Reconstructing Justice: Race, Generational Divides, and the Fight Over “Defund the Police”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me

“OVERPOLICED AND UNDERPROTECTED”:1 RACIALIZED GENDERED VIOLENCE(S) IN TA-NEHISI COATES’S BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME “SOBREVIGILADAS Y DESPROTEGIDAS”: VIOLENCIA(S) DE GÉNERO RACIALIZADA(S) EN BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME, DE TA-NEHISI COATES EVA PUYUELO UREÑA Universidad de Barcelona [email protected] 13 Abstract Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me (2015) evidences the lack of visibility of black women in discourses on racial profiling. Far from tracing a complete representation of the dimensions of racism, Coates presents a masculinized portrayal of its victims, relegating black women to liminal positions even though they are one of the most overpoliced groups in US society, and disregarding the fact that they are also subject to other forms of harassment, such as sexual fondling and other forms of abusive frisking. In the face of this situation, many women have struggled, both from an academic and a political-activist angle, to raise the visibility of the role of black women in contemporary discourses on racism. Keywords: police brutality, racism, gender, silencing, black women. Resumen Con la publicación de la obra de Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me (2015) se puso de manifiesto un problema que hacía tiempo acechaba a los discursos sobre racismo institucional: ¿dónde estaban las mujeres de color? Lejos de trazar un esbozo fiel de las dimensiones de la discriminación racial, la obra de Coates aboga por una representación masculinizada de las víctimas, relegando a las miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 62 (2020): pp. 13-28 ISSN: 1137-6368 Eva Puyuelo Ureña mujeres a posiciones marginales y obviando formas de acoso que ellas, a diferencia de los hombres, son más propensas a experimentar. -

Policing, Protest, and Politics Syllabus

Policing, Protest, and Politics: Queers, Feminists, and #BlackLivesMatter WOMENSST 295P / AFROAM 295P Fall 2015 T/Th 4:00 – 5:15pm 212 Bartlett Hall Instructor: Dr. Eli Vitulli Office: 7D Bartlett Email: [email protected] Office hours: Th 1:30-3:30pm (& by appointment only) COURSE OVERVIEW Over the past year few years, a powerful social movement has emerged to affirm to the country and world that Black Lives Matter. Sparked by the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in Stanford, Florida, and Zimmerman’s acquittal as well as the police killings of other black men and women, including Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, and Freddie Gray, this movement challenges police violence and other policing that makes black communities unsafe as well as social constructions of black people as inherently dangerous and criminal. Police violence against black people and the interrelated criminalization of black communities have a long history, older than the US itself. There is a similarly long and important history of activism and social movements against police violence and criminalization. Today, black people are disproportionately subject to police surveillance and violence, arrest, and incarceration. So, too, are other people of color (both men and women) and queer, trans, and gender nonconforming people of all races but especially those of color. This course will examine the history of policing and criminalization of black, queer, and trans people and communities and related anti-racist, feminist, and queer/trans activism. In doing so, we will interrogate how policing and understandings of criminality—or the view that certain people or groups are inherently dangerous or criminal—in the US have long been deeply shaped by race, gender, and sexuality. -

Release Tacoma Creates Funding

From: Lyz Kurnitz‐Thurlow <[email protected]> Sent: Wednesday, May 27, 2020 2:08 PM To: City Clerk's Office Subject: Protect Tacoma's Cultural Sector ‐ Release Tacoma Creates Funding Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Flagged Tacoma City , I respectfully request that the Tacoma City Council take action and unanimously approve the voter-approved work of Tacoma Creates and the independent Citizen panel’s recommendations on this first major round of Tacoma Creates funding, and to do so on the expedited timeline and process suggested by Tacoma City Staff. Please put these dollars to work to help stabilize the cultural sector. This dedicated funding will flow to more than 50 organizations and ensure that our cultural community remains strong and serves the entire community at a new level of impact and commitment. Lyz Kurnitz-Thurlow [email protected] 5559 Beverly Ave NE Tacoma, Washington 98422 From: Resistencia Northwest <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, June 9, 2020 3:57 PM To: City Clerk's Office Subject: public comment ‐ 9 June 2020 Attachments: Public Comment ‐ 9 June 2020 ‐ Resistencia.pdf Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Flagged Our comment for tonight's City Council meeting is attached below. There are questions - when can we expect answers? Thanks, La Resistencia PO Box 31202 Seattle, WA 98103 Web | Twitter | Instagram | Facebook Public Comment, City of Tacoma 9 June 2020 From: La Resistencia The City of Tacoma has only recently begun to recognize the violence, racism, and insupportability of a private prison for immigration in a polluted port industrial zone. We continue to call for the City of Tacoma to show support and solidarity for those in detention at NWDC, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. -

THE FREE-MARKET WELFARE STATE: Preserving Dynamism in a Volatile World

Policy Essay THE FREE-MARKET WELFARE STATE: Preserving Dynamism in a Volatile World Samuel Hammond1 Poverty and Welfare Policy Analyst Niskanen Center May 2018 INTRODUCTION welfare state” directly depresses the vote for reac- tionary political parties.3 Conversely, I argue that he perennial gale of creative destruc- the contemporary rise of anti-market populism in tion…” wrote the economist Joseph America should be taken as an indictment of our in- 4 Schumpeter, “…is the essential fact of adequate social-insurance system, and a refutation “T of the prevailing “small government” view that reg- capitalism.” For new industries to rise and flourish, old industries must fail. Yet creative destruction is ulation and social spending are equally corrosive to a process that is rarely—if ever—politically neu- economic freedom. The universal welfare state, far tral; even one-off economic shocks can have lasting from being at odds with innovation and economic political-economic consequences. From his vantage freedom, may end up being their ultimate guaran- point in 1942, Schumpeter believed that capitalism tor. would become the ultimate victim of its own suc- The fallout from China’s entry to the World Trade cess, inspiring reactionary and populist movements Organization (WTO) in 2001 is a clear case in against its destructive side that would inadvertently point. Cheaper imports benefited millions of Amer- strangle any potential for future creativity.2 icans through lower consumer prices. At the same This paper argues that the countries that have time, Chinese import competition destroyed nearly eluded Schumpeter’s dreary prediction have done two million jobs in manufacturing and associated 5 so by combining free-markets with robust systems services—a classic case of creative destruction. -

2018 Community Board Profiles

2018 Community Board Profiles Members and Demographics Report Brooklyn Borough President Eric L. Adams 1 Table of Contents Filling vacancies and ensuring inclusion 3 Community Board 1 5 Community Board 2 10 Community Board 3 14 Community Board 4 19 Community Board 5 23 Community Board 6 28 Community Board 7 32 Community Board 8 37 Community Board 9 41 Community Board 10 45 Community Board 11 49 Community Board 12 53 Community Board 13 57 Community Board 14 62 Community Board 15 66 Community Board 16 71 Community Board 17 75 Community Board 18 79 2 Filling vacancies and ensuring inclusion When the Office of the Brooklyn Borough President (the Office) has a vacancy on any one of Brooklyn’s 18 community boards, it is brought to the attention of the Brooklyn borough president. The appointed liaison of those boards reviews the applications of those who were not appointed during the general process and selects an individual based upon how often they attend the meetings, their community involvement, and their career background. Other selection criteria may include factors that would increase the diversity of representation on the board, including age, gender identity, geographic location, and race/ethnicity. If the council member has a vacancy on the board, it is brought to the attention of the Brooklyn borough president’s board liaison and/or community board office, and the Office reaches out to the council member's office to inform them that there is a vacancy. The council member will provide their recommendations to the Office to determine who would be the best candidate. -

820 First St NE #675 Washington, DC 20002 Climate Policy and Litigation

820 First St NE #675 Washington, DC 20002 Climate Policy and Litigation Program Report FY 2018-2019 December 2019 The Niskanen Center’s Climate Policy and Litigation Program Report 2018 through 2019 Over the reporting period, Niskanen’s climate team has achieved significant progress toward each of our targeted intermediate outcomes and laid the groundwork to reach our ultimate objectives. We describe those accomplishments and what we have learned in the following report, and discuss where our strategic outlook has been reinforced and where it has been altered. Our focus remains on turning the Niskanen Center’s climate program into one of the most influential, informative, and innovative in Washington, D.C. When the Niskanen Center opened its doors five years ago, and even when the reporting period for our program initiated two years ago, leading Republicans embraced climate skepticism and were occupied with deconstructing the Obama Administration’s climate agenda. There had not been a bipartisan bill supporting carbon pricing since the failure of Waxman-Markey in 2009. Now, we see Republicans acknowledging the reality of human-caused climate change and seeking solutions of varying ambition. At the highest levels, several Republican members of Congress have introduced carbon tax legislation with prices over $30 per ton of CO2 emissions, which—were they law—would be the most ambitious national climate policy globally. The developments portend further progress in the coming years, as bipartisan groups of legislators can embrace both sectoral and comprehensive reforms. The Niskanen Center has been at the heart of these developments. Over the reporting period, Niskanen Center staff have provided policy input and advice for carbon pricing bills that have achieved bipartisan support, been asked for information on climate change and the available responses from formal and informal groups of legislators, and maintained a high volume of public appearances and commentary promoting market-based reforms to achieve a low-carbon economy. -

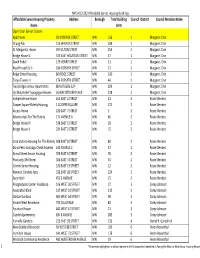

Master 202 Property Profile with Council Member District Final For

NYC HUD 202 Affordable Senior Housing Buildings Affordable Senior Housing Property Address Borough Total Building Council District Council Member Name Name Units Open Door Senior Citizens Apartment 50 NORFOLK STREET MN 156 1 Margaret Chin Chung Pak 125 WALKER STREET MN 104 1 Margaret Chin St. Margarets House 49 FULTON STREET MN 254 1 Margaret Chin Bridge House VI 323 EAST HOUSTON STREET MN 17 1 Margaret Chin David Podell 179 HENRY STREET MN 51 1 Margaret Chin Nysd Forsyth St Ii 184 FORSYTH STREET MN 21 1 Margaret Chin Ridge Street Housing 80 RIDGE STREET MN 100 1 Margaret Chin Tanya Towers II 174 FORSYTH STREET MN 40 1 Margaret Chin Two Bridges Senior Apartments 80 RUTGERS SLIP MN 109 1 Margaret Chin Ujc Bialystoker Synagogue Houses 16 BIALYSTOKER PLACE MN 128 1 Margaret Chin Independence House 165 EAST 2 STREET MN 21 2 Rosie Mendez Cooper Square Elderly Housing 1 COOPER SQUARE MN 151 2 Rosie Mendez Access House 220 EAST 7 STREET MN 5 2 Rosie Mendez Alliance Apts For The Elderly 174 AVENUE A MN 46 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House IV 538 EAST 6 STREET MN 18 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House V 234 EAST 2 STREET MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Casa Victoria Housing For The Elderly 308 EAST 8 STREET MN 80 2 Rosie Mendez Dona Petra Santiago Check Address 143 AVENUE C MN 57 2 Rosie Mendez Grand Street Senior Housing 709 EAST 6 STREET MN 78 2 Rosie Mendez Positively 3Rd Street 306 EAST 3 STREET MN 53 2 Rosie Mendez Cabrini Senior Housing 220 EAST 19 STREET MN 12 2 Rosie Mendez Renwick Gardens Apts 332 EAST 28 STREET MN 224 2 Rosie Mendez Securitad I 451 3 AVENUE MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Postgraduate Center Residence 516 WEST 50 STREET MN 22 3 Corey Johnson Associated Blind 137 WEST 23 STREET MN 210 3 Corey Johnson Clinton Gardens 404 WEST 54 STREET MN 99 3 Corey Johnson Encore West Residence 755 10 AVENUE MN 85 3 Corey Johnson Fountain House 441 WEST 47 STREET MN 21 3 Corey Johnson Capitol Apartments 834 8 AVENUE MN 285 3 Corey Johnson Yorkville Gardens 225 EAST 93 STREET MN 133 4 Daniel R. -

An Abolitionist Journal VOL

IN THE BELLY an abolitionist journal VOL. 2 JULY + BLACK AUGUST 2020 Contents Dear Comrades ������������������������������������� 4 Let’s Not Go Back To Normal ������������������������� 6 Prison in a Pandemic �������������������������������� 9 What Abolition Means to Me ������������������������� 15 Practicing Accountability ���������������������������� 16 So Describable �������������������������������������� 17 The Imprisoned Black Radical Intellectual Tradition �� 18 Cannibals ������������������������������������������� 21 8toAbolition to In The Belly Readers ���������������� 27 #8TOABOLITION ����������������������������������� 28 Abolition in Six Words ������������������������������ 34 Yes, I know you ������������������������������������� 36 Fear ������������������������������������������������ 38 For Malcolm U.S.A. ��������������������������������� 43 Are Prisons Obsolete? Discussion Questions ������������ 44 Dates in Radical History: July ����������������������� 46 Dates in Radical History: Black August �������������� 48 Brick by Brick, Word by Word ����������������������� 50 [Untitled] ������������������������������������������� 52 Interview with Abolitionist, Comrade, and IWOC Spokes- Published and Distributed by person Kevin Steele �������������������������������� 55 True Leap Press Pod-Seed / A note about mail ����������������������� 66 P.O. Box 408197 Any City USA (Dedicated to Oscar Grant) ������������ 68 Chicago, IL 60640 Resources ������������������������������������������ 69 Write for In The Belly! ������������������������������� -

Fear and Threat in Illegal America: Latinas/Os, Immigration, and Progressive Representation in Colorblind Times by Hannah Kathr

Fear and Threat in Illegal America: Latinas/os, Immigration, and Progressive Representation in Colorblind Times by Hannah Kathryn Noel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn A. Alsultany, Co-chair Associate Professor María E. Cotera, Co-chair Associate Professor María Elena Cepeda, Williams College Associate Professor Anthony P. Mora © Hannah Kathryn Noel DEDICATION for Mom & Dad ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I could not have accomplished this dissertation without the guidance of my co-chairs, and graduate and undergraduate mentors: Evelyn Alsultany, María Cotera, María Elena Cepeda, Mérida Rúa, Larry La Fountain-Stokes, Carmen Whalen, Ondine Chavoya, Amy Carroll, and Anthony Mora. Evelyn, thank you for the countless phone calls, comments on every page of my dissertation (and more), advice, guidance, kind gestures, and most of all your sensibilities. You truly went above and beyond in commenting and helping me grow as a teacher, scholar, and human. María, thank you for standing by my side in both turbulent, and joyous times; your insight and flair with words (and style) are beyond parallel. Maria Elena, thank you for your constant guidance and keen constructive criticism that has forced me to grow as an intellectual and teacher. I will never forget celebrating with you when I found out I got into Michigan, I am beyond honored and feel sincere privilege that I have been able to work and grow under your mentorship. Mérida, I would have never found my way to my life’s work if I had not walked into your class. -

Excessive Use of Force by the Police Against Black Americans in the United States

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Written Submission in Support of the Thematic Hearing on Excessive Use of Force by the Police against Black Americans in the United States Original Submission: October 23, 2015 Updated: February 12, 2016 156th Ordinary Period of Sessions Written Submission Prepared by Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Global Justice Clinic, New York University School of Law International Human Rights Law Clinic, University of Virginia School of Law Justin Hansford, St. Louis University School of Law Page 1 of 112 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary & Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Pervasive and Disproportionate Police Violence against Black Americans ..................................................................... 21 A. Growing statistical evidence reveals the disproportionate impact of police violence on Black Americans ................. 22 B. Police violence against Black Americans compounds multiple forms of discrimination ............................................ 23 C. The treatment of Black Americans has been repeatedly condemned by international bodies ...................................... 25 D. Police killings are a uniquely urgent problem ............................................................................................................. 25 II. Legal Framework Regulating the Use of Force by Police ................................................................................................ -

Part I: Introduction

Part I: Introduction “Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.” -Thomas Paine, Common Sense (1776) “For my part, whatever anguish of spirit it may cost, I am willing to know the whole truth; to know the worst and provide for it.” -Patrick Henry (1776) “I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth. On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen -- but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal, and to hasten the resurrection of the dead.” -William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator (1831) “Gas is running low . .” -Amelia Earhart (July 2, 1937) 1 2 Dear Reader, Civilization as we know it is coming to an end soon. This is not the wacky proclamation of a doomsday cult, apocalypse bible prophecy sect, or conspiracy theory society. -

1. Petitions to Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4

Disclaimer and Credit: This is by no means comprehensive, but rather a list we hope you find helpful as a starting point to begin or to continue to support our Black brothers, sisters, communities and patients. Thank you to the Student National Medical Association chapter at George Washington University School of Medicine for compiling many of these resources. Editing Guidelines: Please feel free to add any resources that you feel are useful. Any inappropriate edits will be deleted and editing capabilities will be revoked. Table of Contents 1. Petitions To Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4. Mental Health Resources 5. Anti-Racism Reading and Resource List 6. Media 7. Voter Registration and Related Information 8. How to Support Memphis 1. Petitions To Sign *Please note that should you decide to sign a petition on change.org, DO NOT donate through change.org. Rather, donate through the websites specific to the organizations to ensure your donated funds are going directly to the organization. ● Justice for George Floyd ● Justice for Breonna ● Justice for Ahmaud Arbery ● We Can’t Breathe ● Justice for George Floyd 2. Protestor Bail Funds ● National Bail Fund Network (by state) ○ This link includes links to various cities ● Restoring Justice (Legal & Social services) 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations Actions are loud. As students, we know that money is tight. But if each of us donated just $5 to one cause, together we could demand a great impact. ● Black Visions Collective (Minnesota Based): “BLVC is committed to a long term vision in which ALL Black lives not only matter, but are able to thrive.