College-Completion-Toolkit.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

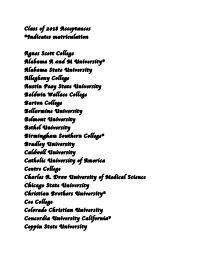

Class of 2018 Acceptances *Indicates Matriculation Agnes Scott

Class of 2018 Acceptances *Indicates matriculation Agnes Scott College Alabama A and M University* Alabama State University Allegheny College Austin Peay State University Baldwin Wallace College Barton College Bellarmine University Belmont University Bethel University Birmingham Southern College* Bradley University Caldwell University Catholic University of America Centre College Charles R. Drew University of Medical Science Chicago State University Christian Brothers University* Coe College Colorado Christian University Concordia University California* Coppin State University DePaul University Dillard University Eckerd College Fordham University Franklin and Marshall College Georgia State University Gordon College Hendrix College Hollins University Jackson State University Johnson C. Smith University Keiser University Langston University* Loyola College Loyola University- Chicago Loyola University- New Orleans Mary Baldwin University Middle Tennessee State University Millsaps College Mississippi State University* Mount Holyoke College Mount Saint Mary’s College Nova Southeastern University Ohio Wesleyan Oglethorpe University Philander Smith College Pratt Institute Ringling College or Art and Design Rollins College Rust College Salem College Savannah College or Art and Design Southeast Missouri State University Southwest Tennessee Community College* Spellman College Spring Hill College St. Louis University Stonehill College Talladega College Tennessee State University Texas Christian University Tuskegee University* University of Alabama at Birmingham University of Dayton University of Houston University of Kentucky University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa University of Memphis* University of Mississippi University of North Alabama University of Florida University of Southern Mississippi University of Tampa University of Tennessee Chattanooga* University of Tennessee Knoxville* University of Tennessee Marin Virginia State University Voorhees College Wake Forest University* Wiley College Xavier University, Louisiana Xavier University, Ohio . -

2010-2011 Education Graduate Catalog

The Salem College Graduate Catalog includes the official announcements of academic programs and policies. Graduate students are responsible for knowledge of information contained therein. Although the listing of courses in this catalog is meant to indicate the content and scope of the curriculum, changes may be necessary and the actual offerings in any term may differ from prior announcements. Programs and policies are subject to change from time to time in accordance with the procedures established by the faculty and administration of the College. Salem College welcomes qualified students regardless of race, color, national origin, sexual orientation, religion or disability to all the rights, privileges, programs and activities of this institution. Salem College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) to award baccalaureate and master’s degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call (404) 679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Salem College. The Department of Teacher Education and Graduate Studies at Salem College is accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE), www.ncate.org. This accreditation covers initial teacher preparation programs and advanced educator preparation programs at Salem College. All specialty area programs for teacher licensure have been approved by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI). The Salem College School of Music is an accredited institutional member of the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM). Salem College is an equal-opportunity educational institution as defined by Title VI of The Civil Rights Act of 1964. -

2002-2003 Undergraduate Catalog Supplement

SALEM Salem College • 2002 Supplement to the 2001-2003 Academic Catalog To the users of the 2001-2003 Salem College Academic Catalog: This supplement is intended to give you the most up-to-date information regarding the academic programs at Salem College for the fall and and spring semesters of 2002 and 2003, respectively. Please refer to this supplement to the 2001-2003 Academic Catolog for the following specific information: • 2002-2003 Financial Information on pages 3S-5S replaces pages 21-22 of the catalog. • 2002 Board of Trustees, Board of Visitors, Faculty, Administration and Staff on pages 31S-48S replaces pages 204-220. See individual department headings in this supplement for complete 2002 updates for each department/major including faculty; major requirements; course additions, deletions, and changes. The page number listed with the new information refers to the catalog pages on which the original information appears. 2002 ACADEMIC CATALOG SUPPLEMENT • 2S Salem College • page 12. Academic Computing Facilities, Change: First paragraph, last sentances...should read...A videoconference center in the Fine Arts Center serves as a multimedia and laptop classroom as well as a videoconference facility. The library has laptop computers available for checking the online catalog and other online resources. • page 12. Athletic Facilities, Change: First paragraph, first sentance...should read...Salem offers a variety of physical education activities and nine intercollegiate sports. • page 12. Library Services, Change: First paragraph, last sentance...should read...These useful resources are accessible to Salem students from any internet workstation. • page 12. Library Services, Change: Second paragraph, fifth sentance...should read...The Lorraine F. -

Women's Higher Education in the 21St Century

Women’s College Coalition Annual Conference | September 21-22 WOMEN CREATING CHANGE Education, Leadership & Philanthropy WOMEN CREATING CHANGE: Education, Leadership, Philanthropy THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS WOMEN CREATING CHANGE: Education, Leadership, Philanthropy THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS WOMEN CREATING CHANGE: Education, Leadership, Philanthropy THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS WOMEN CREATING CHANGE: Education, Leadership, Philanthropy 7:30am Registration and Continental Breakfast 9:00am Welcome & Introductions by Presidents from Host Colleges Presidents’ Panel: Women Creating Change – Today’s Civic Engagement and Women’s Colleges 10:30am Student Voices on Civic Engagement 11:00am Roundtable Discussions 12:00pm Networking Lunch: Connect with colleagues 1:00pm Chief Academic Officers Panel: New Ways of Learning How can we create signature programs to distinguish ourselves in this competitive environment? 1:45pm Roundtable Discussions 2:30pm Women Creating Change: Leadership and Social Innovation 3:00pm Leadership Panel: How do we work together to connect the multi-sector women’s leadership efforts to accelerate women’s progress? 3:45pm Roundtable Discussions 6:00pm Reception, Dinner and Program at Spelman College (Transportation provided) AGENDA –THURSDAY 9/21 WOMEN CREATING CHANGE: Education, Leadership, Philanthropy Support Our Communications Efforts ✓ Visit our website regularly: womenscolleges.org ✓ Check your information on the website for accuracy ✓ Make sure we have your e-mail address ✓ Like/Follow us on Facebook: @womenscollegecoalition ✓ Follow -

Class of 2016 College Acceptance List Appalachian State University

Class of 2016 College Acceptance List Appalachian State University (1) Howard University (1) The University of North Carolina at Auburn University - 1 (7) Indiana University at Bloomington (1) Chapel Hill (1) Bradley University (1) Lehigh University (1) University of California, Davis - 1 (2) Brown University - 1 (1) Limestone College (2) University of California, Irvine (1) Bryn Mawr College - 1 (1) Louisiana State University (1) University of California, Santa Cruz (1) Carleton College - 1 (1) Methodist University (1) University of Florida (1) Chapman University (1) Middlebury College (2) University of Mississippi (2) Charleston Southern University (1) Midlands Technical College - 1 (1) University of Missouri Kansas City (1) Claflin University - 1 (2) Mississippi State University - 1 (1) University of North Carolina Clemson University - 6 (16) Morehouse College (2) at Asheville (1) Coastal Carolina University - 1 (6) Newberry College (1) University of Notre Dame - 1 (1) College of Charleston - 3 (14) North Carolina State University (1) University of Richmond (2) Davidson College (1) Northeastern University (1) University of South Alabama (1) Drew University (1) Presbyterian College - 1 (4) University of South Carolina - 10 (25) Duke University - 1 (1) Purdue University (1) University of Southern California (1) East Tennessee State University (2) Queens University of Charlotte (1) University of St Andrews (1) Eckerd College (1) Rhodes College (2) University of Tennessee, Knoxville (2) Elon University (2) Rutgers University-New Brunswick -

List of Women's Colleges and Universities

LIST OF WOMEN’S COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES Agnes Scott College 141 E. College Avenue Decatur, GA 30030 Alverno College P.O. Box 343922 Milwaukee, WI 53215-4020 Barnard College 3009 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Bay Path College 588 Longmeadow Street Longmeadow, MA 01106 Bennett College 900 E. Washington Street Greensboro, NC 27401 Brenau University 204 Boulevard Gainesville, GA 30501 Bryn Mawr College 101 North Merion Avenue Bryn Mawr, PA 19010 Carlow College 3333 Fifth Avenue Pittsburg, PA 15213 Cedar Crest College 100 College Drive Allentown, PA 18104 Chatham College Woodlawn Road Pittsburg, PA 19118 College of New Rochelle 29 Castle Place New Rochelle, NY 10805 College of Notre Dame MD 4701 North Charles Street Baltimore, MD 21210 College of Saint Benedict 37 S. College Avenue St. Joseph, MN 56374 College of Saint Catherine 2004 Randolph Avenue St. Paul, MN 55105 College of St. Elizabeth 2 Convent Road Morristown, NJ 07960-6989 College of Saint Mary 1901 South 72nd Street Omaha, NE 68124 Columbia College 1301 Columbia College Dr. Columbia, SC 29203 Converse College 580 East Main Street Spartanburg, SC 29301 Douglass College Rutgers University New Burnswick, NJ 08903 Georgian Court College 900 Lakewood Avenue Lakewood, NJ 08701-2697 Hollins University P.O. Box 9707 Roanoke, VA 24020-1707 Judson College P.O. Box 120 Marion, AL 36756 Mary Baldwin College Stauton, VA 24401 Midway College 512 E. Stephens Street Midway, KY 40347 Meredith College 3800 Hillsborough Street Raleigh, NC 26707-5298 Mills College 5000 MacArthur Blvd. Oakland, CA 94613 Mississippi Univ. for Women Box W-1609 Columbus, MS 39701 Moore College of Art 20th and The Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19103 Mount Holyoke College 50 College Street South Hadley, MA 01075-1453 Mount Mary College 2900 N Menomonee River Pkwy Milwaukee, WI 53222 Mount St. -

Why a Women's College?

Why a Women’s College? Brought to you by Collegewise counselors (and proud women’s college graduates): Sara Kratzok and Casey Near Why a Women’s College by Sara Kratzok and Casey Near is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The copyright of this work belongs to the authors, who are solely responsible for the content. WHAT YOU CAN DO You are given the unlimited right to print this guide and to distribute it electronically (via email, your website, or any other means). You can print out pages and put them in your office for your students. You can include it in a parent newsletter home to your school community, hand it out to the PTA members, and generally share it with anyone who is interested. But you may not alter this guide in any way, and you may not charge for it. Second Edition February 2014 Page 2 How to use this guide This one goes out to the ladies We wrote this guide for all young women interested in pursuing higher education. Full stop. Yes, researchers tell us that less than 5% of high school-aged women will even consider applying to women’s colleges, but we wrote this for all young women who are thoughtfully analyzing ALL of their college options. We also wrote this guide to help arm high school guidance counselors, independent college counselors, and community-based college advisors with valid, interesting, and perhaps even funny information about women’s colleges they can share with their students. So, if you’re a high school student reading this guide, our goal is to provide you with an alternative viewpoint on your college search, one that you may not have previously thought about. -

2011-2012 Undergraduate Catalog

Salem College Undergraduate Catalog 2011-2012 The Salem College Undergraduate Catalog includes the official announcements of academic programs and policies. Undergraduate students are responsible for knowledge of information contained therein. Although the listing of courses in this catalog is meant to indicate the content and scope of the curriculum, changes may be necessary and the actual offerings in any term may differ from prior announcements. Programs and policies are subject to change from time to time in accordance with the procedures established by the faculty and administration of the College. Salem College welcomes qualified students regardless of race, color, national origin, sexual orientation, religion or disability to all the rights, privileges, programs and activities of this institution. Salem College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) to award baccalaureate and master’s degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call (404) 679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Salem College. The Department of Teacher Education and Graduate Studies at Salem College is accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE), www.ncate.org. This accreditation covers initial teacher preparation programs and advanced educator preparation programs at Salem College. All specialty area programs for teacher licensure have been approved by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI). The Salem College School of Music is an accredited institutional member of the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM). Salem College is an equal-opportunity educational institution as defined by Title VI of The Civil Rights Act of 1964. -

2019 Guilford College Invitational

GCY Swim Team - Bryan HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 8:56 PM 10/5/2019 Page 1 2019 Guilford College Invitational - 10/5/2019 Team Rankings - Through Event 208 Women - Team Scores Place School Points 1 UNC Pembroke UNC Pembroke 572 2 Guilford College Guilford College 266 3 Hollins University Hollins University 262 4 William Peace University William Peace University 155 5 Sweet Briar College Sweet Briar College 151 6 Ferrum College Ferrum College 132 7 Salem College Spirits Salem College Spirits 55 Total 1,593.00 Men - Team Scores Place School Points 1 Greensboro College Greensboro College 362 2 William Peace University William Peace University 355 3 Ferrum College Ferrum College 338 Total 1,055.00 GCY Swim Team - Bryan HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 8:54 PM 10/5/2019 Page 1 2019 Guilford College Invitational - 10/5/2019 Results Event 101 Women 200 Yard Freestyle Relay Team Relay Seed Time Finals Time Points 1 UNC Pembroke-NC A NT 1:44.87 40 1) Rodriguez Matos, Ketlyn 2) Bateman, Bianca 3) Knight, Jaycie 4) Morden, Sarah 2 Hollins University A 1:52.88 1:51.90 34 1) DeVarona, Hanna 20 2) Sanchez, Alexandra 21 3) Bull, Megan 19 4) Miehlke, Emily 20 3 Guilford College-NC A 1:55.70 1:55.71 32 1) Cessna, Megan R 18 2) Hunt, Molly M 18 3) Shenhouse, Rebecca R 19 4) O'Halloran, Carolyn A 21 4 UNC Pembroke-NC B NT 1:56.37 30 1) Ramosbarbosa, Karina 2) Brousseau, Victoria 3) Hunter, Megan 4) Hernandez Martinez, Ignayara 5 William Peace University-NC A NT 2:00.10 28 1) Butler, Lindsay 19 2) Dhar, Alisha 18 3) Swain, Ally 18 4) Leischner, Peyton 18 6 Sweet -

Lynn Pasquerella

The Inauguration of Lynn Pasquerella Eighteenth President of Mount Holyoke College .. The Inauguration of Lynn Pasquerella Eighteenth President Friday, the Twenty-fourth of September Two Thousand and Ten Two O’clock in the Afternoon Richard Glenn Gettell Amphitheater Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, Massachusetts One of the benefits of studying at a women’s college was being able to look at issues from the perspective of a community of women. That opportunity shaped my commitment to women’s education. I believe that our commitment to women’s education and leadership must extend beyond the academy into the extramural community to change the lives of women around the world in order to provide the access that we’ve been privileged to receive. — President Lynn Pasquerella · 2 · The President ynn Pasquerella, a celebrated philosopher and medical ethicist, assumed the presidency L of Mount Holyoke College on July 1, 2010. Her appointment marks a homecoming for Pasquerella, who enrolled at Mount Holyoke in 1978 as a transfer student from Quinebaug Valley Community College. While working full-time to support herself, Pasquerella majored in philosophy and graduated magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Mount Holyoke in 1980. A native of Connecticut, Pasquerella was the first in her family to graduate from college. Encouraged by her Mount Holyoke professors to pursue graduate study, she received a full fellowship to Brown University, where she earned a Ph.D. in philosophy. From 1985 to 2008, Pasquerella taught philosophy at the University of Rhode Island. In 2004, she became associate dean of URI’s graduate school and, in 2006, was named vice provost for research and dean of the graduate school. -

Hollins Student Life (1929 Sept 28) Hollins College

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Hollins Student Newspapers Hollins Student Newspapers 9-28-1929 Hollins Student Life (1929 Sept 28) Hollins College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/newspapers Part of the Higher Education Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Hollins College, "Hollins Student Life (1929 Sept 28)" (1929). Hollins Student Newspapers. 12. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/newspapers/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hollins Student Newspapers at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hollins Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. , I ' ( , ... \ 1 l t J L- '-_ [ \ () I.l \ I I I I I I ( ) 1.1.1 :\ S co I. 1, 1''.( ', 1'',. SI -: I)'IT\IBI<R IlOLL! :\S, \ . I RC 1:\ L\ :\ I ' .\1 BE R I ---- Hollins Welcomes You! ... New Faculty Members STUDENT GOVERNMENT Welcomed to Hollins ANNOUNCES THE HONOR II I" 1\1\ J.~.. ~ : ""'f'''''''T~ rOR ",.,,~.,,~ IS FORMI"LL I UI LI' .. ., I The most pronounced of a II the striking ., I UULI1 I ~ t ~[~~fUll changes that have occurred at Hollins ~or the sessioll of 1929-1930 are the changes 111 the Eleanor vVilson, President of the Student Last \'Car we started the custom of announc Facult\·. A number of the departments of Both', formally opened College Student Cove.rn ing the' honor students for the session at the instru~tion ha\'e been greatly broadened by men't for the sessioll 1929-J930, at a meeting first convocation. -

861-1524 Bethlehem, PA 18018 [email protected]

CHARLES RIDDICK WEBER ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF PASTORAL MINISTRY CHAPLAIN MORAVIAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 1200 Main Street (610) 861-1524 Bethlehem, PA 18018 [email protected] Educational Experience: Ph.D., University of Virginia, Department of Religious Studies 8.99—5.09 Dissertation “Zinzendorfs’ Utopia: Discovering the Radical Roots of the Eighteenth Century Brüdergemeine in Wachovia,” addresses the theological formulations found in the liturgies, personal and burial references and the sociological constructs regarding race and gender that formed the foundations of the Moravian congregations in North Carolina from 1753 to 1818 M.Div., Duke Divinity School, 8.96—8.00 Coursework focused on Church History, Historical Theology and Theology Clinical Pastoral Education at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, 6.90—8.90 B.A. UNC-Chapel Hill, 8.83—5.88 Majors in History and Economics with Honors in Economics Academic Honors and Prizes: University of Virginia Presidential Fellowship 1999, 2007-9 Duke Divinity School Exchange Student at the University of Bonn, 1998-1999 UNC-Chapel Hill Dean’s List every semester Richard Levin Band Award for Outstanding Senior Leadership, 1987 ΦΒΚ, 1986 ΦΗΣ (Freshman Honor Society), 1984 Writing Projects in Process: “The Moravian Church in North Carolina” chapter in a forthcoming book religion in North Carolina, published by the North Caroliniana Society, Glenn Jonas, editor “Moravian Worship” chapter in a forthcoming resource book on the history, theology, polity, and practices of the worldwide Moravian Church published through the desk of the Unity Administrator, Craig Atwood and Peter Vogt, editors “Moravian Women in Ministry: Our Views on the Authority of Particular Scriptures Influence How Our Sisters in Christ Can Use their Gifts” chapter in a forthcoming book on Violence Against Women, Moravian Women’s Desk, Deborah Appler and Patty Garner, editors Published Articles Moravian History that isn’t ZZZZZZZzzzzzzzzzz.