Matthew Rimmer Professor of Intellectual Property and Innovation Law Faculty of Law Queensland University of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LLB and JD Handbook 2010

ANU COLLEGE OF LAW THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY LLB & JD HANDBOOK 2010 This publication is intended to provide information about the ANU College of Law which is not available elsewhere. It is not intended to duplicate the 2010 Undergraduate Hand- book. It can be found on the web at http://law.anu.edu.au/Publications/llb/2010. Copies of the 2010 Undergraduate Handbook may be purchased from the University Co-op Bookshop on campus, local booksellers and some newsagents. It can be found on the Web at www.anu.edu.au/studyat. ANU College of Law | February 2010 Contents Message from the Dean. 5 Academic Calendars. 6 Staff. 8 Administrative Staff. 9 Academic Staff of the ANU College of Law . 10 Other College Administrative Staff. 12 Visiting Fellows, Distinguished Visiting Mentor, ARC Fellows, Emeritus and Adjunct Professors and Part Time Course Convenors. 13 General College Information. 14 The Dean . 14 Associate Dean, Head of School and Sub-Dean. 14 Assistant Sub-Deans. 14 College Committees . 14 The Law School Office. 15 The Services Office. 15 The Law Library. 16 The Law Students’ Society. 17 ANU Students’ Association (ANUSA). 19 Program Information. 20 Admission. 20 Prerequisites for Admission. 21 Academic Skills and Learning Centre . 22 Indigenous Australians Support Scheme. 22 International Students. 23 Scholarships. 23 Austudy/Youth Allowance. 24 Degree Requirements. 25 Bachelor of Laws (LLB). 25 Bachelor of Laws (LLB) Combined Degrees. 26 Juris Doctor (JD). 28 Bachelor of Laws (Graduate) [LLB(G)]. 30 Honours. 30 General Information relating to all ANU Law Degrees . 30 Admission and Career Information . 36 Admission to Practice. -

Houston Paparazzi

Tom Hariel & Neon Boots Office Manager Justin Bryan Earnest Mcdowell enjoying the Galloway playing pool on Sunday Texans vs. Tennessee Titans game on Sunday houston paparazzi Fun @ Neon Boots trodding the boards Pamela Robinson & friends having ...from 30 a birthday party easy, but more experienced directors don’t always pull it off this well. And she wisely guides her cast into line-readings that give some of the overwritten passages a know- ing, ironic edge. As Chandler, a young man with a big imagination who may be too smart for his own good, recent UNO graduate Mason Joiner gives a remarkable performance, projecting the requisite intelligence when talking about astronomical events and other scientific subjects. Yet he makes plain the emotional brittleness that his upbringing First night of dance lessons has engendered and Chandler’s desper- ate yearning to free himself from the stric- tures his mother has imposed. He’s like a colt with an IQ of 180 eager to play in new pastures (even if he still sleeps on Star Neon Boots Live! ~ Houston, Texas Wars sheets). I can imagine a Shivaree, who seems to have traveled the world at a young age, either a bit more earth-mothery and weatherbeaten than Ashton Akridge or, conversely, more diaphanous and gamine- like. Akridge seems to split the difference, a kind of minor league Sally Bowles with a Former Mr. BRB Craig Sanford & syrupy Southern accent, innocently seduc- Donnie Pledger-Manzano having a ing with an appealing down-to-earth pres- few before dance class ence that camouflages a toughened spine. -

LIST of MOVIES from PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from Recent to Old) *See Editing Instructions at Bottom of Document

LIST OF MOVIES FROM PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from recent to old) *See editing Instructions at bottom of document 2020: Jan – Judy Feb – Papi Chulo Mar - Girl Apr - GAME OVER, MAN May - Circus of Books 2019: Jan – Mario Feb – Boy Erased Mar – Cakemaker Apr - The Sum of Us May – The Pass June – Fun in Boys Shorts July – The Way He Looks Aug – Teen Spirit Sept – Walk on the Wild Side Oct – Rocketman Nov – Toy Story 4 2018: Jan – Stronger Feb – God’s Own Country Mar -Beach Rats Apr -The Shape of Water May -Cuatras Lunas( 4 Moons) June -The Infamous T and Gay USA July – Padmaavat Aug – (no movie night) Sep – The Unknown Cyclist Oct - Love, Simon Nov – Man in an Orange Shirt Dec – Mama Mia 2 2017: Dec – Eat with Me Nov – Wonder Woman (2017 version) Oct – Invaders from Mars Sep – Handsome Devil Aug – Girls Trip (at Westfield San Francisco Centre) Jul – Beauty and the Beast (2017 live-action remake) Jun – San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival selections May – Lion Apr – La La Land Mar – The Heat Feb – Sausage Party Jan – Friday the 13th 2016: Dec - Grandma Nov – Alamo Draft House Movie Oct - Saved Sep – Looking the Movie Aug – Fourth Man Out, Saving Face July – Hail, Caesar June – International Film festival selections May – Selected shorts from LGBT Film Festival Apr - Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (Run, Milkha, Run) Mar – Trainwreck Feb – Inside Out Jan – Best In Show 2015: Dec - Do I Sound Gay? Nov - The best of the Golden Girls / Boys Oct - Love Songs Sep - A Single Man Aug – Bad Education Jul – Five Dances Jun - Broad City series May – Reaching for the Moon Apr - Boyhood Mar - And Then Came Lola Feb – Looking (Season 2, Episodes 1-4) Jan – The Grand Budapest Hotel 2014: Dec – Bad Santa Nov – Mrs. -

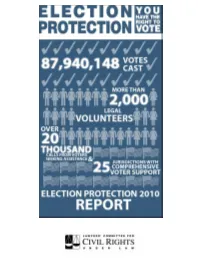

2010 Election Protection Report

2010 Election Protection Report Partners Election Protection would like to thank the state and local partners who led the program in their communities. The success of the program is owed to their experience, relationships and leadership. In addition, we would like to thank our national partners, without whom this effort would not have been possible: ACLU Voting Rights Project Electronic Frontier Foundation National Coalition for Black Civic Participation Advancement Project Electronic Privacy Information Center National Congress of American Indians AFL-CIO Electronic Verification Network National Council for Negro Women AFSCME Fair Elections Legal Network National Council of Jewish Women Alliance for Justice Fair Vote National Council on La Raza Alliance of Retired Americans Generational Alliance National Disability Rights Network American Association for Justice Hip Hop Caucus National Education Association American Association for People with Hispanic National Bar Association Disabilities National Voter Engagement Network Human Rights Campaign American Bar Association Native American Rights Fund IMPACT American Constitution Society New Organizing Institute Just Vote Colorado America's Voice People for the American Way Latino Justice/PRLDEF Asian American Justice Center Leadership Conference on Civil and Project Vote Asian American Legal Defense and Human Rights Rainbow PUSH Educational Fund League of Women Voters Rock the Vote Black Law Student Association League of Young Voters SEIU Black Leadership Forum Long Distance Voter Sierra -

March 10, 2016

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY BEFORE THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION In the Matter of: AN INQUIRY INTO THE STATE CASE NO. UNIVERSAL SERVICE FUND 2016·00059 ORDER On February 1, 2016, the Commission, on its own motion, initiated this administrative proceeding to investigate the current and future funding, distribution, and administration of the Kentucky Universal Service Fund ("KUSF") , which provides supplemental support for authorized telecommunications carriers that also participate in the federal Lifeline program. The Commission stated that the need for the investigation arose from the projected depletion of the KUSF by April 2016, at which time the fund will no longer be able to meet its monthly obligation, absent action to increase funding or reduce spending. The Commission named as parties the Attorney General's office; all Local Exchange Carriers; all commercial mobile radio service providers; and all eligible telecommunications carriers, and established a procedural schedule providing for the filing of testimony by parties, discovery, and an opportunity for a hearing. In initiating this investigation, the Commission's February 1, 2016 Order cited the need to maintain the solvency of the KUSF and proposed to either temporarily raise the KUSF per-line surcharge from $0.08 to $0.14 or to temporarily lower the amount of state support. Any comments addressing either proposal were required to be filed no later than February 22, 2016. The Commission received a total of nine joint and/or individual comments from the parties to the case, as well as three comments from members of the public. Four joint and/or individual comments 1 expressed support for the Commission's proposal to temporarily raise the per-line monthly surcharge from $0.08 to $0.14. -

2015 National Environmental Scorecard First Session of the 114Th Congress

2015 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SCORECARD FIRST SESSION OF THE 114TH CONGRESS LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS scorecard.lcv.org LCV BOARD OF DIRECTORS * JOHN H. ADAMS GEORGE T. FRAMPTON, JR. REUBEN MUNGER Natural Resources Defense Council Covington & Burling, LLP Vision Ridge Partners, LLC PAUL AUSTIN WADE GREENE, HONORARY BILL ROBERTS Conservation Minnesota & Rockefeller Family & Associates Corridor Partners, LLC Conservation Minnesota Voter Center RAMPA R. HORMEL LARRY ROCKEFELLER BRENT BLACKWELDER, HONORARY Enlyst Fund American Conservation Association Friends of the Earth JOHN HUNTING, HONORARY THEODORE ROOSEVELT IV, THE HONORABLE SHERWOOD L. John Hunting & Associates HONORARY CHAIR BOEHLERT MICHAEL KIESCHNICK Barclays Capital The Accord Group CREDO Mobile KERRY SCHUMANN THE HONORABLE CAROL BROWNER, MARK MAGAÑA Wisconsin League of Conservation Voters CHAIR GreenLatinos LAURA TURNER SEYDEL Center for American Progress PETE MAYSMITH Turner Foundation BRENDON CECHOVIC Conservation Colorado TRIP VAN NOPPEN Western Conservation Foundation WINSOME MCINTOSH, HONORARY Earthjustice CARRIE CLARK The McIntosh Foundation KATHLEEN WELCH North Carolina League of Conservation Voters WILLIAM H. MEADOWS III Corridor Partners, LLC MANNY DIAZ The Wilderness Society REVEREND LENNOX YEARWOOD Lydecker Diaz Hip Hop Caucus LCV ISSUES & ACCOUNTABILITY COMMITTEE * BRENT BLACKWELDER RUTH HENNIG KERRY SCHUMANN Friends of the Earth The John Merck Fund Wisconsin League of Conservation Voters THE HONORABLE CAROL BROWNER MARK MAGAÑA TRIP VAN NOPPEN Center for American -

LLB and JD HANDBOOK 2014 This Publication Is Intended to Provide Information About the ANU College of Law Which Is Not Available Elsewhere

ANU College of Law The Australian National University LLB AND JD HANDBOOK 2014 This publication is intended to provide information about the ANU College of Law which is not available elsewhere. This information can be found on the ANU College of Law website: > law.anu.edu.au/llb/llb-handbook It is not intended to duplicate the 2014 Undergraduate Handbook. Copies of the 2014 Undergraduate Handbook may be purchased from the University Co-op Bookshop on campus, local booksellers and some newsagents. > www.anu.edu.au/studyat. ANU College of Law | February 2014 Contents MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN ........................................... 1 ACADEMIC CALENDARS .............................................. 2 STAFF ............................................................ 4 STUDENT ADMINISTRATION ........................................... 5 ACADEMIC STAFF OF THE ANU COLLEGE OF LAW. 6 OTHER COLLEGE SENIOR PROFESSIONAL STAFF ......................... 8 VISITING FELLOWS, ADJUNCT, EMERITUS & HONORARY PROFESSORS ....... 9 GENERAL COLLEGE INFORMATION. 10 THE DEAN ......................................................... 10 DEPUTY DEAN, HEAD OF SCHOOL ..................................... 10 SUB-DEAN LLB/JD .................................................. 10 SUB-DEAN EXCHANGE & INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS .................... 10 COLLEGE COMMITTEES. 10 COLLEGE STUDENT ADMINISTRATION SERVICES ......................... 11 THE SERVICES OFFICE ............................................... 12 THE LAW LIBRARY ................................................. -

Evaluation of Comprehensive GHG Emissions Reduction Programs Outside of Washington – Final Report

Evaluation of Comprehensive GHG Emissions Reduction Programs Outside of Washington – Final Report October 21, 2013 Prepared for: State of Washington Climate Legislative and Executive Workgroup (CLEW) Prepared by: i | P a g e Final Task 2 Report Table of Contents List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ vii Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................. viii 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2 Summary Findings ............................................................................................................................. 4 3 Policy Screening and Evaluation Process Overview ..................................................................... 11 4 Cap and Trade .................................................................................................................................. 15 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 16 4.2 Literature Review of Washington Potential .............................................................................. -

LLB and JD Handbook 2011

ANU COLLEGE OF LAW THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY LLB & JD HANDBOOK 2011 This publication is intended to provide information about the ANU College of Law which is not available elsewhere. It is not intended to duplicate the 2011 Undergraduate Handbook. It can be found on the web at http://law.anu.edu.au/Publications/llb/2011. Copies of the 2011 Undergraduate Handbook may be purchased from the University Co-op Bookshop on campus, local booksellers and some newsagents. It can be found on the Web at www.anu.edu.au/studyat. ANU College of Law | February 2011 Contents Message from the Dean. 5 Academic Calendars. 6 Staff. 8 Student Administration. 9 Academic Staff of the ANU College of Law. 10 Other College Administrative Staff. .11 Visiting Fellows, Distinguished Visiting Mentor, ARC Fellows, Emeritus and Adjunct Professors and Part Time Course Convenors. 12 General College Information. 13 The Dean . 13 Associate Dean, Head of School and Sub-Dean. 13 Assistant Sub-Deans. 13 Director, Exchange And International Programs. 13 College Committees. 13 College Student Administration Services. 14 Law School Office. 14 The Services Office. 14 The Law Library. 15 The Law Students’ Society. 16 Anu Students’ Association (ANUSA). 19 Program Information. 20 Admission. 20 Prerequisites for Admission. 21 Academic Skills And Learning Centre . 22 Indigenous Australians Support Scheme. 22 International Students. 23 Scholarships. 23 Austudy/Youth Allowance . 24 Degree Requirements. 25 Normal Duration Of Programs. 25 Bachelor of Laws (LLB) . 25 Bachelor of Laws (LLB) Combined Degrees. 27 Juris Doctor (JD). 29 Bachelor of Laws (Graduate) [LLB(G)]. 31 Honours. 31 General Information Relating to all ANU Law Degrees. -

Address to the South Australian Press Club 13 July 2012

ADDRESS TO THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN PRESS CLUB 13 JULY 2012 YOU CAN’T HOLD BACK THE TIDE Ladies and gentlemen, historians give differing accounts of the story that I’m about to tell; some say it never happened at all, some say it happened elsewhere, but even if it’s apocryphal, it is nevertheless a story for our times. In the year 1028 or thereabouts, Canute, King of Denmark, England, Norway and parts of Sweden set up his throne on the tidal flats of Thorney Island, site of the current day Westminster in London, pointed his royal sceptre to the tide and uttered those immortal words: “I command thee not to rise”. Stubbornly, the tide refused to obey, and Canute’s chair, feet and royal cloak got duly soaked. When we hear this story as children we think of it as a story of human arrogance and folly. Not even Kings have that much power; Canute must have been a right royal fool. But when we hear it as adults, we know that Canute, a canny king, was reproving his courtiers and teaching them a lesson. Wise leaders, he is saying, know their power is limited, so you shouldn’t ask them to try to do the impossible. Canute was smart. But let’s assume for a moment he was truly dumb. What if he had given stopping the tide a good go? It’s possible. The technology was widely available. He could have set up a tidal review. Built a wall. And put it under the control of a publicly funded tidal regulatory body. -

John Paino Production Designer

John Paino Production Designer Selected Film and Television BIG LITTLE LIES 2 (In Post Production) Producers | Jean-Marc Vallée, Nicole Kidman, Reese Witherspoon, Per Saari, Bruna Papandrea, Nathan Ross Blossom Films Director | Andrea Arnold Cast | Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman, Reese Witherspoon, Zoë Kravitz, Adam Scott, Shailene Woodley, Laura Dern SHARP OBJECTS Producers | Amy Adams, Jean-Marc Vallée, Jason Blum, Gillian Flynn, Charles Layton, Marti Noxon, Jessica Rhoades, Nathan Ross Blumhouse Productions Director | Jean-Marc Vallée Cast | Amy Adams, Eliza Scanlen, Jackson Hurst, Reagan Pasternak, Madison Davenport BIG LITTLE LIES Producers | Jean-Marc Vallée, Nicole Kidman, Reese Witherspoon, Per Saari, Bruna Papandrea, Nathan Ross Blossom Films Director | Jean-Marc Vallée Cast | Nicole Kidman, Reese Witherspoon, Zoë Kravitz, Alexander Skarsgård, Adam Scott, Shailene Woodley, Laura Dern *Winner of [5] Emmy Awards, 2017* DEMOLITION Producers | Lianne Halfon, Thad Luckinbill, Trent Luckinbill, John Malkovich, Molly Smith, Russell Smith Black Label Media Director | Jean-Marc Vallée Cast | Jake Gyllenhaal, Naomi Watts, Chris Cooper, Polly Draper THE LEFTOVERS (Season 2 & 3) Producers | Sara Aubrey, Peter Berg, Albert Berger, Damon Lindelof, Tom Perrotta, Ron Yerxa, Tom Spezialy, Mimi Leder Warner Bros. Television Directors | Various Cast | Liv Tyler, Justin Theroux, Amy Brenneman, Amanda Warren, Regina King WILD Producers | Burna Papandrea, Reese Witherspoon Fox Searchlight Director | Jean-Marc Vallée Cast | Reese Witherspoon, Gaby Hoffmann, -

Venture with Eureka Report Pty Limited, a 100% Owned Subsidiary of News Limited

Clime Investment Management ASX ANNOUNCEMENT CLIME INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT LIMITED (ASX Code:CIW) “Clime Asset Management and Eureka Report come together to offer more wealth creation solutions” The Directors of CIW are pleased to advise shareholders that Clime has entered into a 50:50 joint venture with Eureka Report Pty Limited, a 100% owned subsidiary of News Limited. The joint venture involves Clime joining its valuation service with the online wealth creation solutions offered by Eureka Report. The Board of Clime believes this is a significant milestone for the development of our stock valuation business. Attached is a copy of the press release prepared by News Limited Richard Proctor Company Secretary Morningstar rating: The Morningstar Rating is an assessment of a fund’s past performance – based on both return and risk – which shows how similar investments compare with their competitors. A high rating alone is insufficient basis for an investment decision. Morningstar Disclaimer © 2012 Morningstar, Inc. All rights reserved. Neither Morningstar, nor its affiliates nor their content providers guarantee the above data or content to be accurate, complete or timely nor will they have any liability for its use or distribution. Any general advice has been prepared by Morningstar Australasia Pty Ltd ABN: 95 090 665 544, AFSL: 240892 (a subsidiary of Morningstar, Inc.), without reference to your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider the advice in light of these matters and, if applicable, the relevant product disclosure statement, before making any decision. Please refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at www.morningstar.com.au/fsg.pdf.