Download Transcript (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One-Word Movie Titles

One-Word Movie Titles This challenging crossword is for the true movie buff! We’ve gleaned 30 one- word movie titles from the Internet Movie Database’s list of top 250 movies of all time, as judged by the website’s users. Use the clues to find the name of each movie. Can you find the titles without going to the IMDb? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 EclipseCrossword.com © 2010 word-game-world.com All Rights Reserved. Across 1. 1995, Mel Gibson & James Robinson 5. 1960, Anthony Perkins & Vera Miles 7. 2000, Russell Crowe & Joaquin Phoenix 8. 1996, Ewan McGregor & Ewen Bremner 9. 1996, William H. Macy & Steve Buscemi 14. 1984, F. Murray Abraham & Tom Hulce 15. 1946, Cary Grant & Ingrid Bergman 16. 1972, Laurence Olivier & Michael Caine 18. 1986, Keith David & Forest Whitaker 21. 1979, Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver 22. 1995, Robert De Niro & Sharon Stone 24. 1940, Laurence Olivier & Joan Fontaine 25. 1995, Al Pacino & Robert De Niro 27. 1927, Alfred Abel & Gustav Fröhlich 28. 1975, Roy Scheider & Robert Shaw 29. 2000, Jason Statham & Benicio Del Toro 30. 2000, Guy Pearce & Carrie-Anne Moss Down 2. 2009, Sam Worthington & Zoe Saldana 3. 2007, Patton Oswalt & Iam Holm (voices) 4. 1958, James Stuart & Kim Novak 6. 1974, Jack Nicholson & Faye Dunaway 10. 1982, Ben Kingsley & Candice Bergen 11. 1990, Robert De Niro & Ray Liotta 12. 1986, Sigourney Weaver & Carrie Henn 13. 1942, Humphrey Bogart & Ingrid Bergman 17. -

The Muppets (2011

The Muppets (2011. Comedy. Rated PG. Directed by James Bobin) A Muppet fanatic and two humans in a budding relationship mobilize the Muppets, now scattered all over the world, to help save the Muppets’ beloved theater from being torn down. Songs, laughter tears ensue. Starring Jason Segel, Amy Adams, Chris Cooper, Steve Whitmire, Eric Jacobsen, David Goelz, Bill Barretta. The scenes of Kermit and friends driving across the country are in Tahoe (standing in for the snowy Rocky Mountains) and rural Lincoln in Western Placer County along Wise Road and various cross streets (standing in as the Midwest). Notice the beautiful, green fields along the roadways. \ Some of the road views can be seen from inside Kermit’s car, looking out. Other scenes feature the exterior of the car driving down county roads. The Muppets shot here in part because Placer County diverse terrain is a good substitute for many parts of the US; many other productions have done the same. This was the second time Kermit shot in Placer County. He filmed here for a few days in 2006, for a Superbowl commercial for the Ford Escape Hybrid (at Euchre Bar Tail Head/Iron Point near Alta, CA). Phenomenon (1996. Romantic fantasy. Rated PG. Directed by Jon Turteltaub) An amiable ordinary man of modest ambitions in a small town is inexplicably transformed into a genius. Starring John Travolta, Kyra Sedgewick, Forest Whitaker, and Robert Duvall. 90% of this film was shot in around Auburn, CA in 1995. Some of the locations include the Gold Country Fairgrounds, Machado’s Orchards, and various businesses in Old Town Auburn. -

CPY Document

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Offce of the City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council APR 1 2 200l Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C.D.No.13! SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk FOREST WHITAKER RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square northerly of and between numbered locations 32K and 21K as shown on Sheet 8 of Plan P-35375 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Forest Whitaker at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce of the Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date ofthe ceremony on April 16, 2007. FISCAL IMP ACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRASM1TT ALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated March 26, 2007, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council - 2 - C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee ofthe Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Forest Whitaker. The ceremony is scheduled for Monday,April 16, 2007 at 11 :30 a.m. The communicant's request is in aecordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

SHIRLEY MACLAINE to RECEIVE 40Th AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

SHIRLEY MACLAINE TO RECEIVE 40th AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD America’s Highest Honor for a Career in Film to be Presented June 7, 2012 LOS ANGELES, CA, October 9, 2011 – Sir Howard Stringer, Chair of the American Film Institute’s Board of Trustees, announced today the Board’s decision to honor Shirley MacLaine with the 40th AFI Life Achievement Award, the highest honor for a career in film. The award will be presented to MacLaine at a gala tribute on Thursday, June 7, 2012 in Los Angeles, CA. TV Land will broadcast the 40th AFI Life Achievement Award tribute on TV Land later in June 2012. The event will celebrate MacLaine’s extraordinary life and all her endeavors – movies, television, Broadway, author and beyond. "Shirley MacLaine is a powerhouse of personality that has illuminated screens large and small across six decades," said Stringer. "From ingénue to screen legend, Shirley has entertained a global audience through song, dance, laughter and tears, and her career as writer, director and producer is even further evidence of her passion for the art form and her seemingly boundless talents. There is only one Shirley MacLaine, and it is AFI’s honor to present her with its 40th Life Achievement Award." Last year’s AFI Tribute brought together icons of the film community to honor Morgan Freeman. Sidney Poitier opened the tribute, and Clint Eastwood presented the award at evening’s end. Also participating were Casey Affleck, Dan Aykroyd, Matthew Broderick, Don Cheadle, Bill Cosby, David Fincher, Cuba Gooding, Jr., Samuel L. Jackson, Ashley Judd, Matthew McConaughey, Helen Mirren, Rita Moreno, Tim Robbins, Chris Rock, Hilary Swank, Forest Whitaker, Betty White, Renée Zellweger and surprise musical guest Garth Brooks. -

Matthew Mcduffie

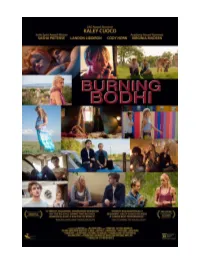

2 a monterey media presentation Written & Directed by MATTHEW MCDUFFIE Starring KALEY CUOCO SASHA PIETERSE CODY HORN LANDON LIBOIRON and VIRGINIA MADSEN PRODUCED BY: MARSHALL BEAR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: DAVID J. MYRICK EDITOR: BENJAMIN CALLAHAN PRODUCTION DESIGNER: CHRISTOPHER HALL MUSIC BY: IAN HULTQUIST CASTING BY: MARY VERNIEU and LINDSAY GRAHAM Drama Run time: 93 minutes ©2015 Best Possible Worlds, LLC. MPAA: R 3 Synopsis Lifelong friends stumble back home after high school when word goes out on Facebook that the most popular among them has died. Old girlfriends, boyfriends, new lovers, parents… The reunion stirs up feelings of love, longing and regret, intertwined with the novelty of forgiveness, mortality and gratitude. A “Big Chill” for a new generation. Quotes: “Deep, tangled history of sexual indiscretions, breakups, make-ups and missed opportunities. The cinematography, by David J. Myrick, is lovely and luminous.” – Los Angeles Times "A trendy, Millennial Generation variation on 'The Big Chill' giving that beloved reunion classic a run for its money." – Kam Williams, Baret News Syndicate “Sharply written dialogue and a solid cast. Kaley Cuoco and Cody Horn lend oomph to the low-key proceedings with their nuanced performances. Virginia Madsen and Andy Buckley, both touchingly vulnerable. In Cuoco’s sensitive turn, this troubled single mom is a full-blooded character.” – The Hollywood Reporter “A heartwarming and existential tale of lasting friendships, budding relationships and the inevitable mortality we all face.” – Indiewire "Honest and emotionally resonant. Kaley Cuoco delivers a career best performance." – Matt Conway, The Young Folks “I strongly recommend seeing this film! Cuoco plays this role so beautifully and honestly, she broke my heart in her portrayal.” – Hollywood News Source “The film’s brightest light is Horn, who mixes boldness and insecurity to dynamic effect. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Denis Villeneuve Director / Screenwriter ————— FILMOGRAPHY

Denis Villeneuve Director / Screenwriter ————— FILMOGRAPHY Blade Runner 2049 To be released October 6, 2017 Feature film Director Dune in development Feature film Director The Son in development Feature film Director Arrival 2016 Feature film Director AWARDS Academy Awards - Won Oscar Best Achievement in Sound Editing Sylvain Bellemare - Nominated Oscar Best Motion Picture of the Year Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder, David Linde/ Best Achievement in Directing Denis Villeneuve/ Best Adapted Screenplay Eric Heisserer/ Best Achievement in Cinematography Bradford Young/ Best Achievement in Film Editing Joe Walker/ Best Achievement in Sound Mixing Bernard Gariépy Strobl, Claude La Haye/ Best Achievement in Production Design Patrice Vermette (production design), Paul Hotte (set decoration), 2017, USA BAFTA Awards - Won, BAFTA Film Award Best Sound Claude La Haye, Bernard Gariépy Strobl, Sylvain Bellemare/ Nominated BAFTA Film Award Best Film Dan Levine, Shawn Levy, David Linde, Aaron Ryder/ Best Leading Actress Amy Adams/ Nominated David Lean Award for Direction Denis Villeneuve/ Nominated, BAFTA Film Award Best Screenplay (Adapted) Eric Heisserer/ Best Cinematography Bradford Young/ Best Editing Joe Walker/ Original Music Jóhann Jóhannsson/ Best Achievement in Special Visual Effects Louis Morin, UK, 2017 AFI Awards – Won AFI Awards for Movie of the Year, USA, 2017 ARRIVAL signals cinema's unique ability to bend time, space and the mind. Denis Villeneuve's cerebral celebration of communication - fueled by Eric Heisserer's monumental script - is grounded in unstoppable emotion. As the fearless few who step forward for first contact, Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner and Forest Whitaker prove the imperative for finding a means to connect - with awe- inspiring aliens, nations in our global community and the knowledge that even the inevitable loss that lies ahead is worth living. -

Abel Ferrara Jaeger-Lecoultre Glory To

La Biennale di Venezia / 77th Venice International Film Festival American director Abel Ferrara awarded the Jaeger-LeCoultre Glory to the Filmmaker 2020 prize His new film Sportin’ Life to be presented Out of Competition La Biennale di Venezia and Jaeger-LeCoultre are pleased to announce that the American director Abel Ferrara (Pasolini, Bad Lieutenant, King of New York) is the recipient of the Jaeger-LeCoultre Glory to the Filmmaker award of the 77th Venice International Film Festival (September 2 - 12, 2020), dedicated to a personality who has made a particularly original contribution to innovation in contemporary cinema. The award ceremony for Abel Ferrara will take place on Saturday September 5th 2020 in the Sala Grande (Palazzo del Cinema) at 2 pm, before the screening Out of Competition of his new film, the documentary Sportin’ Life (Italy, 65') with Abel Ferrara, Willem Dafoe, Cristina Chiriac, Anna Ferrara, Paul Hipp, Joe Delia. With regards to this acknowledgment, the Director of the Venice Film Festival Alberto Barbera has stated: “One of the many merits of Abel Ferrara, who is widely held in esteem despite his reputation as one of the most controversial filmmakers in contemporary cinema, is his undeniable consistency and allegiance to his personal approach, inspired by the principles of independent cinema even when the director had the opportunity to work on more traditional productions. From his first low-budget films, influenced directly by the New York scene populated by immigrants, artists, musicians, students and drug addicts, through his universally recognized masterpieces – The King of New York (1990), Bad Lieutenant (1992) and Body Snatchers (1994) – to his most recent works, increasingly introspective and autobiographical, Ferrara has brought to life a personal and exclusive universe. -

All the Fun of the Fare

FEATURE FoCUS n MArkEt bUzz n AlliAnCE FilMS n CnC n zEntropA n EUropE’S FilM tAx CrEditS n SightSEErS (Clockwise from left) Speranza13 Media’s Romeo & Juliet; Recreation’s Red Hook Summer; Jennifer Lawrence; Arnold Schwarzenegger; Exclusive Media’s Look Of Love; Matt Damon; Kristen Stewart; Liam Hemsworth All the fun of the fare As the Cannes Marché opens for business, Screen looks at the hottest titles debuting at the market — at all stages of production — from the US, Europe and across Asia US sellers thriller Lone Survivor, which starts shooting Sep- tional and along with head of sales Nadine de Bar- tember 15. ros will take point on the Robert Rodriguez duo By Jeremy Kay Panorama Media, the new player backed by Frank Miller’s Sin City: A Dame To Kill For in 3D Lionsgate’s Patrick Wachsberger and Helen Lee Megan Ellison and run by Marc Butan and sales and Machete Kills (both in pre-production). Kim will kick off pre-sales on Catching Fire, the head Kim Fox, will introduce buyers to Kathryn Camela Galano’s Speranza13 Media will show a aptly named sequel to this year’s $625m-plus Bigelow’s Osama Bin Laden project Zero Dark promo from Romeo & Juliet based on Julian Fel- indie global behemoth The Hunger Games. The Thirty, currently shooting. lowes’ adapted screenplay. Hailee Steinfeld from merger with Summit has added thriller Red 2 (in Stuart Ford and sales chief Jonathan Deckter of True Grit stars alongside Douglas Booth. pre-production) to the pipeline. Other hot titles IM Global arrive on the Croisette with Robert The Solution Entertainment Group principal are Roman Polanski’s thriller D and Denis Ville- Luketic’s corporate espionage thriller Paranoia, to Lisa Wilson arrives with thriller Grand Piano neuve’s Prisoners. -

“He'll Just Be Paul Newman Anyway”: Cinematic Continuity and the Star

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2018 “HE’LL JUST BE PAUL NEWMAN ANYWAY”: CINEMATIC CONTINUITY AND THE STAR IMAGE William Guy Spriggs University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0913-3382 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2018.423 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spriggs, William Guy, "“HE’LL JUST BE PAUL NEWMAN ANYWAY”: CINEMATIC CONTINUITY AND THE STAR IMAGE" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--English. 82. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/82 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Salsa2bills 1..4

By:AADukes H.R.ANo.A699 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, A state replete with diverse landscapes, iconic 2 American legends, and talented residents, Texas has long been a 3 favorite location for motion picture and television productions, 4 and that rich and ongoing tradition is being celebrated on Texas 5 Film Industry Day, which is taking place at the State Capitol on 6 March 6, 2007; and 7 WHEREAS, More than 1,500 films and television programs have 8 been made in Texas since 1910, and the first movie ever to win the 9 Academy Award for Best Picture, the silent World War I epic Wings, 10 was shot in and around San Antonio; and 11 WHEREAS, Audiences all over the world have discovered the 12 Lone Star State through films and television programs made here; 13 Giant, filmed near Marfa, tells the sprawling story of cattle and 14 oil in West Texas; no less than three films about the siege of the 15 Alamo have been made in Texas, including John Wayne 's 1960 epic The 16 Alamo; the film and television series Friday Night Lights tell the 17 distinctively Texan story of high school football; and week after 18 week Austin City Limits brings the best of American popular music to 19 the nation with a Texas flair; and 20 WHEREAS, Great filmmakers from all over the world have 21 journeyed to Texas to make their films; Steven Spielberg shot his 22 first feature, The Sugarland Express, here; Sam Peckinpah filmed 23 his classic thriller The Getaway in El Paso; Clint Eastwood has made 24 several films in Texas, including A Perfect World and Space 80R9767 JGH-D 1 -

Academy Award Winners Academy Award WINNERS

Academy Award Winners Academy award WINNERS BEST Actress 1970-2013 BEST Actor 1970-2013 ☐ Patton (1970) George C. Scott ☐ Women in Love (1970) Glenda Jackson ☐ The French Connection (1971) Gene Hackman ☐ Klute (1971) Jane Fonda ☐ The Godfather (1972) Marlon Brando ☐ Cabaret (1972) Liza Minnelli ☐ Save the Tiger (1973) Jack Lemmon ☐ A Touch of Class (1973) Glenda Jackson ☐ Harry and Tonto (1974) Art Carney ☐ Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) Ellen Burstyn ☐ ☐ One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) Louise Fletcher One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) Jack Nicholson ☐ Network (1976) Peter Finch ☐ Network (1976) Faye Dunaway ☐ The Goodbye Girl (1977) Richard Dreyfuss ☐ Annie Hall (1977) Diane Keaton ☐ Coming Home (1978) Jon Voight ☐ Coming Home (1978) Jane Fonda ☐ Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) Dustin Hoffman ☐ Norma Rae (1979) Sally Field ☐ Raging Bull (1980) Robert De Niro ☐ Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980) Sissy Spacek ☐ On Golden Pond (1981) Henry Fonda ☐ On Golden Pond (1981) Katherine Hepburn ☐ Gandhi (1982) Ben Kingsley ☐ Sophie’s Choice (1982) Meryl Streep ☐ Tender Mercies (1983) Robert Duvall ☐ Terms of Endearment (1983) Shirley MacLaine ☐ Amadeus (1984) F. Murray Abraham ☐ Places in the Heart (1984) Sally Field ☐ Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985) William Hurt ☐ The Trip to Bountiful (1985) Geraldine Page ☐ The Color of Money (1986) Paul Newman ☐ Children of a Lesser God (1986) Marlee Matlin ☐ Wall Street (1987) Michael Douglas ☐ Moonstruck (1987) Cher ☐ Rain Man (1988) Dustin Hoffman ☐ The Accused (1988) Jodie Foster ☐ My Left Foot (1989)