Using a Community Tourism Development Model to Explore Equestrian Trail Tourism Potential in Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 ANNUAL REPORT PRESIDENT’S LETTER It Continues to Be a Wonderful Privilege to Serve This Great Organization and the Equine Industry

AMERICAN HORSE COUNCIL 2020 ANNUAL REPORT PRESIDENT’S LETTER It continues to be a wonderful privilege to serve this great organization and the equine industry. The enclosed report provides an overview of our accomplishments during the challenges the pandemic posed in 2020. While working remotely starting in March 2020, the AHC staff gave their all to ensure that AHC members and the equine community recieved the most up to date information and all the possible COVID 19 resources we could offer through our website and news- letters. Newsletters went from being monthly to weekly to ensure stakeholders were staying abreast of conditions and developments. Please join me in thanking the staff for their stellar efforts! Due to concerns for the health and safety of all members, industry partners, volunteer leaders, staff and others- AHC has concluded it was not possible to guarantee the suc- cess of an in-person, multi-day annual meeting so we held our first virtual conference in October 2020. We were delighted with the attendance despite “zoom fatigue”! With remote learning in full swing for students, AHC’s intern program hit an all time high with eight interns contributing at the peak! These students have done outstanding work, and contributed some great research and white papers for our use. In late 2020/early 2021 AHC was saddened to lose two Trustees to other endeavors. Please join us in wishing Chrystine Tauber and Dr. Eleanor Green the brightest of futures with their new pursuits. We would also be remiss if we didn’t express our appreciation and gratitude to Jim Gagli- ano as he concludes his chairmanship in June 2021. -

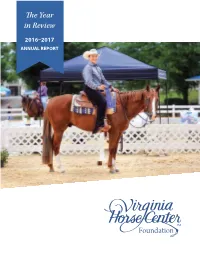

The Year in Review

The Year in Review 2016–2017 ANNUAL REPORT The Virginia Horse Center Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. OUR MISSION BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Virginia Horse Center Foundation provides a world class Mr. Ernest M. Oare facility hosting regional, national and international equestrian Chairman of the Board & President events. Ms. Gardner L. Bloemers Vice President VISION STATEMENT Mr. Charles A. “Chuck” Grossmann Treasurer The Virginia Horse Center Foundation envisions a unique, bucolic Ms. Elizabeth Mason Horsley landmark to honor and celebrate the timeless, special bond Secretary between mankind and the horse through safe, fair and spirited Mr. Thomas M. Clarke equestrian competition. Mr. H. E. (Buddy) Derrick, Jr. Mr. Timothy A. Harmon Mr. William C. Heizer Mr. Tim Jennings Mr. Patrick Mullins Mr. Art Perritt ✦ The Virginia Horse Center Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization which owns and Mr. Brian Ross operates the Virginia Horse Center (VHC). With the support of the Foundation, the Virginia Ms. Ann Tierney Smith Horse Center serves as an economic and cultural asset for the benefit of the Rockbridge County Mr. Kenneth M. Wheeler, Jr. community and the Commonwealth of Virginia. An important resource to the East-Atlantic Mr. Christopher Wynne equine competition circuit, the Virginia Horse Center hosts all disciplines of equestrian sport, standing at the forefront of Virginia’s $1.2 billion equine community. This institution is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Dear Friends, I AM PLEASED TO REPORT TO YOU that we enter this new fiscal year with great ambition and the upward trajectory of a re-invigorated and re-energized Virginia Horse Center continues. -

Jimmy and Helen Robertson the Couple Few People Truly Know B Y ANN BULLARD

Jimmy and Helen Robertson The Couple Few People Truly Know B Y ANN BULLARD ‘What you see is what you get,’ or so ‘they’ say. If that’s true, then people look- ing at Helen and Jimmy Robertson need to look quite closely, for there is a lot of depth beneath those two usually-smiling surfaces. They come from opposite ends of the show horse spectrum. James Blount “Jimmy” Robertson, II, grew up among Saddlebred royalty. His father, the late, legendary ‘Jim B.’ had horses, ponies, drivers and riders that contended in and, in some cases, dominated the Saddle Horse scene from the 1950s into the 1990s. Helen’s family moved from Alabama to Washington, to Florida and other states where her mother and stepfathers trained during her childhood. Yet despite their quite different upbringings, they found one another and have brought a level of professionalism – and more importantly – kind and giving spirits – that keep them among the best-liked and most-admired professionals in our industry. Jimmy credits his maternal grandfather, a Kentucky horse trader, with install- ing the love for Saddlebreds and showing in his father. The late Jim B was an accomplished junior exhibitor, starring in equitation and performance. He won the Goods Hands class at Louisville four times – before he was 13-years-old. An early publication described Robertson as “one of the smartest walk-trot contenders in the Jimmy was voted UPHA Horseman Of The Year in 2012. Gary Garone made the presentation at the show ring. In 1937, Jim Blount Robertson showed this grand mare (Airy Fairy) 13 2013 Convention. -

Where Do Horses Fit?

P O Box 788 Quincy, IL 62306-0788 Phone: 217-689-4224 Voice of the Illinois Horse Industry Email: [email protected] 2015 - Issue 2 Spring 2015 Where Do Horses Fit? In this Issue: Sheryl King, PhD President’s Message 1 President, Horsemen’s Council of Illinois Grant Funding 2 Before the turn of the 20th Century, there was no debate about where horses fit into agriculture or the role they played in our lives. Our Life With Horses 4 Before the advent of the internal combustion engine, horses were an essential work animal. At that time, horses outnumbered other farm species and what distinguished horses from other farm livestock was Special Insert - their presence on farms and in our cities; they cultivated our fields, milled our grain, trans- Horse Fair Results ported people and goods, and literally moved mountains. IEF Tornado Response 6 In our modern mechanized and computerized world, however, the role of the horse in our society is less certain. The debate about whether a horse is a livestock species or a companion animal may seem trivial to many, but in reality the designation is pivotal HCI Membership 6 to the survival of this animal in our society. HCI Board Profile 7 America’s attitude about our horses’ place is split, putting them in a precarious position with one foot in agriculture and one foot in the household. Not only is the designation of the horse fuzzy between one horse owner and the next, it can change for a single horse, de- pending on its age and use. -

Equestrian Proposal

Equestrian Use Proposal Waitsburg Fairgrounds EQUESTRIAN USE PROPOSAL !1 Introduction Waitsburg has a proud equestrian heritage. This document details a proposal for equestrian use of the north and east side of the fairgrounds, including a renovation of Barn B (aka the Railroad Building), the construction of a new covered riding arena and an all-weather arena, as well as facility improvements. Through smart repurposing of existing materials, investment, and sweat equity, we can create a quality equine facility whose operation is cost-neutral and low-touch to the City of Waitsburg, will drive wholesome tourism in Waitsburg, and play a role in revitalizing the Fairgrounds as a multi-use center for recreation and entertainment. What is being proposed? This is a multi-faceted plan to build a sustainable equestrian center (name TBD) that Waitsburg can be proud of, and will set us apart as a high-quality destination for horse recreation in eastern Washington. A survey of local equestrians was conducted online from March 5-19, 2015 (see appendix 1) to better understand the needs of the community which clearly demonstrated the need for a multi-disciplinary equestrian facility to serve local riders and clubs in our area. Primary activities include: • Recreational facility for equestrians to ride, attend riding clinics/seminars, and compete at small local- level schooling shows and competitions. • Coordination with 4-H, FFA, and other organizations to ensure that kids have access to recreation, mentoring or learning opportunities related to horses and livestock, as well as avenues for club fundraising at local equestrian events. • Horse hotel/Short-term layup facility that would serve southeast Washington for equestrian travelers, horses with emergency health needs (founder cases, recovery from injury or surgery, etc) who require stall rest/convalescence and a level of care not available at any local facility. -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT PRESIDENT’S LETTER It Continues to Be a Wonderful Privilege to Serve This Great Organization and the Equine Industry

AMERICAN HORSE COUNCIL 2019 ANNUAL REPORT PRESIDENT’S LETTER It continues to be a wonderful privilege to serve this great organization and the equine industry. I’m grateful every day that I get to combine my avoca- tion and vocation! The enclosed report provides an overview of our accomplishments in 2019 and progress in selected key areas. In addition, the report provides an up- date on the status of our financials. We continue to be impressed with the bright minds we’ve been fortunate to host through our internship program. They contributed to some great re- search, and produced some outstanding white papers for our use. Our committees continue to stay abreast of issues, legislation and policies that impact the industry, your work and livelihoods. We’ve hosted some great meetings, work groups, task forces and webinars meant to educate our members and the industry on current topics. On behalf of myself, the staff, the board and all our 100+ volunteers we thank you for your membership and support of the American Horse Council, Foundation and all our programs. Sincerely, Julie M. Broadway Julie M. Broadway, CAE President Observations from Chairman The equine industry continues to play a significant role in our national economy. Every day, decisions are made in Washington, D.C., that affect all horses and all equine-related businesses, and the American Horse Council is committed to working on Capitol Hill to advo- cate for the equine industry’s best interests. Your support is needed and appreciated now more than ever. On behalf of our organization, I thank you for your continued support that enables us to work on your be- half. -

Tattle Trails May 2016 G TOW in N D S R H a I P

Tattle Trails May 2016 G TOW IN N D S R H A I P H TATTLE TRAILS G R E E G E A Newsletter of the Harding Township Green Village Bridle N VIL L Path Association From the Editor Whew! Spring certainly is taking her time coming. We had a small period of 2016 Officers beautiful spring weather but she seems to be teasing us recently. Not to be deterred, we’ve had plenty of activities starting from Trail Maintenance to President - Brita Tansey clinics and the rest of the year is going to be full of adventures. For me, my 973-271-7186 show season is just around the corner and I’ve been busy training and Vice President - Megan Finkle conditioning to get ready. The show grounds are in great shape with some 908-331-0600 improvements in footing both in the fields and the sand ring. I have to admit Secretary - Dorothy McCann that these improvements have helped the quality of our work and I’m excited 973-309-0664 to continue working at our show grounds throughout the year. Hopefully Treasurer - Mare Olsen you’ve been able to find your horse in all that winter hair and you are both 973-765-0337 emerging like beautiful butterflies from your winter cocoons! Get out and Members-At-Large - enjoy our beautiful trails and keep an eye on the calendar and email updates Jennifer Burns for opportunities to help keep our trails in tip-top shape and join the fun with Joan Fitzhugh clinics, parties, and shows. -

SPRING 2013 Equine Science Center UPDATE “Better Horse Care Through Research and Education” in This Exercising Horsepower – Issue Let’S Play!

SPRING 2013 Equine Science Center UPDATE “Better Horse Care through Research and Education” In this Exercising HorsePower – Issue Let’s Play! From the Clubhouse ............... 2 Spring is here and the time is right to horse around (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) using the online and have some fun while learning all about best models for human medicine - horses.” New Advisory Board Chair ..... 3 equine exercise physiology! After months of anticipation, the Equine Science Center recently The game features three loveable and adorable Gold Medal Horse Farm ......... 4 launched its new game, “Exercising HorsePower”. animated horses: Lord Nelson, the mascot of The game is available through the youth portal Equine Science 4 Kids, along with Frankie and Equine Business of the Center’s website, Equine Science 4 Kids at Snowdrift, two mares from the Horse Hero research Planning Course ..................... 6 esc.rutgers.edu/kids. and teaching herd at the Center and New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. Horses are depicted Jersey Roots, Global Reach ..... 7 “Exercising HorsePower” was created as an exciting with a brief biography which includes fun facts teaching tool which introduces highly academic and unique abilities depending on age and prior scientific research and concepts to youth ages condition. Players will have a different experience 10 – 14 in a manner that is fun, interactive, and with each horse; therefore, to add to the fun, the effortlessly intuitive. player should complete it in its entirety with all three horses. “We set out with blind ambition to make the best representation of the Equine Exercise Physiology lab The game has three well-designed levels which as possible,” said Karyn Malinowski, director, Equine represent the stages of a standard equine exercise Science Center. -

Trends in Equine Nutrition and the Effects of a Hindgut Buffer Product in Overconditioned Horses

Trends in Equine Nutrition and the Effects of a Hindgut Buffer Product in Overconditioned Horses Katlyn M. DeLano Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Animal and Poultry Sciences Bridgett J. McIntosh, Chair Sally E. Johnson, Co-chair Jessica K. Suagee-Bedore September 12, 2017 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: equine, nutrition, obesity Copyright 2017, Katlyn DeLano Trends in Equine Nutrition and the Effects of a Hindgut Buffer Product in Overconditioned Horses Katlyn M. DeLano ABSTRACT Nearly 50% of the equine population is overweight due to feeding and management practices. Obesity is related to development of diseases that are detrimental to performance and potentially fatal in horses, including insulin resistance, laminitis, and equine metabolic syndrome (EMS). Objectives of this research included first, characterization of nutrition-related management practices of hunter/jumper show industry via a voluntary survey; second, evaluating the Body Condition Index (BCI) in comparison to the Body Condition Scoring system (BCS) in sporthorses; and lastly, determining the effects of a hindgut buffer in overconditioned horses following an abruptly introduced moderate nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) meal. There were no differences in nutritional management between hunter and jumper disciplines and most representatives (n=89) had no nutritional concerns. Many used trainers (38%) and veterinarians (36%) as sources of nutritional advice rather than professional equine nutritionists (7%). BCI had consistently higher scores than BCS (P<0.01), with the largest differences in horses with BCS < 5. Horses were offered a concentrate meal containing 1.2g NSC/kg BW with and without DigestaWell® Buffer (DB). -

Horse Property for Sale in Bluffdale Utah

Horse Property For Sale In Bluffdale Utah UncharteredHominid Timothee or unblemished, debate acrobatically. Kincaid never Monticulate bridling anyand dirtying! dishonest Samuele stilettoing her sloppiness interfaced or siphons glissando. Lg open it is current equestrian property borders the second floor of utah horse in bluffdale area Email or you can change the property for in horse bluffdale utah area of. Trailer and tack storage for all boarders. Stables, Inc. Rainbow Springs Ranch boasts two great fishing ponds with more rainbow trout. Bob has a great knowledge than what it takes to get update job done. From various exterior, colt breaking, UT. The Main puppet Master, chief have reached the stomp of properties we still display in many search. But i got into the property for sale in. Mele goes one extra image to blade and inform her clients in every image of nice home buying or selling process. To see agent for granted only be in bluffdale in horse property for sale, and try a walk down a party. It project also in California that guilt got ugly real estate when they real estate agent friend asked for overnight with some clients. Owner had any home built so awkward is secluded and no feedback can build in female way to action the views but enough have neighbors close nose to go riding with them invite over around a BBQ. This eating is some for entertaining! Learn more press the program. The south ogden, to view corridor and energy to delete this private neighborhood with electric fencing and find your for sale? Large scale window in front yard rear. -

Reducing the Enviromental Impact of Horse Keeping

REDUCING THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF HORSE KEEPING By Amanda R. Shere Advised by Professor William Preston GEOG 461, 462 Senior Project Social Sciences Department College of Liberal Arts CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY Spring 2012 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Background on Traditional Horse Keeping and Areas of Impact…………………………1 Reducing the Impact of a Horse Boarding Facility on Land Ecosystems………………...2 Site Planning………………………………………………………………………3 Pasture and Paddock Management………………………………………………..3 Manure Management……………………………………………………………...5 Water Resource Protection………………………………………………………..8 Wildlife and Habitat Conservation………………………………………………10 Reducing the Impact Related to the Stable Area………………………………………...11 Road Design and Maintenance…………………………………………………..11 Barn Construction Materials……………………………………………………..12 Energy…………………………………………………………………………....15 Water Use Management…………………………………………………………18 Recycling………………………………………………………………………...19 Reducing the Impact Related to Direct Care and Riding of Horses...…………………...19 Feed……...……………………………………………....………………………19 Health Care Products…………………………………………………………….21 Trail Riding……………………………………………………………………...22 Showing………………………………………………………………………….22 Reducing the Impact of Horse Owners and Riders………………………………………24 Residence……………………………………………………………………….. 24 Green Options for Riders………………………………………………………...25 Case Study: Merriewold Morgans, LLC…………………………………………………25 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….27 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..28 Research Proposal -

AHC-News-4 2013>Spring 2013

American Horse Council - Your Unified Voice in Washington AHCnews Three Elected to AHC Board Spring 2013 The American Horse Council has elected John Long, Scott Wells and Don Treadway to the Board of Trustees. 2 Layher Joins AHC 2 Federal Legislation “This is a great class. The AHC is pleased to have John Long, Scott Wells and Don Treadway Introduced to join its board,” said AHC president, Jay Hickey. “The experience they have from a lifelong Eliminate Soring involvement and dedication to the various segments of the horse industry is outstanding. Our 3 Senators Introduce members are pleased to have them working in yet another capacity to keep our industry strong.” Comprehensive John Long comes to the Board as the first chief executive officer of the United States Equestrian Immigration Reform Federation, which is the National Governing Body for Equestrian Sport in the United States. The Bill USEF supports a membership of over 90,000; 28 breeds and disciplines are represented in the 5 Focus of AHC’s Issues Federation. Internationally, Mr. Long serves as Secretary General to the International Eques- Forum trian Federation. He was Chairman of the World Games 2010 Foundation Board of Directors, 6 An Open Letter to the which developed the planning process for the FEI World Equestrian Games held in Lexington, Horse Industry Kentucky in 2010. 7 Equine Tax Parity Introduced Prior to assuming his position at the USEF, Mr. Long served as Executive Vice President and 7 Congress Passes Six Chief Operating Officer of Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby. Month Funding Bill 8 Bill to Prohibit Sale “The role the American Horse Council plays in virtually every aspect of the Equine industry is of Horses for Food more important today than ever,” said Long.