Appendix C: Status and Life History of the Eight Assessed Mussels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTRIBUTICNAL ANALYSIS of the FP.Esh"WA'l'e.H MUSSEL FAUNA

DISTRIBUTICNAL ANALYSIS OF THE FP.ESh"WA'l'E.H MUSSEL FAUNA OF THE TENNESSEE RT·lER SiSTE.'1, WIT"'.d SPECIAL REF:::::",.ENCE TO POSSIBLE LIMITI:~G EFFECTS OF SILTATIO.\l by Sally D. Dennis Dissertation su~mitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Stat~ University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCIOR OF PHILOSOPHY in zoolog'J APPROVED: E. F. Benfi~la, Chairman r A. L. 3u1keiJ¢, Jr. A. c. Eehdncks l 1 R. A Paterson D. i1. ??irter H. van der Scha..:.:e August, 1984 B2.acksburg, Virginia DISTRIBUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL FAUNA OF THE TENNESSEE RIVER SYSTEM, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO POSSIBLE LIMITING EFFEcrS OF SILTATION by sally D. Dennis (ABSTRAcr} Mussel studies in the Tennessee River drainage (1973 - 1982} examined ecology and distribution and investigated factors limiting to distribution~ This river system presently supports 71 freshwater mussel species, 25% of which are endemic to the Cumberlandian Region. Species have been extirpated from this drainage within the past 60 years, however the number of extant species remains high. The major impact of man's activities has been reduction of available habitat Past and present distribution records indicate that mussel species assemblages are determined by geologic history and stream size. Although some overlap of species exists among stream size categories, there is no longer a continuous gradation from one category to the next; mussels exist in isolated conmunities separated by nonproductive river reaches. Productive reaches supporting more than 60 mussel species once existed in habitats spanning the transition from medium to large rivers; reaches now altered by impoundment. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Interim Performance Report Endangered Species

INTERIM PERFORMANCE REPORT ENDANGERED SPECIES PROGRAM GRANT NUMBER F17AP01052 WILDLIFE PROJECTS – ALABAMA PROJECT Reproductive Characteristics and Host Fish Determination of Canoe Creek Clubshell, Pleurobema athearni (Gangloff et al. 2006) in Big Canoe Creek drainage (Etowah and St. Clair Counties), Alabama October 1, 2018 - September 30, 2020 ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES WILDLIFE AND FRESHWATER FISHERIES DIVISION Prepared by: Todd B. Fobian Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries PROJECT Reproductive Characteristics and Host Fish Determination of Canoe Creek Clubshell, Pleurobema athearni (Gangloff et al. 2006) in the Big Canoe Creek drainage (Etowah and St. Clair Counties), Alabama Year 1 Interim Report State: Alabama Introduction Pleurobema athearni (Gangloff et al, 2006), Canoe Creek Clubshell is currently a candidate for federally threatened/endangered status by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). It is Coosa Basin endemic, with historical records only known from the Big Canoe Creek (BCC) system in Alabama (Gangloff et al. 2006, Williams et al. 2008). Recent surveys completed by ADCNR and USFWS established the species is extant at six localities in the basin, with two in Upper Little Canoe Creek (ULCC), one in Lower Little Canoe Creek (LLCC), and three in BCC proper. (Fobian et al. 2017). As culture methods improve, propagated P. athearni juveniles could soon be available to support reintroduction/augmentation efforts within historical range. Little is known about Pleurobema athearni reproduction, female brooding period, or glochidial hosts. Female P. athearni are presumed short term-brooders and likely gravid from late spring to early summer (Gangloff et al. 2006, Williams et al. 2008). Glochidial hosts are currently unknown although other Mobile River Basin Pleurobema species often utilize Cyprinidae (shiners) to complete metamorphosis (Haag and Warren 1997, 2003, Weaver et al. -

FINAL Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL)

FINAL Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) For Organic Enrichment & Dissolved Oxygen Tombigbee River (Aliceville Reservoir) AL/03160106-0402-102 Pickens County, Alabama Prepared by: US EPA Region 4 61 Forsyth Street SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 October 2008 Tombigbee River (Aliceville Reservoir) FINAL – Organic Enrichment/Dissolved Oxygen Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................. iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................ iv List of Abbreviations..................................................................................................... v 1.0 Executive Summary.................................................................................... 1 2.0 Basis for the §303(d) Listing...................................................................... 4 3.0 Technical Basis for TMDL Development................................................... 7 3.1 Applicable Water Quality Criterion....................................................................... 7 3.2 Source Assessment.................................................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Nonpoint Sources........................................................................................................ 9 3.2.2 Point Sources............................................................................................................ 10 3.3 Data Availability -

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Endangered Species Expenditure Report (1998)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Federal and State Endangered and Threatened Species Expenditures Fiscal Year 1998 January 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................... ii What is the purpose of this report? ....................................................................................................... ii What expenditures are reported?.......................................................................................................... ii What expenditures are not included?.................................................................................................... ii What are the expenditures reported for FY 1998?................................................................................ ii How does the 1998 expenditure report compare to other years? ......................................................... ii ENDANGERED SPECIES EXPENDITURES FISCAL YEAR 1998...................................................1 PURPOSE.............................................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................1 What does "Reasonably Identifiable Expenditures" mean? .........................................................1 What is not included in the report? ...............................................................................................2 -

REPORT FOR: Preliminary Analysis for Identification, Distribution, And

REPORT FOR: Preliminary Analysis for Identification, Distribution, and Conservation Status of Species of Fusconaia and Pleurobema in Arkansas Principle Investigators: Alan D. Christian Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, P.O. Box 599, State University, Arkansas 72467; [email protected]; Phone: (870)972-3082; Fax: (870)972-2638 John L. Harris Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, P.O. Box 599, State University, Arkansas 72467 Jeanne Serb Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, 251 Bessey Hall, Ames, Iowa 50011 Graduate Research Assistant: David M. Hayes, Department of Environmental Science, P.O. Box 847, State University, Arkansas 72467: [email protected] Kentaro Inoue, Department of Environmental Science, P.O. Box 847, State University, Arkansas 72467: [email protected] Submitted to: William R. Posey Malacologist and Commercial Fisheries Biologist, AGFC P.O. Box 6740 Perrytown, Arkansas 71801 April 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY There are currently 13 species of Fusconaia and 32 species of Pleurobema recognized in the United States and Canada. Twelve species of Pleurobema and two species of Fusconaia are listed as Threatened or Endangered. There are 75 recognized species of Unionidae in Arkansas; however this number may be much higher due to the presence of cryptic species, many which may reside within the Fusconaia /Pleurobema complex. Currently, three species of Fusconaia and three species of Pleurobema are recognized from Arkansas. The true conservation status of species within these genera cannot be determined until the taxonomic identity of populations is confirmed. The purpose of this study was to begin preliminary analysis of the species composition of Fusconaia and Pleurobema in Arkansas and to determine the phylogeographic relationships within these genera through mitochondrial DNA sequencing and conchological analysis. -

Freshwater Mussel Survey of Clinchport, Clinch River, Virginia: Augmentation Monitoring Site: 2006

Freshwater Mussel Survey of Clinchport, Clinch River, Virginia: Augmentation Monitoring Site: 2006 By: Nathan L. Eckert, Joe J. Ferraro, Michael J. Pinder, and Brian T. Watson Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries Wildlife Diversity Division October 28th, 2008 Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 4 Objective ............................................................................................................................ 5 Study Area ......................................................................................................................... 6 Methods.............................................................................................................................. 6 Results .............................................................................................................................. 10 Semi-quantitative .................................................................................................. 10 Quantitative........................................................................................................... 11 Qualitative............................................................................................................. 12 Incidental............................................................................................................... 12 Discussion........................................................................................................................ -

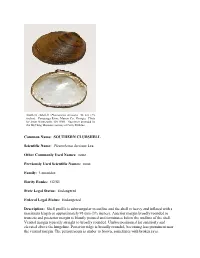

SOUTHERN CLUBSHELL Scientific Name: Pleurobema Decisum Lea

Southern clubshell (Pleurobema decisum) 56 mm (2¼ inches). Conasauga River, Murray Co., Georgia. Photo by Jason Wisniewski, GA DNR. Specimen provided by the McClung Museum courtesy of Gerry Dinkins. Common Name: SOUTHERN CLUBSHELL Scientific Name: Pleurobema decisum Lea Other Commonly Used Names: none Previously Used Scientific Names: none Family: Unionidae Rarity Ranks: G2/S1 State Legal Status: Endangered Federal Legal Status: Endangered Description: Shell profile is subtriangular in outline and the shell is heavy and inflated with a maximum length or approximately 93 mm (3¾ inches). Anterior margin broadly rounded to truncate and posterior margin is bluntly pointed and terminates below the midline of the shell. Ventral margin typically straight to broadly rounded. Umbos positioned far anteriorly and elevated above the hingeline. Posterior ridge is broadly rounded, becoming less prominent near the ventral margin. The periostracum is amber to brown, sometimes with broken rays. Pseudocardinal teeth are heavy and lateral teeth are long and slightly curved. Umbo cavity shallow. Nacre color typically white. Similar Species: The genus Pleurobema is generally regarded as one of the most difficult of genera to identify. Even the most seasoned malacologists find mussels in this genus to be extremely difficult to identify due to very few, or subtle differing, conchological characteristics. Williams et al. (2008) recognize two species that strongly resemble the southern clubshell and should be referenced to obtain a detailed list of similar species and characteristics to distinguish between these species. As a result, no similar species will be discussed in this account. Habitat: Typically occupies large streams to large rivers with moderate flow and sand or gravel substrates; sometimes found in pools with slow or no current. -

1988007W.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF FIGURES n LIST OF TABLES w LIST OF APPENDICES iv ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 1 I OBJECTIVES OF STUDY 3 ∎ METHODS 3 I DESCRIPTION OF STUDY AREA 7 RESULTS 7 SPECIES ACCOUNTS 13 Federally Endangered Species 13 Federal Candidate Species 15 I Proposed State Endangered Species 15 Proposed State Threatened Species 16 Watch List Species 16 Other Species 17 I Introduced Species 33 ∎ DISCUSSION 33 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 LITERATURE CITED 36 I I I I LIST OF FIGURES PAGE Figure 1 . Collection sites in the Little Wabash River drainage, 1988 6 Figure 2. The Little Wabash River and its tributaries 8 Figure 3. Number of individuals collected liver per site in the Little Wabash River (main channel) in 1988 12 I Figure 4 . Number of species collected per site in the Little Wabash River (main channel) in 1988 12 I I I I I I LIST OF TABLES PAGE Table 1 . Comparison of the mussel species of the Little Wabash River reported by Baker (1906) and others [pre-1950], Fechtner (1963) [1951-53], Parmalee [1954], Matteson [1956], INHS [1957-88], and this study 4 Table 2 . Collection sites in the Little Wabash River drainage, 1988 5 Table 3 . Total,rank order of abundance and percent composition of the mussel species collected live in the Little Wabash River drainage, 1988 9 Table 4. Site by site listing of all mussel species collected in the Little Wabash River drainage, 1988 10-11 Table 5. Site by site listing of all mussel species collected by M .R . Matteson in the Little Wabash River, 1956 14 I I iii LIST OF APPENDICES PAGE Appendix I . -

Environmental Report (ER) (TVA 2003) in Conjunction with Its Application for Renewal of the BFN Ols, As Provided for by the Following NRC Regulations

Biological Assessment Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant License Renewal Review Limestone County, Alabama October 2004 Docket Numbers 50-259, 50-260, and 50-296 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Rockville, Maryland Biological Assessment of the Potential Effects on Endangered or Threatened Species from the Proposed License Renewal for the Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant 1.0 Introduction The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licenses the operation of domestic nuclear power plants in accordance with the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended, and NRC implementing regulations. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) operates Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant, Units 1, 2, and 3 (BFN) pursuant to NRC operating license (OL) numbers DPR-33, DPR-52, DPR-68, which expire on December 20, 2013, June 28, 2014, and July 2, 2016, respectively. TVA has prepared an Environmental Report (ER) (TVA 2003) in conjunction with its application for renewal of the BFN OLs, as provided for by the following NRC regulations: C Title 10 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 54, “Requirements for Renewal of Operating Licenses for Nuclear Power Plants,” Section 54.23, Contents of application - environmental information (10 CFR 54.23). C Title 10 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 51, “Environmental Protection Regulations for Domestic Licensing and Related Regulatory Functions,” Section 51.53, Postconstruction environmental reports, Subsection 51.53(c), Operating license renewal stage (10 CFR 51.53(c)). The renewed OLs would allow up to 20 additional years of plant operation beyond the current licensed operating term. No major refurbishment or replacement of important systems, structures, or components are expected during the 20-year BFN license renewal term. -

February 27, 2017 Ms. Amber Tubbs Mcgehee Engineering Corp. P.O

STATE OF ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES 64 NORTH UNION STREET, SUITE 464 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 ROBERT BENTLEY PATRICIA J. POWELL, DIRECTOR GOVERNOR STATE LANDS DIVISION N. GUNTER GUY, JR. TELEPHONE (334) 242-3484 COMMISSIONER FAX NO (334) 242-0999 CURTIS JONES DEPUTY COMMISSIONER February 27, 2017 Ms. Amber Tubbs McGehee Engineering Corp. P.O. Box 3431 Jasper, AL 35502-3431 RE: Sensitive Species Information request Southland Resources, Inc. - Searles Mine No. 10 Dear Ms. Tubbs: The Natural Heritage Section office received your e-mail dated 2/24/2017 addressed to Ashley Peters on 2/27/2017 and has since developed the following information pertaining to sensitive species (state protected, and federally listed candidate, threatened, and endangered species). I have enclosed a list of sensitive species which the Natural Heritage Section Database or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have indicated occur or have occurred in Tuscaloosa County. Additionally, I have listed some potentially helpful and informative web sites at the end of this letter. The Natural Heritage Section database contains numerous records of sensitive species in Tuscaloosa County. Our database indicates the area of interest has had no biological survey performed at the delineated location, by our staff or any individuals referenced in our database. Therefore we can make no accurate assessment to the past or current inhabitancy of any federal or state protected species at that location. A biological survey conducted by trained professionals is the most accurate way to ensure that no sensitive species are jeopardized by the development activities. The closest sensitive species is recorded in our database as occurring approximately 5.4 miles from the subject site.