Association of the Client-Provider Ratio with the Risk of Maternal Mortality In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

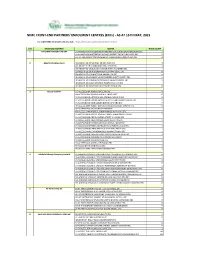

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Causes, Effect and Abatement Measures of Flooding in River Ajilosun Drainage Basin in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Donnish Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Vol 4(1) pp. 001-010 September, 2017 http://www.donnishjournals.org/djene Copyright © 2017 Donnish Journals Original Research Article Causes, Effect and Abatement Measures of Flooding in River Ajilosun Drainage Basin in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria Arohunsoro, Segun Joseph and Omotoba, Nathaniel Ileri* Department of Geography and Planning Science, Ekiti State University, P.M.B. 5363, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeira. Accepted 28th August, 2017. The paper examined causes, effect and abatement measures of flooding in River Ajilosun drainage basin in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Data were collected on morphometric variables such as channel width and channel depth which were measured with ranging pole and tie rod. Channel efficiency was derived from a mathematical relationship between the channel capacity and the wetted perimeter of the channel. Data on slopes were obtained with Abney level. Data were also obtained on distance of buildings to river valley with a tape measure. 150 copies of questionnaire were also administered systematically to landlords of houses along River Ajilosun in order to obtain information on experience and effect of flooding in the basin. The study employed both descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze the data. The outcome of the descriptive analysis revealed illegal dumping of refuse in stream channel as the principal cause of flooding in River Ajilosun. Other causes of flooding are the heavy and frequent tropical rainfall in the area. The results of the quantitative analysis showed that the geomorphological variables accounted for about 80% of the total variation in spatial extent of flooding in the drainage basin. -

Ojodu, Ishaq Bamidele

OJODU, ISHAQ BAMIDELE. Date of Birth: 2nd March, 1971. +2348178450206 +2349026701419 201, Bamgbose Street, Lagos Island, Lagos, Nigeria. [email protected] Objective: To be involved in all areas of Orthopedic and Trauma management including research that supports evidence-based high quality Orthopedic and Trauma care services. Career Profile: An Orthopedic and Trauma Surgeon delivering high quality orthopedic/trauma care to clients, in addition to finding ways to enshrine evidence based clinical practice. Education March 2012 – 2017: Postgraduate Diploma Clinical Research University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Oct. 2003 – April 2009: Fellow of West Africa College of Surgeons. FWACS (Ortho) Oct. 1990 – Feb. 1998: M.B.,B.S University of Ibadan Sept. 1983- July 1988: West African School Certificate Premier Grammar School, Abeokuta. Ogun State. Work Experience Jan 2017 –till date : Lecturer 1, Department of Surgery, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo city, Ondo State. March 2015 –till date: Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo city, Ondo State. July 2013 – July 2014: Consultant Orthopedic Surgeon, Cedarcrest Hospitals, Lagos. Aug., 2010 – June 2013: Orthopedic/Trauma Surgeon- King Khalid Civilian Hospital, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. April 2009 – July 2010: Visiting Consultant Orthopedic/Trauma Surgeon, St Nicholas Hospital, Lagos.. April 2006 – Oct., 2009: Senior Registrar, Orthopedics/Trauma- National Orthopaedic Hospital, Lagos. Jan., 2005 – March 2006: Junior Registrar, General Surgery Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Ikeja, Lagos. Oct., 2003 – Dec., 2004: Junior Registrar, Orthopedics/Trauma- National Orthopaedic Hospital, Lagos. Jan 2000 – Sept., 2003: Medical Officer – General Hospital, Lagos March 1999 – Feb., 2000: Medical Officer – (NYSC) Staff Clinic, Eti-Osa Local Govt., Ikoyi, Lagos. April 1998 – Feb., 1999: Medical Intern – St Nicholas Hospital, Lagos. -

Views of Senior Health Personnel About Quality of Emergency Obstetric Care: a Qualitative Study in Nigeria

RESEARCH ARTICLE Views of senior health personnel about quality of emergency obstetric care: A qualitative study in Nigeria Friday Okonofua1,2*, Abdullahi Randawa3☯, Rosemary Ogu4☯*, Kingsley Agholor5³, Ola Okike6³, Rukayat Adeola Abdus-salam7³, Mohammed Gana8³, Eghe Abe9³, Adetoye Durodola10³, Hadiza Galadanci11³, WHARC WHO FMOH MNCH Implementation Research Study Team1¶ a1111111111 1 Women's Health and Action Research Centre, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria, 2 University of Medical a1111111111 Sciences, Ondo City, Ondo State, Nigeria, 3 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria, 4 University a1111111111 of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria, 5 Central Hospital, Warri, Delta State, Nigeria, 6 Karshi a1111111111 General Hospital, Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, Nigeria, 7 Adeoyo Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, a1111111111 8 General Hospital, Minna, Niger State, Nigeria, 9 Central Hospital, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria, 10 General Hospital, Ijaye, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria, 11 Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano State, Nigeria ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work ¶ The full membership list of ªThe WHARC WHO FMOH MNCH Implementation Research Study Teamº is OPEN ACCESS provided in the Acknowledgments. * [email protected] (RO); [email protected] (FO) Citation: Okonofua F, Randawa A, Ogu R, Agholor K, Okike O, Abdus-salam RA, et al. (2017) Views of senior health personnel about quality of emergency obstetric care: A qualitative study in Nigeria. PLoS Abstract ONE 12(3): e0173414. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0173414 Background Editor: Animesh Biswas, Centre for Injury Late arrival in hospital by women experiencing pregnancy complications is an important Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB) & background factor leading to maternal mortality in Nigeria. -

Akeredolu Journey to Redemption

GGIANTIANT STRIDES AKEREDOLU JOURNEY TO REDEMPTION Abridged Version(First Steps and Giant Strides) 1 2 3 4 5 Abridged/Revised Version (First Steps and Giant Strides) GIANT STRIDES JOURNEY TO REDEMPTION Governor Oluwarotimi Odunayo Akeredolu(Aketi), SAN NGUHER ZAKI 6 7 contents INTRODUCTION 10 FOREWORD 12 JOB CREATION THROUGH AGRICULTURE, 14 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INDUSTRIALISATION. MASSIVE INFRASTRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT 66 AND MAINTENANACE. PROMOTION OF FUNCTIONAL EDUCATION 98 AND TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH. PROVISION OF ACCESSIBLE AND QUALITATIVE 128 HEALTH CARE AND SOCIAL SERVICE DELIVERY. RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND 160 COMMUNITY EXTENSION SERVICES. SECURITY, LAW AND ORDER. 176 ARABINRIN IN ACTION . 202 ALLIANCES AND ENGAGEMENTS. 244 8 9 This book therefore enacts itself as speak with a certain force, clarity and an institutional memory which stores power which provide answers to the and unveils – in a rhythmic, cyclical questions: When is leadership? What Introduction and unending motion, Akeredolu’s should leadership do, now? And when he being of courage and This volume is an edited collection of experience ranging from anxiety, moral tapestry in Ondo State. is the nowness of now? No air, no character at the epicentre of the vivid pictures selected from frustration, disappointments, poverty, Why a book written in pictures? It is pretence and no colour. of heroism is the defining tonnes of photographic captures gloom and statism all of which for ease of reference and colour to The intrinsic value of the evidences characteristic of true and representations -

Ondo State Pocket Factfinder

INTRODUCTION Ondo is one of the six states that make up the South West geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It has interstate boundaries with Ekiti and Kogi states to the north, Edo State to the east, Delta State to the southeast, Osun State to the northwest and Ogun State to the southwest. The Gulf of Guinea lies to its south and its capital is Akure. ONDO: THE FACTS AND FIGURES Dubbed as the Sunshine State, Ondo, which was created on February 3, 1976, has a population of 3,441,024 persons (2006 census) distributed across 18 local councils within a land area of 14,788.723 Square Kilometres. Located in the South-West geo-political zone of Nigeria, Ondo State is bounded in the North by Ekiti/Kogi states; in the East by Edo State; in the West by Oyo and Ogun states, and in the South by the Atlantic Ocean. Ondo State is a multi-ethnic state with the majority being Yoruba while there are also the Ikale, Ilaje, Arogbo and Akpoi, who are of Ijaw extraction and inhabit the riverine areas of the state. The state plays host to 880 public primary schools, and 190 public secondary schools and a number of tertiary institutions including the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State Polytechnic, Owo, Federal College of Agriculture, Akure and Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo. Arguably, Ondo is one of the most resource-endowed states of Nigeria. It is agriculturally rich with agriculture contributing about 75 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The main revenue yielding crops are cocoa, palm produce and timber. -

Kayode Ezekiel ADEWOLE. Bsc Msc Phd CONTACT ADDRESSES

CURRICULUM VITAE Kayode E. Adewole, BSc MSc PhD NAME: Kayode Ezekiel ADEWOLE. BSc MSc PhD CONTACT ADDRESSES: Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Medical Sciences Ondo State Nigeria E mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Phone: +234-8034997046 PRESENT ACADEMIC POSITION: Lecturer II, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo State Nigeria EDUCATION 2003 BSc. Biochemistry, University of Ilorin, Ilorin Nigeria 2007 MSc. Biochemistry, University of Ibadan 2017 Ph.D. Biochemistry, University of Ilorin, Ilorin Nigeria GRANT 2015-Recepient: West Africa Research Council Travel Grant Short term visit to Kintampo Health Research Centre Kintampo, Brong-Ahafo Region Ghana to conduct part of Ph.D. research ACADEMIC CAREER AND EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2013-2017 Full-time Ph.D. Programme, University of Ilorin, Ilorin Nigeria 2015 Visiting Research Fellow, West Africa Research Association (Kintampo Health Research Centre Kintampo, Brong-Ahafo Region Ghana) 2018 (1st October) - 2019 (3rd February) Lecturer II, Ajayi Crowther University Oyo, Oyo State Nigeria 2019 (February 4) Lecturer II, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo City, Ondo State Nigeria MEMBERSHIP OF LEARNED SOCIETIES (a) Member, West Africa Research Association (b) Member, Society of Toxicology (c) Associate Member, Royal Society of Chemistry TRAINING ATTENDED Bioinformatics foundational training (Africa Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases, Redeemer’s University Ede, Nigeria) 25th-29th, November 2019 CURRENT RESEARCH INTEREST exploration of phytochemicals as anticancer and antimalarial agents PUBLICATIONS (1) Adebayo JO, Adewole KE. Evaluation of cysteine-stabilised peptide fraction of aqueous extract of Morinda lucida leaf for hepatotoxic effects in mice. -

NAME of AGENCY: NATIONAL INSTITUTE for EDUCATIONAL PLANNING and ADMINISTRATION, NIEPA-Nigeria, ONDO

NAME OF AGENCY: NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR EDUCATIONAL PLANNING AND ADMINISTRATION, NIEPA-Nigeria, ONDO. 05-Nov-19 1 Hon. Biodun OMOLEYE Born on a Christmas day some years ago at the Seventh-day Adventist hospital in the great ancient town of Ile-Ife to Mr. & Mrs. M. S. Omoleye. Hon. Omoleye had his primary education at Ile-Ife and Ayede-Ekiti. He later attended Omuo Comprehensive High School, Omuo- Ekiti and later obtained his Higher School Certificate. He attended Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife where he got his Bachelor’s of Arts (B.A.) degree in History and Master of Science (Msc.) degree in International Relations. Hon. Omoleye started his working career in Lagos where he Hon. Biodun OMOLEYE worked in the Nigerian office of the British Educational Training and Technology Association as an Educational & Training Consultant. He left B.E.T.T.A to join the management of the Capital Oil Plc. 05-Nov-19 2 Hon. Biodun OMOLEYE He arose to the position of Head of International Operations of the company before leaving to set-up his own oil marketing company with friends and colleagues who pulled out at the same time from African Petroleum and General Oil limited to form ALFA Oil Limited. His interest knows no bounds, he ventured into publishing and pioneered the publication of a monthly human Development magazine called' Youth Consult'. He is also into energy management and consulting. A youth at heart, represented the interest of youths at several international fora. Hon. Biodun OMOLEYE Mr. Omoleye is also a seasoned administrator and educationist climaxing his university career at Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State where he retired from the university service as Principal Assistant Registrar in 2016. -

Spatial Regression and Geostatistics Discourse with Empirical Application to Precipitation Data in Nigeria Oluyemi A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Spatial regression and geostatistics discourse with empirical application to precipitation data in Nigeria Oluyemi A. Okunlola1, Mohannad Alobid2*, Olusanya E. Olubusoye3, Kayode Ayinde4, Adewale F. Lukman1 & István Szűcs2 In this study, we propose a robust approach to handling geo-referenced data and discuss its statistical analysis. The linear regression model has been found inappropriate in this type of study. This motivates us to redefne its error structure to incorporate the spatial components inherent in the data into the model. Therefore, four spatial models emanated from the re-defnition of the error structure. We ftted the spatial and the non-spatial linear model to the precipitation data and compared their results. All the spatial models outperformed the non-spatial model. The Spatial Autoregressive with additional autoregressive error structure (SARAR) model is the most adequate among the spatial models. Furthermore, we identifed the hot and cold spot locations of precipitation and their spatial distribution in the study area. Te ordinary least squared regression (OLS) has become a household name in many disciplines, especially when there is a need to investigate the cause and efect relationship between a response variable and one or more covariates1 . However, the reliability of OLS results depends on certain assumptions commonly called the “Gauss Assumption”. One of the stringent of these assumptions is that the error terms in the model should be independent. Te violation of this assumption in the classical regression makes the inference on the coefcient to be invalid due to infated standard error. In real-life situations, this assumption of OLS is not attainable because observations located in space are related to their nearby units 2. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Bernard B. Fyanka Phd

CURRICULUM VITAE Bernard B. Fyanka PhD A. PERSONAL DATA Name: FYANKA Bernard Bemhemba. Date of Birth: 29th June 1974 Marital Status: Married Postal Address: Department of History and International Studies Redeemer’s University. E-Mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] Mobile Phone # 08032226424 NO. of Children and their age One child, 8 years Name and Address of of Spouse: Ene Agatha Fyanka, Flat 2b 20b (17B) RUN Quarters Nationality: Nigerian State of Origin Benue State B.EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND B.1 HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS ATTENDED WITH DATE University of Lagos Akoka Nigeria. PhD History and Strategic Studies 2008-2015 University of Bergen Norway. Bergen Summer Research School University of Bergen. (BSRS 2014) Certificate in Governance to meet Global Challenges” 23rd June to 4th July 2014. University of Lagos Akoka Nigeria Masters of Arts History & Strategic Studies 2006-2008 University of Lagos Akoka Lagos Bachelor of Arts History 2nd Second Class Upper 1992-1997 Goal 2000 Computer Network Kano Certificate Desktop Publishing. March –May 1998 B2. ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Primary School Leaving Certificate 1985 Secondary School Certificate Exam 1991 Bachelor of Arts History 2nd Class Upper 1997 1 | P a g e Certificate Desktop Publishing. 1998 Masters of Arts, History & Strategic Studies 2008. Certificate in Global Governance 2014 Dr of Philosophy (PhD) History and Strategic Studies. 2015 Certificate in “Advanced Digital Appreciation Programme for Tertiary Institutions”(ADAPTI) April 2017 EQUIP Certified Trainer Certificate, EQUIP Leadership Development Series. September 2017 Certificate for Chief Executive Leadership Development Program (CELDP) RUNMAXIT John Maxwell Team in July 2018 Certificate in Curriculum Development in Critical Antisemitism Studies Institute for For the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (ISGAP) ISGAP Oxford Summer Institute 2020. -

Experiences of HIV Patients in a Tertiary Hospital in Southwest Nigeria

Science Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020; 9(3): 50-57 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/sjcm doi: 10.11648/j.sjcm.20200903.11 ISSN: 2327-2724 (Print); ISSN: 2327-2732 (Online) Patients’ Treatment Satisfaction: Experiences of HIV Patients in a Tertiary Hospital in Southwest Nigeria Osho Patrick Olanrewaju 1, *, Adepoju Omoseni Oyindamola 2, Joseph Adejoke Ajidat 3, Joseph Oluyemi 4, Ojo Oladotun Ayotunde 5, Ojo Matilda Adesuwa Osagie 1, Oni Oluwatosin Idowu 6 1Department of Haematology & Blood transfusion, Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo-City, Nigeria 2Department of Business Administration, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria 3Department of Microbial Pathology, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo, Nigeria 4Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Nelson Mandela University, Port-Elizabeth, South Africa 5Department of Physics, Biophysics and Medical Physics Unit, Osun State University, Osogbo, Nigeria 6Department of Haematology/Virology, University of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital, Akure, Nigeria Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Osho Patrick Olanrewaju, Adepoju Omoseni Oyindamola, Joseph Adejoke Ajidat, Joseph Oluyemi, Ojo Oladotun Ayotunde, Ojo Matilda Adesuwa Osagie, Oni Oluwatosin Idowu. Patients’ Treatment Satisfaction: Experiences of HIV Patients in a Tertiary Hospital in Southwest Nigeria. Science Journal of Clinical Medicine . Vol. 9, No. 3, 2020, pp. 50-57. doi: 10.11648/j.sjcm.20200903.11 Received : May 22, 2020; Accepted : June 15, 2020; Published : July 17, 2020 Abstract: According to the World Health Organization, about 40 Million people are living with HIV/ AIDS, where two- third resides in the African region and about 2 Million of them are from Nigeria. Hence, this study assessed the satisfaction of patients with services provided in a tertiary hospital in southwest Nigeria. -

Quality of Service Challenges for IP Networks

Variational Iteration Method for Solving an Infectious Disease Model A.A. Ayoade, Ph.D.*1; T.F. Aminu M.Sc.2; M.O. Ajisope, Ph.D.3; A.I. Abioye, M.Sc.4; A.A. Victor, M.Sc.4; and S. Amadiegwu, M.Sc.5 1Department of Mathematics, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo City, Ondo State, Nigeria. 2Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Federal Polytechnic, Offa, Kwara State, Nigeria. 3Department of Mathematics, Federal University, Oye-ekiti Ekiti State, Nigeria. 4Department of Mathematics, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. 5Department of Mathematics, School of General Studies, Maritime Academy of Nigeria, Oron, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]* ABSTRACT The concealed and impulsive nature of epidemic diseases has been a major source of panic and In this paper, we present a deterministic model superstitions since the beginning of human that captures the essential dynamics of infectious civilization. The global fear accompanied the diseases. Variational Iteration Method (VIM) is emergence of avian flu and SARS in Southeast applied to attempt the series solution of the Asia and Ebola in Africa are cases that our model. The efficiency of the VIM in solving the feeling of horror increases with our awareness of model is confirmed by classical fourth-order the outbreaks. One of the concerns of infectious Runge-Kutta method implemented in Maple 18. modeling is studying the transmission of diseases The comparisons between the VIM and Runge- in a host population, both in space and time. The Kutta (RK4) solutions are made and there exists first epidemiological model was credited to Daniel positive correlation between the results obtained Bernoulli in 1760 (d’Onofrio, 2002) which was by the two methods.