Reconsidering Division Cavalry Squadrons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Issue of Saber

1st Cavalry Division Association Non-Profit Organization 302 N. Main St. US. Postage PAID Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 West, TX 76691 Change Service Requested Permit No. 39 SABER Published By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 70 NUMBER 4 Website: www.1CDA.org JULY / AUGUST 2021 It is summer and HORSE DETACHMENT by CPT Siddiq Hasan, Commander THE PRESIDENT’S CORNER vacation time for many of us. Cathy and are in The Horse Cavalry Detachment rode the “charge with sabers high” for this Allen Norris summer’s Change of Command and retirement ceremonies! Thankfully, this (704) 641-6203 the final planning stage [email protected] for our trip to Maine. year’s extended spring showers brought the Horse Detachment tall green pastures We were going to go for the horses to graze when not training. last year; however, the Maine authorities required either a negative test for Covid Things at the Horse Detachment are getting back into a regular swing of things or 14 days quarantine upon arrival. Tests were not readily available last summer as communities around the state begin to open and request the HCD to support and being stuck in a hotel 14 days for a 10-day vacation seemed excessive, so we various events. In June we supported the Buckholts Cotton Festival, the Buffalo cancelled. Thankfully we were able to get our deposits back. Soldier Marker Dedication, and 1CD Army Birthday Cake Cutting to name a few. Not only was our vacation cancelled but so were our Reunion and Veterans Day The Horse Detachment bid a fond farewell and good luck to 1SG Murillo and ceremonies. -

Project Name: Vietnam War Stories

Project Name: Vietnam War Stories Tape/File # WCNAM A26 Operation Cedar Falls Transcription Date: 9/03/09 Transcriber Name: Donna Crane Keywords: Operation Cedar Falls in Jan. 1967, Iron Triangle, hammer and anvil, Ben Suc, villagers preparing for relocation, M-60, M-14 rifles, Viet Cong, Vietcong tunnels, flamethrower, aerial views, soldiers in chow line, 25th Inf. Div., injured soldier, clearing landing zone, confiscated weapons, Gen. William DePuy, Gen. Bernard Rogers, soldiers disembarking from plane [02:00:10.23] Scroll--Operation Cedar Falls, Jan. 1967 explained [02:00:56.13] CV-2 Caribou lands at Tan Son Nhut, soldiers climbing on [02:01:26.02] "Soldiers arrive at Lai Khe, home of 1st Infantry Div.", soldier walking across landing field [02:01:39.20] "UH1D's flying over jungle terrain" [02:01:53.02] "Bomb Craters" [02:02:08.23] Helicopters flying against sunset, aerial view of helicopters in formation [02:02:29.25] Aerial views of "Iron Triangle" [02:03:03.01] Aerial views of "Iron Triangle" [02:03:30.16] "Soldiers landing at Ben Suc" [02:03:50.19] Jeep backs out of Chinook helicopter [02:04:13.04] "Ben Suc villagers leaving" [02:04:32.14] Soldiers running, kneeling down [02:05:01.17] Soldiers walking on path, running [02:05:21.28] "M-60 MG and M-14 rifles" [02:05:37.07] "Villagers assembled for relocation" [02:06:14.13] Military camp [02:06:22.01] "Suspected VC" [02:06:36.04] aerial view of smoking terrain [02:06:59.27] helicopters flying in formation, smoking terrain [02:07:27.13] aerial shot of ground, helicopter flying, group -

A MAGAZINE by and for the 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION the Long Knife

Long Knife The A MAGAZINE BY AND FOR THE 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION LONG KNIFE 4 The Long Knife PUBLICATION STAFF: PURPOSE: The intent of The Long Knife publication is Col. Stephen Twitty to provide information to the Commander, 4th BCT Soldiers and family members of the brigade in regards to our Command Sgt. Maj. Stephan deployment in Iraq. Frennier, CSM,4th BCT, 1st Cav. Div. DISCLAIMER: The Long Maj. Roderick Cunningham Knife is an authorized pub- 4th BCT Public Affairs Officer lication for members of the Editor-in-Chief Department of Defense. The Long Knife Contents of The Long Knife are not necessarily the official Sgt. 1st Class Brian Sipp views of, or endorsed by, the 4th BCT Public Affairs NCOIC U.S. Government or Depart- Senior Editor, The Long Knife ment of the Army. Any edito- rial content of this publication Command Sgt. Maj. David Null, top enlisted mem- Sgt. Paula Taylor is the responsibility of the 4th ber, 27th Brigade Support Battalion, hangs his bat- 4th BCT Public Affairs- Brigade Combat Team Public talion flag on their flagpole after his unit’s Transfer Affairs Office. of Authority ceremony Dec. 5. Print Journalist Editor, The Long Knife This magazine is printed FOR FULL STORY, SEE PAGES 10-11 by a private firm, which is not affiliated with the 4th BCT. All 4 A Soldier remembered BN PA REPRESENTATIVE: copy will be edited. The Long 2nd Lt. Richard Hutton Knife is produced monthly 5 Vice Gov. offers optimism 1-9 Cavalry Regiment by the 4th BCT Public Affairs Office. -

A MAGAZINE by and for the 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION Inside This Issue

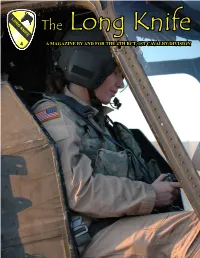

Long Knife The A MAGAZINE BY AND FOR THE 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION LONG KNIFE 4 Inside this issue 5 1-17 Cav provides eyes over the battlefield 8 MEDEVAC crew renders aid 10 3-4 Cav teaches ISF first aid 12 403rd helps rebuild Iraq 14-15 2-7 conducts Operation Harpy 16 2IA takes battle space 19 EOD trains IA counterparts 20 Notes from home An Iraqi Army Soldier, working with Coalition 22-27 Around the battalions Forces, removes unexploded ordinance and prepares it for demolition. FOR FULL STORY, SEE PAGE 19 COVER PHOTO: Kiowa pilot, 1st Lt. Lori Bigger, B BACK COVER PHOTO: In loving memory of our Troop, 1st Squadron, 17th Cavalry Regiment, conducts fallen comrades who lost their lives Jan. 15: Sgt. Ian radio checks as part of her preflight inspection of her Anderson, Staff Sgt. John Cooper, 2nd Lt. Mark OH-58 helicopter before a mission Jan. 10. (U.S. Army Daily and Cpl. Matthew Grimm, and on Jan. 19: Sgt. Photo by Sgt. Paula Taylor) 1st Class Russell Borea and on Jan 22: Spc. Nicholas Brown. (U.S. Army Photo by Sgt. 1st Class Brian Sipp) PUBLICATION STAFF: Commander, 4th BCT.......................................................................................................................................................................................................... Col. Stephen Twitty CSM,4th BCT, 1st Cav. Div. ..................................................................................................................................................................Command Sgt. Maj. Stephan Frennier 4th BCT Public Affairs -

W Vietnam Service Report

Honoring Our Vietnam War and Vietnam Era Veterans February 28, 1961 - May 7, 1975 Town of West Seneca, New York Name: WAILAND Hometown: CHEEKTOWAGA FRANK J. Address: Vietnam Era Vietnam War Veteran Year Entered: 1968 Service Branch:ARMY Rank: SP-5 Year Discharged: 1971 Unit / Squadron: 1ST INFANTRY DIVISION 1ST ENGINEER BATTALION Medals / Citations: NATIONAL DEFENSE SERVICE RIBBON VIETNAM SERVICE MEDAL VIETNAM CAMPAIGN MEDAL WITH '60 DEVICE ARMY COMMENDATION MEDAL 2 OVERSEAS SERVICE BARS SHARPSHOOTER BADGE: M-16 RIFLE EXPERT BADGE: M-14 RIFLE Served in War Zone Theater of Operations / Assignment: VIETNAM Service Notes: Base Assignments: Fort Belvoir, Virginia - The base was founded during World War I as Camp A. A. Humphreys, named for Union Civil War general Andrew A. Humphreys, who was also Chief of Engineers / The post was renamed Fort Belvoir in the 1930s in recognition of the Belvoir plantation that once occupied the site, but the adjacent United States Army Corps of Engineers Humphreys Engineer Center retains part of the original name / Fort Belvoir was initially the home of the Army Engineer School prior to its relocation in the 1980s to Fort Leonard Wood, in Missouri / Fort Belvoir serves as the headquarters for the Defense Logistics Agency, the Defense Acquisition University, the Defense Contract Audit Agency, the Defense Technical Information Center, the United States Army Intelligence and Security Command, the United States Army Military Intelligence Readiness Command, the Missile Defense Agency, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, all agencies of the United States Department of Defense Lai Khe, Vietnam - Also known as Lai Khê Base, Lai Khe was a former Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and U.S. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

World War II Operations Reports 1940-1948 1St Cavalry Division

Records of the Adjutant General's Office (RG407) World War II Operations Reports 1940-1948 陸軍省高級副官部文書 第二次世界大戦作戦記録 1st Cavalry Division 第 1 騎兵師団 Box 16389– Box 16537 国立国会図書館憲政資料室 2008年3月PDFファイル作成 Records of the Adjutant General's Office; World War II Operations Reports 1940-1948 (陸軍省高級副官部文書/第二次世界大戦作戦記録) Series: 1st Cavalry Division Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(1) Folder title: Army Ground Forces Fact Sheet - 1st Cavalry Division Date: 1947/03-1947/03 Item description: Note: Microfiche no. : WOR 40199 Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(2) Folder title: 901-0: The Story of Fort Bliss (Feb 1940) Date: 1940/02-1940/02 Item description: Note: Microfiche no. : WOR 40199 Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(3) Folder title: 901-0: 1st Cavalry Division in World War II - Road to Tokyo (1921 - 1946) Date: 1845/03-1946/03 Item description: Includes Standard Photo(s). Note: Microfiche no. : WOR 40199-40201 Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(4) Folder title: 901-0: 1st Cavalry Division - Historical background - Luzon Campaign (1945) Date: 1947/01-1947/01 Item description: Note: Microfiche no. : WOR 40201 Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(5) Folder title: 901-0: 1st Cavalry Division - Souvenir Battle Diary, Tokyo, Japan (Jul 1943 - 8 Sep 1945) Date: 1946/01-1946/01 Item description: Includes Standard Photo(s). Note: Microfiche no. : WOR 40201-40202 Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(6) Folder title: 901-0: 1st Cavalry Division - Occupation Diary in Japan (1945 - 1950) Date: 1950/05-1950/05 Item description: Includes Standard Photo(s). Note: Microfiche no. : WOR 40202-40203 Box no. (Folder no.): 16389(7) Folder title: 901-0.1: 1st Cavalry Division - History (31 Aug 1921 - 1941) 1 Records of the Adjutant General's Office; World War II Operations Reports 1940-1948 (陸軍省高級副官部文書/第二次世界大戦作戦記録) Series: 1st Cavalry Division Date: ?/?-?/? Item description: Note: Microfiche no. -

Air Base Defense Rethinking Army and Air Force Roles and Functions for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N ALAN J. VICK, SEAN M. ZEIGLER, JULIA BRACKUP, JOHN SPEED MEYERS Air Base Defense Rethinking Army and Air Force Roles and Functions For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR4368 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0500-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The growing cruise and ballistic missile threat to U.S. Air Force bases in Europe has led Headquarters U.S. -

Operation Junction City, Vietnam, 1967

z> /- (' ~/197 OPERATION JUNCTION CITY VIETNAM 1967 BATTLE BOOK PREPARED FOR ADVANCED BATTLE ANALYSIS S U. S. ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE 1983 DTO SEc-rEl MAR 2 9 1984 Pj40 , A .......... ...... ...... SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OP THIiS PAGE (Whm, bets BIntrdM_____________ IN~STRUCTIONS REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1 BEI -. COMhP~LETING FORK I.FEPORT .UM lEf IL GOVT ACCESSION NO- 3. NaCIP" CATALOG HUMWER 4. TITLE (und SubtitS.) S. TYPE of RZEPORT & PVMoD COVERED G. PaRPORMING ORO. REPORT NUNGER 7. AU Memo) 0. CONNTRACT Oft GRANT NUMUErP-( Fetraeus, CIT I.A. S-tuart, i'AJ B.L. Critter~den, ?'AJ D.P. Ceorge 3. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. PROGRAM ZLENMENT. PROJECT, TASK Conhat Studies Institute, 1.SACGSC AREA & WORKC UNIT NUMBERS ATZ!- -S-I 1ct. Leavenworth, YS 66027 It. C*NY ROL.IN@ OFFPICE NAMER AND ADDRESS IL REPORT DATE Con'Sat Studies Institute, 1ISACCSC 3 J6une 195' ATZI,-S 7I 12. pIIMeve OF PAGES F~t. Leavenwerth, FS 66027 v 9ý 4& mMOiTORINGAGELNCY NAME & ADDRELSSWi dSUffeaI fr CU.nIV1d OffiI*) IS. SECURITY CLASS. (*I WelS repet) Unclass-!fled I" DECk S PicA^TioNlrowNORAOIMG 6s. DISTRIBUTION STATERMENT (of Akio R*PaW) 17. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (*I I%. ababasi ml angod In 81&4k 20. It diffe.,ot be. RpmW IL. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES !art of the ?attle Analysis series rrepared by students of the !'S Arr'y Cor~rard and Ceneral Staff Colle~e under the murerviaion of Com~ba~t Studies Ir~stitute. IS. KEY WORDMS (CMthmsg.o roel sde it mmee..w med IdsnUlj' by 650ek inmbW) Fistorry, C^a.ze Studies, 'ilitary Cperatione, Tactical Analysis, Battles, Yllitaznv Tactics, Tactical l-arfare, Airborne, Airr'obile Cperations, Arnor, Artillery, Cavalry, Infantry, Limited 7varh're, Tactical Air Support, Tarn's (Con'bat Vehicles). -

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Association for Diplomatic Studies and Train

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training oreign Affairs Oral History Pro$ect RUFUS PHILLIPS Interviewed by: Ted Gittinger Initial interview date: March 4, 1982 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background University of Virginia Law School Served briefly with CIA US Army, Korean ,ar, Vietnam ,ar Vietnam ,ar 1.5011.52 Saigon 3ilitary 3ission North Vietnamese Catholics Colonel Lansdale Use of rench language Joe Ban4on Soc Trang Province Hanh Diem 3agsaysay Ambassador 5eneral Lawton Collins 6retired7 Liaison Officer Ca 3au operation Operation Brotherhood ilipinos Reoccupation of 8one 5 rench Operation Atlante 5eneral 3ike O9Daniel Colonel Kim Training Relations Instruction 3ission 6TRI37 Viet 3inh evacuation rench1Diem relations Resentment of Viet 3inh 3AA5 Binh :uyen Central Intelligence Agency 6CIA7 1 Vietnamese psywar school Setting up 515 staff Kieu Cong Cung Civil Action Pro$ect AID 3ission Re1organi4ation of Vietnamese army Viet 3inh preparations for resurgence in South Pre1Ho Chi 3inh Trail Civil 5uard Colonel Lansdale Tran Trung Dung 3ontagnards Destabili4ing Viet 3inh regime Almanac incidents Bui An Tuan Vietnam ;uoc Dan Dang 6VN;DD7 Truong Chinh Political Program for Vietnam 5eneral O1Daniel Ambassador Collins/CIA relations Land Reform ,olf Lade$isky Saigon racketeering operations rench anti1US operations Saigon bombing US facilities Howie Simpson Bay Vien rench 5eneral Ely Trinh 3inh Thé Vietnamese/ rench relations Romaine De osse rench deal with Ho Chi -

Indian Army in the Ypres Salient World War I (1914-1918)

Indian Army in the Ypres Salient World War – I (1914-1918) According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 138,000 soldiers from India were sent to Europe during the First World War. Most of these soldiers were deployed in the Ypres Salient and at nearby Neuve Chapelle in France during the period 1914-15. A very large number lost their lives in the campaign to halt the German advance. 2. The Indian Army’s involvement on the Western front started on 6 August 1914. That day, the War Council in London requested two infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade from the Viceroy's government to be sent to Egypt. On 27th August, these troops were ordered to Europe. 3. The supreme sacrifice of Indian soldiers in Europe is recorded in the major World War One memorial in continental Europe, Menin Gate, in Ypres, Belgium, and at the memorial for Indian soldiers in near-by Neuve Chappelle in France. In 2002, at the request of the Government of India, an Indian Memorial was erected on the lawn south of the Menin Gate. 4. After the war, India participated in the peace conference held in Versailles and was represented by Edwin Montague, the Secretary of State for India, Lord Satyendra Nath Sinha and His Highness Maharaja Ganga Singh of Bikaner. The Peace Treaty of Versailles was signed by Mr. Montague and His Highness Maharaja Ganga Singh and India became an original member of the League of Nations. In 1945, when the conference to establish the United Nations Organisation was held in San Francisco, India participated and signed the Charter becoming a founding member of the United Nations. -

War on Film: Military History Education Video Tapes, Motion Pictures, and Related Audiovisual Aids

War on Film: Military History Education Video Tapes, Motion Pictures, and Related Audiovisual Aids Compiled by Major Frederick A. Eiserman U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027-6900 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Eiserman, Frederick A., 1949- War on film. (Historical bibliography ; no. 6) Includes index. 1. United States-History, Military-Study and teaching-Audio-visual aids-Catalogs. 2. Military history, Modern-Study and teaching-Audio- visual aids-Catalogs. I. Title. II. Series. E18I.E57 1987 904’.7 86-33376 CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................. vii Chapter One. Introduction ............................... 1 1. Purpose and Scope .................................. 1 2. Warnings and Restrictions .......................... 1 3. Organization of This Bibliography .................. 1 4. Tips for the Instructor ............................... 2 5. How to Order ........................................ 3 6. Army Film Codes ................................... 3 7. Distributor Codes .................................... 3 8. Submission of Comments ............................ 5 Chapter Two. General Military History ................. 7 1. General .............................................. 7 2. Series ................................................ 16 a. The Air Force Story ............................. 16 b. Air Power ....................................... 20 c. Army in Action ................................. 21 d. Between the Wars ..............................