The Land and All Its Beauty”: Managing Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore: ANIMALS

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore: ANIMALS A surprising array of animal species can be found within the Lakeshore including amphibians, birds, fish, mammals, mollusks, and reptiles. Use the links provided to help you answer the following questions and learn more about the wildlife of Sleeping Bear. Link: http://www.nps.gov/slbe/naturescience/amphibians.htm 1. How many varieties of salamanders can be found within the Lakeshore? ________________________________________________________________ Link: http://www.nps.gov/slbe/naturescience/birds.htm 2. Name a bird species whose numbers are declining elsewhere, but is readily found in grassland meadows within the Lakeshore. ________________________________________________________________ Link: http://www.nps.gov/slbe/naturescience/pipingplover.htm 3. Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore includes some of the few nesting sites of the piping plover, an endangered shorebird. How many nesting pairs are there in the entire Great Lakes area? ________________________________________________________________ Link: http://www.nps.gov/slbe/naturescience/fish.htm 4. What are alewives, and how did they get into Lake Michigan? ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ 5. What species were introduced into the lake to help reduce alewife numbers? ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Link: http://www.nps.gov/slbe/naturescience/mammals.htm -

Great Lakes Islands: Biodiversity Elements And

GREAT LAKES ISLANDS: BIODIVERSITY ELEMENTS AND THREATS A FINAL REPORT TO THE GREAT LAKES NATIONAL PROGRAM OFFICE OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY AUGUST 6, 2007 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Funding for this project has been provided by the Great Lakes Program Office (GLNPO) of the Environmental Protection Agency (Grant No. Gl-96521901: Framework for the Binational Conservation of Great Lakes Islands). We especially appreciated the support of our project officer, K. Rodriquez, and G. Gulezian, director of the GLNPO. Project team members were F. Cuthbert (University of Minnesota), D. Ewert (The Nature Conservancy), R. Greenwood (U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service), D. Kraus (The Nature Conservancy of Canada), M. Seymour (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service), K. Vigmostad (Principal Investigator, formerly of Northeast-Midwest Institute), and L. Wires (University of Minnesota). Team members for the Ontario portion of the project included W. Bakowsky (NHIC), B. Crins (Ontario Parks), J. Mackenzie (NHIC) and M. McMurtry (NHIC). GIS and technical support for this project has been provided by T. Krahn (Provincial Geomatics Service Centre, OMNR), J. Slatts (The Nature Conservancy), and G. White (The Nature Conservancy of Canada). Many others have provided scientific and policy support for this project. We particularly want to recognize M. DePhillips (The Nature Conservancy), G. Jackson (Parks Canada), B. Manny (Great Lakes Science Center), and C. Vasarhelyi (policy consultant). Cover photograph: A Bay on Gibraltar Island (Lake Erie) ©2005 Karen E. Vigmostad 2 Contents -

2019 Deer Management Unit (Or Area Or Zone) Polygons “Current” (Rev. 2019 Aug. 28)

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES – www.michigan.gov/dnr Wildlife Division FGDC Geospatial Metadata for 2019 Deer Management Unit (or area or zone) polygons “current” (rev. 2019 Aug. 28) By M. Strong, DNR Wildlife Division, Lansing, MI. Description: This file is a shorter summary of longer FGDC geospatial data metadata with important comments, constraints, and qualifiers to accompany geographic information system files (ESRI format shapefile or layer). See the longer more-complete documentation of this data set’s metadata, approximates and follows the FGDC and NBII Metadata Standards at primary required levels, where applicable and appropriate; additional details added if needed. However, these metadata below should include all the mandatory FGDC compliant elements for this data set (a single layer). Some text may be duplicated, but will be improved with next update of these metadata. Data summary/abstract for "deer_management_unit_polygons_current": Description summary: This is the most current white-tailed deer (species Odocoileus virgininus) related management unit, area, or zone polygons; these deer management units (DMUs), special management areas or zones, and other specifically defined polygons are tools DNR staff, particularly DNR Wildlife Division staff, use to manage, represent and depict the extent of deer populations, hunting quotas, open/closed DMUs for applying for drawings or hunting licenses, and other related geospatial activities regarding white-tailed deer. It is your responsibility as a user of these data, to ensure, if you are using these data to determine, plan or do recreational activities, that you personally investigate all regulations or rules related to those activities (acts, place, etc.) before doing those activities or face legal repercussions; if questions, contact DNR offices (http:///www.michigan.gov/dnr ). -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Lighthouses of the Western Great Lakes a Web Site Researched and Compiled by Terry Pepper

A Publication of Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes © 2011, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, P.O. Box 545, Empire, MI 49630 www.friendsofsleepingbear.org [email protected] Learn more about the Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, our mission, projects, and accomplishments on our web site. Support our efforts to keep Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore a wonderful natural and historic place by becoming a member or volunteering for a project that can put your skills to work in the park. This booklet was compiled by Kerry Kelly, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes. Much of the content for this booklet was taken from Seeing the Light – Lighthouses of the Western Great Lakes a web site researched and compiled by Terry Pepper www.terrypepper.com. This web site is a great resource if you want information on other lighthouses. Other sources include research reports and photos from the National Park Service. Information about the Lightships that were stationed in the Manitou Passage was obtained from David K. Petersen, author of Erhardt Peters Volume 4 Loving Leland. http://blackcreekpress.com. Extensive background information about many of the residents of the Manitou Islands including a well- researched piece on the William Burton family, credited as the first permanent resident on South Manitou Island is available from www.ManitouiIlandsArchives.org. Click on the Archives link on the left. 2 Lighthouses draw us to them because of their picturesque architecture and their location on beautiful shores of the oceans and Great Lakes. The lives of the keepers and their families fascinate us as we try to imagine ourselves living an isolated existence on a remote shore and maintaining the light with complete dedication. -

Naming Rationale

Naming Rationale Label-wise, the goal of the map is to illuminate the various landforms of Michigan, of which many residents are quite unaware. It should inform them of existing toponyms, as well as provide new toponyms for noteworthy features which don’t seem to have any. Landform toponyms can be approached from a folk or a technical perspective. A local might refer to the Yellow Hills that lay beside the Green Plain, whereas a physical geographer would recognize the glacial origins of these features and have good reason to call them the Yellow Moraine, next to the Green Glacial Lake Plain. My chosen perspective is folk toponymy. However, for many features in Michigan such names are lacking or poorly-attested, whereas technical names are much more common (experts think about landforms much more than other residents). Therefore I have sometimes borrowed from the list of technical names, modifying them at times to be more folk-like. For some features, the sources I have disagree as to their name or extent. I have done my best to mediate disputes. Other features have names that appear only on a single source, invented by mapmakers who saw landforms languishing in anonymity. I have propagated these names where they seemed sensible to me, and coined some of my own. All toponyms have to start somewhere. The result is a mixture of folk and technical, existing and newly-coined. Another cartographer would, given the same starting materials, produce a different result. I hope though, that my decisions seem justifiable and sound. List of Names and Sources In the pages that follow, I have compiled my notes and sources for every label on the map. -

Lighthouses – Clippings

GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION MILWAUKEE PUBLIC LIBRARY/WISCONSIN MARINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY MARINE SUBJECT FILES LIGHTHOUSE CLIPPINGS Current as of November 7, 2018 LIGHTHOUSE NAME – STATE - LAKE – FILE LOCATION Algoma Pierhead Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan - Algoma Alpena Light – Michigan – Lake Huron - Alpena Apostle Islands Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Apostle Islands Ashland Harbor Breakwater Light – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Ashland Ashtabula Harbor Light – Ohio – Lake Erie - Ashtabula Badgeley Island – Ontario – Georgian Bay, Lake Huron – Badgeley Island Bailey’s Harbor Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bailey’s Harbor Range Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bala Light – Ontario – Lake Muskoka – Muskoka Lakes Bar Point Shoal Light – Michigan – Lake Erie – Detroit River Baraga (Escanaba) (Sand Point) Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Sand Point Barber’s Point Light (Old) – New York – Lake Champlain – Barber’s Point Barcelona Light – New York – Lake Erie – Barcelona Lighthouse Battle Island Lightstation – Ontario – Lake Superior – Battle Island Light Beaver Head Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Beaver Island Beaver Island Harbor Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – St. James (Beaver Island Harbor) Belle Isle Lighthouse – Michigan – Lake St. Clair – Belle Isle Bellevue Park Old Range Light – Michigan/Ontario – St. Mary’s River – Bellevue Park Bete Grise Light – Michigan – Lake Superior – Mendota (Bete Grise) Bete Grise Bay Light – Michigan – Lake Superior -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey -

The Clapboard Newsletter – 2017

Preserve Historic Sleeping Bear The Clapboard Preserving and Interpreting the Historic Structures, Landscapes, and Heritage of Sleeping Bear Dunes FALL 2017 Saving the history—Telling the Story “I personally appreciate the work of Preserve…..I am always humbled by people who donate their time, treasure, and talent to that mission. There are many who love history and who love Sleeping Bear Dunes, but only a fraction of these manifest that love with real effort.” - Tom Ulrich, Deputy Superintendent, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore [Grassroots preservation] is empty pocketbooks, bloody fingers, and private satisfactions. It is long hours, hard work, and no pay. It is a personal dialogue with ghosts. It is a face-to-face confrontation with the past... It is an equation between self and history so powerful that it makes us lie down in front of bulldozers, raise toppled statues, salvage old boats. - Peter Neill, 45th National Preservation Conference [1991] FRONT COVER PHOTO—Kraitz Log Cabin Restoration, summer 2017; TOP PHOTO: The Burfiend farm on Port Oneida road during sunset 2 20 year Celebration Coming Up SUSAN POCKLINGTON, DIRECTOR Next July, Preserve Historic Sleeping Bear (Preserve) will hibit, a reactionary gasp is often celebrate 20 years of serving Sleeping Bear Dunes National heard when visitors see previous Lakeshore as an official partner group. In the pages of this photos of what has now been report, we gratefully highlight the accomplishments of preserved. 2017. Coming up on such a momentous occasion, we’re also On the next page, a sam- pausing to reflect back much further— to 1998—when the pling of before and after photos preservation “movement” at Sleeping Bear Dunes began. -

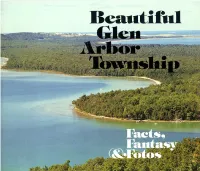

Beautiful Glen Arbor Township Has Been Produced by Scanning the Original Paper Edition Published in 1977 (Second Printing; 1983)

eBook published February 2003 Courtesy of manitoupassage.com eBook Editor’s Notes This transcription of Beautiful Glen Arbor Township has been produced by scanning the original paper edition published in 1977 (second printing; 1983). Printed pages were converted to editable form by optical character recognition (OCR) software, then carefully proofread to correct OCR errors. Obvious spelling, grammar and typographical errors occurring in the original printed edition have also been corrected. The quality of photos and other illustrations in this edition is limited to what could be achieved by scanning the printed versions. Where possible, bitmap graphics have been enhanced using graphics processing software. This eBook version is otherwise a faithful copy of the original printed edition. yyyyy Copyright: No copyright notice appears in this publication. This eBook edition has been created for free distribution. Beautiful Glen Arbor Township Facts, Fantasy & Fotos by Robert Dwight Rader and the GLEN ARBOR HISTORY GROUP Leelanau County, Michigan – 1977 Second Printing – 1983 VILLAGE PRESS (COVER PICTURE: View of Glen Lake taken from Miller’s Hill with Lake Michigan in the distance, the village of Glen Arbor hidden in the trees.) Fisher Mill prologue This book came about as a spin-off of Glen Arbor’s Bicentennial celebration. Gathering infor- mation about historical landmarks for county recognition, locating photos and relics for the mini- museum, tape recording the memories of senior citizens, we re-discovered a vivid past. Many younger members of the community were fasci- nated too. Glen Arbor Township never grew to the greatness of Ann Arbor, or to the fame of other “Glens” and “Harbors” in Michigan. -

Discover North Manitou Island

Discover North Manitou Island A Pocket Guide for Visitors Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore ManitouIslandsArchives.Org acknowledges with Contact & Emergency Information gratitude the cooperation of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore and the National Park Service in the preparation of this visitor’s guide. Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore 9922 Front Street Views and conclusions appearing in this Empire, MI 49630-9797 document are those of the author and should not Ph: 231-326-5134 Fx: 231-326-5382 be interpreted as representing the opinions or Email: [email protected] policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade Internet: www.nps.gov/slbe/ names, commercial products or services does NPS Reservations: 1-888-448-1474 not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. or http:// www.recreation.gov Government. Manitou Island Transit PO Box 591 Leland, MI 49654-0591 Ph: 231-256-9061 Fx: 231-256-7256 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.leelanau.com/manitou/ Cellular Service Wireless service on the Island is spotty and unreliable. Copyright © 2011 Gene L. Warner PO Box 604, Grand Haven, Michigan 49417-0604 USA 911 Emergency Service Not available. Rangers are equipped for direct All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. communications with the mainland. Published in the United States by BoysMindBooks.Com. Island Ranger Station Warner, Gene. Discover North Manitou Island: A Pocket Guide for Visitors Island headquarters are located at the Old Coast ISBN: 978-0-9797896-3-2 Guard Station in the village area by the dock. Website address: www.manitouislandsarchives.org First Edition Published May 2011 i Contents … A Wilderness Adventure Viewed from high atop the giant Sleeping Bear dunes or Contact Information ----------------------------------i Pyramid Point, this mysterious wilderness rises out of the indigo Introduction --------------------------------------------1 depths of the Manitou Passage, daring the adventurous to come. -

2008 Visitor Guide U.S

National Park Service 2008 Visitor Guide U.S. Department of the Interior Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore Your National Park: Explore It! Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore is one of almost 400 sites Spend Saturdays at the Lakeshore Ranger Peg invites you to in the U.S. that are considered so special they are considered national join other Rangers and her for programs every Saturday, January through October. treasures and protected as part of the National Park System. Here Saturday activities begin at the Lakeshore Visitor Center in Empire. In early spring, hunt Ranger Peg highlights some significant features of the Lakeshore. for mushrooms and wildflowers or watch eagles and other birds migrating back to their Whether you have an hour, a day, or a week, you can discover why summer homes. Visit these 72,000 acres of dunes, forests, and beaches were set aside for a beaver lodge in the future generations to enjoy. Grab a park map and let’s get started! summer to witness the work of an ambitious animal, or hike to spooky Take in Pierce Stocking Scenic Drive, a 7.5 mile loop which overlooks Devil’s Hole around some of the Lakeshore’s most unique scenery. You’ll see rare perched dunes, spectacular Halloween. During landscapes carved by glaciers, a fascinating bar lake, the Manitou Passage and much more. January and February, You can stand atop a 450 foot bluff and look straight down at Lake Michigan, or glimpse the explore the winter woods Sleeping Bear Dune a mile north of you. You’ll sense the forces that sculpted the landscape on snowshoes (loaned free long ago and constantly change it today.