Snakebite Treatment Protocol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Grey Turner's and Cullen's Signs Induced by Spontaneous Hemorrhage of the Abdominal Wall After Coughing

CASE REPORT pISSN 2288-6575 • eISSN 2288-6796 https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2017.93.2.115 Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research Grey Turner’s and Cullen’s signs induced by spontaneous hemorrhage of the abdominal wall after coughing Zhe Fan, Yingyi Zhang Department of General Surgery, The Third People’s Hospital of Dalian, Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China Grey Turner’s and Cullen’s signs are rare clinical signs, which most appear in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. The present patient complained of abdominal pain after coughing. However, contrast-enhanced CT revealed a hemorrhage of the abdominal wall. Therefore, spontaneous hemorrhage of the abdominal wall was diagnosed. The patient recovered through immobilization and hemostasis therapy. This case report and literature review aims to remind clinicians of manifestations and treatment of spontaneous hemorrhage. [Ann Surg Treat Res 2017;93(2):115-117] Key Words: Grey Turner’s sign, Cullen’s sign, Spontaneous hemorrhage INTRODUCTION right thigh were noted (Fig. 2). All of the laboratory tests were normal, except that hemoglobin was decreased to 10.5 Grey Turner’s and Cullen’s signs generally suggest a large g/L. Contrastenhanced CT of the abdomen revealed a huge retroperitoneal hematoma, such as hemorrhagic pancreatitis. hematoma in the right lateral abdominal wall (Fig. 3). Therefore, The current case was unusual because of a spontaneous hemo Grey Turner’s and Cullen’s signs induced by spontaneous rrhage of the abdominal wall after coughing leading to Grey hemorrhage of the abdominal wall after cough were diagnosed. Turner’s and Cullen’s signs. -

Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage – a Review of the Eponymous Cutaneous Signs

Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists. 2020; 30(3): 501-506. Review Article Retroperitoneal hemorrhage – A review of the eponymous cutaneous signs Sajad Ahmad Salati Department of Surgery, Unaizah College of Medicine, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia. Abstract Physical diagnosis by eliciting clinical signs still plays an important role in the management of diseases .In case of retroperitoneal bleeding due to any cause, there are five important eponymous cutaneous signs mentioned in literature. These include Cullen’s sign, Turner’s sign, Fox’s sign, Bryant’s sign and Stabler’s sign. These signs are briefly reviewed in this article. Key words Retroperitoneal hemorrhage, Cullen’s sign, Turner’s sign, Fox’s sign, Bryant’s sign, Stabler’s sign. Introduction Web of Science, Semantic Scholar and Reseachgate after search on keywords: In recent years, there have been revolutionary retroperitoneal hemorrhage, skin sign, advances in imaging and diagnostic facilities. eponymous sign and diagnostic sign. The search But in spite of these changes, there are certain was extended across to the cross references. time tested objective physical findings that Only the articles published in English were retain their relevance and importance in eliciting included and no time limits were set. diagnosis or in narrowing the differential diagnosis. The eponymous cutaneous signs of Clinical presentation retroperitoneal hemorrhage are such clinical signs which aid in diagnosis and management of 1. Cullen's sign (Figure 1A) denotes patients besides highlighting the rich history of ecchymosis around the umbilical area as seen dermatology. These eponyms are based on the after retroperitoneal hemorrhage . This sign is physician who first described the clinical accredited to Thomas Stephen Cullen (1868- findings. -

ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Suspected Retroperitoneal Bleed

New 2021 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Suspected Retroperitoneal Bleed Variant 1: Clinically suspected retroperitoneal bleed. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV Usually Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢☢ CTA abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢☢☢ Aortography abdomen and pelvis May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ US abdomen and pelvis Usually Not Appropriate O Radiography abdomen and pelvis Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA abdomen and pelvis without and with Usually Not Appropriate IV contrast O MRA abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI abdomen and pelvis without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast O MRI abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O RBC scan abdomen and pelvis Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Suspected Retroperitoneal Bleed SUSPECTED RETROPERITONEAL BLEED Expert Panel on Vascular Imaging: Nupur Verma, MDa; Michael L. Steigner, MDb; Ayaz Aghayev, MDc; Ezana M. Azene, MD, PhDd; Suzanne T. Chong, MD, MSe; Benoit Desjardins, MD, PhDf; Riham H. El Khouli, MD, PhDg; Nicholas E. Harrison, MDh; Sandeep S. Hedgire, MDi; Sanjeeva P. Kalva, MDj; Yoo Jin Lee, MDk; David M. Mauro, MDl; Hiren J. Mehta, MDm; Mark Meissner, MDn; Anil K. Pillai, MDo; Nimarta Singh, MD, MPHp; Pal S. Suranyi, MD, PhDq; Eric E. Williamson, MDr; Karin E. Dill, MD.s Summary of Literature Review Introduction/Background Retroperitoneal bleeding is a hemorrhage into the retroperitoneal space, the space located posterior to the parietal peritoneum and anterior to the transversalis fascia. -

UNC Aircare Protocol Manuel

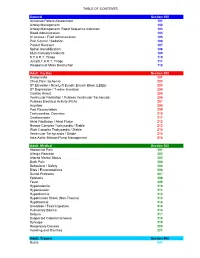

TABLE OF CONTENTS General Section 100 Universal Patient Assessment 101 Airway Management 102 Airway Management: Rapid Sequence Induction 103 Blood Administration 104 IV Access / Fluid Administration 105 Pain Control / Sedation 106 Patient Restraint 107 Spinal Immobilization 108 Multi-Casualty Incidents 109 S.T.A.R.T. Triage 110 JumpS.T.A.R.T. Triage 111 Weapons of Mass Destruction 112 Adult: Cardiac Section 200 Bradycardia 201 Chest Pain: Ischemia 202 ST Elevation / New Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB) 203 ST Depression / T-wave Inversion 204 Cardiac Arrest 205 Ventricular Fibrillation / Pulsless Ventricular Tacharcida 206 Pulsless Electrical Activity (PEA) 207 Asystole 208 Post Resuscitation 209 Tachycardias: Overview 210 Cardioversion 211 Atrial Fibrillation / Atrial Flutter 212 Narrow Complex Tachycardia / Stable 213 Wide Complex Tachycardia / Stable 214 Ventricular Tachycardia / Stable 215 Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump Management 216 Adult: Medical Section 300 Abdominal Pain 301 Allergic Reaction 302 Altered Mental Status 303 Back Pain 304 Behavioral / Safety 305 Bites / Envenomations 306 Dental Problems 307 Epistaxis 308 Fever 309 Hyperkalemia 310 Hypertension 311 Hyperthermia 312 Hypotension Shock (Non-Trauma) 313 Hypothermia 314 Overdose / Toxic Ingestion 315 Pulmonary Edema 316 Seizure 317 Suspected Ceberal Ischemia 318 Syncope 319 Respiratory Distress 320 Vomiting and Diarrhea 321 Adult: Trauma Section 400 Burns 401 TABLE OF CONTENTS Drowning / Near Drowning 402 Electrical Injuries 403 Extremity Trauma 404 Head Trauma / Traumatic -

Chapter 5 – Gastrointestinal System

CHAPTER 5 – GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Nurses in Primary Care. The content of this chapter was revised October 2011. Table of Contents ASSESSMENT OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM ......................................5–1 EXAMINATION OF THE ABDOMEN ........................................................................5–2 COMMON PROBLEMS OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM .........................5–4 Anal Fissure .......................................................................................................5–4 Constipation .......................................................................................................5–5 Dehydration (Hypovolemia) ...............................................................................5–8 Diarrhea ...........................................................................................................5–11 Diverticular Disease .........................................................................................5–15 Diverticulitis ......................................................................................................5–15 Diverticulosis ....................................................................................................5–16 Dyspepsia ........................................................................................................5–17 Gallbladder Disease .........................................................................................5–18 Biliary Colic ......................................................................................................5–21 -

View Sample Pages

THIRD EDITION Randell Alexander, MD, PhD, FAAP Professor of Pediatrics, and Chief Division of Child Protection and Forensic Pediatrics Department of Pediatrics University of Florida Jacksonville, Florida Professor of Pediatrics Morehouse School of Medicine Atlanta, Georgia Angelo P. Giardino, MD, PhD, FAAP Associate Chair – Pediatrics Associate Physician-in-Chief/Vice President, Clinical Affairs St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children Professor in Pediatrics Drexel University College of Medicine Adjunct Professor of Pediatric Nursing LaSalle University School of Nursing Philadelphia, Pennsylvania G.W. Medical Publishing, Inc. St. Louis FOREWORD Child maltreatment is a universal problem. Throughout the world there are parents, neighbors, friends, relatives, school or church workers, and others who fail to value children. Cases of maltreatment involve all socioeconomic classes; no one is exempt. With a scope this all-encompassing, how does one intervene effectively? These children and their families are best served when there is a collective effort by all who are called upon to respond to cases of child maltreatment. Those involved need to understand their respective roles and work together constructively. This means mutual respect and knowledge of how all parts of the system intertwine to provide the best protection for the child and family. The knowledge base in child maltreatment is expanding each day. Whereas in the 1970s there was a paucity of literature devoted to this field, last year there were hundreds of peer-reviewed journal articles written to inform professionals of new findings. These include articles about abuse or neglect as well as conditions that can be mistaken for maltreatment, issues arising in the context of child maltreatment cases, the economic consequences of adverse childhood experiences, the long-term psychological and medical consequences of maltreatment, and the legal aspects of this epidemic. -

Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Hematoma: a Case Report

Clinical Radiology & Imaging Journal Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Hematoma: A Case Report Silva Costa Janson Ney M* Case Report Master's Graduate Program in Medical Sciences at the Federal Fluminense University Volume 2 Issue 3 (UFF), Head of Radiology Service of the Marcilio Dias Navy Hospital (HNMD), Brazil Received Date: August 23, 2018 Published Date: September 04, 2018 Corresponding author: Mônica Silva Costa Janson Ney, Medical doctor, Estrada do Monan 900 casa 62- Niterói- RJ CEP 24320-040, Hospital Naval Marcilio Dias, Brazil, Tel: 55 21 988382607; Email: [email protected] Abstract Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma is a rare condition caused by extravasations of blood into the retroperitoneal space with no history of external trauma or previous vascular procedures. Its clinical presentation can be insidious, evolving for a few days, or sudden, depending on the amount of bleeding. The classic triad of presentation, called Lenk’s triad, characterized by abdominal pain, palpable mass and hypovolemic shock. Diagnosis is made by imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound. Treatment can be surgical or conservative depending on the hemodynamic status of the patient. In the case, the patient presented a sudden low back pain on the left, with a slow decrease in hematocrit, however, no signs of significant hemodynamic changes during hospitalization and the diagnosis was demonstrated by means of abdominal CT that showed the presence massive retroperitoneal hematoma left encompassing the left adrenal and perirenal fascia. There was no report of previous external trauma, but the patient had a regular use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 100 mg daily. The CT scan did not show any other changes that could have caused the bleeding. -

Code of Colorado Regulations

CHAPTER 1 - THE PREHOSPITAL AND TRAUMA REGISTRIES SECTION 1: THE COLORADO TRAUMA REGISTRY 1.1 Definitions Acute trauma injury: An injury or wound to a living person caused by the application of an external force or by violence. Trauma includes any serious life-threatening or limb-threatening situations. Acute trauma involves the initial presentation for care at the facility. Injuries that are not considered to be acute include such conditions as: injuries due to repetitive motion or stress, and scheduled elective surgeries. Admission: inpatient or observation status for greater than 12 hours. Community clinics and community clinics with emergency centers: As defined in the Department’s rules concerning community clinics at 6 CCR 1011-1, Chapter IX. Department: The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment Facility: A health facility licensed by the Department that, under an organized medical staff, offers and provides services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to people in Colorado. Injury type: Can be blunt, penetrating or thermal and is based on the first mechanism of injury. Penetrating injury: Any wound or injury resulting in puncture or penetration of the skin and either entrance into a cavity, or for the extremities, into deeper structures such as tendons, nerves, vascular structures, or deep muscle beds. Penetrating trauma requires more than one layer of suturing for closure. Thermal injury: Any trauma resulting from the application of heat or cold, such as thermal burns, frostbite, scald, chemical burns, electrical burns, lightning and radiation. Blunt injury: Any injury other than penetrating or thermal. Interfacility Transfer: The movement of a trauma patient from one facility to another. -

Delayed Presentation of Shock Due to Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage Following a Fall

Full Text Online @ www.onlinejets.org Shock Scenarios DOI: 10.4103/0974-2700.50753 Delayed presentation of shock due to retroperitoneal hemorrhage following a fall Nader N N Naguib Department of General Surgery, Ain Shams University, Egypt ABSTRACT During trauma the abdomen is one region which cannot be ignored. Due to its Complex anatomy it is very important that all the areas in the abdomen be examined both clinically and radiologicaly to rule out any abdominal bleeding as a cause of Hemorrhagic Shock Following Trauma. Our case justifies the above. Key Words: Blunt abdominal trauma, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, and Shock INTRODUCTION rapid CT examination (without contrast) to rule out a ruptured aneurysm due to the lack of proper history. It was difficult to We present a case with unclear history that turned out to have maintain his vital signs that started to deteriorate again; so he an abdominal cause for his state of shock was rushed to theatre. The CT scan showed a huge multi-locular abdominal cyst with CASE REPORT blood-dense fluid inside. The origin of the cyst was not clear due to its size. There was a tiny calcified structure floating in cyst A 53-year-old well-built man slipped on the floor and landed on cavity. Certainly, the possibility of a leaking aortic aneurysm was his back. He continued to suffer from sharp abdominal pains excluded. There was no other abnormal finding [Figures 1 and 2]. gradually increasing in severity for the following few days. The pain was localized in the epigastrium, left hypochondrium and At the laparotomy, a huge dark blue cyst was filling most of the back. -

Spontaneous Rupture of Renal Angiomyolipoma During Pregnancy

MARIANA MOURAZ LOPES DOS SANTOS1 SARA MARQUES SOARES PROENÇA1 Spontaneous rupture of renal MARIA INÊS NUNES PEREIRA DE AlmEIDA REIS1 RUI MIGUEL ALMEIDA LOPES VIANA1 angiomyolipoma during pregnancy LUÍSA MARIA BERNARDO MARTINS1 JOÃO MANUEL DOS REIS COLAÇO1 Rotura espontânea de um angiomiolipoma durante a gravidez FILOMENA MARIA PINHEIRO NUNES1 Case Report Abstract Keywords Renal angiomyolipoma is a benign tumor, composed of adipocytes, smooth muscle cells and blood vessels. The association Angiomyolipoma/complications with pregnancy is rare and related with an increased risk of complications, including rupture with massive retroperitoneal Angiomyolipoma/diagnosis hemorrhage. The follow-up is controversial because of the lack of known cases, but the priorities are: timely diagnosis Pregnancy complications, neoplastic in urgent cases and a conservative treatment when possible. The mode of delivery is not consensual and should Rupture, spontaneous be individualized to each case. We report a case of a pregnant woman with 18 weeks of gestation admitted in Case reports the emergency room with an acute right low back pain with no other symptoms. The diagnosis of rupture of renal Palavras-chave angiomyolipoma was established by ultrasound and, due to hemodinamically stability, conservative treatment with Angiomiolipoma/complicações imaging and clinical monitoring was chosen. At 35 weeks of gestation, it was performed elective cesarean section Angiomiolipoma/diagnóstico without complications for both mother and fetus. Complicações neoplásicas na gravidez Ruptura espontânea Resumo Relatos de casos O angiomiolipoma é um tumor benigno, constituído por adipócitos, células de músculo liso e vasos sanguíneos. Sua associação com a gravidez é rara e está relacionada com um aumento de complicações, nomeadamente rotura com hemorragia retroperitoneal maciça. -

Guidelines for the Management of Snake-Bites

Guidelines for the management of snake-bites David A Warrell WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data Warrel, David A. Guidelines for the management of snake-bites 1. Snake Bites – education - epidemiology – prevention and control – therapy. 2. Public Health. 3. Venoms – therapy. 4. Russell's Viper. 5. Guidelines. 6. South-East Asia. 7. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia ISBN 978-92-9022-377-4 (NLM classification: WD 410) © World Health Organization 2010 All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication.