3¾ inches). Anterior margin broadly rounded to truncate and posterior margin is bluntly pointed and terminates below the midline of the shell. Ventral margin typically straight to broadly rounded. Umbos positioned far anteriorly and elevated above the hingeline. Posterior ridge is broadly rounded, becoming less prominent near the ventral margin. The periostracum is amber to brown, sometimes with broken rays. Pseudocardinal teeth are heavy and lateral teeth are long and slightly curved. Umbo cavity shallow. Nacre color typically white. Similar Species: The genus Pleurobema is generally regarded as one of the most difficult of genera to identify. Even the most seasoned malacologists find mussels in this genus to be extremely difficult to identify due to very few, or subtle differing, conchological characteristics. Williams et al. (2008) recognize two species that strongly resemble the southern clubshell and should be referenced to obtain a detailed list of similar species and characteristics to distinguish between these species. As a result, no similar species will be discussed in this account. Habitat: Typically occupies large streams to large rivers with moderate flow and sand or gravel substrates; sometimes found in pools with slow or no current. -

Environmental Report (ER) (TVA 2003) in Conjunction with Its Application for Renewal of the BFN Ols, As Provided for by the Following NRC Regulations

Biological Assessment Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant License Renewal Review Limestone County, Alabama October 2004 Docket Numbers 50-259, 50-260, and 50-296 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Rockville, Maryland Biological Assessment of the Potential Effects on Endangered or Threatened Species from the Proposed License Renewal for the Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant 1.0 Introduction The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licenses the operation of domestic nuclear power plants in accordance with the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended, and NRC implementing regulations. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) operates Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant, Units 1, 2, and 3 (BFN) pursuant to NRC operating license (OL) numbers DPR-33, DPR-52, DPR-68, which expire on December 20, 2013, June 28, 2014, and July 2, 2016, respectively. TVA has prepared an Environmental Report (ER) (TVA 2003) in conjunction with its application for renewal of the BFN OLs, as provided for by the following NRC regulations: C Title 10 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 54, “Requirements for Renewal of Operating Licenses for Nuclear Power Plants,” Section 54.23, Contents of application - environmental information (10 CFR 54.23). C Title 10 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 51, “Environmental Protection Regulations for Domestic Licensing and Related Regulatory Functions,” Section 51.53, Postconstruction environmental reports, Subsection 51.53(c), Operating license renewal stage (10 CFR 51.53(c)). The renewed OLs would allow up to 20 additional years of plant operation beyond the current licensed operating term. No major refurbishment or replacement of important systems, structures, or components are expected during the 20-year BFN license renewal term. -

February 27, 2017 Ms. Amber Tubbs Mcgehee Engineering Corp. P.O

STATE OF ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES 64 NORTH UNION STREET, SUITE 464 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 ROBERT BENTLEY PATRICIA J. POWELL, DIRECTOR GOVERNOR STATE LANDS DIVISION N. GUNTER GUY, JR. TELEPHONE (334) 242-3484 COMMISSIONER FAX NO (334) 242-0999 CURTIS JONES DEPUTY COMMISSIONER February 27, 2017 Ms. Amber Tubbs McGehee Engineering Corp. P.O. Box 3431 Jasper, AL 35502-3431 RE: Sensitive Species Information request Southland Resources, Inc. - Searles Mine No. 10 Dear Ms. Tubbs: The Natural Heritage Section office received your e-mail dated 2/24/2017 addressed to Ashley Peters on 2/27/2017 and has since developed the following information pertaining to sensitive species (state protected, and federally listed candidate, threatened, and endangered species). I have enclosed a list of sensitive species which the Natural Heritage Section Database or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have indicated occur or have occurred in Tuscaloosa County. Additionally, I have listed some potentially helpful and informative web sites at the end of this letter. The Natural Heritage Section database contains numerous records of sensitive species in Tuscaloosa County. Our database indicates the area of interest has had no biological survey performed at the delineated location, by our staff or any individuals referenced in our database. Therefore we can make no accurate assessment to the past or current inhabitancy of any federal or state protected species at that location. A biological survey conducted by trained professionals is the most accurate way to ensure that no sensitive species are jeopardized by the development activities. The closest sensitive species is recorded in our database as occurring approximately 5.4 miles from the subject site. -

September 24, 2018

September 24, 2018 Sent via Federal eRulemaking Portal to: http://www.regulations.gov Docket Nos. FWS-HQ-ES-2018-0006 FWS-HQ-ES-2018-0007 FWS-HQ-ES-2018-0009 Bridget Fahey Chief, Division of Conservation and Classification U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 5275 Leesburg Pike, MS: ES Falls Church, VA 22041-3808 [email protected] Craig Aubrey Chief, Division of Environmental Review Ecological Services Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 5275 Leesburg Pike, MS: ES Falls Church, VA 22041 [email protected] Samuel D. Rauch, III National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Protected Resources 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 [email protected] Re: Proposed Revisions of Endangered Species Act Regulations Dear Mr. Aubrey, Ms. Fahey, and Mr. Rauch: The Southern Environmental Law Center (“SELC”) submits the following comments in opposition to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s and National Marine Fisheries Service’s proposed revisions to the Endangered Species Act’s implementing regulations.1 We submit these comments on behalf of 57 organizations working to protect the natural resources of the 1 Revision of the Regulations for Prohibitions to Threatened Wildlife and Plants, 83 Fed. Reg. 35,174 (proposed July 25, 2018) (to be codified at 50 C.F.R. pt. 17); Revision of Regulations for Interagency Cooperation, 83 Fed. Reg. 35,178 (proposed July 25, 2018) (to be codified at 50 C.F.R. pt. 402); Revision of the Regulations for Listing Species and Designating Critical Habitat, 83 Fed. Reg. 35,193 (proposed July 25, 2018) (to be codified at 50 C.F.R. -

Alasmidonta Varicosa) Version 1.1.1

Species Status Assessment Report for the Brook Floater (Alasmidonta varicosa) Version 1.1.1 Molunkus Stream, Tributary of the Mattawamkeag River in Maine. Photo credit: Ethan Nedeau, Biodrawversity. Inset: Adult brook floaters. Photo credit: Jason Mays, USFWS. July 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service This document was prepared by Sandra Doran of the New York Ecological Services Field Office with assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Brook Floater Species Status Assessment (SSA) Team. The team members include Colleen Fahey, Project Manager (Species Assessment Team (SAT), Headquarters (HQ) and Rebecca Migala, Assistant Project Manager, (Region 1, Regional Office), Krishna Gifford (Region 5, Regional Office), Susan (Amanda) Bossie (Region 5 Solicitor's Office, Julie Devers (Region 5, Maryland Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Jason Mays (Region 4, Asheville Field Office), Rachel Mair (Region 5, Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery), Robert Anderson and Brian Scofield (Region 5, Pennsylvania Field Office), Morgan Wolf (Region 4, Charleston, SC), Lindsay Stevenson (Region 5, Regional Office), Nicole Rankin (Region 4, Regional Office) and Sarah McRae (Region 4, Raleigh, NC Field Office). We also received assistance from David Smith of the U.S. Geological Survey, who served as our SSA Coach. Finally, we greatly appreciate our partners from Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada, the Brook Floater Working Group, and others working on brook floater conservation. Version 1.0 (June 2018) of this report was available for selected peer and partner review and comment. Version 1.1 incorporated comments received on V 1.0 and was used for the Recommendation Team meeting. This final version, (1.1.1), incorporates additional comments in addition to other minor editorial changes including clarifications. -

Sensitive Species Information Request Alabama Land Resources, Inc

STATE OF ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES 64 NORTH UNION STREET, SUITE 464 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 KAY IVEY STATE LANDS DIVISION GOVERNOR PATRICIA POWELL MCCURDY DIRECTOR CHRISTOPHER M. BLANKENSHIP COMMISSIONER HANK BURCH ASSISTANT DIRECTOR EDWARD F. POOLOS DEPUTY COMMISSIONER TELEPHONE (334) 242-3484 FAX (334) 242-0999 March 26, 2021 Mr. L. Stephen Blankenship McGehee Engineering Corp. P.O. Box 3431 Jasper, AL 35502-3431 RE: Sensitive Species Information request Alabama Land Resources, Inc. - Mine No. 3 – Revision R-23 Dear Mr. Blankenship: The Natural Heritage Section office received your e-mail dated 3/26/2021 addressed to Ashley Peters on 3/26/2021 and has since developed the following information pertaining to sensitive species (state protected, and federally listed candidate, threatened, and endangered species). I have enclosed a list of sensitive species which the Natural Heritage Section Database or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have indicated occur or have occurred in Jefferson County. Additionally, I have listed some potentially helpful and informative web sites at the end of this letter. The Natural Heritage Section database contains numerous records of sensitive species in Jefferson County. Our database indicates the area of interest has had no biological survey performed at the delineated location, by our staff or any individuals referenced in our database. Therefore, we can make no accurate assessment to the past or current inhabitancy of any federal or state protected species at that location. A biological survey conducted by trained professionals is the most accurate way to ensure that no sensitive species are jeopardized by the development activities. -

Changes in the Freshwater Mussel Assemblage in the East Fork Tombigbee River, Mississippi: 1988–2011

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2013 Department of Biology CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD August 2013 APPROVED BY: Dr. Michael M. Gangloff Chairperson, Thesis Committee Dr. Robert P. Creed Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Mike D. Madritch Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Sue L. Edwards Chairperson, Department of Biology Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Byron Hamstead 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 Byron Hamstead B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Michael Gangloff The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway is among the largest and most expensive environmental engineering projects of the 20th century. The waterway accommodates barge navigation between the Tennessee River drainage and Mobile River Basin through a series of locks, dams, canals, and dredged and diverted streams. These alterations have destroyed much riverine habitat and fragmented remaining aquatic habitats resulting in isolated freshwater mussel populations in patches of streams like the East Fork Tombigbee River, where 42 species were historically known. The first post-waterway mussel surveys in 1987 and 1988 reported 31 taxa (including 2 federally-listed species). -

Changes in the Freshwater Mussel Assemblage in the East Fork Tombigbee River, Mississippi: 1988–2011

CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2013 Department of Biology CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD August 2013 APPROVED BY: Dr. Michael M. Gangloff Chairperson, Thesis Committee Dr. Robert P. Creed Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Mike D. Madritch Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Sue L. Edwards Chairperson, Department of Biology Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Byron Hamstead 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 Byron Hamstead B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Michael Gangloff The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway is among the largest and most expensive environmental engineering projects of the 20th century. The waterway accommodates barge navigation between the Tennessee River drainage and Mobile River Basin through a series of locks, dams, canals, and dredged and diverted streams. These alterations have destroyed much riverine habitat and fragmented remaining aquatic habitats resulting in isolated freshwater mussel populations in patches of streams like the East Fork Tombigbee River, where 42 species were historically known. The first post-waterway mussel surveys in 1987 and 1988 reported 31 taxa (including 2 federally-listed species). I sampled 70 sites in 2010 and 2011 using both quadrats and timed searches and found 29 species to be extant. -

In Mississippi National Forests

SUMMARY Little is known about the distribution of freshwater mussels in Mississippi national forests. Review of the scant available infor- mation revealed that the national forests harbor a diverse mus- sel fauna of possibly 46 or more species (including confirmed, probable, and potential occurrences). Occurrence of 33 species is confirmed. Because of the geographic, physiographic, and drain- age basin diversity of Mississippi national forests, there is con- siderable variation in mussel communities among the national forests. Three distinct fauna1 groups are represented in Missis- sippi national forests, each with a characteristic assemblage of species. One species of potential occurrence is a federally endan- gered species, 1 species of confirmed occurrence is a candidate for listing, and 11 species of confirmed or probable occurrence are considered of special concern by the American Fisheries Society (Williams and others 1993). None of the national forests have been surveyed adequately, and specific population data are almost com- pletely lacking. This review of existing information represents the first of a three-phase program needed to comprehensively evalu- ate the mussel resources of Mississippi national forests. Phase two involves an exhaustive, qualitative field survey of Mississippi national forests to document precise distribution of species and location of important communities. Phase three consists of a quan- titative study of important communities in order to assess repro- ductive characteristics and viability and to establish baseline density estimates for monitoring of future population trends. Cover: left, Lampsilis cardium; top right, Utterbackia imbecillis; bottom right, Potamilus ohiensis. Current Distributional Information on Freshwater Mussels (family Unionidae) in Mississippi National Forests Wendell R. -

Evolution of Active Host-Attraction Strategies in the Freshwater Mussel Tribe Lampsilini (Bivalvia: Unionidae)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41 (2006) 195–208 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Evolution of active host-attraction strategies in the freshwater mussel tribe Lampsilini (Bivalvia: Unionidae) David T. Zanatta ¤, Robert W. Murphy Royal Ontario Museum, Department of Natural History, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ont., Canada M5S 2C6 Received 17 October 2005; revised 21 May 2006; accepted 22 May 2006 Available online 3 June 2006 Abstract Most freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionoida) require a host, usually a Wsh, to complete their life cycle. Most species of mussels show adaptations that increase the chances of glochidia larvae contacting a host. We investigated the evolutionary relationships of the freshwa- ter mussel tribe Lampsilini including 49 of the approximately 100 extant species including 21 of the 24 recognized genera. Mitochondrial DNA sequence data (COI, 16S, and ND1) were used to create a molecular phylogeny for these species. Parsimony and Bayesian likeli- hood topologies revealed that the use of an active lure arose early in the evolution of the Lampsiline mussels. The mantle Xap lure appears to have been the Wrst to evolve with other lure types being derived from this condition. Apparently, lures were lost independently in sev- eral clades. Hypotheses are discussed as to how some of these lure strategies may have evolved in response to host Wsh prey preferences. © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Freshwater mussels; Host-attraction strategies; Lures; Unionoida; Lampsilini; Phylogenetic systematics 1. Introduction Mantle lures in these species are useful to attract preda- cious Wsh since several species of Lampsilis (e.g., L. siliquoi- Freshwater mussels (also known as unionids, naiads, or dea, L. -

Mississippi Natural Heritage Program Animals

MISSISSIPPI NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM LISTED SPECIES OF MISSISSIPPI 2011 GLOBAL FEDERAL STATE STATE SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME RANK STATUS STATUS RANK ANIMALS BIVALVIA Actinonaias ligamentina Mucket G5 LE S1 Cyclonaias tuberculata Purple Wartyback G5 LE S1 Elliptio arctata Delicate Spike G3Q LE S1 Elliptio dilatata Spike G5 LE S1 Epioblasma brevidens Cumberlandian Combshell G1 LE, XN LE S1 Epioblasma penita Southern Combshell G1 LE LE S1 Epioblasma triquetra Snuffbox G3 LE S1 Hamiota perovalis Orangenacre Mucket G2 LT LE S1 Lexingtonia dolabelloides Slabside Pearlymussel G2 C LE S1 Medionidus acutissimus Alabama Moccasinshell G2 LT LE S1 Plethobasus cyphyus Sheepnose G3 C LE S1 Pleurobema curtum Black Clubshell G1 LE LE SH Pleurobema decisum Southern Clubshell G2 LE LE S1S2 Pleurobema marshalli Flat Pigtoe GH LE LE SX Pleurobema perovatum Ovate Clubshell G1 LE LE S1 Pleurobema rubrum Pyramid Pigtoe G2 LE S1 Pleurobema taitianum Heavy Pigtoe G1 LE LE SX Potamilus capax Fat Pocketbook G1 LE LE S1 Potamilus inflatus Inflated Heelsplitter G1G2 LT LE S1 Ptychobranchus fasciolaris Kidneyshell G4G5 LE S1 Quadrula cylindrica cylindrica Rabbitsfoot G3T3 LE S1 Quadrula metanevra Monkeyface G4 LE SX Quadrula stapes Stirrupshell GH LE LE SX MALACOSTRACA Fallicambarus gordoni Camp Shelby Burrowing Crayfish G1 LE S1 INSECTA Neonympha mitchellii mitchellii Mitchell’s Satyr G2T2 LE S1 Nicrophorus americanus American Burying Beetle G2G3 LE LE SX OSTEICHTHYES Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi Gulf Sturgeon G3T2 LT LE S1 Crystallaria asprella Crystal Darter