BAN Comments on Swiss-Ghanaian Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED NATIONS UNEP /BC/COP.3/14 Distr.: General 18 January 2020 English and French Only

UNITED NATIONS UNEP /BC/COP.3/14 Distr.: General 18 January 2020 English and French only COP3 to the Bamako Convention Third Conference of the Parties to the Bamako Convention on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa Brazzaville, Congo 12 - 14 February 2020 Report of the Secretariat on the implementation of the Bamako Convention A. Introduction 1. The Bamako Convention on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa (Bamako Convention) is a treaty of African nations whose purposes are to: prohibit the import of all hazardous and radioactive wastes into the African continent; minimize and control transboundary movements of hazardous wastes within the African continent; prohibit all ocean and inland water dumping or incineration of hazardous wastes; ensure that disposal of wastes is conducted in an “environmentally sound manner"; promote cleaner production over the pursuit of a permissible emissions approach based on assimilative capacity assumptions; and establish the precautionary principle. B. Strategic Matters 2. The Secretariat of the Bamako Convention would like to report to the Conference of the Parties the activities carried out by the Secretariat pursuant to Article 16. Illicit trafficking of hazardous waste to Africa 3. Article 16 (1) of the Bamako Convention mandates the Secretariat to, inter alia, assist Parties in their identification of cases of illegal traffic and to circulate immediately to the Parties concerned any information it has received regarding illegal traffic. 4. The was a case of illicit and illegal import of atrazine from Europe to an African country that is a party to the Bamako Convention. -

The Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes: a Comparison Between the Basel and the Bamako Conventions

International and European Law Faculty of Law, Tilburg University The Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes: a Comparison between the Basel and the Bamako Conventions Elena Faga Anr: 359993 Thesis Supervisor: Dr. J. L. Reynolds Second Reader: Ms. M. Jafroudi July 2016 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 4 I CHAPTER ...................................................................................................................................... 8 GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE TRANSBOUNDARY MOVEMENT OF WASTES ................. 8 1.1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 8 1.2. Definitions of Waste ................................................................................................................ 9 1.2.1 Hazardous waste .............................................................................................................. 10 1.3. Treatment of waste ................................................................................................................ 12 1.3.1. Disposal .......................................................................................................................... 13 1.4. Transboundary movement of wastes ..................................................................................... 13 1.4.1. Cases of illegal shipment of hazardous wastes .............................................................. -

Natural and Human Induced Hazards and Environmental Waste Management

CONTENTS NATURAL AND HUMAN INDUCED HAZARDS AND ENVIRONMENTAL WASTE MANAGEMENT Natural and Human Induced Hazards and Environmental Waste Management Volume 1 e-ISBN: 978-1-84826-299-7 ISBN : 978-1-84826-749-7 No. of Pages: 468 Natural and Human Induced Hazards and Environmental Waste Management Volume 2 e-ISBN: 978-1-84826-300-0 ISBN : 978-1-84826-750-3 No. of Pages: 370 Natural and Human Induced Hazards and Environmental Waste Management Volume 3 e-ISBN: 978-1-84826-301-7 ISBN : 978-1-84826-751-0 No. of Pages: 554 Natural and Human Induced Hazards and Environmental Waste Management Volume 4 e-ISBN: 978-1-84826-302-4 ISBN : 978-1-84826-752-7 No. of Pages: 376 For more information of e-book and Print Volume(s) order, please click here Or contact : [email protected] NATURAL AND HUMAN INDUCED HAZARDS AND ENVIRONMENTAL WASTE MANAGEMENT CONTENTS VOLUME I Hazardous Waste 1 Grasso, D, Picker Engineering Program, Smith College, Northampton, MA 10163, USA Kahn, D,Picker Engineering Program, Smith College, Northampton, MA 10163, USA Kaseva, M. E, Department of Environmental Engineering, University College of Lands and Architectural Studies (UCLAS), Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Mbuligwe, S. E, Department of Environmental Engineering, University College of Lands and Architectural Studies (UCLAS), Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 1. Definition of Hazardous Wastes 2. Sources of Hazardous Wastes 3. Classification of Hazardous Waste 4. Public Health and Environmental Effects of Hazardous Wastes 5. Hazardous Waste Management 6. Industrial Hazardous Waste Management 7. Final Disposal of Industrial Hazardous Wastes 8. Site Remediation and Groundwater Decontamination Activities 9. -

The Parties to This Convention, 1. Mindful of the Growing Threat To

BAMAKO CONVENTION ON THE BAN OF THE IMPORT INTO AFRICA AND THE CONTROL OF TRANSBOUNDARY MOVEMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF HAZARDOUS WASTES WITHIN AFRICA PREAMBLE The Parties to this Convention, 1. Mindful of the growing threat to health and the environment posed by the increased generation and the complexity of hazardous wastes, 2. Further mindful that the most effective way of protecting human health and the environment from the dangers posed by such wastes is the reduction of their generation to a minimum in terms of quantity and/or hazard potential. 3. Aware of the risk of damage to human health and the environment caused by transboundary movements of hazardous wastes, 4. Reiterating that States should ensure that the generator should carry out his responsibilities with regard to the transport and disposal of hazardous wastes in a manner that is consistent with the protection of human health and environment, whatever the place of disposal, 5. Recalling relevant Chapters of the Charter of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) on environmental protection, the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, Chapter IX of the Lagos Plan of Action and other Recommendations adopted by the Organization of African Unity on the environment, 6. Further recognizing the sovereignty of States to ban the importation into, and the transit through, their territory, of hazardous wastes and substances for human health and environmental reasons, 7. Recognizing also the increasing mobilization in Africa for the prohibition of transboundary movements of hazardous wastes and their disposal in African countries, 8. Convinced that hazardous wastes should, as far as is compatible with environmentally sound and efficient management, be disposed in the State where they were generated, 9. -

Understanding-E-Stewards-Trade

00 UNDERSTANDING E-STEWARDS IMPORT, EXPORT & TRANSIT REQUIREMENTS UNDERSTANDING E-STEWARDS IMPORT, EXPORT, & TRANSIT REQUIREMENTS CONTENTS Which Laws & Agreements Are we Talking About? .............................. 1 The Basel Convention ........................................................................... 1 The Purpose of the Basel Convention ............................................... 1 How does Basel Define hazardous waste? ........................................ 1 Problematic Components & Materials (PCMs) ................................. 1 Who are the ‘Parties’ to the Basel Convention? ............................... 1 Party to non-Party Trade Prohibition in Basel................................... 1 What is the Basel Ban Amendment? ..................................................... 2 How do the Basel Ban Amendment & Basel Convention apply to e- Stewards?.............................................................................................. 2 How do we Determine which Laws and Agreements Apply to e- Stewards? ......................................................................................... 2 Applying Basel to e-Stewards Imports .............................................. 2 Applying Basel to e-Stewards Exports ............................................... 2 Acceptable Exports & Imports, if legal .................................................. 3 Transboundary Movements for Reuse.............................................. 3 Transboundary Movements of Cleaned CRT Cullet ......................... -

The International Effort to Control the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Waste: the Basel and Bamako Conventions

THE INTERNATIONAL EFFORT TO CONTROL THE TRANSBOUNDARY MOVEMENT OF HAZARDOUS WASTE: THE BASEL AND BAMAKO CONVENTIONS Daniel Jaffe* I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 123 II. THE SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM ............................................ 125 III. THE BASEL CONVENTION ................................................. 126 IV. THE BAMAKO CONVENTION .............................................. 130 V. THE FLAWS IN THE BASEL AND BAMAKO C ONVENTIONS .............................................................. 133 VI. THE AUTHOR'S RECOMMENDATIONS ................................... 136 V II. C ONCLUSION ................................................................ 137 I. INTRODUCTION In 1986, a ship named the Khian Sea set sail from Philadelphia carrying nearly 14,000 tons of toxic incinerator ash.' The ship was unable to dispose of the ash at her first destination, the Bahamian port of Ocean Cay.2 The ship then went to Honduras, Panama, and Guinea-Bisseau, only to be rejected.' Finally, the Haitian Department of Commerce issued an import permit to the Khian Sea allowing it to dispose of its cargo.4 The Haitian Government, however, rescinded the permit after the ship unloaded between 2000 and 4500 tons of ash., Apparently, the Haitian Government initially was under the impression the ship was going to be * B.A., 1994, Florida State University; candidate for Juris Doctor, 1997, Nova Southeastern University, Shepard Broad Law Center. The author wants to express his appreciation to J. Craig -

Law of Treaties and the Export of Hazardous Waste

UCLA UCLA Journal of Environmental Law and Policy Title The Law of Treaties and the Export of Hazardous Waste Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68p0095j Journal UCLA Journal of Environmental Law and Policy, 12(2) Author Vu, Hao-Nhien Q. Publication Date 1994 DOI 10.5070/L5122018820 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Law of Treaties and the Export of Hazardous Waste Hao-Nhien Q. Vu* INTRODUCTION The public generally sees toxic waste exports as a wrong, not a legitimate activity. This perception is due, in part, to reports in- dicating a pattern in which a rich country dumps its hazardous wastes in a Third World country, often in an unsafe manner and without properly informing the local community. Accounts of such misdeeds abound. In one notorious case, the ship Khian Sea left Philadelphia in 1986 carrying twenty-eight million pounds of toxic incinerator ash. Misinforming Haiti that the ship carried "fertilizer ash," the ship's operators dumped 3000 tons of hazardous waste on the beach at Gonaives before the Haitian government rescinded per- mission.' The Khian Sea then wandered about the oceans for eighteen months, changed its name twice, changed its country of registration at least as many times, and finally showed up in Sin- gapore as the Pelicano with its cargo empty.2 The ship's opera- tors told reporters that they had legally disposed of the ash,3 and later repeated that story to a U.S. federal grand jury.4 They were * Law Clerk to United States District Judge Linda H. -

A Case Against E-Waste

A Case against E-Waste: Where One Country’s Trash is (Not) Another Country’s Treasure: Developing National E-Waste Legislation to Regulate E-Waste Exportation By Dominique C. French B.A., May 2007, University of South Florida J.D., May 2010, University of Baltimore School of Law A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of The George Washington University Law School in partial satisfaction of the requirements of for the degree of Masters of Laws January 31, 2012 Thesis directed by Dean Lee Paddock Associate Dean for Environmental Studies Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank her parents for their support and love throughout the law school process. She never would have made it through without them. ii Abstract A Case Against E-Waste: Where One Country's Trash is Not Another Country's Treasure: Developing National E-Waste Legislation to Regulate E-Waste Exportation Over the past decade, the proliferation of electronic devices in the waste stream has caused an increase in exportation of used electronics to third world countries. As a result of this exportation, several health and environmental issues have manifested. A large percentage of these wastes are shipped to third world countries where the devices are improperly disposed of either through burning or open disposal. The result of such improper disposal is the release of toxic constituents in to the environment. This paper delves in to detail about the toxicity of electronic components, and examines the health and environmental effects of improper disposal of e-waste in third world countries. After discussing the negative implications that improper disposal of e-waste, the paper will examine the current state and local laws that the United States has regarding e-waste disposal, and will discuss the inherent inadequacies. -

Bamako Convention on the Ban of the Import Into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes Within Africa, 1991

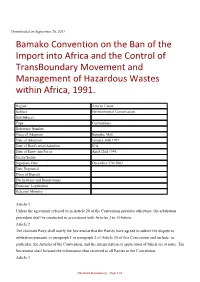

Downloaded on September 26, 2021 Bamako Convention on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of TransBoundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa, 1991. Region African Union Subject Environmental Conservation Sub Subject Type Conventions Reference Number Place of Adoption Bamako, Mali Date of Adoption January 30th 1991 Date of Ratification/Adoption N/A Date of Entry into Force April 22nd 1998 Treaty Status Signature Date December 17th 2003 Date Deposited Place of Deposit Declarations and Reservations Domestic Legislation Relevant Ministry Article 1 Unless the agreement referred to in Article 20 of the Convention provides otherwise, the arbitration procedure shall be conducted in accordance with Articles 2 to 10 below. Article 2 The claimant Party shall notify the Secretariat that the Parties have agreed to submit the dispute to arbitration pursuant to paragraph 1 or paragraph 2 of Article 20 of this Convention and include, in particular, the Articles of the Convention, and the interpretation or application of which are at issue. The Secretariat shall forward the information thus received to all Parties to the Convention. Article 3 http://www.kenyalaw.org . Page 1/34 The arbitral tribunal shall consist of three members. Each of the Parties to the dispute shall appoint an arbitrator, and the two arbitrators 80 appointed shall designate by common agreement the third arbitrator, who shall be the chairman of the tribunal. The latter shall not be a national of one of the parties to the dispute, nor have his usual place of residence in one of the Parties, nor be employed by any of them, nor have dealt with the case in any other capacity. -

Summary of BAN's Alternative E-Waste Guideline the Basic Rule

Summary of BAN's Alternative e-Waste Guideline The basic rule when determining whether used electronics can be managed as waste or non-waste is based on a requirement for pre-export functionality testing. Notwithstanding the conditional exception outlined below, under BAN’s Responsible Guideline if used electronic equipment is to be exported it must be tested and declared as fully functional. If it is untested or not fully functional it must be managed as a waste. This basic rule applies, unless all States concerned (exporting, importing or transit) have pre-notified the Basel Convention Secretariat that they wish to exercise the conditional exception found in the Responsible Guideline, and that they have pre-approved and listed the designated exporters or repair facilities that can legally accomplish the trade in an environmentally sound manner and in a manner which respects the Basel Ban Amendment. In this way all States Concerned are in agreement and there is transparency as to the responsible exporters and facilities involved. Further, this export for repair, refurbishment or failure analysis exception is only allowed for: a. Professional (e.g. medical, scientific, specialty) IT Equipment; or b. Qualified Consumer IT equipment, (not containing cathode ray tubes, mercury, PCBs or asbestos). Any failure to follow the procedures outlined in the Responsible Guideline would mean that the equipment in question is a waste and it would be subject to the rules regarding criminal trafficking in hazardous waste found in the Basel Convention. Differences Between the Official and the Responsible Guidelines on the Transboundary Movement of Used Electronic Equipment "Official" Basel BAN's Responsible Issue Guideline Guideline Default policy on A claim of "Repair" can The basic rule is that non- determining waste from allow exporters to avoid functional equipment is non-waste for electronics waste. -

The Synergy of Chemical Conventions; Opportunities and Obstacles - an NGO Perspective

The Synergy of Chemical Conventions; Opportunities and Obstacles - an NGO Perspective For many public interest non-government organizations (NGOs), the challenge of effective synergistic implementation of the chemical conventions is far from simply a policy issue. The growing urgency of the chemical body burden in humans and wildlife require us to support initiatives to improve chemical management and reduce the global chemical load. Chemical contamination of the environment shows no respect for territorial borders and therefore countries on their own, cannot respond effectively. The coordinated implementation of chemical multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) can provide real opportunities for full life cycle management of chemicals at a national, regional and international level. There are opportunities for coordination and harmonization in policy, information management, technical skills, capacity building and training, as well as legislation. The synergy between the chemical MEAs is one way of building effective international and regional frameworks to minimise and prevent the impacts of toxic chemicals and hazardous waste. This paper will provide an NGO perspective on the interlinkages and synergies between the chemical conventions and the obstacles to their combined implementation. It makes recommendations in priority areas for international capacity building initiatives and provides` a South Pacific case study in legislative synergies. The paper draws on the experience of the authors1 in capacity building initiatives and legislative development in chemical management, in Australia, the Pacific region and internationally. While it outlines the benefits of synergy, it will also focus on the challenges faced by countries attempting the combined implementation of a selection of international or regional chemical instruments. Priority International Chemical Instruments There are many chemical conventions and agreements to consider, both internationally and regionally. -

BAMAKO CONVENTION on the Ban of the Import Into Africa and The

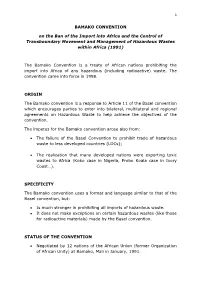

1 BAMAKO CONVENTION on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa (1991) The Bamako Convention is a treaty of African nations prohibiting the import into Africa of any hazardous (including radioactive) waste. The convention came into force in 1998. ORIGIN The Bamako convention is a response to Article 11 of the Basel convention which encourages parties to enter into bilateral, multilateral and regional agreements on Hazardous Waste to help achieve the objectives of the convention. The impetus for the Bamako convention arose also from: • The failure of the Basel Convention to prohibit trade of hazardous waste to less developed countries (LDCs); • The realization that many developed nations were exporting toxic wastes to Africa (Koko case in Nigeria, Probo Koala case in Ivory Coast…). SPECIFICITY The Bamako convention uses a format and language similar to that of the Basel convention, but: • Is much stronger in prohibiting all imports of hazardous waste. • It does not make exceptions on certain hazardous wastes (like those for radioactive materials) made by the Basel convention. STATUS OF THE CONVENTION • Negotiated by 12 nations of the African Union (former Organization of African Unity) at Bamako, Mali in January, 1991. 2 • Came into force in 1998. • To date: 29 Signatories, 25 Parties • Held its first Conference of Parties in June 2013 at Bamako, Mali. PURPOSE OF THE CONVENTION • Prohibit the import of all hazardous and radioactive wastes into the African continent for any reason; • Minimize and control transboundary movements of hazardous wastes within the African continent.