New York Premiere of Restored Version of One from the Heart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Presumed Innocent Free Ebook

FREEPRESUMED INNOCENT EBOOK Scott Turow | 432 pages | 01 Apr 2010 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141049212 | English | London, United Kingdom Presumed Innocent by Scott Turow | Hachette Book Group I n the final days before the Senate vote on the confirmation of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, the national debate over the right course of action was distilled into one key Presumed Innocent Whom to believe? The hearing process provided a stage for the striking testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who accuses Kavanaugh of sexual assault when Presumed Innocent were in high school, and the emotional rebuttal of Kavanaugh, who denies those claims. The news has also drawn attention to a fundamental principle of law that, it turns out, is more complicated than it seems: the presumption of innocence. Senate Majority Leader Presumed Innocent McConnell has defended Kavanaugh on the principle that he is innocent until proven guilty, while Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has made the point that the hearings are not a lawsuit and thus the legal presumed innocence rule is basically irrelevant. The two senators, despite working within the same system, are able to find very different guidance from the same concept. He found that the ancient Babylonian Code of Hammurabi put the burden of proof on the accuser; that the ancient Presumed Innocent statesman Demosthenes wrote about the importance of not calling people criminals before they were convicted; that a key third-century Roman legal document set forward rules about the evidence an accuser must supply; and that a Medieval European legal principle specified that conviction, Presumed Innocent accusation, defined a criminal. -

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

„Sie Sind Hinter Mir Her“

Kultur „Sie sind hinterLEGENDEN mir her“ Auf 15000 Leinwänden in der ganzen Welt läuft ab dieser Woche ein Dokumentarfilm über die letzten Tage von Michael Jackson. Er entstand während der Proben für sein Comeback – und feiert einen Künstler, der längst ein Wrack war. as Büro von Dieter Wiesner ist ein Memorabilia mit dem Schriftzug „King 45. Geburtstag von Jackson. An den Wän- schwarz möbliertes Hinterzimmer of Pop“. Alle wollen noch einmal groß den hängen Poster, „Dieter“ steht handge- Din einem Gewerbegebiet in Rodgau, an Jackson verdienen. „Seit der Maikl tot schrieben auf einem dieser Plakate, „Stop Erdgeschoss, Gebäude 2F. Auf dem Boden ist“, sagt Wiesner, „ist der größte Kosten- the tabloids“; auf einem anderen „You’re liegt eine Kiste mit Michael-Jackson-Hand- faktor weg.“ the best! Michael“. Stopp die Boulevard- taschen und Michael-Jackson-Stöckelschu- In einer Glasvitrine steht eine Michael- blätter. Du bist der Beste! Michael. hen, Kunstleder made in Germany, gelie- Jackson-Porzellanstatue, angefertigt in Auf einem Foto in einem Regal ist fert aus der Türkei, die jüngste Ladung Rumänien, ein Geschenk Wiesners zum Jackson zu sehen, wie er 2002 an einem 160 der spiegel 44/2009 Sänger Jackson auf seiner Neverland-Ranch 1991 DILIP MEHTA / AGENTUR FOCUS Fenster des Hotel Adlon in Berlin der Men- Er war jahrelang Jacksons Geschäfts- Michael Jackson, der starb, am 25. Juni ge seinen Sohn zeigte. Jeder kennt diesen partner, später sein Manager und Bera- dieses Jahres. Moment des Wahnsinns, weil ihm damals ter. Und Wiesners Büro sieht aus, als Von diesem Michael Jackson erfährt fast das Baby aus den Händen rutschte, hätte sich bis heute daran nichts geän- man, wenn Wiesner den Safe, der unter aber das Bild ist nicht wie die anderen von dert. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

The Cinematic Worlds of Michael Jackson

MA 330.004 / MA430.005 /AMST 341.002 Fall 2016 Revised: 10-7-16 The Cinematic Worlds of Michael Jackson Course Description: From his early years as a child star on the Chitlin’ Circuit and at Motown Records, through the concert rehearsal documentary This is It (released shortly after his death in 2009), Michael Jackson left a rich legacy of recorded music, televised performances, and short films (a description he preferred to “music video”). In this course we’ll look at Jackson’s artistic work as key to his vast influence on popular culture over the past 50 years. While we will emphasize the short films he starred in (of which Thriller is perhaps the most famous), we will also listen to his music, view his concert footage and TV appearances (including some rare interviews) and explore the few feature films in which he appeared as an actor/singer/dancer (The Wiz, Moonwalker). We’ll read from a growing body of scholarly writing on Jackson’s cultural significance, noting the ways he drew from a very diverse performance and musical traditions—including minstrelsy, the work of dance/choreography pioneers like Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, and soul/funk legends like James Brown and Jackie Wilson—to craft a style uniquely his own. Crucially, we will ask how Jackson’s shifting public persona destabilize categories of gender, sexuality, and race----in a manner that was very different from his contemporaries: notably, the recently-deceased David Bowie and Prince. Elevated to superstardom and then made an object of the voracious cultural appetite for scandal, Michael Jackson is now increasingly regarded as a singularly influential figure in the history of popular music and culture. -

Apocalypse Now Redux — Remonter Les Ténèbres Un Maestro Et Son Ultime Chef-D’Oeuvre Apocalypse Now Redux, États-Unis 2001, 197 Minutes Charles-Stéphane Roy

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 15:13 Séquences La revue de cinéma Apocalypse Now Redux — Remonter les ténèbres Un maestro et son ultime chef-d’oeuvre Apocalypse Now Redux, États-Unis 2001, 197 minutes Charles-Stéphane Roy Le cinéma québécois des années 90 Numéro 215, septembre–octobre 2001 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/59182ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (imprimé) 1923-5100 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Roy, C.-S. (2001). Compte rendu de [Apocalypse Now Redux — Remonter les ténèbres : un maestro et son ultime chef-d’oeuvre / Apocalypse Now Redux, États-Unis 2001, 197 minutes]. Séquences, (215), 49–49. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2000 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ APOCALYPSE NOW REDUX Remonter les ténèbres : un maestro et son ultime chef-d'œuvre annes, printemps 1979. Au cœur de l'ancien Palais du CFestival, Francis Ford Coppola se dirige nerveusement vers un microphone et s'adresse à un auditoire impatient. Dans un élan théâtral, il envoie une première missive : « My film is not about Vietnam. -

Michael Jackson's Gesamtkunstwerk

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 5 (November 2015) Michael Jackson’s Gesamtkunstwerk: Artistic Interrelation, Immersion, and Interactivity From the Studio to the Stadium Sylvia J. Martin Michael Jackson produced art in its most total sense. Throughout his forty-year career Jackson merged art forms, melded genres and styles, and promoted an ethos of unity in his work. Jackson’s mastery of combined song and dance is generally acknowledged as the hallmark of his performance. Scholars have not- ed Jackson’s place in the lengthy soul tradition of enmeshed movement and mu- sic (Mercer 39; Neal 2012) with musicologist Jacqueline Warwick describing Jackson as “embodied musicality” (Warwick 249). Jackson’s colleagues have also attested that even when off-stage and off-camera, singing and dancing were frequently inseparable for Jackson. James Ingram, co-songwriter of the Thriller album hit “PYT,” was astonished when he observed Jackson burst into dance moves while recording that song, since in Ingram’s studio experience singers typically conserve their breath for recording (Smiley). Similarly, Bruce Swedien, Jackson’s longtime studio recording engineer, told National Public Radio, “Re- cording [with Jackson] was never a static event. We used to record with the lights out in the studio, and I had him on my drum platform. Michael would dance on that as he did the vocals” (Swedien ix-x). Surveying his life-long body of work, Jackson’s creative capacities, in fact, encompassed acting, directing, producing, staging, and design as well as lyri- cism, music composition, dance, and choreography—and many of these across genres (Brackett 2012). -

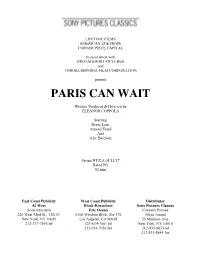

Paris Can Wait

LIFETIME FILMS AMERICAN ZOETROPE CORNER PIECE CAPITAL In association with PROTAGONIST PICTURES and TOHOKUSHINSHA FILM CORPORATION present PARIS CAN WAIT Written, Produced & Directed by ELEANOR COPPOLA Starring Diane Lane Arnaud Viard And Alec Baldwin Opens NY/LA 05/12/17 Rated PG 92 min East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor 42 West Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Scott Feinstein Eric Osuna Carmelo Pirrone 220 West 42nd St., 12th Fl. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Ste 170 Maya Anand New York, NY 10036 Los Angeles, CA 90048 25 Madison Ave. 212-277-7555 tel 323-634-7001 tel New York, NY 10010 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8833 tel 212-833-8844 fax CAST Anne Lockwood Diane LANE Jacques Clement Arnaud VIARD Michael Lockwood Alec BALDWIN Martine Elise TIELROOY Carole Elodie NAVARRE Mechanic Serge ONTENIENTE Philippe Pierre CUQ Musée Des Tissus Guard Cédric MONNET Concierge Aurore CLEMENT Suzanne Davia NELSON Alexandra Eleanor LAMBERT FILMMAKERS Written, Produced and Directed by ELEANOR COPPOLA Produced by FRED ROOS Executive Producers MICHAEL ZAKIN LISA HAMILTON DALY TANYA LOPEZ ROB SHARENOW MOLLY THOMPSON Director of Photography Crystel Fournier, Afc Production Designer ANNE SEIBEL, ADC Costume Designer MILENA CANONERO Editor GLEN SCANTLEBURY Sound Designer RICHARD BEGGS Music by LAURA KARPMAN Synopses LOG LINE A devoted American wife (Diane Lane) with a workaholic inattentive husband (Alec Baldwin) takes an unexpected journey from Cannes to Paris with a charming Frenchman (Arnaud Viard) that reawakens her sense of self and joie de vivre. LONG SYNOPSIS Eleanor Coppola’s feature film directorial and screenwriting debut at the age of 81 stars Academy Award® nominee Diane Lane as a Hollywood producer’s wife who unexpectedly takes a trip through France, which reawakens her sense of self and her joie de vivre.