Rail Electrification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solent to the Midlands Multimodal Freight Strategy – Phase 1

OFFICIAL SOLENT TO THE MIDLANDS MULTIMODAL FREIGHT STRATEGY – PHASE 1 JUNE 2021 OFFICIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 2. STRATEGIC AND POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................... 11 3. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SOLENT TO THE MIDLANDS ROUTE ........................................................................................................ 28 4. THE ROAD ROUTE ............................................................................................................................................................................. 35 5. THE RAIL ROUTE ............................................................................................................................................................................... 40 6. KEY SECTORS .................................................................................................................................................................................... 50 7. FREIGHT BETWEEN THE SOLENT AND THE MIDLANDS .................................................................................................................... -

Flying Into the Future Infrastructure for Business 2012 #4 Flying Into the Future

Infrastructure for Business Flying into the Future Infrastructure for Business 2012 #4 Flying into the Future Flying into the Future têáííÉå=Äó=`çêáå=q~óäçêI=pÉåáçê=bÅçåçãáÅ=^ÇîáëÉê=~í=íÜÉ=fça aÉÅÉãÄÉê=OMNO P Infrastructure for Business 2012 #4 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ________________________________________ 5 1. GRowInG AVIATIon SUSTAInABlY ______________________ 27 2. ThE FoUR CRUnChES ______________________________ 35 3. ThE BUSInESS VIEw oF AIRpoRT CApACITY ______________ 55 4. A lonG-TERM plAn FoR GRowTh ____________________ 69 Q Flying into the Future Executive summary l Aviation provides significant benefits to the economy, and as the high growth markets continue to power ahead, flying will become even more important. “A holistic plan is nearly two thirds of IoD members think that direct flights to the high growth countries will be important to their own business over the next decade. needed to improve l Aviation is bad for the global and local environment, but quieter and cleaner aviation in the UK. ” aircraft and improved operational and ground procedures can allow aviation to grow in a sustainable way. l The UK faces four related crunches – hub capacity now; overall capacity in the South East by 2030; excessive taxation; and an unwelcoming visa and border set-up – reducing the UK’s connectivity and making it more difficult and more expensive to get here. l This report sets out a holistic aviation plan, with 25 recommendations to address six key areas: − Making the best use of existing capacity in the short term; − Making decisions about where new runways should be built as soon as possible, so they can open in the medium term; − Ensuring good surface access and integration with the wider transport network, in particular planning rail services together with airport capacity, not separately; − Dealing with noise and other local environment impacts; − Not raising taxes any further; − Improving the visa regime and operations at the UK border. -

Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Department for Transport

Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Department for Transport 30 August 2017 Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Report OFFICIAL SENSITIVE: COMMERCIAL Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for Department for Transport’s information and use in relation to Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Business Case. Atkins assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. This document has 108 pages including the cover. Document history Job number: 5159267 Document ref: v4.0 Revision Purpose description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Interim draft for client Rev 1.0 - 18/08/2017 comment Revised draft for client Rev 2.0 18/08/2017 comment Revised draft addressing Rev 3.0 - 22/08/2017 client comment Rev 4.0 Final 30/08/2017 Client signoff Client Department for Transport Project Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Document title Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme: KO1 Final Business Case Job no. 5159267 Copy no. Document reference Atkins Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme | Version 4.0 | 30 August 2017 | 5159267 2 Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Report OFFICIAL SENSITIVE: COMMERCIAL Table of contents Chapter Pages Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction 12 1.1. Background 12 1.2. Report Structure 13 2. Scope of the Appraisal 14 2.1. Introduction 14 2.2. Scenario Development 14 3. Timetable Development 18 3.1. Overview 18 4. Demand & Revenue Forecasting 26 4.1. Introduction 26 4.2. Forecasting methodology 26 4.3. Appraisal of Benefits 29 4.4. -

Paris: Trams Key to Multi-Modal Success

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com JANUARY 2016 NO. 937 PARIS: TRAMS KEY TO MULTI-MODAL SUCCESS Innsbruck tramway enjoys upgrades and expansion Bombardier sells rail division stake Brussels: EUR5.2bn investment plan First UK Citylink tram-train arrives ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 Sound Transit Swift Rail 01 Seattle ‘goes large’ A new approach for with light rail plans UK suburban lines 9 771460 832043 For booking and sponsorship opportunities please call +44 (0) 1733 367600 or visit www.mainspring.co.uk 27-28 July 2016 Conference Aston, Birmingham, UK The 11th Annual UK Light Rail Conference and exhibition brings together over 250 decision-makers for two days of open debate covering all aspects of light rail operations and development. Delegates can explore the latest industry innovation within the event’s exhibition area and examine LRT’s role in alleviating congestion in our towns and cities and its potential for driving economic growth. VVoices from the industry… “On behalf of UKTram specifically “We are really pleased to have and the industry as a whole I send “Thank you for a brilliant welcomed the conference to the my sincere thanks for such a great conference. The dinner was really city and to help to grow it over the event. Everything about it oozed enjoyable and I just wanted to thank last two years. It’s been a pleasure quality. I think that such an event you and your team for all your hard to partner with you and the team, shows any doubters that light rail work in making the event a success. -

Network Rail Completes Major Work on £1.5Billion Midland Main Line Upgrade

Network Rail completes major work on £1.5billion Midland Main Line Upgrade May 18, 2021 Network Rail has completed the biggest improvements to the Midland Main Line since it was built, meaning more seats, faster journeys and more reliable services for passengers travelling between the East Midlands and London. In the latest stage of the upgrade, teams have carried out vital work to install new overhead line equipment between Bedford and Corby, as well as improvements to station platforms and major work to upgrade bridges on the route – to make way for electrification between London St Pancras International and Corby. All of this work means there will be 50% more seats for passengers travelling at peak times between Corby and London. The new train timetable was introduced last Sunday (16 May), and East Midlands Railway launched its new all-electric service between Corby and London St Pancras International, providing a sixth train per hour. The upgrade, along with the new timetable, also boosts the number of seats on services across the East Midlands and cuts travel time between London and Derby, Leicester, Sheffield and Nottingham. It’s hoped the improvements will take more cars off the roads, as COVID restrictions ease and passengers return to the railway. Electric trains are quieter and much better for the environment that diesel trains. They produce almost 80% less carbon, benefitting people who live and work near the railway. Gary Walsh, Route Director for Network Rail’s East Midlands route, said: “As passengers return to the railway, it’s great to be welcoming them back with the biggest improvements in a generation on the Midland Main Line. -

Railway Upgrade Plan – London North Eastern and East Midlands (LNE&EM)

Railway Upgrade Plan – London North Eastern and East Midlands (LNE&EM) 2017/18 London North Eastern and East Midlands Glossary CaSL – Cancelled and Significantly Late. This measures how many trains are cancelled or are more than 29 minutes late at their terminating station. MAA – Moving Annual Average. PPM – Public Performance Measure. This is the percentage of trains that arrive at their terminating station within five minutes (for commuter services) or ten minutes (for long distance services) of when they were due. Reduction in railway work complaints measure – We believe that the number of complaints that we receive from the public about our work could be reduced if we improve how we inform people about work due to take place, and ensure all our staff behave considerately towards those living and working close to the railway. Each route is therefore aiming to reduce the number of complaints it receives in the coming year. Right Time Arrival – This measures the percentage of trains arriving at their terminating station early or within 59 seconds of schedule. 16 London North Eastern and East Midlands London North Eastern and East Midlands 17 London North Eastern and East Midlands (LNE&EM) Introduction from the route managing director – Rob McIntosh On LNE&EM, our purpose can be summarised with a simple phrase – we care about our people, we are proud about our work and we are passionate about railways. Each day, we serve around 20 per cent of the UK’s travelling public, with hundreds of commuter and leisure services connecting major cities and conurbations, supporting regional economies up and down the country. -

A Cardiff City Region Metro: Transform, Regenerate, Connect

A Cardiff City Region Metro: transform, regenerate, connect by Mark Barry A Cardiff City Region Metro: transform, regenerate, connect A Cardiff City Region Metro: transform, regenerate, connect Metro Consortium The Metro Consortium is a group of stakeholders who have come together with the common aim of promoting the Metro concept as a regional regeneration project and to actively lobby for a step change in the approach to and investment in, transport across the Cardiff City Region. Membership of the consortium represents a diverse range of interests from the business community, developers, major employers, planning and transport experts who proactively liaise with Welsh Government, Regional Transport Consortia, Local Government and service providers. The core membership of the Consortium includes Capita Symonds, Cardiff Business Partnership, M&G Barry Consulting, Powell Dobson Urbanists, Institute of Welsh Affairs, Jones Lang LaSalle, British Gas, Admiral, Cardiff Business School, Capita Architects, Curzon Real Estates, Paramount Office Interiors, Wardell Armstrong and J.R. Smart. www.metroconsortium.co.uk The Cardiff Business Partnership consists of leading employers in the Capital. Its mission is to represent leading businesses in the Capital of Wales, ensuring that the views of enterprise are at the heart of the development of Cardiff as a competitive business location. The Partnership aims to identify key issues facing the capital’s economy. Through its members who represent the city’s biggest employers, the Partnership has the unique ability to go beyond advocacy to action. The Partnership also serves as a resource of expertise and creative thinking for policy makers, media and others concerned with taking forward the Cardiff and Wales economy. -

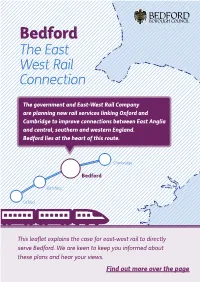

Bedford the East West Rail Connection

Bedford The East West Rail Connection The government and East-West Rail Company are planning new rail services linking Oxford and Cambridge to improve connections between East Anglia and central, southern and western England. Bedford lies at the heart of this route. Cambridge Bedford Bletchley Oxford This leaflet explains the case for east-west rail to directly serve Bedford. We are keen to keep you informed about these plans and hear your views. Find out more over the page Bedford The East-West Rail Connection East-west rail presents a once in a life time opportunity to locate Bedford at the centre of an international and national transport hub. Achieving this will re-establish Bedford on the inter-city network, reversing recent changes and optimizing travel north, south, east and west of Bedford. As a council we recognise the importance of rail and how it can boost the local economy and are calling on the government to support plans for east-west rail through Bedford. The case for east-west rail through central Bedford focuses on three key benefits: 1. Excellent connectivity - locally, nationally and internationally 2. Creating an international business hub 3. Regeneration - boosting jobs and the local economy East-West Rail Company is currently consulting on the future route of the central section of the east-west rail line. Securing east-west rail through Bedford is vital to creating opportunities not only as a key transport hub for both Bedford and the wider national transport network but also in providing key growth and vitality. East-West Rail and International Connectivity East-west rail plans present an excellent opportunity to not only connect the centre of Bedford with Oxford and Cambridge, but also enhance our international connectivity. -

Capacity on North-South Main Lines

Capacity on North-South Main Lines Technical Report Report October 2013 Prepared for: Prepared by: Department for Transport Steer Davies Gleave Click here to enter text. 28-32 Upper Ground London SE1 9PD +44 (0)20 7910 5000 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Technical Report CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... I 1 CREATING THE TIMETABLES THAT DETERMINE CAPACITY PROVISION IS A COMPLEX ISSUE .................................................................................................. 1 2 EUROPEAN COMPARISONS ........................................................................ 5 3 HOW CAPACITY CAN BE MEASURED ............................................................ 7 4 TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES ..................................................................... 9 5 CAPACITY AND THE NORTH-SOUTH ROUTES ................................................ 11 West Coast Main Line .............................................................................. 11 Midland Main Line .................................................................................. 13 East Coast Main Line ............................................................................... 14 Route section categorisation: green/orange/red ............................................ 15 FIGURES Figure 5.1 Assessed post-2019 Capacity Pressures on North-South Main Lines 19 Contents Technical Report Summary 1. This note assesses the capacity of the North-South Rail Lines in the UK from the perspective -

Hsuk London Terminal Strategy

HSUK LONDON TERMINAL STRATEGY In the development of high speed rail systems, the issue of terminal location and onward distribution of passengers assumes almost as much importance as the more obvious question of route. The new lines are designed to carry large volumes of passengers on trains operating at high frequencies, and these factors combine to create major flows arriving at city terminals which must then be efficiently dispersed onto the local public transport networks. This demands full integration of high speed and local systems, with optimised transfer at dedicated and fit-for- purpose terminals. These issues apply at all UK cities where high speed lines are planned, but are most acute in London, where passenger flows are greatest, and congestion in the existing public transport system is most critical. The following diagrams review existing central London connectivity issues, and compare and contrast the London terminal solutions proposed for HS2, and for the alternative High Speed UK proposals. For precise details of the core High Speed UK proposals (as included in the cost estimates), see the ‘200k’ series of plans. LTS1 : LONDON MAIN LINE NETWORK CIRCA 1963 LTS2 : EXISTING CENTRAL LONDON RAIL NETWORK INCLUDING CROSSRAIL SCHEME These diagrams show the rail network of central London, dominated by the classic terminus stations of the Victorian era. These are mostly reliant for onward connectivity upon the Tube network, which tended to form ‘nodes’ around the busier/more important termini. However, the change from main line to Tube is inherently inefficient, with passengers forced to detrain en masse, and with massive congestion occurring especially at rush hours. -

A Powerhouse for the West July 2019

Great Western Powerhouse March 2019 A Powerhouse for the West July 2019 3 Waterhouse Square Elliot House 138 Holborn 151 Deansgate London EC1N 2SW Manchester M3 3WD 020 3868 3085 0161 393 4364 Designed by Bristol City Council, Bristol Design July 19 BD11976 Great Western Powerhouse March 2019 A Powerhouse for the West July 2019 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 THE UK POLICY CONTEXT 8 DEVOLUTION AND THE EMERGING REGIONAL DIMENSION TO UK ECONOMIC AND INDUSTRIAL POLICY 10 INTERNATIONAL MODELS OF CROSS-BORDER COLLABORATION 15 GREAT WESTERN POWERHOUSE GEOGRAPHY 18 ECONOMIC STRENGTHS AND OPPORTUNITIES 30 WHAT THE GREAT WESTERN POWERHOUSE SHOULD BE AIMING TO ACHIEVE 44 c 1 A Powerhouse for the West July 2019 A Powerhouse for the West July 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The economic map of Britain is being reshaped by devolution and the • The Northern Powerhouse and the Midlands The economic geography emergence of regional powerhouses that can drive inclusive growth at scale, Engine have established themselves as formidable regional groupings driving economic The inner core of the region is the cross-border through regional collaboration But, there is a missing piece of the jigsaw in rebalancing and promoting trade and economic relationship between the two metro regions the West of Britain along the M4 from Swindon across the Welsh Border to investment through the internationalisation of of the West of England Region (including Bristol and Swansea, and the intersecting M5 axis, through Bristol, north to Tewkesbury their regions These powerhouses have been -

Newsletter No. 75 MARCH 2018

SARPA Newsletter No.75 Page 1 Shrewsbury Aberystwyth Rail Passengers’ Association Newsletter No. 75 MARCH 2018 ABELLIO NOW DROPS OUT OF BIDDING FOR THE WALES FRANCHISE Abellio has now dropped out of the bidding for the Wales and Borders rail franchise, leaving only MTR and KeolisAmey remaining in the field. Abellio took its decision after much of Carillion's rail assets were bought by rival Amey, which is involved in one of the rival bids, and left it unable to continue. In a statement, Economy Secretary Ken Skates said the Dutch-owned company "has taken the regrettable decision to withdraw its bid having been unable to overcome the impact of Carillion's liquidation". He added: "We have two strong bidders remaining in the process and remain on target to award this exciting contract in May 2018 and to transform rail services in Wales and borders from October 2018." An Abellio spokesman said: "Following the liquidation of Carillion PLC on Monday 15 January, Abellio Rail Cymru has taken the decision to withdraw from the Contract Letting Process for the Wales and Borders Rail Service and South Wales Metro competition.” FRANCHISE TO BE AWARDED IN MAY 2018 AND BE OPERATIONAL IN OCTOBER 2018 The following is a transcript of a recent debate in the Senedd between Leanne Wood AM, the leader of Plaid Cymru and Ken Skates AM., Cabinet Secretary for Economy and Transport. LW: Will the Cabinet Secretary provide an update on the award of the next rail franchise? KS: Yes, of course. Transport for Wales are currently assessing the three bidders for the next Wales and Borders rail services and the South Wales Metro, and the contract will be awarded in May 2018 and it will be operational from October of this year.