Idle Attentions: Modern Fiction and the Dismissal of Distraction By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nostromo a Tale of the Seaboard

NOSTROMO A TALE OF THE SEABOARD By Joseph Conrad "So foul a sky clears not without a storm." —SHAKESPEARE TO JOHN GALSWORTHY Prepared and Published by: Ebd E-BooksDirectory.com AUTHOR'S NOTE "Nostromo" is the most anxiously meditated of the longer novels which belong to the period following upon the publication of the "Typhoon" volume of short stories. I don't mean to say that I became then conscious of any impending change in my mentality and in my attitude towards the tasks of my writing life. And perhaps there was never any change, except in that mysterious, extraneous thing which has nothing to do with the theories of art; a subtle change in the nature of the inspiration; a phenomenon for which I can not in any way be held responsible. What, however, did cause me some concern was that after finishing the last story of the "Typhoon" volume it seemed somehow that there was nothing more in the world to write about. This so strangely negative but disturbing mood lasted some little time; and then, as with many of my longer stories, the first hint for "Nostromo" came to me in the shape of a vagrant anecdote completely destitute of valuable details. As a matter of fact in 1875 or '6, when very young, in the West Indies or rather in the Gulf of Mexico, for my contacts with land were short, few, and fleeting, I heard the story of some man who was supposed to have stolen single-handed a whole lighter-full of silver, somewhere on the Tierra Firme seaboard during the troubles of a revolution. -

Michael Koryta Interviews Dean Koontz MICHAEL: in the New Novel

Michael Koryta Interviews Dean Koontz MICHAEL: In the new novel, ODD APOCALYPSE, you write that "between birth and burial, we find ourselves in a comedy of mysteries." That statement could be a guiding light for the ODD series, and perhaps even your work in general of late. Was allowing the laughs to join the darkness a conscious decision? DEAN: Humor began to enter my work as far back as WATCHERS (1987), and by LIGHTNING (1988), my agent and publisher at that time became alarmed and counseled me that suspense and humor never mix. They were not able to offer a cogent explanation of why the two never mix. One of my favorite films of all time is NORTH BY NORTHWEST, which is tense and funny; so I just kept doing what I was doing. By the time I moved to Bantam Books with FEAR NOTHING (1998), humor became the binding glue in all of my books except for THE TAKING, VELOCITY, THE HUSBAND, and YOUR HEART BELONGS TO ME. Odd Thomas is speaking for me when he says, "Humanity is a parade of fools, and I'm right up front with a baton." Odd is a spiritual guy, and in my experience, genuinely spiritual people--as opposed to those for whom faith is either a crutch or a bludgeon--have a great sense of humor. They recognize that our fallen world is not just tragic but also absurd, often hilariously absurd, and that laughing at humanity's hubris and reckless transgressive behavior is a potent way to deny legitimacy to that hubris. -

Conrad's Fiction As Critical Discourse by Richard Ambrosini

•«*#w* ""^^ "•"•sity ot Conrad's Fiction as Critical Discourse by Richard Ambrosini Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate Department of English University of Ottawa '^\ Richard Ambrosini, Ottawa, Canada, 1989. UMI Number: DC53558 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53558 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 1 Chapter One: Critical Discourse: The Five Tropes p. 26 Part I: The Preface to The Nigger of the "Narcissus" . p. 27 Part II: WORK p. 4 6 Part III: IDEALISM .... p. 61 Part IV: EFFECT p. 68 Part V: FIDELITY .... p. 80 Part VI: PRECISION . p. 8 9 Chapter Two: Working on Language and Structure: Alternative Strategies in Conrad's Choice of Authorship . p. 104 Chapter Three: The Mirror-Effect in "Heart of Darkness" p. 133 Chapter Four: Lord Jim (I): The Narrator as Interpreter . p. 180 Chapter Five: Lord Jim (II): The Narrator as Reader p. 240 Conclusion p. -

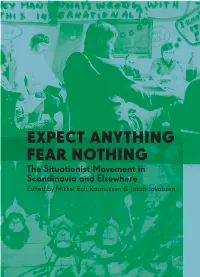

Expect Anything Fear Nothing the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1

ExpEct anything FEar nothing The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 ExpEcT AnyThing Fear noThing 2 ExpEcT AnyThing Fear noThing The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 ExpEcT AnyThing Fear noThing ThE SiTuaTionist MovemenT in Scandinavia and Elsewhere ExpEcT AnyThing Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen Fear noThing Published 2011 by nebula in association with autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia ThE SiTuaTionist MovemenT læssøegade 3,4 Po Box 568, williamsburgh Station dK-2200 copenhagen Brooklyn, nY 11211-0568 denmark uSa in Scandinavia www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] and Elsewhere Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 iSBn 978-87-993651-2-8 ISBn 978-1-57027-232-5 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina vishmidt | design: Åse Eg | Inserts: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Proofreading: Mikkel Bolt rasmussen Matt Malooly | Printed by: naryana Press in 2,000 copies | web: destroysi.dk & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: The Situationists Fighters (Mie lund hansen, anne Sophie Seiffert, Magnus Fuhr, Robert Kjær clausen, Johannes Balsgaard, Samuel willis nielsen, henrik Busk, david hilmer Rex, Tine Tvergaard, anders hvam waagø, Bue Thastrum, Johannes Busted larsen, Maibritt Pedersen, Kate vinter, odin Rasmussen, Tone andreasen, ask Katzeff and Kirsten Forkert), Peter laugesen, Jacqueline de Jong, Gordon Fazakerley, hardy Strid, Stewart home, Fabian Tompsett, Karen Kurczynski, lars Morell, Tom Mcdonough, Zwi & negator, lis Zwick, ulla Borchenius, henriette heise, Katarina Stenbeck, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jaya Brekke, James Manley, Matt Malooly, Åse Eg and Marina vishmidt. cover images: detourned photo by J.v. Martin of François de Beaulieu, René vienet, J.v. -

Like a Character in a Truffaut Film Trevor Lance Seigler Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2016 Like a Character in a Truffaut Film Trevor Lance Seigler Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Seigler, Trevor Lance, "Like a Character in a Truffaut Film" (2016). All Theses. 2319. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2319 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIKE A CHARACTER IN A TRUFFAUT STORY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English by Trevor Lance Seigler May 2016 Accepted by: Keith Lee Morris, Committee Chair Keith Lee Morris Nic Brown Dr. Joseph Mai i Abstract I composed these two stories in my two different Fiction Workshop classes, they both deal with mortality and the concept of what we do and how it affects others. I would like to think that they also exhibit some of the genre-bending notions I absorbed from reading Jonathan Lethem, who is the subject of the critical essay. ii Dedication To my mother, who never said “no” to any book that I wanted from the library. Also, to my niece, who is a storyteller in her own right. iii Acknowledgments I want to thank the members of my committee (Keith Lee Morris, Nic Brown, and Joseph Mai, as well as Jillian Weise) for pushing me to work for this degree, and to earn it through better writing. -

Silent Corner Discussion Questions by Dean Koontz

Silent Corner Discussion Questions by Dean Koontz Author Bio: (from Fantastic Fiction & Dean Koontz website) Dean Koontz is acknowledged as one of today's most celebrated and successful writers. His books are published in 38 languages and he has sold over 500 million copies to date. Dean Koontz lives in Southern California with his wife, Gerda, their golden retriever, Elsa, and the enduring spirit of their goldens, Trixie and Anna. Characters: Jane Hawk – Former FBI agent. Used to provide investigative support for the FBI Behavioral Science Unit. Widowed four months ago. Her husband, Nick, was a Marine. They have a son, Travis (5). Her mother is deceased. Her father is a famous musician. Mr. Drood – The alias of the man/group threatening Jane and Travis. Name taken from “A Clockwork Orange.” Kipp Garner – Radburn’s partner/henchman who enjoys violence. John Harrow – Special Agent in Charge of the LA FBI office. Nick Hawk – Former Marine. Unexpectedly and uncharacteristically kills himself with a knife. Married to Jane Hawk. Booth Hendrickson – Works in the Department of Justice. Becomes Silverman’s handler after his infection. Randolph Kohl – Director of Homeland Security. Gwyneth Lambert – Widow. Her husband, Gordon, was a former marine Lieutenant General who committed suicide. David James Michael – On the board of the Gernsback institute (What if Conference). Inherited a fortune. Venture capitalist who funds high tech startups – Shenneck’s technology and Far Horizons. William Sterling Overton – Lawyer. Friend/works for Senneck. Member of Aspasia. Jimmy Radburn – Hacker/cracker extraordinaire. Thinks of himself as a cyberspace pirate. His real name is Robert Branwick. -

Essays, Book I

Essays, Book I Michel de Montaigne 1580 Copyright © Jonathan Bennett 2017. All rights reserved [Brackets] enclose editorial explanations. Small ·dots· enclose material that has been added, but can be read as though it were part of the original text. Occasional •bullets, and also indenting of passages that are not quotations, are meant as aids to grasping the structure of a sentence or a thought. Every four-point ellipsis . indicates the omission of a brief passage that seems to present more difficulty than it is worth. Longer omissions are reported between brackets in normal-sized type. —Montaigne kept adding to this work. Following most modern editions, the present version uses tags in the following way: [A]: material in the first edition (1580) or added soon thereafter, [B]: material added in the greatly enlarged second edition (1588), [C]: material added in the first posthumous edition (1595) following Montaigne’s notes in his own copy. The tags are omitted where they seem unimportant. The ones that are retained are kept very small to make them neglectable by readers who aren’t interested in those details. Sometimes, as on pages 34 and 54, they are crucial. —The footnotes are all editorial. —Montaigne’s spellings of French words are used in the glossary and in references in the text to the glossary. —In the original, all the quotations from Latin writers are given in Latin. First launched: 2017 Contents 1. We reach the same end by different means 2 2. Sadness 4 3. Our feelings reach out beyond us 5 Essays, Book I Michel de Montaigne 4. -

Bibliography of Reviews of the Works for Dean Koontz As Removed from the Manuscript of the Collectors Guide to Dean Koontz by Michael P

A (very incomplete) Bibliography of reviews of the works for Dean Koontz as removed from the manuscript of The Collectors Guide to Dean Koontz by Michael P. Sauers to be published by Cemetery Dance Publications in 2011 The story behind this document can be found @ http://www.travelinlibrarian.info/CGTDK/2010/08/12/review-removal/ After the Last Race by Dean R. Koontz Reviews Kirkus Reviews v42 Sept. 1, 1974 p961 Publisher’s Weekly v206 Sept. 23, 1974 p148 Library Journal v99 Oct. 1, 1974 p2505 NEW YORK TIME BOOK REVIEW Jan. 12,1975 p18 Best Sellers v34 Feb. 1, 1975 p498 Publisher’s Weekly v208 Nov. 17, 1975 p99 Anti-Man by Dean R. Koontz Reviews Luna Monthly 26/27:33 Jl/Aug 1971 -Evers, J. The Bad Place by Dean R. Koontz Reviews New York Times Feb. 08,1989 pC26 -McDowell, E. Kirkus Reviews v57 Nov. 1, 1989 p1551 Booklist v86 Nov. 15, 1989 p618 Publisher’s Weekly Nov. 24,1989 p59 -Steinberg, S. Library Journal v114 Dec 1989 p170 (2) -Annichiarico, Mark Connoisseur v219 Dec 1989 p40 -Sawhill, Ray Rave Reviews #22, Dec/Jan (1989/90) p71 -Frank A. LaPorto The Blood Review v1 #2, Jan 1990 p51 -Richard Wellgosh The Blood Review v1 #2, Jan 1990 p51 -Mark Grahm West Coast Review of Books v15 #3 1990 p29 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Jan 21 1990 sec N p8 -Janet Ward LA Times Book Review Jan. 21, 1990 p12 Boston Globe Jan 25 1990 p75 -Bob MacDonald San Francisco Chronicle Feb 4 1990 sec REV p6 -Leila Raim New York Times Book Review Feb. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. I.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When. a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Philosophy and Literature 25

Joseph Carroll 295 Joseph Carroll THE ECOLOGY OF VICTORIAN FICTION I n the past ten years or so, ecological literary criticism—that is, Icriticism concentrating on the relationship between literature and the natural environment—has become one of the fastest-growing areas in literary study. Ecocritics now have their own professional association, their own academic journal, and an impressive bibliography of schol- arly studies. Ecocritical scholars divide their attention between “nature writing” and ecological themes within all literature. In other words, some scholars write on Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Annie Dillard; others write on topics such as the representation of nature in romantic poetry, the American West as a symbol, metaphors of land- scape, or Dante’s Inferno as a polluted ecosystem. Ecocritics have a distinct subject matter, and they share in a certain broad set of attitudes, values, and public policy concerns, but they do not yet have a firmly established framework of commonly accepted theoretical principles. In the absence of any overarching theory, ecocritics have usually sought to incorporate their ecological subject matter within other, already estab- lished theoretical schools: feminism, Bakhtin’s dialogism, Lacanian psychoanalysis, or English romantic and American transcendentalist, idealist philosophy. Most commonly, ecocritics have affiliated them- selves with the standard contemporary blend of Foucauldian ideologi- cal criticism—a blend that is vaguely Marxist and Freudian, generally radical, and strongly tinctured with deconstructive irrationalism and textualism.1 Given its specialized themes and topics and its ready affiliation with the standard theoretical blend, ecocriticism might seem little more than a special topic area within the general field of contemporary Philosophy and Literature, © 2001, 25: 295–313 296 Philosophy and Literature literary study. -

Seize the Night Free Download

SEIZE THE NIGHT FREE DOWNLOAD Dean Koontz | 512 pages | 03 Jun 1999 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780747258339 | English | London, United Kingdom Seize the Night Yes, he did. The characters are a little too perfect and have absolutely no flaws, and are therefore not human. Superstition is the dark side of wonder. With his small and once peaceful town of Moonlight Bay becoming more and Seize the Night strange, Chris is afraid to go to the police, not knowing if they are in on the kidnapping. It's too bad, and it makes for an unsatisfactory Seize the Night. Definitely recommended! Christopher Snow and Dean Koontz rock! See all 3 questions about Seize the Night…. Dean, the author of many 1 New York Times bestsellers, lives in Southern California with his wife, Gerda, their golden retriever, Elsa, and the enduring spirit of their goldens, Trixie and Anna. I outgrew Koontz a while ago not to say he isn't good, just that I began to be able to predict where he was going but this book, and its predecessor remain two of my all time favorites. Looking for More Great Reads? Never before in Dean Koontz's phenomenal writing career has he created a character quite like Christopher Snow: a creation so Seize the Night, so fascinating that the author has felt compelled to return to him. I love the combination of horror, sci-fi, and humor in this story. Sole Survivor. Vicious, genetically-altered, man-attacking Rhesus monkeys; a product of a secret government program based on the main character's dead mother's work in theoretical genetics. -

Dean Koontz Dean Koontz

DEANDEAN KOONTZKOONTZ d Bantam Books / New York THE WHISPERING ROOM A Jane Hawk Novel BY DEAN KOONTZ Ashley Bell • The City • Innocence • 77 Shadow Street What the Night Knows • Breathless • Relentless Your Heart Belongs to Me • The Darkest Evening of the Year The Good Guy • The Husband • Velocity • Life Expectancy The Taking • The Face • By the Light of the Moon One Door Away From Heaven • From the Corner of His Eye False Memory • Seize the Night • Fear Nothing Mr. Murder • Dragon Tears • Hideaway • Cold Fire The Bad Place • Midnight • Lightning • Watchers Strangers • Twilight Eyes • Darkfall • Phantoms Whispers • The Mask • The Vision • The Face of Fear Night Chills • Shattered • The Voice of the Night The Servants of Twilight • The House of Thunder The Key to Midnight • The Eyes of Darkness Shadowfires • Winter Moon • The Door to December Dark Rivers of the Heart • Icebound • Strange Highways Intensity • Sole Survivor • Ticktock The Funhouse • Demon Seed JANE HAWK The Silent Corner • The Whispering Room ODD THOMAS Odd Thomas • Forever Odd • Brother Odd • Odd Hours Odd Interlude • Odd Apocalypse • Deeply Odd • Saint Odd FRANKENSTEIN Prodigal Son • City of Night • Dead and Alive Lost Souls • The Dead Town A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog Named Trixie The Whispering Room is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2018 by Dean Koontz All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.