Common Law Jurisdictions' Response to Persecuted Sexual Minorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veterans, Supporters March on the White House

July 03, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 14 | LGBT Life in Maryland Veterans, Supporters March on the White House WASHINGTON—Several hundred en- thusiastic military veterans and sup- porters, marched on the White House on Saturday, June 27 to protest the discriminatory “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. President Obama and Congress were targeted in the dem- onstration for not acting to repeal the policy that has led to 13,000 individu- als discharged from the Armed Forces since 1993 when the policy went into effect. Many Arabic linguists and other high-skill service members—critical to the war on terrorism and national se- curity—were discharged as a result of the policy. The Servicemembers Legal Net- By Steve Charing work (SLDN) and allies organized the event to help commemorate the 40th On Saturday, June 20, the clouds were still hanging pretty low anniversary of Stonewall. A total of overhead just a couple of hours before the Baltimore Pride Pa- 265 veterans led the march to corre- rade up Charles Street. Earlier in the morning a deluge swept spond to the number of service mem- through the area that concerned potential pride-goers and orga- Photo: Bruce Garrett bers discharged under DADT since nizers alike. It conjured up the lyrics to the iconic Funny Girl song, the President took the oath of office on “Don’t Rain on My Parade.” January 20. Signs and buttons with the Paul Liller (AKA “Dimitria” when doing drag), making his de- number 265 were widely displayed in but as the 2009 Pride Coordinator for the weekend’s festivities, the demonstration. -

Echoes of Imperialism in LGBT Activism

354 Echoes of Empire generated a late nineteenth century politics of imperial Victorian feminism that saw the rescue of distant global sisters as a means towards improving the condition of women in the imperial metropolis. Both temporal contexts present a bewildering array of tendencies: contemporary Western LGBT activism is a deeply divided space, some of whose constituents are complicit in imperial ventures even as others are deeply antagonistic to them. The past is no less complicated a space, so full of Echoes of Imperialism in LGBT Activism contradictory tendencies that it is difficult to regard our ‘postcolonial’ age as self- evidently more progressive or reflexive than times gone by. Rahul Rao The construction of a global discourse of LGBT rights and a politics of LGBT solidarity6 has been empowering for many of its participants. But it has not been an entirely benign development, free from questions of power and hierarchy. Struggles against heteronormativity within Western societies have tended to be marked by a fundamental tension between what might be described as a liberal politics of inclusion or assimilation into the mainstream – marked by such priorities as the At least one early critical reaction to the emergence of the term ‘postcolonial’, right to marry or to serve in the military – and a more radical queer politics that expressed disquiet about its ‘premature1 celebration of the pastness of colonialism’.2 seeks to challenge the very basis of institutions that are seen as oppressive, rather Writing in 1992 and citing the -

Goldv/Aterism

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx BULLETIN STUDENTS FOR A SEPTEMBER 1964 VOLCNOI DEMOCRATIC S e c. G * i • - .• . , . r\ * nn s t e r c, .» ,«>, J SOCIETY PUBLISHED MONTHLY AT 119 FIFTH AVE., ROOM 301, NEW YORK CITY 10003 i n O. K By DOUG IRELAND In what may prove to be the key to building GOLDV/ATERISM a realigned and revitalized Democratic Party, the Mississippi Council of Federate AND HOW IT GREW- Organizations (COFO) is sponsoring a po By JIM WILLIAMS litical challenge to institutionalized racism. The challenge takes the form of The Goldwater phenomenon continues its the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, spread across the American body politic, an interracial group which, primarily causing increasing concern for American under the leadership of SNCC, is sending liberals, radicals and decent people gen an integrated delegation to the Democratic erally. In every community, new strength National Convention this year to challenge is being shown by the Goldwater forces. the seating of the lily-white official slate of delegates. Since the San Francisco convention the following events have taken place: This is but one part of a three-pronged , political attack that marks this year's • (1) Public sentiment is obviously swinging "Freedom Summer." The voter registration toward Goldwater at an unpredicted rate. Before the convention the polls (Lou. Har (continued on page i;) ris, et.al.) showed Goldwater with only 20$ of the public behind him whereas John son had the support of about 73$ of the Sumner BULLETIN Editor: STEVE SLANER, nation. In the very short space of three who is responsible for unsigned articles. -

The New Generation

1/14/13 prorev.com/bush4.htm Behind the Bushes THE NEW GENERATION THE BUSH INDEX DONALD RUMSFELD THE REAL DONALD RUMSFELD DOUG IRELAND, DIRELAND - No man bears greater responsibility for the tragedy of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq than Donald Rumsfeld, yet, though his face and voice are, unfortunately, all too familiar even to the most casual news consumer, most of us have only a rather sanitized conception of who Rumsfeld is, the crucial role he has played at key moments of American history for the last three decades, and what drives him. Roger Morris has now filled the voids in our understanding of Rumsfeld with a brilliant, lengthy essay that lifts the carpet to reveal Rumsfeld's rise and role, and how he led us into an iniquitous war. Roger is one of our finest chroniclers of contemporary history, aRoger_morris masterful dissector of American politics, and a skilled portraitist of the dark side of American power. As a young man with a Ph.D from Harvard, he was a Foreign Service officer and a member of the Senior Staff of the National Security Council under Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Roger Morris resigned from the NSC in protest against the secret invasion of Cambodia in 1970 -- an experience which radicalized him. Since then, he has turned out a series of important, probing books that have contributed mightily to our understanding of our times. Morris's brilliant Rumsfeld dissection -- with the telling title "The Undertaker's Tally" -- is being published by Tom Dispatch in two parts, the first of which has just appeared. -

The Bush Administration, International Family Planning, and Foreign Policy

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 29 Number 3 Article 4 Spring 2004 Politics before Policy: The Bush Administration, International Family Planning, and Foreign Policy Kaci Bishop Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Kaci Bishop, Politics before Policy: The Bush Administration, International Family Planning, and Foreign Policy, 29 N.C. J. INT'L L. 521 (2003). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol29/iss3/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Politics before Policy: The Bush Administration, International Family Planning, and Foreign Policy Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/ vol29/iss3/4 Politics Before Policy: The Bush Administration, International Family Planning, and Foreign Policy I. Introduction Since taking office in January 2001, President George W. Bush has let politics interfere with, and even control, his foreign policy. While all presidents and politicians see the world through the lens of their political beliefs and make policy decisions accordingly, President Bush is so blindly adhering to his politics that his actions negatively impact some of his other stated goals. President Bush made his opposition to abortion clear while he was running for office, yet it was not clear to what extent this belief would impact his policy decisions once he was in office. -

Retracing the New Left: the SDS Outcasts Adam Mikhail

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Retracing the New Left: The SDS Outcasts Adam Mikhail Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES RETRACING THE NEW LEFT: THE SDS OUTCASTS By ADAM MIKHAIL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Adam Mikhail defended this thesis on November 12, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Neil Jumonville Professor Directing Thesis James P. Jones, Jr. Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Lala and Misso, who give and give and give. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for all their help, not only during this thesis process, but throughout my time at Florida State University. I owe special thanks to my major professor, Dr. Neil Jumonville, who first introduced me to the New Left. He challenged me to think big, giving me constant encouragement along the way. I could not have hoped for a more understanding or supportive major professor. His kind words were never taken for granted. For an incredibly thorough editing of my thesis, I express my gratitude to Dr. Kristine Harper, who generously decorated this manuscript with ample amounts of red. -

Promising Democracy Imposing Theocracy

Promising Democracy, Imposing Theocracy: Gender-Based Violence and the US War on Iraq by Yifat Susskind, MADRE Communications Director This report is dedicated to the courageous women of the Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq and to all Iraqis working to build a democratic, secular Iraq free of military occupation and religious coercion. Special thanks to Yanar Mohammed, director of the Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq. MADRE BOARD OF DIRECTORS SPONSORS Holly Near An International Anne H. Hess Julie Belafonte Dr. Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz Women’s Dr. Zala Highsmith-Taylor Vinie Burrows Grace Paley Human Rights Andaye De La Cruz Dr. Johnnetta Cole Bernice Reagon Organization Hilda Díaz Blanche Wiesen Cook Chita Rivera Laura Flanders Clare Coss Helen Rodríguez-Trías, Linda Flores-Rodríguez Alexis De Veaux M.D., 1929-2001 121 West 27th Street, #301 Holly Maguigan Kathy Engel Digna Sánchez New York, NY 10001 Margaret Ratner Roberta Flack Sonia Sánchez Phone: (212) 627-0444 Marie Saint Cyr Devon Fredericks Yolanda Sánchez Fax: (212) 675-3704 Pam Spees Eleanore Kennedy Susan Sarandon www.madre.org Isabel Letelier Julia R. Scott e-mail: [email protected] Audre Lorde, 1934-1992 Susan L. Taylor EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Mary Lumet Marjorie Tuite, 1922-1986 Vivian Stromberg Patricia Maher Alice Walker Monica Melamid Joanne Woodward Hon. Ruth Messinger Billie Jean Young CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Part I. TOWARDS GENDER aPARTHEID IN IRAQ 3 The Iraqi Governing Council Attacks Women’s Rights 3 The Battle over Iraq’s Family Law 4 Iraq’s Constitution: Islamists Appeased 5 Legalizing Violence against Women 6 Part II. -

United States

UNITED STATES 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (G) – January 2003 We don’t want you here, the Navy does’nt want you either. You should have just stayed in your own freakin homo world, with your own kind, at least then youd be somewhat safe, HERE YOUR NOT...........And as long as your in our world you never will be..... Excerpt from a letter left on the windshield of a female sailor's car. [ Spelling and typographical errors from original.] Top left and bottom right: Graffiti found on the walls at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, after a soldier killed another soldier perceived to be gay by beating him with a baseball bat. Bottom left: Written threat left on the windshield of a Marine’s car, 2001. Top right: Written threat left on the vehicle of a sailor, 1996. © 2003 Servicemembers Legal Defense Network UNIFORM DISCRIMINATION: The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Policy of the U.S. Military 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol 15, No. 1 (G) UNITED STATES UNIFORM DISCRIMINATION: The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Policy of the U.S. -

CLGBTH SPRING 2015 1 with Mixed Emotions, We Write Our Final Column

Spring 2015 ó Vol. 28:2/Vol. 29:1 ó http://www.clgbthistory.org IN THIS ISSUE OUTGOING CO-CHAIRS’ COLUMN Fall 2014 Outgoing Co-Chairs’ Column 1 Incoming Co-Chairs’ Column 3 With mixed emotions, we write our final column Prize Winners 4 as co-chairs. We have worked hard these three OAH John D’Emilio Prize 5 years to advance the organization as a space for Calls for Nominations 6 New Book Announcements 7 LGBTQ history and historians to flourish. As two Book Reviews 8 mid-career scholars, we have had to balance Committee on LGBT History commitments with Reviews in this issue obligations at our own institutions, public Mark Cornwall, The Devil’s Wall: The Nationalist Youth history engagement, and family duties. As such, Mission of Heinz Rutha (Geoffrey J. Giles) we have not been able to do all we imagined with St. Sukie De la Croix, Chicago Whispers: A History of LGBT the committee. Still, serving together as co-chairs Chicago before Stonewall (Lance Poston) has been one of the most rewarding experiences of our careers. We have been able support David M. Halperin and Valerie Traub, eds. Gay Shame scholars from graduate students to field leaders, (Jeffrey Cisneros) fundamentally improve the experience of the S.N. Nyeck and Marc Epprecht, eds. Sexual Diversity in AHA annual meeting, strengthen organizational Africa: Politics, Theory, Citizenship (Charles Gossett) infrastructure, and give the CLGBTH a decisive public voice on policy and issues. On a personal Daniel Winunwe Rivers, Radical Relations: Lesbian note, we have also built a lasting friendship with Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since World War II (Gillian Frank) each other for which we are profoundly grateful. -

Doug Ireland, 1946-2013

Doug Ireland, 1946-2013 Doug Ireland, radical journalist, blogger, passionate human rights and queer[1] activist, and relentless scourge of the LGBT establishment, died in his East Village home on Oct. 26. Doug had lived with chronic pain for many years, suffering from diabetes, kidney disease, sciatica and the debilitating effects of childhood polio. In recent years he was so ill that he was virtually confined to his apartment. Towards the end, even writing, his calling, had become extremely difficult. Once, Doug’s writing – in U.S. publications such as the Nation, the Village Voice, New York magazine as well as his blog Direland, and in France Libération and the news website Bakchich – was easy to find. But in recent years his voice was rarely heard outside of New York’s Gay City News, for which he continued to contribute reportage as international editor and political commentary until this year, and few younger radicals are likely to know about him. This is a pity, because Doug’s voice — his scathing polemical style, the vast breadth of his knowledge – was exceptional. Doug was a tireless champion of the oppressed of all kinds, but especially of those who are punished for loving members of their own sex, wherever they might be. For his uncompromising internationalism, his refusaI to allow cultural differences to stand as an excuse for denying LGBT people their human rights, I can think of no one on the left, apart from Peter Tatchell, who was quite like him. Doug was always a man of the left, a libertarian socialist, who nevertheless had long-standing ties to progressives in the Democratic Party – going back to Allard Lowenstein, George McGovern and Bella Abzug, for whom he worked as a campaign manager. -

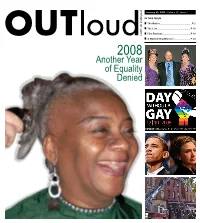

Another Year of Equality Denied

January 02, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 1 IN THIS ISSUE The Outies ............................................... P 2 The List .................................................. P 10 Film Reviews ......................................... P 19 A Manhunting Mormon ........................ P 24 2008 Another Year of Equality Denied 2 q BALTIMORE OUTLOUD January 2, 2009 | baltimoreoutloud.com OUTspoken Publisher Mike Chase [email protected] Executive Editor The OUTIES: Best (or Worst) of 2008 Jim Becker By Steve Charing [email protected] Senior Political Anaylst Senior Political Correspondent Steve Charing Happy New Year, readers! Degeneres David from the Hippo’s Karaoke room In keeping with the year-end tradition Best Hair Studio and Day Spa—Neal’s on Leather Editor Worst Hollywood LGBT Person— Rodney Burger of columnists’ picking the best, worse and Elton John, for his problem with the word Park and Read whatever, I am introducing OUTspoken’s “marriage” during the Prop 8 debate Best Piano Bar— Writers list of the Best (or Worst) of 2008, or the Jeffrey Clagett Jay’s on Read OUTIES. It’ s an unapologetic, biased, Most Supportive Straight TV Chuck Duncan subjective, slanted list of the best (or worst Commentator— Best Change in Bars and Restaurants— Rickie Green in some cases) of politics, culture, the city, Keith Olbermann Ban on smoking. Our lungs get to survive Eva Hersh MD another year. Doug Ireland the state and the scene. Some selections Best Lesbian TV Commentator— P.S. Lorio call for a brief explanation; others clearly Rachel Maddow Best Baltimore Drag Act— Jim Lucio do not. Dimitria Meredith Moise In no particular order, welcome to the Best Local Elected Official on Marriage Ben Ryland 2008 OUTIES: Equality— Comeback of the Year— Nate Sweeney Maryland Attorney General Doug Gansler, Britney Spears MIA - Alexander St. -

Racist Plutocrat Elected Meeting House, 5 Longfellow Park (10-Minute Walk from Harvard Square T Station, West on Brattle St.), Cambridge

Dispatch Newsletter of the May Boston-Cambridge Alliance for Democracy 2007 / see President George W. Bush suffering the "delusions of omnipotence and omniscience" that invariably accompany the concentration of great power in too small a space... and I think of the last Ming emperor, enfolded in the cocoon of his concu- binate, believing that he was the Son of Heaven, informed by his corps of eunuchs that he could command the oceans with a gentle scratching of his vermilion pencil or by subtle move- I ^ ments of his yellow parasol. —Lewis H. Lapham CHAPTER NEWS (Continued on Page 12) Chapter Calendar * * Turning from Empire Ex-Candidate Royal US acting pres. Bush Pres-Elect Sarkozy Boston-Cambridge Alliance for Democracy's next meeting will be on Wednesday, May 23, at 6:45 p.m. at Cambridge Friends France: Racist Plutocrat Elected Meeting house, 5 Longfellow Park (10-minute walk from Harvard Square T station, west on Brattle St.), Cambridge. Many Oppose Sarkozy, but Weak and Divided — Agenda — by Doug Ireland, direland.typepad.com, 6 May 2007 Part I (6:50). Chapter business. Continuing discussion of N THE THIRD CONSECUTIVE DEFEAT FOR THE FRENCH LEFT in a priorities and projects Types and timing of working groups and presidential election, Nicolas Sarkozy has been chosen to general meetings. Leadership and roles...for you! Ilead France with a comfortable 53 percent of the vote, as the Part II (7:30): Video: The Great Turning, with David Korten. pre-election opinion polls had predicted. His Socialist opponent, PowerPoint and discussion—From Empire to Earth Community.