26Th Seaward Round, Central English Channel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithics, Landscape and People: Life Beyond the Monuments in Prehistoric Guernsey

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Archaeology Lithics, Landscape and People: Life Beyond the Monuments in Prehistoric Guernsey by Donovan William Hawley Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Archaeology Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lithics, Landscape and People: Life Beyond the Monuments in Prehistoric Guernsey Donovan William Hawley Although prehistoric megalithic monuments dominate the landscape of Guernsey, these have yielded little information concerning the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age communities who inhabited the island in a broader landscape and maritime context. For this thesis it was therefore considered timely to explore the alternative material culture resource of worked flint and stone archived in the Guernsey museum. Largely ignored in previous archaeological narratives on the island or considered as unreliable data, the argument made in this thesis is for lithics being an ideal resource that, when correctly interrogated, can inform us of past people’s actions in the landscape. In order to maximise the amount of obtainable data, the lithics were subjected to a wide ranging multi-method approach encompassing all stages of the châine opératoire from material acquisition to discard, along with a consideration of the landscape context from which the material was recovered. The methodology also incorporated the extensive corpus of lithic knowledge that has been built up on the adjacent French mainland, a resource largely passed over in previous Channel Island research. By employing this approach, previously unknown patterns of human occupation and activity on the island, and the extent and temporality of maritime connectivity between Guernsey and mainland areas has been revealed. -

School Trips to Normandy

SCHOOL TRIPS TO NORMANDY www.encotentin.fr COTENTIN, A PENINSULA OUT OF THE ORDINARY If you look at a map of France, you will see that Cotentin enjoys an exceptional situation. This is the only region on the French mainland where you can watch the sun rise, at daybreak, on the east coast… then on the same day, stand on the west coast from midday to see it start to set with the Channel Islands on the horizon. Between sunrise and sunset, there is an incredible catalogue of landscapes, shores, atmospheres, ambiances and horizons which can be explored with school groups. The tourist office wishes to better introduce you to this unknown and surprising land, surrounded on three sides by a secret sea and with a mysterious marsh completing the magic square. We want to help you spot the hidden treasures of this island-like region, a region out of the ordinary. Welcome to Cotentin! Let us make all the arrangements! Experts of this destination, we will be by your side before, during and after your stay. Our team is present all over Cotentin to offer bespoke programmes that cater to your every need in the best possible time. FOR A PERSONALISED ESTIMATE, PLEASE CONTACT : CÉCILE FOUCARD Tel: +33 (0)2 33 78 19 29 Mobile: +33 (0)6 85 82 67 48 www.encotentin.fr - [email protected] COTENTIN AND ENGLAND, A COMMON HISTORY The Cotentin peninsula is separated from England by a narrow sound we call « the English Channel » or « La Manche », depending on which side of the coast you stand. -

Le Programme Des Célébrations Vauban

Programme 5e anniversaire Patrimoine mondial Réseau des sites majeurs de Vauban 2013 www.sites-vauban.org « Vauban dépasse les bornes » En cette année 2013, le Réseau Vauban et ses 12 sites célèbrent le 5e anniversaire de l’inscription des fortifications de Vauban sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial . A cette occasion, l’ensemble des sites se mobilise autour d’une thématique commune Vauban dépasse les bornes , et vous propose une pro- grammation riche et variée pour vous faire décou- vrir leur patrimoine fortifié. Ce thème, s’il rappelle la raison d’être initiale de ces forteresses construites sur les limites du territoire, an- nonce avant tout la volonté d’ouverture de cette dyna- mique à l’ensemble des 12 territoires et à tous types de manifestations. Véritables supports pour des projets d’avenir , les fortifications de Vauban se dévoilent sous un jour nouveau, entre sport, nature et culture. BESANÇON Etendue de part et d’autre d’un méandre formé par le Doubs, Besançon occupe une place stratégique où Vauban perfectionne certains édifices et en conçoit de nouveaux remodelant ainsi entièrement la ville. Achevée en 1693 après 20 ans de travaux, murailles, tours bastionnées, quais, fossés et citadelle s’implan- tent aujourd’hui à merveille dans un paysage de collines forti- fiées, d’à-pics impressionnants et de mont boisés. Besançon tout entière est marquée de la signature du génie de Vauban. A voir / à faire La citadelle de Besançon est aujourd’hui devenue un haut lieu culturel et touristique. Au cœur des fortifications, venez décou- vrir le musée comtois, le Muséum d’histoire naturelle, le musée de la résistance et de la déportation et l’espace Vauban. -

The Vauban Fortifications of France Free

FREE THE VAUBAN FORTIFICATIONS OF FRANCE PDF Paddy Griffith,Peter Dennis | 64 pages | 25 Apr 2006 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781841768755 | English | United Kingdom The Vauban fortifications in France - Réseau des sites majeurs Vauban JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. You must have JavaScript enabled in your browser to utilize the functionality of this website. This website uses cookies to provide all of its features. By using our website you consent to all cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy. Enter your email address below to sign up to our General newsletter for updates from Osprey Publishing, Osprey Games and our parent company Bloomsbury. The Vauban Fortifications of France. Add to Basket. About this Product. Vauban was the foremost military engineer of France, not only during his lifetime, The Vauban Fortifications of France also throughout the 18th century when his legacy and methods remained in place almost unchanged. Indeed, his expertise and experience in the construction, defence, and attack of fortresses is unrivalled by any of his contemporaries, of any The Vauban Fortifications of France. In all three of those fields he The Vauban Fortifications of France a significant innovator and prolific exponent, having planned approximately major defensive projects and directed over 50 sieges. This book provides not only a modern listing of his varied interventions and their fates, but also a wide-ranging discussion of just how and why they pushed forward the international boundaries of the arts of fortification. Biographical Note. Paddy Griffith is a freelance military historian based in Manchester, working as both an author and a publisher. -

Dossier De Presse

BESANÇON FÊTE LE 10e ANNIVERSAIRE DE L’INSCRIPTION DE L’ŒUVRE DE VAUBAN AU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL DE L’UNESCO 7 juillet 2008 Québec - 7 juillet 2018 Besançon DOSSIER DE PRESSE #jaidixans SOMMAIRE COMMUNIQUÉ DE SYNTHÈSE 3 L’ŒUVRE DE VAUBAN À TRAVERS LES DOUZE SITES MAJEURS 4 LES CARACTÉRISTIQUES DE BESANÇON, TÊTE DE RÉSEAU 10 L’ÉVÈNEMENTIEL DES 10 ANS 12 LES TEMPS FORTS DE LA PROGRAMMATION 14 INTERVIEW DE JEAN-LOUIS FOUSSERET, MAIRE DE BESANCON, PRÉSIDENT DU RÉSEAU VAUBAN 17 « ILS FONT LE RÉSEAU VAUBAN » 18 CONTACT PRESSE Alexandra Cordier 03 81 61 52 25 / 06 42 27 67 89 [email protected] Crédits photos (sauf mention contraire) : Éric Chatelain, Jean-Charles Sexe – Ville de Besançon 2 COMMUNIQUÉ DE SYNTHESE Besançon, le 24/01/2018 Le 7 juillet 2008, douze sites fortifiés parmi les plus beaux réalisés par Vauban - Arras, Besançon, Blaye / Cussac-Fort- Médoc, Briançon, Camaret sur Mer, Longwy, Mont-Dauphin, Mont Louis, Neuf-Brisach, Saint-Martin-de-Ré, Saint-Vaast-la- Hougue, Villefranche-de-Conflent - sont inscrits sur la Liste du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO. Ce patrimoine militaire, unique en Europe, est le premier bien en série en France à rejoindre la Liste. Chaque site représente une facette des fortifications de Vauban, formant ainsi une déclinaison complète et exemplaire de l’œuvre de défense du grand ingénieur et exprimant la valeur universelle de son œuvre. Cette année, Besançon et les douze sites fédérés au sein du réseau Vauban, l’association qui a porté le projet et fédère les douze places fortes, fêtent les 10 ans de l’inscription de l’œuvre de Vauban au patrimoine mondial. -

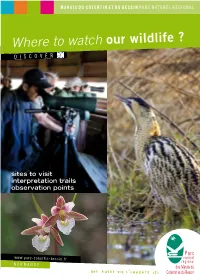

Where to Watch Our Wildlife ? D I S C O V E R

MARAIS DU COTENTIN ET DU BESSIN PARC NATUREL RÉGIONAL Where to watch our wildlife ? D I S C O V E R sites to visit interpretation trails observation points www.parc-cotentin-bessin.fr N O R M A N D Y PARC NATUREL RÉGIONAL DES MARAIS DU COTENTIN ET DU BESSIN Environment and landscapes Marshlands CHERBOURG-OCTEVILLE Introduction Foreshore BARFLEUR 1 The Mont de Doville p. 3 FieldsF and hedgerows QUETTEHOU 2 The Havre at Saint-Germain-sur-Ay p. 4 CHERBOURG-OCTEVILLE 3 Mathon peat bog p. 6 CHERBOURG-OCTEVILLE Moor 4 The Lande du Camp p. 7 D 14 Wood or forest 5 Saint-Patrice-de-Claids heaths p. 8 La Sinope VALOGNES 6 Sursat pond p. 9 SNCF Dune oro beach N 13 D 42 7 Rouges-Pièces reedbed p. 10 D 24 MONTEBOURG 8 p. 11 BRICQUEBEC Bohons Reserve Le Merderet 16 D 42 Marshlands, 9 D 14 D 421 The Port des Planques p. 12 between two coastlines… N 13 La Douve 18 D 15 10 D 900 The Château de la Rivière p. 13 11 The Claies de Vire p. 14 D 2 STE-MÈRE- 12 19 ÉGLISE The Aure marshes p. 15 ST-SAUVEUR- LE-VICOMTE D 15 Chef-du-Pont D 913 17 13 The Colombières countryside p. 16 D 70 Baie D 514 BARNEVILLE- des Veys D 15 La Douve D 70 CARTERET Les Moitiers- 14 The Ponts d’Ouve “Espace Naturel Sensible” p. 17 Le Gorget en-Bauptois D 113 20 La Senelle 15 15 The Veys bay p. -

Les Sites UNESCO De Vauban

VAUBAN L’intelligence du territoire Portfolio des sites candidats à l’UNESCO Portfolio des sites candidats à l’Unesco Le 5 janvier 2007, le gouvernement français a décidé de proposer à l’Unesco l’inscription de l’œuvre de Vauban Lau Patrimoine mondial de l’humanité. Un comité scientifique a retenu une série de sites qui illustre les facettes de l’œuvre architecturale de Vauban : remaniement d’ouvrages existants, adaptation au terrain (mer, montagne, plaine, rivière), diversité des réalisations (enceinte urbaine, citadelle, fort, tours, ville neuve, inondation défensive), places fortes des trois « systèmes » de Vauban. À ces critères de choix se sont ajoutés l’état de conservation, l’authenticité et les politiques de mise en valeur et de protection. C’est à partir d’une grille d’analyse de tous ces éléments qu’ont été choisis Arras, Besançon, l’ensemble citadelle de Blaye – Cussac-Fort-Médoc, Briançon, Camaret-sur-Mer, la citadelle du Palais à Belle-Île-en-Mer, Longwy, Mont-Dauphin, Mont-Louis, Neuf-Brisach, Saint-Martin-de-Ré, Saint-Vaast-La-Hougue et Villefranche-de-Conflent. Le château de Bazoches a été retenu pour avoir été la villégiature de Vauban depuis 1679 et surtout son bureau d’études, où travaillaient ingénieurs, dessinateurs et secrétaires. Ces sites sont illustrés dans les pages qui suivent par des vues aériennes (© Franck Lechenet ; sauf Arras © Pascal Lemaître et Besançon © J.-P. Tupin – ville de Besançon) sur lesquelles les tracés en étoile des fortifications bastionnées sont toujours lisibles. En regard, un document, plan ou élévation, dessiné par un successeur de Vauban, montre l’état des travaux quarante ou cinquante années après les premiers projets de l’ingénieur. -

AREA No. 1 Pas-De-Calais Capes and Strait of Dover

AREA no. 1 Pas-de-Calais Capes and Strait of Dover Vocation: Prevalence of maritime shipping, challenges with maritime curityse and port infrastructure and marine renewable energy. The need to sustain marine fishing activity, the zone’s aquaculture potential, as well as marine aggregates, while at the same time allowing growing tourism activity. Safeguarding migration corridors and key habitats. Illustrative map of the major ecological and socioeconomic issues I. Presentation of the zone Associated ecological area: Sector 1: Southern North Sea and Strait of Dover Area 2: Picardy Estuaries and the Opal Sea Associated water mass: FRAC01 BELGIAN BORDER TO THE MALO BREAKWATERS FRAC02 MALO BREAKWATERS TO THE EAST OF GRIS NEZ CAPE FRAC03 GRIS NEZ CAPE TO SLACK FRAT02 PORT OF BOULOGNE FRAT03 PORT OF CALAIS FRAT04 PORT OF DUNKIRK AND INTERTIDAL ZONE TO THE BREAKWATER Broadly, in terms of identified ecological challenges, the Strait of Dover is a bottleneck where the North Sea and the English Channel meet. This ecological unit has particular hydrographic conditions; there are many sandbanks in the area, including subaqueous dunes formed by swells and currents. The poorly sorted sands on the coastal fringe are characterised by high densities of invertebrates, including molluscs and bivalves. As an area of high plankton production, this productive environment provides an abundant and diversified food supply for epifauna and forage species. As well as being an important feeding area for top predators, the strait also has a high concentration of cod, is a nursery area for whiting, plaice and sole and a spawning area for herring. Porpoises concentrate in the area during winter due to the abundance of prey species and the sandbanks are popular resting places for grey seals (the largest colony in France). -

Vauban's Iron Belt Stars, Protection of the Hexagon 11 June 2020 Sentinel-2 MSI Acquired on 15 October 2017 at 10:40:09 UTC

Sentinel Vision EVT-675 Vauban's iron belt stars, protection of the hexagon 11 June 2020 Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 15 October 2017 at 10:40:09 UTC ... Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 04 April 2020 at 17:40:55 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 18 May 2020 at 10:56:19 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Urban planning, security, river, sea, island, hill, mountain, plain, France Fig. 1 - S2 (18.05.2020) - Vauban Citadel in Arras was built after the conquest of the city in 1659. The citadel was built as part of the 2nd line of the "pré carré". It has been nicknamed La belle inutile, the beautiful useless one. 2D view Easily recognized from space, the fortifications designed by Vauban 300 to 350 years ago are spread along all French borders. Their historical significance has been recognised by UNESCO in 2008 when 12 of such sites accessed the World Heritage status: "Fortifications of Vauban consists of 12 groups of fortified buildings and sites along the western, northern and eastern borders of France. They represent the finest examples of the work of Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707), a military engineer of King Louis XIV. The serial property includes towns built from scratch by Vauban, citadels, urban bastion walls and bastion towers. There are also mountain forts, sea forts, a mountain battery and two mountain communication structures. The work of Vauban constitutes a major contribution to universal military architecture. It crystallises earlier strategic theories into a rational system of fortifications based on a concrete relationship to territory. -

English Channel

PUB. 191 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ ENGLISH CHANNEL ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Bethesda, Maryland © COPYRIGHT 2006 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2006 TWELFTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 Preface 0.0 Pub. 191, Sailing Directions (Enroute) English Channel, 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same Twelfth Edition, 2006, is issued for use in conjunction with manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a Pub. 140, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) North Atlantic course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of Ocean, Baltic Sea, North Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea. origin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the Companion volumes are Pubs. 192, 193, 194, and 195. designated course. Vessels following the directives must allow for every influence tending to cause deviation from such track, 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 9 September 2006, and navigate so that the designated course is continuously including Notice to Mariners No. 36 of 2006. being made good. 0.0 Currents.—Current directions are the true directions toward Explanatory Remarks which currents set. 0.0 Dangers.—As a rule outer dangers are fully described, but 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- inner dangers which are well-charted are, for the most part, Intelligence Agency (NGA), under the authority of Department omitted. -

Group Travel Discover La Manche, the Normandy Peninsula

group Travel Discover la Manche, the Normandy Peninsula... Mont Saint-Michel and its bay © Marc Lerouge - CDT50 Poole Cherbourg Deauville Saint-Lô Caen Granville NORMANDY Mont Saint-Michel By ferry From Great-Britain and Ireland Poole to Cherbourg / Brittany Ferries Portsmouth to Cherbourg / Brittany Ferries access... Rosslare to Cherbourg / Irish Ferries & Stenaline Dublin to Cherbourg / Irish Ferries From the Channel islands (Manche Îles Express) By road Jersey, Guernsey, Sark (via Jersey) to Granville La Manche is served by two motorways: Jersey to Carteret the A13 coming from Paris and the A84 serving Guernsey, Alderney to Diélette the whole of the west of France. By plane to Saint-Lô By train Paris Roissy CDG + train: 330 km / 205 miles Paris - Cherbourg / Saint-Lazare station Nantes Atlantique + train: 270 km / 167 miles Paris - Granville / Montparnasse station Rennes Saint-Jacques + train: 160 km / 99 miles Paris - Rennes (TGV) with a bus transfer Caen-Carpiquet + train: 70 km / 43 miles from Rennes to Mont Saint-Michel Cherbourg-Maupertus (aerodrome) + train: 80 km/49 miles facts listings & figures... & labels... Surface area 2 sites are listed as UNESCO world heritage sites: Mont Saint-Michel and its Bay, the Vauban towers of Hougue 5 938 km² and Tatihou in Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue (east of Cherbourg). 6 ISLANDS 2 «Towns of Art and History»: Coutances and the Clos du Cotentin Mont Saint-Michel, Tombelaine, Chausey, (around Bricquebec, St-Sauveur-le-Vicomte and Valognes). Tatihou, Îles Saint-Marcouf, Île Pelee. 1 «City Applied Arts»: Villedieu-les-Poêles. Length Width 1 «Loveliest Villages in France»: Barfleur (east of Cherbourg). -

Fortifications De Vauban À Besançon Comprennent La Citadelle Et Deux Enceintes Urbaines (Boucle Et Battant)

FortificationsFortifications dede VaubanVauban EsquisseEsquisse dede mmééthodethode dede spatialisationspatialisation dede lala VUEVUE dd’’unun bienbien enen sséérierie :: anticiperanticiper lala questionquestion desdes ééoliennesoliennes AlineRSMV Le –Cœur Éoliennes et Marieke/ Patrimoine Steenbergen mondial, 25/01/17 DouzeDouze fortificationsfortifications dede VaubanVauban sélectionnées parmi 160 selon 4 critères • Etat de conservation, intégrité, authenticité • Catégories : • Création / adaptation • Typologie géographique • Typologie d’ouvrages: ville neuve, forts détachés, enceintes urbaines, citadelles, tours • 1er, 2e et 3e système RSMV – Éoliennes / Patrimoine mondial, 25/01/17 Mont‐Louis Tatihou Villefranche‐ RSMV – Éoliennes / Patrimoine mondial, 25/01/17 Blaye de‐Conflent Mont‐Dauphin Camaret‐sur‐Mer RSMV – Éoliennes / Patrimoine mondial, 25/01/17 Arras Longwy Besançon Briançon NeufRSMV‐Brisach – Éoliennes / Patrimoine mondial,Saint 25/01/17‐Martin‐de‐Ré LaLa DVUEDVUE dede 20082008 L'œuvre de Vauban constitue une contribution majeure à l'architecture militaire universelle. Elle cristallise les théories stratégiques antérieures en un SYSTÈME DE FORTIFICATIONS RATIONNEL BASÉ SUR UN RAPPORT CONCRET AU TERRITOIRE. Elle témoigne de l'évolution de la fortification européenne au XVIIe siècle et a produit des modèles employés dans le monde entier jusqu'au milieu du XIXe siècle, en illustrant une période significative de l'histoire. Critère (i) : Les réalisations de Vauban témoignent de L'APOGÉE DE LA FORTIFICATION BASTIONNÉE CLASSIQUE, TYPIQUE DE L'ARCHITECTURE MILITAIRE OCCIDENTALE DES TEMPS MODERNES. Critère (ii) : La Part de Vauban dans l'histoire de la fortification est majeure. L'imitation de ses modèles‐types de bâtiments militaires en Europe et sur le continent américain, la diffusion en russe et en turc de sa pensée théorique comme l'utilisation des formes de sa fortification en tant que modèle pour des forteresses d'Extrême‐Orient, témoignent de l'universalité de son œuvre.