Homelessness in Echuca Moama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View More Samplers Click Here

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently New South Wales Almanac and Country Directory 1924 Ref. AU2115-1924 ISBN: 978 1 74222 770 2 This book was kindly loaned to Archive Digital Books Australasia by the University of Queensland Library www.library.uq.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

Murrumbidgee Regional Fact Sheet

Murrumbidgee region Overview The Murrumbidgee region is home The river and national parks provide to about 550,000 people and covers ideal spots for swimming, fishing, 84,000 km2 – 8% of the Murray– bushwalking, camping and bird Darling Basin. watching. Dryland cropping, grazing and The Murrumbidgee River provides irrigated agriculture are important a critical water supply to several industries, with 42% of NSW grapes regional centres and towns including and 50% of Australia’s rice grown in Canberra, Gundagai, Wagga Wagga, the region. Narrandera, Leeton, Griffith, Hay and Balranald. The region’s villages Chicken production employs such as Goolgowi, Merriwagga and 350 people in the area, aquaculture Carrathool use aquifers and deep allows the production of Murray bores as their potable supply. cod and cotton has also been grown since 2010. Image: Murrumbidgee River at Wagga Wagga, NSW Carnarvon N.P. r e v i r e R iv e R v i o g N re r r e a v i W R o l g n Augathella a L r e v i R d r a W Chesterton Range N.P. Charleville Mitchell Morven Roma Cheepie Miles River Chinchilla amine Cond Condamine k e e r r ve C i R l M e a nn a h lo Dalby c r a Surat a B e n e o B a Wyandra R Tara i v e r QUEENSLAND Brisbane Toowoomba Moonie Thrushton er National e Riv ooni Park M k Beardmore Reservoir Millmerran e r e ve r i R C ir e e St George W n i Allora b e Bollon N r e Jack Taylor Weir iv R Cunnamulla e n n N lo k a e B Warwick e r C Inglewood a l a l l a g n u Coolmunda Reservoir M N acintyre River Goondiwindi 25 Dirranbandi M Stanthorpe 0 50 Currawinya N.P. -

Travel to the Murray Year Ended June 2017 for the Period of July 2016 to June 2017

Travel to The Murray Year ended June 2017 For the period of July 2016 to June 2017 Sources: (1) National Visitor Survey (NVS) & (2) International Visitor Survey (IVS), YE Jun 17, Tourism Research Australia (TRA) - unless otherwise specified. Domestic Overnight Travel1 Visitors and nights Origin YE Jun 13 YE Jun 14 YE Jun 15 YE Jun 16 YE Jun 17 Share of visitors Share of nights 3,500 Origin YE Jun 16 YE Jun 17 YE Jun 16 YE Jun 17 Regional NSW 17.7% 23.7% 15.0% 19.9% 3,000 Sydney 9.0% 11.0% 8.2% 10.8% 2,892 2,898 Total intrastate 26.7% 34.6% 23.2% 30.8% 2,500 2,606 2,670 2,375 Victoria 58.9% 53.9% 57.3% 58.0% 2,000 South Australia 4.6% 4.1% 5.2% 3.5% Queensland 5.4% 3.1% 7.8% 4.7% 1,500 Other interstate 4.4% 4.3% 6.6% 3.0% Total interstate 73.3% 65.4% 76.8% 69.2% 1,000 1,091 1,108 964 953 995 Victoria (53.9%) was the largest source of visitors to the region, 500 followed by regional NSW (23.7%) and Sydney (11.0%). Compared to YE Jun 16, the regional NSW source market grew by 0 Visitors ('000) Nights ('000) 35.6%* and Sydney increased by 23.6%. Over the same period, Victoria declined by 7.2% and South Australia decreased by 9.1% The Murray received over 1.1 million domestic overnight visitors while Queensland fell by 41.0%. -

The Deniliquin & Moama Railway Company

The Deniliquin & Moama Railway Company Pastoral Times reported. When paddle steamers first reached Echuca in 1853, The following year the recently-formed Murray and they travelled up from South Australia with the Darling River Railway Association again petitioned for a intention of delivering goods from that state to the light railway between Deniliquin and Moama. It was Echuca region and taking back wool from the given the green light bya select committee of the New Riverina sheep stations. South Wales parliament but according to the Pastoral The Victorian government reacted by building a rail- Times was rejected in the Legislative Assembly (the way line, which was already being constructed to the upper house) “by an overwhelming majority”, Castlemaine and Bendigo goldfields, to the Murray. apparently on the assurance of Sir James Martin who told the members that “two drays a week would It reached the river port in 1863 and was supply Deniliquin with all its requirements” and that immediately successful in stemming the flow of trade “only a few townspeople who wanted to sell out were to the bottom end of the river. getting up the agitation that the country people However for the people of Deniliquin it was nothing around Deniliquin had no sympathy with it.” More more than a tantalising glimpse of the benefits of a lobbying followed. Contrary to Sir James Martin's new technology. They were serviced by Cobb & Co assertion, freight charges were crippling the local coach, the fare for which, to Echuca, was greater than economy. Just before the railway arrived the cost of the rail fare from there to Melbourne. -

Markets Local Produce

sauvignon and chardonnay. and sauvignon chardonnay. and sauvignon each year, the region is best known for its shiraz, cabernet cabernet shiraz, its for known best is region the year, each cabernet shiraz, its for known best is region the year, each With more than 80 hectares of vines flourishing with new growth growth new with flourishing vines of hectares 80 than more With growth new with flourishing vines of hectares 80 than more With By appointment weekdays appointment By weekdays appointment By & public holidays public & holidays public & 5482 1407 5482 5482 1407 5482 Open most weekends most Open Open most weekends most Open 23 Meninya St, Moama St, Meninya 23 23 Meninya St, Moama St, Meninya 23 5480 9983 5480 5480 9983 5480 Noel’s Quality Meats Quality Noel’s Noel’s Quality Meats Quality Noel’s Moama Moama Nov-Dec subject to avail. to subject Nov-Dec Nov-Dec subject to avail. to subject Nov-Dec 144 Old Deniliquin Rd, Rd, Deniliquin Old 144 144 Old Deniliquin Rd, Rd, Deniliquin Old 144 5480 9820 5480 5480 9820 5480 The Yabby Men Yabby The The Yabby Men Yabby The Connect with us with Connect Connect with us with Connect Moama (9km) Moama Moama (9km) Moama 0414 555 044 555 0414 0414 555 044 555 0414 67 Mayfield Crt, Crt, Mayfield 67 67 Mayfield Crt, Crt, Mayfield 67 [email protected] [email protected] Echuca Village Echuca Echuca Village Echuca Cherries Cherries 03 5480 7555 or Freecall 1800 804 446 804 1800 Freecall or 7555 5480 03 03 5480 7555 or Freecall 1800 804 446 804 1800 Freecall or 7555 5480 03 359 Lady Augusta Rd, Rd, -

Murray Football League Reserves Finals

MURRAY FOOTBALL LEAGUE RESERVES FINALS 1959 Numurkah v Cobram Nathalia v Finley Numurkah v Finley NUMURKAH v Nathalia 1960 Numurkah v Finley Cobram v Deniliquin Deniliquin v Numurkah COBRAM v Deniliquin 1961 Deniliquin v Finley Cobram v Numurkah Numurkah v Deniliquin NUMURKAH v Cobram 1962 Cobram v Blighty Deniliquin v Numurkah Numurkah v Cobram DENILIQUIN v Numurkah 1963 Deniliquin v Cobram Numurkah v Strathmerton Strathmerton v Deniliquin NUMURKAH v Strathmerton 1964 Deniliquin v Cobram Numurkah v Finley Deniliquin v Finley NUMURKAH v Deniliquin 1965 Berrigan v Tocumwal Deniliquin v Numurkah Numurkah v Berrigan NUMURKAH v Deniliquin 1966 Berrigan v Cobram Finley v Numurkah Finley v Berrigan BERRIGAN v Numurkah 1967 Cobram v Berrigan Deniliquin v Finley Finley v Cobram DENILIQUIN v Finley 1968 Nathalia v Berrigan Cobram v Tocumwal Cobram v Nathalia COBRAM v Tocumwal 1969 Cobram v Finley Tocumwal v Berrigan Berrigan v Cobram TOCUMWAL v Berrigan 1970 Berrigan v Deniliquin Numurkah v Tocumwal Tocumwal v Berrigan TOCUMWAL v Numurkah 1971 Finley v Numurkah Tocumwal v Deniliquin Deniliquin v Finley TOCUMWAL v Deniliquin 1972 Cobram v Finley Numurkah v Deniliquin Cobram v Deniliquin DENILIQUIN v Numurkah 1973 Numurkah v Tocumwal Deniliquin v Cobram Cobram v Numurkah DENILIQUIN v Cobram 1974 Strathmerton v Finley Deniliquin v Cobram Strathmerton v Cobram STRATHMERTON v Deniliquin 1975 Finley v Berrigan Deniliquin v Strathmerton Strathmerton v Finley DENILIQUIN v Strathmerton 1976 Strathmerton v Berrigan Cobram v Deniliquin Cobram v Strathmerton -

NSW Trainlink Regional Train and Coach Services Connect More Than 365 Destinations in NSW, ACT, Victoria and Queensland

Go directly to the timetable Dubbo Tomingley Peak Hill Alectown Central West Euabalong West Condobolin Parkes Orange Town Forbes Euabalong Bathurst Cudal Central Tablelands Lake Cargelligo Canowindra Sydney (Central) Tullibigeal Campbelltown Ungarie Wollongong Cowra Mittagong Lower West Grenfell Dapto West Wyalong Bowral BurrawangRobertson Koorawatha Albion Park Wyalong Moss Vale Bendick Murrell Barmedman Southern Tablelands Illawarra Bundanoon Young Exeter Goulburn Harden Yass Junction Gunning Griffith Yenda Binya BarellanArdlethanBeckomAriah Park Temora Stockinbingal Wallendbeen Leeton Town Cootamundra Galong Sunraysia Yanco BinalongBowning Yass Town ACT Tarago Muttama Harden Town TASMAN SEA Whitton BurongaEuston BalranaldHay Carrathool Darlington Leeton NarranderaGrong GrongMatong Ganmain Coolamon Junee Coolac Murrumbateman turnoff Point Canberra Queanbeyan Gundagai Bungendore Jervis Bay Mildura Canberra Civic Tumut Queanbeyan Bus Interchange NEW SOUTH WALES Tumblong Adelong Robinvale Jerilderie Urana Lockhart Wagga Wondalga Canberra John James Hospital Wagga Batlow VICTORIA Deniliquin Blighty Finley Berrigan Riverina Canberra Hospital The Rock Laurel Hill Batemans Bay NEW SOUTH WALES Michelago Mathoura Tocumwal Henty Tumbarumba MulwalaCorowa Howlong Culcairn Snowy Mountains South Coast Moama Barooga Bredbo Albury Echuca South West Slopes Cooma Wangaratta Berridale Cobram Nimmitabel Bemboka Yarrawonga Benalla Jindabyne Bega Dalgety Wolumla Merimbula VICTORIA Bibbenluke Pambula Seymour Bombala Eden Twofold Bay Broadmeadows Melbourne (Southern Cross) Port Phillip Bay BASS STRAIT Effective from 25 October 2020 Copyright © 2020 Transport for NSW Your Regional train and coach timetable NSW TrainLink Regional train and coach services connect more than 365 destinations in NSW, ACT, Victoria and Queensland. How to use this timetable This timetable provides a snapshot of service information in 24-hour time (e.g. 5am = 05:00, 5pm = 17:00). Information contained in this timetable is subject to change without notice. -

Section 2 As A4

Murray Mouth and Coorong 4B Big Bend near Nildotte 2B Morgan Wharf, Morgan 2B Lock 11, Mildura 2F Thompson’s Beach, Cobram K5 Cosmopolitan Albury 5L Hume Dam, Albury Wodonga 5M Wooden Boat Festival - Goolwa 4A Murray Princess Purnong 3B Banrock Station, Kingston-on-Murray 2C Houseboating at Headings Cliffs, Murtho 1D Riverside camping in Robinvale Euston 2G Echuca Wharf, Echuca Moama 5I Lake Mulwala on dusk, Yarrawonga 5K Views to the Kosciuszko National Park 6N To protect Australia’s horticultural industry, there are restrictions about which fruit and vegetables you can take into the Fruit Fly Exclusion Zone, the Greater Sunraysia Pest Free Area, Riverina Production Areas and across state borders. You may not enter these areas or cross state borders with tropical and temperate fruits (including mangos, avocados, grapes and berries), pome fruits (such as apples, pears and quince), citrus fruits, stone fruits (including apricots and peaches) and fruiting vegetables (capiscums, chillies, eggplants, tomatoes and tamarillos). There are disposal bins for unwanted fruit and vegetables on major transport routes. On the spot fines apply and they can go as high as $20,000. So do the right thing – eat up or dispose of produce in the bins provided and keep your money for your Murray holiday! Visit murrayriver.com.au/fruit-fly-free-zone These tips are provided to assist with safety and enjoyment of your travels through the Murray region. Some parts of the Murray are quite remote so taking precautions for travelling is strongly advisable. The tips below are also for most Australian driving and travelling conditions. -

Murray Valley Regional and National Parks Gulpa Island, Millewa & Moira Precincts (Formerly State Forest)

Murray Valley Regional and National Parks Gulpa Island, Millewa & Moira Precincts (formerly State Forest) www.parkweb.vic.gov.au phone 131 963 LEGEND Unsealed Road - On Park Unsealed Road - Off Park Dry weather forest drive Sealed Road Accredited visitor information centre Accommodation, caravan park Camping, bushwalking Barbeque, picnic table Swimming, canoeing Dog walking, petrol To Kerang Toilets, toilets for the disabled Rubbish Collection site MURRAY VALLEY HWY Cobram Proposed HWY VALLEY GOULBURN Murray Boat ramp River Park Golf, bowling Yarrawonga River Copyright Office of Environment and Heritage, July 2011. Moama To Echuca Moama 14km To Perricoota State Forest, & Perricoota Wine District These maps give you a basic overview of features and National Park facilities. They do not provide detailed information on Echuca topography and landscape, and may not be suitable for some activities. We recommend that you buy a Regional Park topographic map before you go exploring. Visitors should Victorian National Park check availability and booking of facilities. Digital data To Melbourne To Melbourne To Melbourne used with the permission of Parks Victoria. FreQUentlY ASKed QUestions Do I need to pay any fees to enter the new parks? No, there are no entry fees. What activities can I do in the national and regional parks? You are welcome to do the following activities: • camping • enjoy a picnic or a barbecue • swimming, boating or canoeing • bushwalking and orienteering • scenic forest drives • cycling • fishing • bird watching and photography Can I bring my dog to the parks? Dogs are allowed in all regional parks. You can take your dog for a walk or camping. -

MURRAY FOOTBALL LEAGUE UNDER 14’S FINALS

MURRAY FOOTBALL LEAGUE UNDER 14’s FINALS 1977 Deniliquin v Cobram Finley v Tocumwal Deniliquin v Tocumwal FINLEY v Deniliquin 1978 Numurkah v Deniliquin Cobram v Finley Finley v Numurkah COBRAM v Finley 1979 Finley v Jerilderie Cobram v Deniliquin Deniliquin v Finley COBRAM v Deniliquin 1980 Cobram v Deniliquin Finley v Jerilderie Finley v Cobram JERILDERIE v Cobram 1981 Jerilderie v Finley Nathalia v Deniliquin Deniliquin v Jerilderie Nathalia v Cobram Deniliquin v Cobram DENILIQUIN v Nathalia 1982 Deniliquin v Numurkah Finley v Berrigan Finley v Cobram Cobram v Deniliquin COBRAM v Finley 1983 Deniliquin v Berrigan Cobram v Numurkah Deniliquin v Numurkah Cobram v Finley Finley v Deniliquin COBRAM v Deniliquin 1984 Deniliquin v Numurkah Finley v Nathalia Nathalia v Deniliquin Cobram v Finley Finley v Deniliquin COBRAM v Finley 1985 Tocumwal v Numurkah Finley v Deniliquin Deniliquin v Tocumwal Cobram v Finley Finley v Deniliquin COBRAM v Finley 1986 Finley v Tocumwal Cobram v Deniliquin Finley v Deniliquin Cobram v Berrigan Finley v Berrigan COBRAM v Finley 1987 Berrigan v Numurkah Deniliquin v Jerilderie Jerilderie v Berrigan Cobram v Deniliquin Deniliquin v Berrigan COBRAM v Deniliquin 1988 Numurkah v Tocumwal Cobram v Finley Finley v Tocumwal Deniliquin v Cobram Cobram v Finley COBRAM v Deniliquin 1989 Mulwala v Tocumwal Barooga v Finley Finley v Mulwala Numurkah v Barooga Numurkah v Finley FINLEY v Barooga 1990 Cobram v Berrigan Numurkah v Deniliquin Cobram v Deniliquin Mulwala v Numurkah Mulwala v Deniliquin NUMURKAH v Deniliquin -

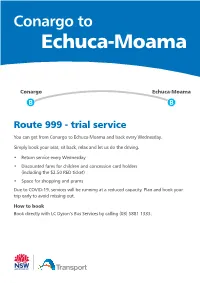

Echuca-Moama

Conargo to Echuca-Moama Conargo Echuca-Moama Route 999 - trial service You can get from Conargo to Echuca-Moama and back every Wednesday. Simply book your seat, sit back, relax and let us do the driving. • Return service every Wednesday • Discounted fares for children and concession card holders (including the $2.50 RED ticket) • Space for shopping and prams Due to COVID-19, services will be running at a reduced capacity. Plan and book your trip early to avoid missing out. How to book Book directly with LC Dyson’s Bus Services by calling (03) 5881 1333. Service timetable Conargo The trial service runs from Conargo to Echuca-Moama every Wednesday. Deniliquin Mathoura Echuca-Moama Conargo to Echuca-Moama Echuca-Moama to Conargo Wednesday Wednesday Opposite Conargo Junction Store Echuca Regional Health – Service St 08:25 14:00 Conargo Rd (stop is out the front of Echuca Health) Deniliquin North Information Bay 08:50 Echuca Railway Station 14:05 Service Rd off Davidson St Whitelock St Bus Interchange V/Line stop – Whitelock St opp Gorman Park 08:55 Moama coach stop – V/Line bus stop 14:10 (Stop ID 271028) Mathoura V/Line stop (opposite Caltex) Boundary Rd (Meninya St), Moama – 09:25 14:13 corner Cobb Hwy and Lawrence St (Stop ID 273110) Central Motel Moama – corner Meninya Mathoura V/Line stop – (in front of 09:55 14:45 St (Cobb Hwy) and Maiden St Caltex) corner Cobb Hwy and Lawrence St Whitelock St, coach stop – Deniliquin Moama coach stop – VLine bus stop 10:00 15:15 coach stop, Whitelock St (Stop ID 27101) Deniliquin Information Bay Echuca Railway Station 10:05 15:20 Service Rd off Davidson St Echuca Regional Health – Service St Conargo Junction Store 10:10 15:45 (stop is out the front of Echuca Health) corner Conargo Rd and Carrathool Rd For more information and to plan your trip, Limited time trial. -

Wakool Shire Development Control Plan 2013

Wakool Development Control Plan 2013 WAKOOL SHIRE DEVELOPMENT CONTROL PLAN 2013 OCTOBER 2013 Wakool Shire Council Amendment 1: August 2014. Amendment 2: April 2015 Development Control Plan 2013 Page 1 Wakool Development Control Plan 2013 This DCP was prepared by iPLAN PROJECTS (Orange NSW) in association with Wakool Shire Council. The team would like to thank everyone who was involved with this project or provided feedback. This DCP has also been based on a literature review and some wording of controls from other successful DCPs across NSW so Wakool Shire Council thanks those other Councils for their assistance. Wakool Shire Council Amendment 1: August 2014. Amendment 2: April 2015 Development Control Plan 2013 Page 2 Wakool Development Control Plan 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS A INTRODUCTION A.1 HOW TO USE THIS DCP A.1.1 WHERE DOES THIS DCP APPLY A.1.2 WHEN DOES THIS DCP COMMENCE A.1.3 PURPOSE OF THIS DCP A.1.4 AIMS OF THE DCP A.1.5 HOW TO READ THIS DCP A.1.6 HOW TO ADDRESS THE CONTROLS IN THIS DCP A.1.7 VARIATIONS TO THE CONTROLS IN THIS DCP A.1.8 RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER PLANS A.1.9 DEVELOPER CONTRIBUTIONS A.1.10 PLANNING AGREEMENTS A.1.11 PRIVATE COVENANTS A.1.12 ANCILLARY DEVELOPMENT A.1.13 CUMULATIVE IMPACTS A.2 TYPES OF DEVELOPMENT A.2.1 INTRODUCTION A.2.2 EXEMPT DEVELOPMENT A.2.3 COMPLYING DEVELOPMENT A.2.4 LOCAL DEVELOPMENT A.2.5 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT A.2.6 DESIGNATED DEVELOPMENT A.2.7 STATE & REGIONAL SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENT A.3 NOTIFICATION & ADVERTISING A.3.1 INTRODUCTION A.3.2 NOTIFIED DEVELOPMENT A.3.3 ADVERTISED DEVELOPMENT A.3.4