Most Corrupt: Representative Darrell Issa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

2012 Election Results Coastal Commission Legislative Report

STATE OF CALIFORNIA—NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY EDMUND G. BROWN, JR., GOVERNOR CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION 45 FREMONT, SUITE 2000 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105- 2219 VOICE (415) 904- 5200 FAX (415) 904- 5400 TDD (415) 597-5885 W-19a LEGISLATIVE REPORT 2012 ELECTION—CALIFORNIA COASTAL DISTRICTS DATE: January 9, 2013 TO: California Coastal Commission and Interested Public Members FROM: Charles Lester, Executive Director Sarah Christie, Legislative Director Michelle Jesperson, Federal Programs Manager RE: 2012 Election Results in Coastal Districts This memo describes the results of the 2012 elections in California’s coastal districts. The November 2012 General Election in California was the first statewide election to feel the full effect of two significant new electoral policies. The first of these, the “Top Two Candidates Open Primary Act,” was approved by voters in 2010 (Proposition 14). Under the new system, all legislative, congressional and constitutional office candidates now appear on the same primary ballot, regardless of party affiliation. The two candidates receiving the most votes in the Primary advance to the General Election, regardless of party affiliation. The June 2012 primary was the first time voters utilized the new system, and the result was numerous intra-party competitions in the November election as described below. The other significant new factor in this election was the newly drawn political districts. The boundaries of legislative and congressional seats were redrawn last year as part of the decennial redistricting process, whereby voting districts are reconfigured based on updated U.S. Census population data. Until 2011, these maps have been redrawn by the majority party in the Legislature, with an emphasis on party registration. -

December 13, 2010 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker, U.S. House

December 13, 2010 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable John Boehner Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives Minority Leader, U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Edolphus Towns The Honorable Darrell Issa Chairman, Committee on Oversight and Ranking Member, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Government Reform U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Lacy Clay The Honorable Patrick McHenry Chairman, Subcommittee on Information Policy, Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Information Census and National Archives Policy, Census and National Archives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Committee on Oversight and Government Reform U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi, Leader Boehner, Chairman Towns, Ranking Member Issa, Chairman Clay, and Ranking Member McHenry, With Senate passage of the “Census Oversight Efficiency and Management Reform Act of 2010” (S. 3167/H.R. 4945) by unanimous consent on December 8, we write to urge swift bipartisan passage of the Senate-approved bill in order for it to reach the President’s desk by year’s end. The bill represents an unprecedented opportunity to enact reasonable administrative reforms and grant the Census Bureau Director new authorities to run the agency more efficiently, openly, and authoritatively, all at no additional cost to the taxpayer. In particular, we support the bill’s proposal to create a five-year Presidential appointment for the Census Director. This important change would allow the Census Bureau to avoid disruptions caused by changes in administration, especially around the period of the decennial census. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

Fact Sheet: the House Health Repeal Bill's Impact on California

Fact Sheet: The House Health Repeal Bill’s Impact on California A year ago, a majority of the House of Representatives, including Representatives Doug LaMalfa, Tom McClintock, Paul Cook, Jeff Denham, David Valadao, Devin Nunes, Kevin McCarthy, Steve Knight, Ed Royce, Ken Calvert, Mimi Walters, Dana Rohrabacher, Darrell Issa, and Duncan Hunter, voted for and passed the so-called “American Health Care Act,” or AHCA, a health repeal bill that would have cut coverage, increased costs, and eliminated protections for millions of Californians. The bill would have imposed an “age tax,” letting insurers charge people over 50 five times more for coverage, and put the health of one in five Americans on Medicaid in jeopardy, including seniors, children, and people with disabilities. While Californians would have lost out, the wealthy and insurance and drug companies would have gotten $600 billion in new tax breaks. AHCA Meant Californians Would Have Lost Coverage 2,582,200 Californians Would Have Lost Coverage. In 2026, 2,582,200 Californians would have lost coverage under this bill. 1,578,100 With Medicaid Would Have Lost Coverage. Under the American Health Care Act, 1,578,100 Californians with Medicaid would have lost their coverage. 24,300 Veterans in California Would Have Lost Coverage. Under the American Health Care Act, 24,300 veterans in California would have lost their Medicaid coverage. AHCA Meant Californians Would Have Paid Higher Costs, Especially Older Californians Raise Premiums By Double Digits. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found that a key part of the American Health Care Act, repealing the requirement that most people have health insurance, will premiums 10 percent next year. -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

Mindy Romero, Ph.D. Director 1

Mindy Romero, Ph.D. Director 1. What happened in the 2016 election? 2. What should we expect in 2018? 3. What is the impact of demographic change? Study Methodology Voter Turnout Data •Current Population Survey Population Data •U.S. Census, Current Population Survey, American Community Survey, California Department of Finance 2016 Voter Turnout 2016 U.S. Results Trump = 63 million votes (306) Clinton = 65 million votes + (232) Nearly a 100 million eligible Americans didn’t vote Trump – only about a quarter of eligible voters U.S. 2016 Eligible Voter Turnout Total: 61.4% (61.8% in 2012) White NL: 65.3% (64.1% in 2012) Black: 59.4% (66.2% in 2012) Asian American: 49.9% (48.0% in 2012) Latino: 47.6% (48.0% in 2012) 5 Turnout Paste chart 6 Turnout Paste chart 7 Turnout Paste chart 8 California 2016 Eligible Voter Turnout Total: 57.9% (57.5% in 2012) White NL: 67.1% (64.3% in 2012) Black: 48.4% (61.1% in 2012) Asian American: 52.8% (49.5% in 2012) Latino: 47.2% (48.5% in 2012) 9 Close Margin States 1) Michigan: 10,704 votes (0.5%) 2) New Hampshire: 2,736 votes (0.8%) 3) Pennsylvania: 44,292 votes (1.5%) 4) Wisconsin: 22,748 votes (1.6%) 5) Florida: 112,911 votes (2.3%) 12 6) Minnesota: 44,765 votes (3.3%) 7) Nevada: 27,202 votes (5.0) 8) Maine: 22,142 votes (6.2) 9) Arizona: 91,234 votes (7.3%) 10) North Carolina: 173,315 votes (7.3%) California: 4,269,978 votes (48.8%) 13 Turnout Paste chart 14 Turnout Paste chart 15 Turnout Paste chart 16 Turnout Paste chart 17 Turnout Paste chart 19 Turnout Paste chart 20 Turnout Paste chart -

Communicating with Congress

ONCE A SOLDIER... ALWAYS A SOLDIER Acknowledgment AUSA is grateful to the many Senators and Representatives and their staffs who gave their full cooperation in providing materials for this book. We appreciate the shared photos and memories of their service. We are especially grateful that they continue to care about Soldiers of the United States Army. ONCE A SOLDIER... ALWAYS A SOLDIER Soldiers in the 113th Congress Association of the United States Army Arlington, Virginia Once a Soldier... Dedication Dedicated to the Soldiers who have served in Congress, from the 1st through the 113th. Copyright © 2013 Association of the United States Army All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permis- sion from the Association of the United States Army in writing. Published 2013 Association of the United States Army 2425 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22201 www.ausa.org Manufactured in the USA Eighth Edition Always a Soldier Contents Foreword by Hal Nelson, Brigadier General, USA (Ret) ..................vii Preface by Gordon R. Sullivan, General, USA (Ret), President, Association of the United States Army and former Chief of Staff, United States Army ........................................xi Introduction................................................................................1 Soldiers in the Senate .............................................................3 -

Official List of Members by State

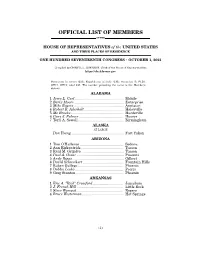

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

US House of Representatives Twitter Handles 115Th Congress

US House of Representatives Twitter Handles 115th Congress State Representative Twitter Handle AK Representative Donald Young @repdonyoung AL Representative Robert Aderholt @robert_aderholt AL Representative Morris Brooks @repmobrooks AL Representative Bradley Byrne @RepByrne AL Representative Gary Palmer @USRepGaryPalmer AL Representative Martha Roby @RepMarthaRoby AL Representative Michael Rogers @RepMikeRogersAL AL Representative Terrycina Sewell @RepTerriSewell AR Representative Eric Crawford @RepRickCrawford AR Representative J. Hill @RepFrenchHill AR Representative Bruce Westerman @RepWesterman AR Representative Stephen Womack @Rep_SteveWomack AR Representative Tom O'Halleran @repohalleran AR Representative Andy Biggs @RepAndyBiggsAZ AS Delegate Aumua Amata @RepAmata Radewagen AZ Representative Trent Franks @RepTrentFranks AZ Representative Ruben Gallego @RepRubenGallego AZ Representative Paul Gosar @RepGosar AZ Representative Raúl Grijalva @RepRaulGrijalva AZ Representative Martha McSally @RepMcSally AZ Representative David Schweikert @RepDavid AZ Representative Kyrsten Sinema @RepSinema CA Representative Peter Aguilar @RepPeteAguilar CA Representative Karen Bass @RepKarenBass CA Representative Xavier Becerra @RepBecerra CA Representative Amerish Bera @RepBera CA Representative Julia Brownley @JuliaBrownley26 CA Representative Kenneth Calvert @KenCalvert CA Representative Tony Cárdenas @RepCardenas CA Representative Judy Chu @RepJudyChu CA Representative Paul Cook @RepPaulCook CA Representative Jim Costa @RepJimCosta CA Representative -

Committees in the 111Th Congress for the Preserving the American Historical Records Act January 2010

Committees in the 111th Congress for the Preserving the American Historical Records Act January 2010 U. S. House of Representatives House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Democrats Republicans Edolphus Towns (D-NY), Chairman Darrell Issa (R-CA), Ranking Minority Member Paul E. Kanjorski (D-PA) Dan Burton (R-IN) Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY) John L. Mica (R-FL) Elijah E. Cummings (D-MD) Mark E. Souder (R-IN) Dennis J. Kucinich (D-OH) John J. Duncan, Jr. (R-TN) John F. Tierney (D-MA) Michael Turner (R-OH) William Lacy Clay (D-MO) Lynn A. Westmoreland (R-GA) Diane E. Watson (D-CA) Patrick T. McHenry (R-NC) Stephen F. Lynch (D-MA) Brian Bilbray (R-CA) Jim Cooper (D-TN) Jim Jordan (R-OH) Gerald E. Connolly (D-VA) Jeff Flake (R-AZ) Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) Jeff Fortenberry (R-NE) Patrick Kennedy (D-RI) Jason Chaffetz (R-UT) Danny Davis (D-IL) Aaron Schock (R-IL) Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) Blaine Luetkemeyer (R-MO) Henry Cuellar (D-TX) Anh “Joseph” Cao (R-LA) Paul W. Hodes (D-NH) Christopher S. Murphy (D-CT) Peter Welch (D-VT) Bill Foster (D-IL) Jackie Speier (D-CA) Steve Driehaus (D-OH) Judy Chu (D-CA) Mike Quigley (D-IL) Marcy Kaptur (D-OH) House Subcommittee on Information Policy, Census and National Archives Democrats Republicans William Lacy Clay (MO), Chairman Patrick McHenry (NC), Ranking Member Lynn Westmoreland (GA), Vice Ranking Paul Kanjorski (PA) Member Carolyn Maloney (NY) Eleanor Holmes Norton (DC) John Mica (FL) Danny Davis (IL) Jason Chaffetz (UT) Steve Driehaus (OH) Diane Watson (CA) Henry Cuellar (D-TX) House Committee on Appropriations Democrats Republicans David R. -

Committee Members Fr: Chairman Adam Schiff Re

UNCLASSIFIED MEMORANDUM November 12, 2019 To: Committee Members Fr: Chairman Adam Schiff Re: Procedures for Impeachment Inquiry Hearings At 10:00 a.m. tomorrow—Wednesday, November 13, 2019—in Room 1100 of the Longworth House Office Building, the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence will hold its first of several open hearings as part of the public phase of the House of Representatives’ impeachment inquiry. Like the depositions preceding them, these hearings will address subjects of profound consequence for the Nation and the functioning of our government under the Constitution. The House’s inquiry into whether grounds exist for President Trump’s impeachment has been, and will continue to be, a sober and rigorous undertaking. The purpose of this memo is to provide Committee Members with information regarding procedures to be observed during the open hearings. The hearings will be conducted in a manner that ensures that all participants are treated fairly and with respect, mindful of the solemn and historic task before us. The hearings will therefore adhere to the Rules of the House and of the Committee, and to H. Res. 660, which established the format the Committee will use during the hearings. These procedures are consistent with those governing prior impeachment proceedings and mirror those used under Republican and Democratic House leadership for decades. • Attendance and Participation. As provided by House Rule XI and H. Res. 660, only Members of the Committee may participate in hearings conducted by the Committee.1 Although Members who are not assigned to the Committee are not permitted to sit on the dais, make statements, or question witnesses, they may of course sit in the audience.