Conservation Bulletin 30.Rtf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Site List Fashion, Food & Home

SITE LIST FASHION, FOOD & HOME MARCH 2020 The John Lewis Partnership’s relationships with its suppliers are based on honesty, fairness, courtesy and promptness. In return, the Partnership expects its suppliers to obey the law and to respond the wellbeing of their employees, local communities and the environment. The sites featured in the list below are John Lewis & Partners suppliers’ production sites which represent 100% of John Lewis & Partners’ branded product. Region Number of Sites Africa 23 Americas 14 Arab States 1 Asia Pacific 1195 Europe & Central Asia 526 United Kingdom 548 Total 2307 Active Union or Product No. of Female Male Site Name Address Country Worker Category Workers Worker % Worker % Committee Afa 3 Calzatura Sh.P.K. Velabisht, Beral, Albania Fashion 221 73% 27% Yes Weingut Rabl Weraingraben 10, Langenlois Austria Food 20 25% 75% No Weingut Markus Hurber Cmbh & Cokg Rechersdorf An Der Traisen, Weinriedenweg 13 Austria Food * No Akh Fashions 133-134 Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Dhaka 1340 Bangladesh Fashion 1222 65% 35% Yes Aman Graphics & Designs Ltd Najim Nagar, Dhaka, Savar Bangladesh Fashion 3804 60% 40% Yes Aman Knittings Ltd Kulashur, Hemayetpur, Dhaka, Savar Bangladesh Fashion 1715 46% 54% Yes Bando Eco Apparels Ld. Plot #188/2, Block G-A, Chanpur, Amin Bazar, Savar, Dhaka, Dhaka, Dhaka Bangladesh Fashion 1200 53% 47% Yes Basic Shirts Ltd Plot # 341, Majukhan, Po: Harbaid, Ps Gazipur Sadar, Gazipur Bangladesh Fashion 2410 70% 30% Yes Direct Sports & Leisurewear (Bd) Limited Plot No. S.A. 07, 08, R.S. 11, 12, 13 Karamtola Pubail Gazipur, Dhaka, Bangladesh Fashion 374 65% 35% No Energypac Fashion Ltd. -

RSCM Honorary Awards 1936-2020 Hon

FRSCM (220) ARSCM (196) Hon. Life RSCM (62) RSCM Honorary Awards 1936-2020 Hon. RSCM (111) Cert. Special Service (193) Total 782 Award Year Name Dates Position FRSCM 1936 Sir Arthur Somervell 1863-1937 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Chairman of Council SECM FRSCM 1936 Sir Stanley Robert Marchant 1883-1949 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Principal of the Royal Academy of College FRSCM 1936 Sir Walter Galpin Alcock 1861-1947 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of Salisbury Cathedral FRSCM 1936 Sir Edward Bairstow 1874-1946 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of York Minster FRSCM 1936 Sir Hugh Percy Allen 1869-1946 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Director of the Royal College of Music FRSCM 1936 The Revd Dr.Edmund Horace Fellowes 1870-1951 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Choirmaster of St George's, Windsor and Musicologist FRSCM 1936 Sir Henry Walford Davies 1869-1941 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of the Temple Church FRSCM (i) 1936 Dr Henry George Ley 1887-1962 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Precentor of Eton FRSCM (i) 1936 Sir Ivor Algernon Atkins 1869-1953 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of Worcester Cathedral FRSCM (i) 1936 Sir Ernest Bullock 1890-1979 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of Westminster Abbey FRSCM (iii) 1937 Sir William Harris 1883-1973 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1937. -

KING's LEADERSHIP ACADEMY BOLTON Parent Handbook 2020/21

KING’S LEADERSHIP ACADEMY BOLTON Parent Handbook 2020/21 Credimus KING’S LEADERSHIP ACADEMY BOLTON | PARENT HANDBOOK | 2020-2021 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION [3] Our Curriculum [7] King’s Routines [15] Principal’s Welcome Our Approach Mill Tutor Group Academic Arc Home contact details The Creative Arc The School website Academic Excellence [3] The Leadership Arc Visiting the school School Trips and Other Activities Our Mission taking place Values Strengthen Character Leadership Residential [7] A Personalised Education Paying for School Dinners, Trips, Personalised Support Uniform [17] Leadership is our Specialism The King’s Passport [8] Local Advisory Council (LAC) [4] Uniform Appearance [18] Also known as Governing Body Learning at Home [9] Rational Learning Cycle Assessments Day Uniform Physical Education Uniform Leadership and Staffing [4] Other uniform items Pastoral Care [10] Hair and Makeup Sponsor & Educational Advisor Jewellery and personal items Provision in Years 7 & 8 Safeguarding Mobile Phones Child Protection Religious dress Term Dates [6] Prevention and Bullying Outdoor wear First Aid Complaints School Closures and Notable Dates Attendance Insurance Holiday during term time School Contracts [22] Punctuality Academy Day [6] Medical Visits Contact details IT Acceptable Use Policy - Student Daily Structure Rewards system FAQs [28] Lunch Arrangements Behaviour system 2 KING’S LEADERSHIP ACADEMY BOLTON | PARENT HANDBOOK | 2020-2021 Introduction included as equal partners in the daily life of the academy. Principal’s welcome We believe that the best way to prepare individuals for the future is through ‘Leadership’. Welcome to King’s, a non-selective free independent By adopting this specialism, we will provide school in the state sector that is providing a world class opportunities at all levels for both staff and education for the young people of Great Lever. -

The Queen's Visit

ColumnTHE ISSUE 5 2007 Academic Success We are delighted with the results in this year’s A2 (A-Level) exams. Stoics in this issue: achieved a 100% pass rate at A2, with 70% of Stoics achieving A and B • School News ................... P2-7 Grades. This is a significant increase from 60.7% last year, building on a Old Stoics ........................ P8-9 steady improvement from just 48% in • 2004. One Stoic, Calvin Ho, achieved Old Stoics News ....... P10-14 a remarkable 6 A Grades this summer, • with further 32 achieving at least 3 A Grades: Mia Hulla, Clare Jackson, • School Sport ............. P14-15 Rebecca Nicholl, Emily Ansell, Catriona Beadel, Lara-Clare Bordeaux, Rory End Piece ........................... P16 Brabant, Emma Christie-Miller, Olivia • Collins, Talia Collins, Edward Colville, Fiona Cooper, Chloe Dorrington, Jonathan Elfer, Jack Fillery, Tom Fox, James Gray, Craig Greene, Tabi The Queen’s Visit Jackson-Gee, Tatjana LeBoff, Toby Marshall, Imogen Midwood, Rosie It was a great honour to welcome Her Majesty The Queen Money-Coutts, Romilly Morgan, Julian and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh to Stowe Nesbitt, Alina Nixdorf, Alexander Paul, Bethany Reilly, Tom Stanton, Alice on Thursday 29 November 2007. Thompson, Anita Waterer, India Not since Queen Victoria and Prince new girls and the House team, The Windsor Clive. Albert visited for 3 days in January Queen was given a short tour of the GCSE results improved this year too, 1845 has Stowe had the honour of grounds while The Duke of with the A/A* pass rate rising to 34% hosting the sovereign and her Edinburgh followed a separate of Stoics. -

Site List Fashion, Food & Home

SITE LIST FASHION, FOOD & HOME AUGUST 2019 The John Lewis Partnership’s relationships with its suppliers are based on honesty, fairness, courtesy and promptness. In return, the Partnership expects its suppliers to obey the law and to respond the wellbeing of their employees, local communities and the environment. The sites in the below list represent over 95% of the own-brand products sold at John Lewis & Partners. Region Number of Sites Africa 24 Americas 12 Arab States 1 Asia Pacific 1188 Europe & Central Asia 508 United Kingdom 531 Total 2271 Product No. of Male Female Worker Active Union or Worker Factory Name Address Country Category Workers Worker % % Committee Afa 3 Calzatura Sh.P.K. Velabisht, Beral Albania Fashion 221 27% 73% Yes La Agricola S.A Ruta Provincial N33 Km,, 7,5 Maipu, Mendoza, 5531 Argentina Food 1601 79% 21% Yes Buronga Hill Winery Buronga Hill Winery, Silver City Highway, Buronga, 2739 Australia Food * No Weingut Markus Hurber Cmbh & Cokg Rechersdorf An Der Traisen, Weinriedenweg 13, 3134 Austria Food 30 43% 57% No Akh Fashions 133-134 Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Fashion 1220 35% 65% Yes Aman Graphics & Designs Ltd Najim Nagar, Dhaka Bangladesh Fashion 3804 40% 60% Yes Aman Knittings Ltd Kulashur, Hemayetpur, Dhaka Bangladesh Fashion 1715 54% 46% Yes Basic Shirts Ltd Plot # 341, Majukhan, Po: Harbaid, Ps Gazipur Sadar Bangladesh Fashion 2410 30% 70% Yes Direct Sports & Leisurewear (Bd) Limited Plot No. S.A. 07, 08, R.S. 11, 12, 13 Karamtola Pubail Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Fashion 374 35% 65% No Energypac -

List of Importers Received from Tos

List of importers received from TOs Thailand No. Company Address Phone Email Others 1468 Pattanakarn Rd., Suanluang, Suanluang, 1 Siam Makro Plc. Bangkok. Mackerel 02-0678999 979 / 13-16 SM Building Tower M, Thai Union Phaholyothin Rd., Samsennai, Phayathai, 2 Manufacturing Co., Ltd. Bangkok. 02-2980025 61/469 Moo 6, Taling Chan - Suphanburi Rd., 3 Umea Foods Co., Ltd. Bang Sao Thong, Bangyai, Nonthaburi 02-3616576 97/11, 6th Floor, Rajdamri Road, Lumpini, 4 Big C Supercenter Pathumwan, Bangkok. 02-6550666 39/3 Moo 8, Economic Road 1, Tambon Thasai, 5 UniCredit Amphur Muang, Samut Sakhon 034-424437-42 99/5 Moo 5, Ekachai Rd., Khokham, Muang, 6 Global Glass Co., Ltd. Samut Sakhon, Samut Sakhon 02 4122471-2 Hyde Food Products 16/17 Moo 7 Soi Wat Salut, Bangna-Trad Km. 7 Co., Ltd. 9 Bang Kaew, Bangplee, Samutprakarn 02 7500505 Food Project (Siam) Co., 99/1 Wongwan Industrial Road Khet Chong 8 Ltd. Nonsi Yannawa Bangkok 02-7708888 Thai Union Frozen Products Public 72/1 Moo 7, Economic Road 1, Tambon Thasai, 9 Company Limited Amphur Muang, Samut Sakhon 02-2980029 29 Moo 6, Kantang Rd., Kuanprang, Muang, 10 Trang Seafood Products Trang 075 230717 Thailand imported from Pakistan 1.3 Soi Tha Kham 11, Samae Dam, Bang Khun 1 Tha Khao Fishing Port Thian Bangkok 02-8956390 Sombat Seafood Co., 79 Soi Petchkasem 79 Junction 1 Nongkrue Plu 2 Ltd. Nongkhaem Bangkok Boonsiri Frozen 3 Products Co., Ltd. 159 Moo 9, Nong Phai, Muang, Sisaket, Sisaket 045 634402 Anusorn Mahachai Cold 59/6 Moo 8 Tambon Thasai Muang Samut 4 Storage Sakhon Samut Sakhon 034-414161-4 Friend Food Export Co., 5 Ltd. -

Summer Dining

Richard Haworth Introduces New Bistro Napkins – Press Release April 2017 Richard Haworth – the Manchester based linen supplier – has launched stylish Bistro napkins to complement their already market leading table linen offering. Perfect for casual dining, the napkins are available in three attractive colour stripe options. Established in 1876, the company has long been providing bath, bed and table linens, along with soft furnishings, to the hospitality industry. Indeed its introduction of a cotton-soft polyester table linen range 20 years ago revolutionized the restaurant sector and quickly become the industry standard. Its latest creation bridges the gap between the fine dining aesthetic of pristine tablecloths and the casual setting of paper napkins, offering a high quality napkin which features chic coloured stripes to add a touch of panache to any dining experience. The product, made from 100% jet-spun polyester, has the feel of cotton, yet its increased resilience and toughness make it ideal for the rigours of the hospitality sector. Resistant to snagging and shrinkage, with outstanding absorbency, it is both practical and stylish, perfectly suiting it to its purpose. According to Raj Ruia, managing director: “We’re incredibly excited to unveil our latest collection. The Bistro napkins offer both exceptional quality and a more casual aesthetic, they’re the ideal complement for any table setting.” You can find Richard Haworth linen in venues such as Le Manoir aux Quat'Saisons, Wimbledon tennis club, JP Morgan and Home House in London, all of which the business enjoys long- standing relationships with. Richard Haworth supplies quality linen for the bed, bath, dining room and kitchen to a range of different businesses, including hotels, B&Bs, laundries, restaurants and spas. -

M09124211* Višja Raven ANGLEŠČINA Izpitna Pola 1

Šifra kandidata: Državni izpitni center SPOMLADANSKI IZPITNI ROK *M09124211* Višja raven ANGLEŠČINA Izpitna pola 1 A) Bralno razumevanje B) Poznavanje in raba jezika Sobota, 30. maj 2009 / 80 minut (40 + 40) Dovoljeno gradivo in pripomočki: Kandidat prinese nalivno pero ali kemični svinčnik, svinčnik HB ali B, radirko in šilček. Kandidat dobi list za odgovore. SPLOŠNA MATURA NAVODILA KANDIDATU Pazljivo preberite ta navodila. Ne odpirajte izpitne pole in ne začenjajte reševati nalog, dokler vam nadzorni učitelj tega ne dovoli. Rešitev nalog v izpitni poli ni dovoljeno zapisovati z navadnim svinčnikom. Prilepite kodo oziroma vpišite svojo šifro (v okvirček desno zgoraj na tej strani in na list za odgovore). Izpitna pola je sestavljena iz dveh delov, dela A in dela B. Časa za reševanje je 80 minut. Priporočamo vam, da za reševanje vsakega dela porabite 40 minut. Izpitna pola vsebuje 2 nalogi v delu A in 3 naloge v delu B. Število točk, ki jih lahko dosežete, je 67, od tega 20 v delu A in 47 v delu B. Vsak pravilen odgovor je vreden eno (1) točko. Rešitve, ki jih pišite z nalivnim peresom ali s kemičnim svinčnikom, vpisujte v izpitno polo v za to predvideni prostor. Pri 2. nalogi dela A izpolnite še list za odgovore. Če boste pri tej nalogi pri posameznih postavkah izbrali več odgovorov, bodo ocenjeni z nič (0) točkami. Pišite čitljivo. Če se zmotite, napisano prečrtajte in rešitev zapišite na novo. Nečitljivi zapisi in nejasni popravki bodo ocenjeni z nič (0) točkami. Zaupajte vase in v svoje zmožnosti. Želimo vam veliko uspeha. Ta pola ima 12 strani, od tega 3 prazne. -

Information 83

ISSN 0960-7870 BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY INFORMATION 83 FEBRUARY 2001 OFFICERS OF THE BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY Chairman Terence Paul Smith Flat 6 BA, MA, MLitt 6 Hart Hill Drive LUTON Bedfordshire LU2 0AX Honorary Secretary Michael Hammett ARIBA 9 Bailey Close Tel: 01494-520299 HIGH WYCOMBE E-mail [email protected] Buckinghamshire HP13 6QA Membership Secretary Keith Sanders 24 Woodside Road (Receives all direct subscriptions, £7-00 per annum*) TONBRIDGE Tel; 01732-358383 Kent TN9 2PD E-mail [email protected] Editor of BBS Information David H. Kennett BA, MSc 7 Watery Lane (Receives all articles and items for BBS Information) SHIPSTON-ON-STOUR Tel: 01608-664039 Warwickshire CV36 4BE Honorary Treasurer Mrs W. Ann Los "Peran" (For matters concerning annual accounts, expenses) 30 Plaxton Bridge and Woodmansey Bibliographer BEVERLEY East Yorkshire HU17 0RT Publications Officer Mr John Tibbles Barff House 5 Ash Grove Sigglesthorne HULL East Yorkshire HU11 5QE Enquiries Secretary Dr Ronald J. Firman 13 Elm Avenue (Written enquiries only) Beeston NOTTINGHAM NG9 1BU OFFICERS OF THE BRITISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION : BRICK SECTION* Chairman Terence Paul Smith Address as above Honorary Secretary Michael Hammett Address as above Members of the BAA may join its brick section and, as such, will be eligible for affiliation to the British Brick Society at a reduced annual subscription of £5-00 per annum: for BAA Life Members, the subscription is waivered: they should inform the BAA:BS secretary of their interest so that they can he included in the Membership List. Telephone numbers of members would be helpful for contact proposes, hut will not he included in the Membership List. -

Barbodhan Revised 2005 A4

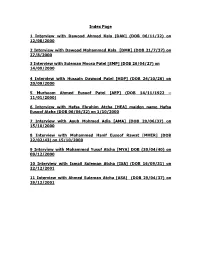

Index Page 1 Interview with Dawood Ahmed Kala [DAK] (DOB 06/11/32) on 12/08/2000 2 Interview with Dawood Mohammed Kala [DMK] (DOB 21/7/37) on 27/8/2000 3 Interview with Suleman Moosa Patel [SMP] (DOB 26/04/27) on 14/09/2000 4 Interview with Hussain Dawood Patel [HDP] (DOB 24/10/26) on 20/09/2000 5 Murhoom Ahmed Eusoof Patel [AEP] (DOB 14/11/1922 – 11/01/2000) 6 Interview with Hafsa Ebrahim Atcha [HEA] maiden name Hafsa Eusoof Atcha (DOB 06/06/32) on 1/10/2000 7 Interview with Ayub Mohmed Adia [AMA] (DOB 20/06/37) on 15/10/2000 8 Interview with Mohammed Hanif Eusoof Rawat [MHER] (DOB 22/02/43) on 15/10/2000 9 Interview with Mohammed Yusuf Atcha [MYA] DOB (30/04/40) on 09/12/2000 10 Interview with Ismail Suleman Atcha [ISA] (DOB 16/09/31) on 22/12/2001 11 Interview with Ahmed Suleman Atcha [ASA] (DOB 29/04/37) on 29/12/2001 12 Interview with Ahmad Ismail Jeewa [AIJ] (DOB 01/01/30) on 30/12/2001 13 Interview with Suleman Dawood Nalla [SDN] (DOB 23/04/39) on 01/01/2002 14 Interview with Hashim Yusuf Atcha [HYA] (DOB 23/08/45) on 29/01/2002 15 Interview with Murhoom Salim Ayoob Atcha [SAA] (DOB 24/05/40) on 03/04/2002 16 Dawood Yacoob Rawat profile sent on 01/02/2002 17 Interview with Zainab Dawood Patail [ZDP] (DOB 15/06/31) on 24/04/2002 18 Interview with Ebrahim Ayoob Nalla [EAN] (DOB 09/11/43) on 02/05/2002 19 Interview with Hawa Bibi Mohammed Atcha [HBMA] Maiden Name Hawa Bibi Ebrahim Atcha (DOB 02/07/37) on 23/10/2002 20 Umar Faruk Dawood Ahmed Kala – (DOB 18/08/56) – Born Rangoon, Burma - Profile sent on 15/10/2002 21 Interview with Haroon Suleman Raja [HSR] (DOB 04/05/30) on 10/07/2003. -

Mills Assessment & Prioritisation Scores

Mills Assessment & Prioritisation Scores Heritage Regeneration Economic Social & Historical Significance Social & Historical Rarity/Importance Listed Status Townscape Catalytic Effect Condition/Risk Viability Physical Adaptability Current Contribution Potential Contribution HERITAGE TOTAL REGENERATION TOTAL ECONOMIC TOTAL TOTAL SCORE MILL Swan Lane Mill No 3, Higher Swan Lane, Bolton ### 2 2 2 ### ### 1 1 1 5 ### ### ### ### Swan Lane Mills 1 & 2, Higher Swan Lane, Bolton ### 2 2 2 ### ### -2 2 1 ### ### ### ### ### Beehive Mill No 1, Crescent Rd ### 2 2 2 ### ### -2 2 1 ### ### ### ### ### Beehive Mill No 2, Crescent Rd ### 2 2 2 ### ### -2 2 1 ### ### ### ### ### Croal Mill, Blackshaw Lane ### 2 2 2 ### ### -2 2 1 ### ### ### ### ### Gilnow Mill, Spa Road ### 2 2 2 ### ### 1 1 0 ### ### ### ### ### Lorne Street Mill No. 3, Lorne St, Farnworth ### 2 2 2 ### ### -1 2 0 ### ### ### ### ### Cobden Mill, Gower St, Farnworth ### 2 2 2 ### ### -1 2 0 ### ### ### ### ### Victoria Mill, Piggott St, Farnworth ### 1 1 2 ### ### -2 2 2 4 ### ### ### ### Lorne Street Mill No. 2, Lorne St, Farnworth ### 2 2 1 ### 1 -1 2 1 3 1 2 3 ### Grecian Mill, Lever St ### 2 2 1 ### ### 2 0 0 ### ### ### 3 ### Kearsley Mill, Crompton Rd, Kearsley ### 2 2 2 ### ### -2 2 1 ### ### ### 2 ### Falcon Mill, Handel St ### 2 2 2 ### ### -2 2 1 ### ### ### ### ### Bolton Textile Mill No. 2, Cawdor St, Farnworth ### 1 1 2 ### ### 2 2 0 5 ### ### ### ### Page 1 of 27 Deane Mill, Deane Road ### 1 1 1 ### ### -1 2 1 ### ### ### ### ### St Helena Mill, St Helena Road ### 2 -

Mills Assessment & Prioritisation Scores

Mills Assessment & Prioritisation Scores Heritage Regeneration Economic Social & Historical Significance Social & Rarity/Importance Listed Status Townscape Effect Catalytic Condition/Risk Viability Adaptability Physical CurrentContribution Potential Contribution HERITAGE TOTAL REGENERATION TOTAL ECONOMIC TOTAL TOTAL SCORE MILL Swan Lane Mill No 3, Higher Swan Lane, Bolton 2 2 2 2 8 2 1 1 1 5 1 2 3 16 Swan Lane Mills 1 & 2, Higher Swan Lane, Bolton 2 2 2 2 8 2 -2 2 1 3 1 2 3 14 Beehive Mill No 1, Crescent Rd 2 2 2 2 8 1 -2 2 1 2 2 2 4 14 Beehive Mill No 2, Crescent Rd 2 2 2 2 8 1 -2 2 1 2 2 2 4 14 Croal Mill, Blackshaw Lane 2 2 2 2 8 1 -2 2 1 2 2 2 4 14 Gilnow Mill, Spa Road 2 2 2 2 8 1 1 1 0 3 1 1 2 13 Lorne Street Mill No. 3, Lorne St, Farnworth 2 2 2 2 8 1 -1 2 0 2 1 2 3 13 Cobden Mill, Gower St, Farnworth 1 2 2 2 7 1 -1 2 0 2 1 2 3 13 Victoria Mill, Piggott St, Farnworth 1 1 1 2 5 2 -2 2 2 4 2 2 4 13 Lorne Street Mill No. 2, Lorne St, Farnworth 2 2 2 1 7 1 -1 2 1 3 1 2 3 13 Grecian Mill, Lever St 2 2 2 1 7 1 2 0 0 3 1 2 3 13 Kearsley Mill, Crompton Rd, Kearsley 2 2 2 2 8 1 -2 2 1 2 1 1 2 12 Page 1 of 28 Falcon Mill, Handel St 2 2 2 2 8 1 -2 2 1 2 1 1 2 12 Bolton Textile Mill No.