Joe Montana FOOTBALL SUPERSTARS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gether, Regardless Also Note That Rule Changes and Equipment Improve- of Type, Rather Than Having Three Or Four Separate AHP Ments Can Impact Records

Journal of Sports Analytics 2 (2016) 1–18 1 DOI 10.3233/JSA-150007 IOS Press Revisiting the ranking of outstanding professional sports records Matthew J. Liberatorea, Bret R. Myersa,∗, Robert L. Nydicka and Howard J. Weissb aVillanova University, Villanova, PA, USA bTemple University Abstract. Twenty-eight years ago Golden and Wasil (1987) presented the use of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for ranking outstanding sports records. Since then much has changed with respect to sports and sports records, the application and theory of the AHP, and the availability of the internet for accessing data. In this paper we revisit the ranking of outstanding sports records and build on past work, focusing on a comprehensive set of records from the four major American professional sports. We interviewed and corresponded with two sports experts and applied an AHP-based approach that features both the traditional pairwise comparison and the AHP rating method to elicit the necessary judgments from these experts. The most outstanding sports records are presented, discussed and compared to Golden and Wasil’s results from a quarter century earlier. Keywords: Sports, analytics, Analytic Hierarchy Process, evaluation and ranking, expert opinion 1. Introduction considered, create a single AHP analysis for differ- ent types of records (career, season, consecutive and In 1987, Golden and Wasil (GW) applied the Ana- game), and harness the opinions of sports experts to lytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to rank what they adjust the set of criteria and their weights and to drive considered to be “some of the greatest active sports the evaluation process. records” (Golden and Wasil, 1987). -

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O. Box 535000 Indianapolis, IN 46253 www.colts.com REGULAR SEASON WEEK 6 INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-2) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-0) 8:30 P.M. EDT | SUNDAY, OCT. 18, 2015 | LUCAS OIL STADIUM COLTS HOST DEFENDING SUPER BOWL BROADCAST INFORMATION CHAMPION NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS TV coverage: NBC The Indianapolis Colts will host the New England Play-by-Play: Al Michaels Patriots on Sunday Night Football on NBC. Color Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Game time is set for 8:30 p.m. at Lucas Oil Sta- dium. Sideline: Michele Tafoya Radio coverage: WFNI & WLHK The matchup will mark the 75th all-time meeting between the teams in the regular season, with Play-by-Play: Bob Lamey the Patriots holding a 46-28 advantage. Color Analyst: Jim Sorgi Sideline: Matt Taylor Last week, the Colts defeated the Texans, 27- 20, on Thursday Night Football in Houston. The Radio coverage: Westwood One Sports victory gave the Colts their 16th consecutive win Colts Wide Receiver within the AFC South Division, which set a new Play-by-Play: Kevin Kugler Andre Johnson NFL record and is currently the longest active Color Analyst: James Lofton streak in the league. Quarterback Matt Hasselbeck started for the second consecutive INDIANAPOLIS COLTS 2015 SCHEDULE week and completed 18-of-29 passes for 213 yards and two touch- downs. Indianapolis got off to a quick 13-0 lead after kicker Adam PRESEASON (1-3) Vinatieri connected on two field goals and wide receiver Andre John- Day Date Opponent TV Time/Result son caught a touchdown. -

2016 MIZZOU FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE Paul Adams Offensive Lineman RS So

FOOTBALL 2016 MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016 TEAM INFORMATION.......................................................................................................... 1-10 Mizzou At-A-Glance 2-3 Mizzou Rosters 4-7 About the Tigers/Facts and Figures 8-9 Schedule/Media Information 10 2016 MIZZOU TIGERS ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 11-90 MIZZOU COACHES AND STAFF .............................................................................................. 91-118 Head Coach Barry Odom 92-94 Assistant Coaches/Support Staff 95-117 Missouri Administration 118 2015 SEASON REVIEW ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 119-132 Season Results/Team Season Stats 120-121 Individual Season Statistics 122-126 Game-by-Game Starting Lineups 127 Game-by-Game Team Statistics 128-130 SEC Standings 131 MISSOURI RECORD BOOK .................................................................................................... 133-174 THE MIZZOU 2016 FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE was written, edited and designed by Associate AD/Strategic Communications Chad Moller and Assistant Director of Strategic Communications Shawn Davis Covers designed by Ali Fisher Photos provided by Mike Krebs, Tim Nwachuku, Tim Tai, L G Patterson and the Strategic Communications Archives Publishing provided by Walsworth with special assistance from Senior Customer Service Representative Jenny Shoemaker MIZZOU AT-A-GLANCE 2015 SCHEDULE/RESULTS -

State News 19781006A.Pdf

2 Michigon State News, East Lansing, Michigan MSU v. ND: two hungry teams Both teams need wins after rather slow start By JOECENTERS State News Sports Writer When MSU hosts Notre Dame Saturday in a 1:30 p.m. clash at Spartan Stadium, it will be the 44th time that the two football teams will have met. But this game will be far different than most of the meetings between the two schools. This contest will be between two tearhs that are fighting for its lives, which is unusual for both MSU and Notre Dame this early in the season. Both schools are 1-2 this season and the team that winds up on the short end of the score could find itself in a hole with no way to get out. The Irish lost their first two games of the season, a 3-0 setback to Missouri and a 28-14 defeat at the hands of Michigan, MSU's opponent next week in Ann Arbor. Last Saturday, Notre Dame finally got on the right track by beating Purdue 10-6. State News/Deborah J. Borin The Boilermakers took a 6-0 halftime lead on two field goals by Scott Sovereen, but that's all of the offense that Purdue could Lonnie Middleton (44), MSU's starting fullback, tries to burst past three muster against the Irish. A third quarter touchdown by Jerome Syracuse defenders in MSU's 49-21 win earlier this season. Heavens and a 27-yard field goal by Joe Unis later on in the same Middleton and his teammates will be seeking to rebound against Notre stanza gave Notre Dame its margin of victory. -

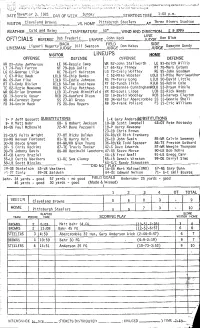

OFIICIALS Referelbob Frederic UMPIRE JUDGE BACK FIELD SIDE Ligourii4agert Swanson Don Hakes Duwaynegandy LINESMAN JIJDGE__

____ _____ _____ ______JUDGE___________ ' 'tSbi.Th,14i' 1(orn Al• (ireirt r, sm—un .J;'u Lv,e "Se s On ci Sunday 1:00 p.m. DAY OF WEEK TIME, Rivers Stadium VISITOR Cleveland Browns VS. HOMEPittsburgh Steelers AT__Three 500 WEATHER Cold and Rainy TEMPERATURE WIND AND DIRECTION. E @ 8MPH LI NE John Keck Ron Blum OFIICIALS REFERELBob Frederic UMPIRE JUDGE BACK FIELD SIDE LigouriI4agert Swanson Don Hakes DuwayneGandy LINESMAN JIJDGE__.. UN EU PS HOME OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE WR89—John Jefferson LE96—ReggieCamp WR82-John Stallworth LE93-Keith Willis LT74-Paul Farren NT79—Bob Golic LT65-Ray Pinney NT78—Mark Catano LG62-George Lilja RE78—Carl Hairston LG73-Craig Woifley RE95—John Goodman C61-Mike Baab LOLB56—Chip Banks C52-Mike Webster LOLB57-Mike Merriweather RG69—Dan Fike LJLB51—Eddie Johnson RG 74-Terry Long LILB50—David Little RT63—Cody Risien RILB50—Tom Cousineau PT62-Tunch 11km RILB56-RobinCole TE82-Ozzie Newsonie ROLB57—Clay Matthews TE89-Bennie CunninghamR0LB53-BryanHinkle t'JR86-Brian Brennan LCB31—Frank Hinnifield WR83-Louis Lipps LCB22-Rick Woods QB19—Bernie Kosar RC B29-Hanford Dixon QB19-David Woodley RCB33-Harvey Clayton RB44-Earnest Byner $527—Al Gross RB34-Walter Abercrombie SS31-Donnie Shell FB34-Kevin Mack ES20-Don Rogers RB3D-Frank Pollard FS21—Eric Williams 7— P Jeff GossettSUBSTITUTIONS 1-K Gary Anders&JJBSTITUTIONS 9- K Matt Bahr 68— G Robert Jackson 10-QB Scott Campbell 63-UT Pete Rostosky 16-05Paul McDonald 72-NT Dave Puzzuoli 16-P Harry Newsome 23—GB Chris Brown 22-GB/S FelixWright 77-01 Ricky Bolden 24-RB/KR -

Dwight Clark, 61, Dies; Made a Touchdown Catch for the Ages

Dwight Clark, 61, Dies; Made a Touchdown Catch for the Ages https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/05/obituaries/dwight-clark-61-dies-m... Dwight Clark, 61, Dies; Made a Touchdown Catch for the Ages Dwight Clark making what came to be called simply “The Catch” to tie the score with less than a minute to go in the 1982 N.F.C. championship game in San Francisco. The 49ers beat the Dallas Cowboys, 28-27.CreditPhil Huber/The Dallas Morning News, via Associated Press Dwight Clark, the wide receiver whose spectacular last-minute leaping touchdown reception, known as “The Catch,” propelled the San Francisco 49ers toward the first N.F.L. championship in their history and ushered in their dominance of the league through the 1980s, died on Monday in Whitefish, Mont. He was 61. His death was announced by his wife, Kelly, on his Twitter account. He revealed in March 2017 that he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the degenerative nerve-cell disorder known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Clark was only a 10th-round pick by the 49ers in the 1979 N.F.L. draft, having caught just three touchdown passes playing for Clemson. But, teaming up with the future Hall of Fame quarterback Joe Montana, he became a leading pro receiver. With 58 seconds remaining in the January 1982 National Football Conference championship game between the underdog 49ers and the Dallas Cowboys on a soggy Candlestick Park field, San Francisco had the football on the Dallas 6-yard line, trailing by 6 points. It was third down with 3 yards to go. -

Classified 643^2711 Violence Mar State's Holida

20 - THE HERALD, Sat., Jan. 2. 1982 HDVERTISING MniERnSING MTES It wds a handyman's special... page 13 Classified 643^2711 Minimum Charge 22_pondomlniurrt8 15 W ords V EMPLOYMENT 23— Homes for Sale 35— Heaimg-Ptumbing 46— Sporting Goods 58— Mtsc for Rent 12:00 nooo the day 24— Lols-Land for Sale 36— Flooring 47— Garden Products 59^Home8/Apt$< to Sti8|ro 48— Antiques and ^ound f^lnveslment Property 37— Moving-TrucKing-Storage PER WORD PER DAY before publication. 13— Help Wanted 49— Wanted to Buy AUTOMOTIVE 2— Par sonata 26— Business Property 38— Services Wanted 14— Business Opportunities 50~ P ro du ce Deadline for Saturday Is 3 - - Announcements 15— Situatiorf Wanted 27— Relort Property 1 D A Y ................. 14« 4'-Chrlstma8 Trees 28— Real Estate Wanted MISC. FOR SALE RENTALS_______ 8l-.Autos for Sale 12 noon Friday; Mon 5— Auctions 62— Trucks for Sale 3 D A YS .........13iF EDUCATION 63— Heavy Equipment for Sale day's deadline Is 2:30 MI8C. SERVICES 40— Household Goods 52— Rooms for Rent 53— Apartments for Rent 64— Motorcycits-Bicycles 6 P A Y S ........ 12(T Clearing, windy FINANCIAL 18— Private Instructions 41— Articles for Seie 65— Campers-Trailert'Mobile Manchester, Connj Friday. 31— Services Offered 42— Building Supplies 54— Homes for Rent 19— SchoolS'Ciasses Homes 26 D A Y S ........... 1 U 6— Mortgage Loans 20— Instructions Wanted 32— Painting-Papering 43— PetS'Birds-D^s 55— OtriceS'Stores for Rent tonight, Tuesday Phone 643-2711 33— Buildirrg-Contracting 56— Resort Property for Rent 66— Automotive Service HAPPV AOS $3.00 PER INCH Mon.,. -

The Magnificent Seven

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 26, No. 4 (2004) THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN by Coach TJ Troup The day after Christmas in 1954 the Cleveland Browns hosted the Detroit Lions for the NFL title. It was the third consecutive year these two teams would decide the championship. The Browns had lost three consecutive championship games, including the last two to the Lions. Browns QB Otto Graham had not played particulary well in those three losses, and since he was the “trigger” man in the Cleveland offense, and a man of intense pride, this was the “crossroads” game of his career. Graham responded to the challenge by contributing five touchdowns in a 56 to 10 victory. Otto completed 9 of 12 passes for 163 yards and 2 touchdowns, and scored 3 himself on short runs from scrimmage. Though he announced his retirement, Otto eventually returned for one final season in 1955. Graham again led the Browns to the title, this time defeating the Rams in the Los Angeles Coliseum 38 to 14. When assessing a quarterback’s career how much emphasis should be placed on his passing statistics? Long after Otto Graham retired, the NFL began to use the passer rating system to evaluate the passing efficiency of each individual quarterback. Using that system how efficient was Graham, and where does he rank in comparison with other champion quarterbacks? The passer rating system is divided into four equal categories; completion percentage per pass attempt, yards gained per pass attempt, touchdown percentage per pass attempt, and interception percentage per pass attempt. Is there a simpler way of stating this? We want our team to complete as many long passes for as many touchdowns as possible in as few attempts as possible, without throwing an interception. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Newton Wrestling

NEWTON WRESTLING 10 REASONS WHY FOOTBALL PLAYERS SHOULD WRESTLE 1. Agility--The ability of one to change the position of his body efficiently and easily. 2. Quickness--The ability to make a series of movements in a very short period of time. 3. Balance--The maintenance of body equilibrium through muscular control. 4. Flexibility--The ability to make a wide range of muscular movements. 5. Coordination--The ability to put together a combination of movements in a flowing rhythm. 6. Endurance--The development of muscular and cardiovascular-respiratory stamina. 7. Muscular Power (explosiveness)--The ability to use strength and speed simultaneously. 8. Aggressiveness--The willingness to keep on trying or pushing your adversary at all times. 9. Discipline--The desire to make the sacrifices necessary to become a better athlete and person. 10. A Winning Attitude--The inner knowledge that you will do your best - win or lose. NFL FOOTBALL PLAYERS WHO HAVE WRESTLED "I would have all my offensive linemen wrestle if I could." -John Madden - Hall of Fame NFL Coach I'm a huge wrestling fan. Wrestlers have so many great qualities that athletes need to have." - Bob Stoops - Oklahoma Sooners Head Football Coach Ray Lewis*, Baltimore Ravens – 2x FL State Champ - Bo Jackson*, RB, Oakland Raiders - Tedy Bruschi*, ILB, New England Patriots - Willie Roaf*, OT, New Orleans Saints - Warren Sapp*, DT Tampa Bay Buccaneers – FL State Champ Roger Craig*, RB, San Francisco 49’ers - Larry Czonka**, RB, Miami Dolphins - Tony Siragusa*, DT, Baltimore Ravens NJ State Champ - Ricky Williams*, RB, Miami Dolphins -Dahanie Jones, LB, New York Giants - Ronnie Lott**, DB, San Francisco 49’ers - Jim Nance, FB, New England Patriots NCAA Champ - Dan Dierdorff**, OT, St. -

Seminoles in the Nfl Draft

137 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME All-time Florida State gridiron greats Walter Jones and Derrick Brooks are used to making history. The longtime NFL stars added an achievement that will without a doubt move to the top of their accolade-filled biographies when they were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame inAugust, 2014. Jones and Brooks became the first pair of first-ballot Hall of Famers from the same class who attended the same college in over 40 years. The pair’s journey together started 20 years ago. Just as Brooks was wrapping up his All-America career at Florida State in 1994, Jones was joining the Seminoles out of Holmes Community College (Miss.) for the 1995 season. DERRICK BROOKS Linebacker 1991-94 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame WALTER JONES Offensive Tackle 1995-96 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame 138 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME They never played on the same team at Florida State, but Jones distinctly remembers how excited he was to follow in the footsteps of the star linebacker whom he called the face of the Seminoles’ program. Jones and Brooks were the best at what they did for over a decade in the NFL. Brooks went to 11 Pro Bowls and never missed a game in 14 seasons (all with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers), while Jones became the NFL’s premier left tackle, going to nine Pro Bowls over 12 seasons with the Seattle Seahawks. Both retired in 2008, and, six years later, Jones and Brooks were teammates for the first time as first-ballot Hall of Famers.