An Interview with Jean- Pierre Bekolo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Continuation of Myth: the Cinematic Representation of Mythic American Innocence in Bernardo Bertolucci’S Last Tango in Paris and the Dreamers

A CONTINUATION OF MYTH: THE CINEMATIC REPRESENTATION OF MYTHIC AMERICAN INNOCENCE IN BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI’S LAST TANGO IN PARIS AND THE DREAMERS Joanna Colangelo A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2007 Committee: Carlo Celli, Advisor Philip Hardy ii ABSTRACT Carlo Celli, Advisor The following thesis aims to track the evolution and application of certain fundamental American cultural mythologies across international borders. While the bulk of my discussion will focus on the cycle of mythic American innocence, I will pay fair attention to the sub-myths which likewise play vital roles in composing the broad myth of American innocence in relation to understanding American identities – specifically, the myth of the Virgin West (or America-as-Eden), the yeoman farmer and individualism. When discussing the foundation of cultural American mythologies, I draw specifically from the traditional myth-symbol writers in American Studies. Those works which I reference are: Henry Nash Smith’s, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth, Leo Marx’s, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America and R.W.B. Lewis’s, The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy, and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century. I focus much of my discussion on the applicability of the myth of innocence, rather than the validity of the actual myth throughout history. In this sense, I follow the myth as a cycle of innocence lost and regained in American culture – as an ideal which can never truly reach its conclusion for as long as America is invested in two broad definitions of innocence: the American Adam and the Noble Savage. -

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

The Honorable Mentions Movies- LIST 1

The Honorable mentions Movies- LIST 1: 1. A Dog's Life by Charlie Chaplin (1918) 2. Gone with the Wind Victor Fleming, George Cukor, Sam Wood (1940) 3. Sunset Boulevard by Billy Wilder (1950) 4. On the Waterfront by Elia Kazan (1954) 5. Through the Glass Darkly by Ingmar Bergman (1961) 6. La Notte by Michelangelo Antonioni (1961) 7. An Autumn Afternoon by Yasujirō Ozu (1962) 8. From Russia with Love by Terence Young (1963) 9. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Sergei Parajanov (1965) 10. Stolen Kisses by François Truffaut (1968) 11. The Godfather Part II by Francis Ford Coppola (1974) 12. The Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky (1975) 13. 1900 by Bernardo Bertolucci (1976) 14. Sophie's Choice by Alan J. Pakula (1982) 15. Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky (1983) 16. Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders (1984) 17. The Color Purple by Steven Spielberg (1985) 18. The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci (1987) 19. Where Is the Friend's Home? by Abbas Kiarostami (1987) 20. My Neighbor Totoro by Hayao Miyazaki (1988) 21. The Sheltering Sky by Bernardo Bertolucci (1990) 22. The Decalogue by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1990) 23. The Silence of the Lambs by Jonathan Demme (1991) 24. Three Colors: Red by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1994) 25. Legends of the Fall by Edward Zwick (1994) 26. The English Patient by Anthony Minghella (1996) 27. Lost highway by David Lynch (1997) 28. Life Is Beautiful by Roberto Benigni (1997) 29. Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson (1999) 30. Malèna by Giuseppe Tornatore (2000) 31. Gladiator by Ridley Scott (2000) 32. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring by Peter Jackson (2001) 33. -

The 2Nd International Film Festival & Awards • Macao Unveils Festival

The 2nd International Film Festival & Awards • Macao unveils festival programme, announces Laurent Cantet as head of jury Macao, 3 November, 2017 The 2nd International Film Festival & Awards • Macao (IFFAM) today announced its programme at a press conference in Macao. The Hong Kong/Macao premiere of Paul King’s Paddington 2 will open the IFFAM on Friday 8 December with the festival running until Thursday 14. The programme includes 10 competition films including the Asian premieres of Venice Film Festival prize winners Foxtrot by Samuel Maoz, and Custody, by Xavier Legrand, as well as Toronto Film Festival breakout Beast, by Michael Pearce and the London Film Festival hit Wrath of Silence, directed by Xin Yukun. For its second edition the IFFAM has exclusively dedicated the feature film competition to films by first and second time film makers with a $60,000 USD prize being awarded to the best feature. The prestigious competition jury comprises of: Laurent Cantet – Director (Jury President) Jessica Hausner - Director Lawrence Osborne - Novelist Joan Chen – Actress / Director Royston Tan – Director Representing the latest style of genre cinema to Asian audiences, highlights from the Flying Daggers strand features Cannes Film Festival smash A Prayer Before Dawn by Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire and Brian Taylor’s Toronto sensation Mom and Dad. The Asian premiere of Saul Dibb’s Journey’s End is screening as an Out-Of-Competition gala alongside Bong Joon-ho’s Okja, showing on the big screen for the first time in the region, and Pen-ek Ratanaruang’s latest movie Samui Song which will be screened with director and cast in attendance. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

And the Ship Sails On

And The Ship Sails On by Serge Toubiana at the occasion of the end of his term as Director-General of the Cinémathèque française. Within just a few days, I shall come to the end of my term as Director-General of the Cinémathèque française. As of February 1st, 2016, Frédéric Bonnaud will take up the reins and assume full responsibility for this great institution. We shall have spent a great deal of time in each other's company over the past month, with a view to inducting Frédéric into the way the place works. He has been able to learn the range of our activities, meet the teams and discover all our on-going projects. This friendly transition from one director-general to the next is designed to allow Frédéric to function at full-steam from day one. The handover will have been, both in reality and in the perception, a peaceful moment in the life of the Cinémathèque, perhaps the first easy handover in its long and sometimes turbulent history. That's the way we want it - we being Costa-Gavras, chairman of our board, and the regulatory authority, represented by Fleur Pellerin, Minister of Culture and Communication, and Frédérique Bredin, Chairperson of the CNC, France's National Centre for Cinema and Animation. The peaceful nature of this handover offers further proof that the Cinémathèque has entered into a period of maturity and is now sufficiently grounded and self-confident to start out on the next chapter without trepidation. But let me step back in time. Since moving into the Frank Gehry building at 51 rue de Bercy, at the behest of the Ministry of Culture, the Cinémathèque française has undergone a profound transformation. -

2013-Mckim-Medal-Gala.Pdf

For Immediate Release 22 April 2013 AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME AWARDS PRESTIGIOUS MCKIM MEDAL TO BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI Bernardo Bertolucci ©Brigitte Lacombe 2012 Rome - The American Academy in Rome has announced that Maestro Bernardo Bertolucci is the 2013 McKim Medal Laureate. The award celebrates the internationally renowned director for exceptional contributions to cinema throughout his career. Bertolucci will be honored with the McKim Medal in Rome on Monday 27 May 2013, which will be presented to him at the 9th annual McKim Medal Gala at Villa Aurelia. Adele Chatfield-Taylor, President and CEO of the American Academy in Rome, stated: “On behalf of the American Academy in Rome, we are delighted to be presenting the 2013 McKim Medal to Maestro Bernardo Bertolucci, one of the most influential film directors of our day. His work has captivated audiences around the world since his earliest efforts. He has challenged the film industry and his viewers by exploring the complex themes that lie at the core of the human condition. We are deeply grateful to our Italian and American donors who underwrite the McKim gala every year; the proceeds make possible fellowships for Italian artists and scholars at the American Academy in Rome!” Bernardo Bertolucci began his cinematic career in 1961, becoming first assistant director to Pier Paolo Pasolini in Accattone. His directorial debut, The Grim Reaper, was based on a story by Pasolini. In 1964 he filmed Before the Revolution, an intimate work that explores existential and political ambiguity, prevalent themes in Bertolucci’s films of the ‘70s. He gained enormous success (and notoriety) with Last Tango in Paris and the historic epic Novecento, followed by The Last Emperor, which received nine Oscars. -

The Companion Film to the EDITED by Website, Womenfilmeditors.Princeton.Edu)

THE FULL LIST OF ALL CLIPS in the film “Edited By” VERSION #2, total running time 1:53:00 (the companion film to the EDITED BY website, WomenFilmEditors.princeton.edu) 1 THE IRON HORSE (1924) Edited by Hettie Gray Baker Directed by John Ford 2 OLD IRONSIDES 1926 Edited by Dorothy Arzner Directed by James Cruze 3 THE FALL OF THE ROMANOV DYNASTY (PADENIE DINASTII ROMANOVYKH) (1927) Edited by Esfir Shub Directed by Esfir Shub 4 MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (CHELOVEK S KINO-APPARATOM) (1929) Edited by Yelizaveta Svilova Directed by Dziga Vertov 5 CLEOPATRA (1934) Edited by Anne Bauchens Directed by Cecil B. De Mille 6 CAMILLE (1936) Edited by Margaret Booth Directed by George Cukor 7 ALEXANDER NEVSKY (ALEKSANDR NEVSKIY) (1938) Edited by Esfir Tobak Directed by Sergei M. Eisenstein and Dmitriy Vasilev 8 RULES OF THE GAME (LA RÈGLE DU JEU) (1939) Edited by Marguerite Renoir Directed by Jean Renoir 9 THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939) Edited by Blanche Sewell Directed by Victor Fleming 10 MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (1943) Edited by Maya Deren Directed by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid 11 IT’S UP TO YOU! (1943) Edited by Elizabeth Wheeler Directed by Henwar Rodakiewicz 12 LIFEBOAT (1944) Edited by Dorothy Spencer Directed by Alfred Hitchcock 13 ROME, OPEN CITY (ROMA CITTÀ APERTA) (1945) Edited by Jolanda Benvenuti Directed by Roberto Rossellini 14 ENAMORADA (1946) Edited by Gloria Schoemann Directed by Emilio Fernández 15 THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI (1947) Edited by Viola Lawrence Directed by Orson Welles 16 LOUISIANA STORY (1948) Edited by Helen van Dongen Directed by Robert Flaherty 17 ALL ABOUT EVE (1950) Edited by Barbara “Bobbie” McLean Directed by Joseph L. -

Ennio Morricone

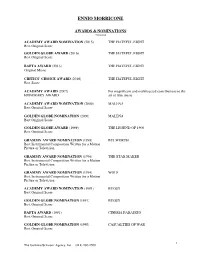

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers.