Problem of Ezekiel an Inductive Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ezekiel 17:22-24 JESUS: the SHOOT from WHICH the CHURCH GREW Rev

Ezekiel 17:22-24 JESUS: THE SHOOT FROM WHICH THE CHURCH GREW Rev. John E. Warmuth Sometimes when preaching on Old Testament texts, especially gospel promises like this one, a brief review of Old Testament history leading up to the prophecy helps to understand the prophecy. That’s because these gospel promises were given to bring comfort and joy to hearts that were hurting under specific consequences for specific sins. We begin our brief review at the time of King David. Under his rule Israel was a power to be reckoned with. In size it was nearly as big as it would ever be. It was prosperous. Spiritually, it worshipped the true God and enjoyed his fellowship. The people looked forward to King David’s “greater son,” the Christ, the Savior to come. Under King Solomon, David’s son, the nation continued to prosper, worldly speaking. But as often happens, worldly prosperity brought spiritual depravity. False gods found their way into the people’s lives. After Solomon died the nation was split into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. The kings of the northern kingdom all worshiped false gods and led the people to do the same. God sent prophets who warned them of their sin and urged them to turn them back to God. Meanwhile, in the southern kingdom of Judah, some kings were faithful to God and set the example for the nation while others were not. God finally became fed up with the sin of the northern kingdom and sent the Assyrian Empire to destroy it. -

“As Those Who Are Taught” Symposium Series

“AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Symposium Series Christopher R. Matthews, Editor Number 27 “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL Edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Copyright © 2006 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data “As those who are taught” : the interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL / edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull. p. cm. — (Society of biblical literature symposium series ; no. 27) Includes indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-58983-103-2 (paper binding : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-58983-103-9 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Isaiah—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—History. 2. Bible. O.T. Isaiah— Versions. 3. Bible. N.T.—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. McGinnis, Claire Mathews. II. Tull, Patricia K. III. Series: Symposium series (Society of Biblical Literature) ; no. 27. BS1515.52.A82 2006 224'.10609—dc22 2005037099 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

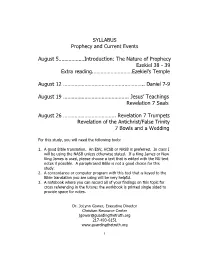

Prophecy and Current Events

SYLLABUS Prophecy and Current Events August 5………………Introduction: The Nature of Prophecy Ezekiel 38 - 39 Extra reading.………………………Ezekiel’s Temple August 12 …………………………………….………….. Daniel 7-9 August 19 ………………………………………. Jesus’ Teachings Revelation 7 Seals August 26 ………………………………. Revelation 7 Trumpets Revelation of the Antichrist/False Trinity 7 Bowls and a Wedding For this study, you will need the following tools: 1. A good Bible translation. An ESV, HCSB or NASB is preferred. In class I will be using the NASB unless otherwise stated. If a King James or New King James is used, please choose a text that is edited with the NU text notes if possible. A paraphrased Bible is not a good choice for this study. 2. A concordance or computer program with this tool that is keyed to the Bible translation you are using will be very helpful. 3. A notebook where you can record all of your findings on this topic for cross referencing in the future; the workbook is printed single sided to provide space for notes. Dr. JoLynn Gower, Executive Director Christian Resource Center [email protected] 217-493-6151 www.guardingthetruth.org 1 INTRODUCTION The Day of the Lord Prophecy is sometimes very difficult to study. Because it is hard, or we don’t even know how to begin, we frequently just don’t begin! However, God has given His Word to us for a reason. We would be wise to heed it. As we look at prophecy, it is helpful to have some insight into its nature. Prophets see events; they do not necessarily see the time between the events. -

Zechariah 9–14 and the Continuation of Zechariah During the Ptolemaic Period

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 13, Article 9 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2013.v13.a9 Zechariah 9–14 and the Continuation of Zechariah during the Ptolemaic Period HERVÉ GONZALEZ Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203L1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs ZECHARIAH 9–14 AND THE CONTINUATION OF ZECHARIAH DURING THE PTOLEMAIC PERIOD HERVÉ GONZALEZ UNIVERSITY OF LAUSANNE INTRODUCTION This article seeks to identify the sociohistorical factors that led to the addition of chs. 9–14 to the book of Zechariah.1 It accepts the classical scholarly hypothesis that Zech 1–8 and Zech 9–14 are of different origins and Zech 9–14 is the latest section of the book.2 Despite a significant consensus on this !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 The article presents the preliminary results of a larger work currently underway at the University of Lausanne regarding war in Zech 9–14. I am grateful to my colleagues Julia Rhyder and Jan Rückl for their helpful comments on previous versions of this article. 2 Scholars usually assume that Zech 1–8 was complete when chs. 9–14 were added to the book of Zechariah, and I will assume the sameT see for instance E. Bosshard and R. G. Kratz, “Maleachi im Zwölfprophetenbuch,” BN 52 (1990), 27–46 (41–45)T O. H. -

Daniel 1. Who Was Daniel? the Name the Name Daniel Occurs Twice In

Daniel 1. Who was Daniel? The name The name Daniel occurs twice in the Book of Ezekiel. Ezek 14:14 says that even Noah, Daniel, and Job could not save a sinful country, but could only save themselves. Ezek 28:3 asks the king of Tyre, “are you wiser than Daniel?” In both cases, Daniel is regarded as a legendary wise and righteous man. The association with Noah and Job suggests that he lived a long time before Ezekiel. The protagonist of the Biblical Book of Daniel, however, is a younger contemporary of Ezekiel. It may be that he derived his name from the legendary hero, but he cannot be the same person. A figure called Dan’el is also known from texts found at Ugarit, in northern Syrian, dating to the second millennium BCE. He is the father of Aqhat, and is portrayed as judging the cause of the widow and the fatherless in the city gate. This story may help explain why the name Daniel is associated with wisdom and righteousness in the Hebrew Bible. The name means “God is my judge,” or “judge of God.” Daniel acquires a new identity, however, in the Book of Daniel. As found in the Hebrew Bible, the book consists of 12 chapters. The first six are stories about Daniel, who is portrayed as a youth deported from Jerusalem to Babylon, who rises to prominence at the Babylonian court. The second half of the book recounts a series of revelations that this Daniel received and were interpreted for him by an angel. -

1-And-2 Kings

FROM DAVID TO EXILE 1 & 2 Kings by Daniel J. Lewis © copyright 2009 by Diakonos, Inc. Troy, Michigan United States of America 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Composition and Authorship ...................................................................................................................... 5 Structure ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Theological Motifs ..................................................................................................................................... 7 The Kingship of Solomon (1 Kings 1-11) .....................................................................................................13 Solomon Succeeds David as King (1:1—2:12) .........................................................................................13 The Purge (2:13-46) ..................................................................................................................................16 Solomon‟s Wisdom (3-4) ..........................................................................................................................17 Building the Temple and the Palace (5-7) .................................................................................................20 The Dedication of the Temple (8) .............................................................................................................26 -

Jeremiah 11:1-13:27

Jeremiah Prophesies Destruction - Jeremiah 11:1-13:27 Topics: Adultery, Anger, Beauty, Bitterness, Commitment, Compassion, Covenant, Darkness, Death, Enemies, Evil, Family, Follow, Forget, Forsake, Fruit, Glory, God, Goodness, Hatred, Heart, Help, Honor, Idolatry, Instructions, Judgment, Justice, Law, Learning, Life, Light, Listening, Lust, Mercy, Mind, Name, Neighbor, Obedience, Pain, People, Praise, Prayer, Pride, Prophecy, Punishment, Questions, Revelation, Revenge, Righteousness, Safety, Shame, Sin, Stubbornness, Swearing, Testing, Trust, Words Open It 1. What is an issue of fairness that has direct impact on your life? * 2. If you knew that someone was trying to kill you, what would you do? Explore It 3. Of what important era in their history did God want Jeremiah to remind Israel? (11:1-5) 4. Why was God punishing His people? (11:9-11) 5. What did God say the people would discover when they sought help from the gods they had been worshiping? (11:12-13) * 6. How did Jeremiah find out about the plot on his life, and where did he turn for help? (11:18-20) 7. What did the Lord promise to do to the people of Anathoth who had threatened Jeremiah? (11:21- 23) 8. What questions did Jeremiah pose to God concerning His justice? (12:1-4) 9. What did God reveal that He intended to do to His unfaithful people? (12:7-13) 10. How would the response of the nations to God’s judgment on Israel affect those nations? (12:14- 17) 11. What physical demonstration did God require of Isaiah as a lesson to the people? (13:1-7) * 12. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

Daily Bible Study “The Tragedy of Hearing Only” Ezekiel 33:30-33 February 27

Daily Bible Study “The Tragedy of Hearing Only” Ezekiel 33:30-33 February 27 – March 5, 2011 THE LORD’S DAY & MONDAY – This week we take a break from our study of the gospel of Mark as we look back into the old Testament to a passage I pray God would use to speak to you through His Word and by His Spirit and challenge you to evaluate your level of love and service to Him. We will be looking at the prophet Ezekiel with Ezekiel 33:30-33 as our main text. Read this passage of Scripture and ask God to help you evaluate your own level of love and service to Him. The prophet Ezekiel, whose name means "strengthened by God", was a man that God called to speak for Him to His exiled people Israel. Ezekiel was himself a captive exiled from his homeland. There were many "false prophets" who were speaking a positive message to the people, assuring them of a speedy return to Judah. Meanwhile, Ezekiel prophesied the truth, which included the foretelling of the destruction of their beloved Jerusalem. Ezekiel also spoke at length to the future restoration of Israel and the final blessings of the Messianic Kingdom. In Ezekiel chapter 1 we are introduced to the prophet and we read of a vision Ezekiel had of God's glory ( Ezekiel 1:1-28 ) and then God speaks to him in chapter 2 ( Ezekiel 1:28 - 2:9) . Read our text for the week in Ezekiel 33:30-33 : “ As for you, son of man, the children of your people are talking about you beside the walls and in the doors of the houses; and they speak to one another, everyone saying to his brother, ‘Please come and hear what the word is that comes from the LORD.’ So they come to you as people do, they sit before you as My people, and they hear your words, but they do not do them; for with their mouth they show much love, but their hearts pursue their own gain. -

Some Forlorn Writings of a Forgotten Ashkenazi Prophet NOTE R

T HE J EWISH Q UARTERLY R EVIEW, Vol. 95, No. 1 (Winter 2005) 183–196 Some Forlorn Writings of a Forgotten Ashkenazi Prophet NOTE R. Nehemiah ben Shlomo ha-Navi’ MOSHE IDEL O WING TO RECENT STUDIES on Haside Ashkenaz, especially by Jo- seph Dan, and the publication of some of the Ashkenazi material from manuscripts, we have a better picture of the literature produced from the early decades of the thirteenth century.1 Of paramount importance to this literature is the distinction Dan drew between different schools emerging out of the Ashkenazi masters. He proposed to distinguish between the main line represented by the writings of the Kalonymite school of R. Yehudah he-Hasid and R. Eleazar of Worms, on the one hand, and the school, which he described as the ‘‘school of the special cherub,’’ on the other.2 In addition, he drew attention to, and eventually printed and ana- lyzed, material that did not belong to either of the two schools and is found in anonymous manuscripts.3 More recently, in an innovative article dealing with the occurrence of the syntagm ‘‘Yeshu‘a Sar ha-panim,’’ Yehudah Liebes has noted dispa- rate anonymous writings found mostly in manuscripts, which belong to an Ashkenazi school, that he called the ‘‘circle of Sefer ha-h. eshek.’’4 He 1. See especially Dan’s The Esoteric Theology of Ashkenazi Hasidism (Hebrew; Jerusalem, 1968); Studies in Ashkenazi-Hasidic Literature (Hebrew; Ramat Gan, 1975); and The ‘‘Unique Cherub’’ Circle (Tu¨ bingen, 1999). 2. Dan, Esoteric Theology, 156–63; Studies, 89–111; The ‘‘Unique Cherub’’ Circle, passim. -

Ezekiel 33. the Turning Point

1 What do you need to know when your world is turned upside down? Ezekiel 33. The Turning Point [33:21] What do you need to know, what should you do, when everything you have taken for granted, the foundational assumptions on which you have built your life, are knocked away in a moment? What do you need to know then? And where can you find a better foundation, a surer foundation on which to build your life? With the uttering of one doom laden sentence “The city has been struck down” Ezekiel 33: 21 In the twelfth year of our exile, in the tenth month, on the fifth day of the month, a fugitive from Jerusalem came to me and said, “The city has Been struck down.” The exiles in Babylon, those to whom Ezekiel has prophesied for the last seven years, have to face the end of everything they have taken for granted and the destruction of their cherished hope. No King of the line of David reigning in Jerusalem – David’s dethroned descendant a prisoner of the pagan Nebuchednezzar no temple. The footstool of the LORD that was meant to make the city inviolable – in ashes, and with it no sacrifice or worship no city of Jerusalem, Zion – the city of God – in ruins, and their families dead or enslaved no land, the land the LORD had promised their fathers, the land to which they longed to return, lost to them forever Where could they now find hope for release and return, for freedom and consolation, for their continuing existence as a people? It is hard to exaggerate the impact of that one sentence.