Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usama Bin Ladin's

Usama bin Ladin’s “Father Sheikh”: Yunus Khalis and the Return of al-Qa`ida’s Leadership to Afghanistan Harmony Program Kevin Bell USAMA BIN LADIN’S “FATHER SHEIKH:” YUNUS KHALIS AND THE RETURN OF AL‐QA`IDA’S LEADERSHIP TO AFGHANISTAN THE COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT www.ctc.usma.edu 14 May 2013 The views expressed in this paper are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government. Author’s Acknowledgments This report would not have been possible without the generosity and assistance of the director of the Harmony Research Program at the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC), Don Rassler. Mr. Rassler provided me with the support and encouragement to pursue this project, and his enthusiasm for the material always helped to lighten my load. I should state here that the first tentative steps on this line of inquiry were made during my time as a student at the Program in Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. If not for professor Şükrü Hanioğlu’s open‐minded approach to directing my MA thesis, it is unlikely that I would have embarked on this investigation of Yunus Khalis. Professor Michael Reynolds also deserves great credit for his patience with this project as a member of my thesis committee. I must also extend my utmost appreciation to my reviewers—Carr Center Fellow Michael Semple, professor David Edwards and Vahid Brown—whose insightful comments, I believe, have led to a substantially improved and more thoughtful product. -

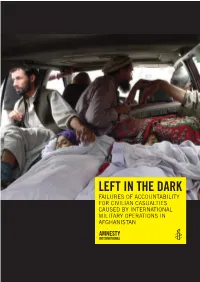

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

DEWS WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL REPORT EPREPORT SUMMARY: This Report Includes Surveillance Data from 4Th July to 10Th August 2012

August 13, 2012 DISEASES EARLY WARNING SYSTEM WER-32(6th Yr) DEWS WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL REPORT EPREPORT SUMMARY: th th This report includes surveillance data from 4 July to 10 August 2012. Out of 312 functional Sentinel sites(SS), all 312 (100%) have sent their reports in Week-32 of 2012; Out of total 274,261 Consultations recorded in week-32 of 2012, 90,745 (33.1%) consultations were reported due to DEWS target diseases. Main causes of consultations this week are Acute Respiratory Infections/ARI (13.6%) and Acute Diarrheal Diseases/ADD (17.6%) from total clients in a continuing trend from the week before. 52 deaths caused due to Pneumonia, Diarrheal diseases and Meningitis/Severely ill children, so that 19 deaths due to pneumonia, 20 deaths due to diarrheal diseases and 13 deaths reported due to Meningitis and Severely Ill Children. In this reporting week, three Measles outbreaks reported and investigated in Laghman, Zabul and Urozgan provinces. No other outbreaks have been reported in this reporting week. REPORTS RECEIVED FROM REPORTING SITES: As of August 10, 2012, 312 sentinel sites were functioning in eight epidemiological regions, in 34 provinces of Afghanistan . In this reporting week, all 312 sentinel sites have sent their reports on new cases of DEWS target diseases , recorded during the reporting. Out of all events recorded in DEWS sentinel sites, 15 target diseases (priority diseases) are included in DEWS weekly epidemiological reports. Table-1: Status of Reports Received from DEWS Regions during Epidemiological week-32, 2012 Central East Central West North North East West South East South East Total No. -

Punishment Before Justice: Indefinite Detention in the US

Physicians for Human Rights Punishment Before Justice: Indefinite Detention in the US June 2011 physiciansforhumanrights.org ABOUT PHYSICIANS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS inside frontPhysicians for Human Rights (PHR) is an independent, non-profit orga- cover nization that uses medical and scientific expertise to investigate human rights violations and advocate for justice, accountability, and the health and dignity of all people. We are supported by the expertise and passion of health professionals and concerned citizens alike. Since 1986, PHR has conducted investigations in more than 40 countries around the world, including Afghanistan, Congo, Rwanda, Sudan, the United States, the former Yugoslavia, and Zimbabwe: 1988 — First to document Iraq’s use of chemical weapons against Kurds 1996 — Exhumed mass graves in the Balkans 1996 — Produced critical forensic evidence of genocide in Rwanda 1997 — Shared the Nobel Peace Prize for the International Campaign to Ban Landmines 2003 — Warned of health and human rights catastrophe prior to the invasion of Iraq 2004 — Documented and analyzed the genocide in Darfur 2005 — Detailed the story of tortured detainees in Iraq, Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay 2010 — Presented the first evidence showing that CIA medical personnel engaged in human experimentation on prisoners in violation of the Nuremberg Code and other provisions ... 2 Arrow Street | Suite 301 Cambridge, MA 02138 USA 1 617 301 4200 1156 15th Street, NW | Suite 1001 Washington, DC 20005 USA 1 202 728 5335 physiciansforhumanrights.org ©2011, Physicians for Human Rights. All rights reserved. Front cover photo: JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty Images ISBN:1-879707-62-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927978 Bahrain: Medical Neutrality Acknowledgments The lead author for this report is Cara M. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

Report 2013–1124

Prepared in cooperation with the Afghan Geological Survey under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations Topographic and Hydrographic GIS Datasets for the Afghan Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey 2013 Mineral Areas of Interest Open-File Report 2013–1124 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photo showing mountainous terrain and the alluvial floodplain of a small tributary in the upper reaches of the Kabul River Basin located northeast of Kabul Afghanistan, 2004 (Photograph by Peter G. Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey). Topographic and Hydrographic GIS Datasets for the Afghan Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey 2013 Mineral Areas of Interest By Brittany N. Casey and Peter G. Chirico Open-File Report 2013–1124 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2013 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. -

Afghan Forces Recapture Commander in Paktia Badakhshan’S Yamgan District

Page2 2 Main News Page Airstrike Kills Key Taliban Afghan Forces Recapture Commander in Paktia Badakhshan’s Yamgan District KABUL - A key Taliban com- on Monday afternoon. mander, Allah Noor, was killed Provincial police spokesman along seven other militants Sardar Wali Tabasom told Ari- in airstrikes conducted by the ana News that three other Tali- Resolute Support mission in ban militants were also among eastern Paktia province, a po- the deaths. lice official said on Tuesday. The three Taliban commanders The operation was conducted identified as Zahid also known in Sarkal village of Aryob Zazi as Fedaee, Shamal known as district over Taliban hideouts Wafadar, ...(More on P4)...(9) 7 Taliban Killed, 12 Injured by Own Bomb PUL-I-ALAM - Seven Tali- nor’s spokesman, Didar La- ban militants were killed and wang. a dozen more injured when a He told Pajhwok Afghan News bomb they were making went that the militants were busy off prematurely in central Log- making bombs inside a home KABUL - Afghan forces recap- day. A MoD statement said the after four years. brave Afghan forces were pro- ar province last night, an offi- when one of the explosive de- tured Yamgan district of north- district was recaptured as a re- The Taliban sustained heavy gressing and continuing opera- cial said on Monday. vices exploded. eastern Badakhshan province sult of airstrikes and ground op- losses and many of their fighters tions in Badakhshan against the The incident happened in However, the Taliban have so on Monday after four years, the erations and Afghan national flag surrendered to ANDSF, the state- enemies of peace and stability. -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. -

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR)

Special Inspector General for OCT 30 SIGAR Afghanistan Reconstruction 2018 QUARTERLY REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS The National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2008 (Pub. L. No. 110- 181) established the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR). SIGAR’s oversight mission, as dened by the legislation, is to provide for the independent and objective • conduct and supervision of audits and investigations relating to the programs and operations funded with amounts appropriated or otherwise made available for the reconstruction of Afghanistan. • leadership and coordination of, and recommendations on, policies designed to promote economy, efciency, and effectiveness in the administration of the programs and operations, and to prevent and detect waste, fraud, and abuse in such programs and operations. • means of keeping the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense fully and currently informed about problems and deciencies relating to the administration of such programs and operation and the necessity for and progress on corrective action. Afghanistan reconstruction includes any major contract, grant, agreement, or other funding mechanism entered into by any department or agency of the U.S. government that involves the use of amounts appropriated or otherwise made available for the reconstruction of Afghanistan. As required by the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2018 (Pub. L. No. 115-91), this quarterly report has been prepared in accordance with the Quality Standards for Inspection and Evaluation issued by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efciency. Source: Pub.L. No. 110-181, “National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2008,” 1/28/2008, Pub. L. No. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and by creating opportunities for analysis, thought and debate. -

The Constitutional and Political Clash Over Detainees and the Closure of Guantanamo

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH LAW REVIEW Vol. 74 ● Winter 2012 PRISONERS OF CONGRESS: THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CLASH OVER DETAINEES AND THE CLOSURE OF GUANTANAMO David J.R. Frakt ISSN 0041-9915 (print) 1942-8405 (online) ● DOI 10.5195/lawreview.2012.195 http://lawreview.law.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D- Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. PRISONERS OF CONGRESS: THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CLASH OVER DETAINEES AND THE CLOSURE OF GUANTANAMO David J.R. Frakt Table of Contents Prologue ............................................................................................................... 181 I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 183 A. A Brief Constitutional History of Guantanamo ................................... 183 1. The Bush Years (January 2002 to January 2009) ....................... 183 2. The Obama Years (January 2009 to the Present) ........................ 192 a. 2009 ................................................................................... 192 b. 2010 to the Present ............................................................. 199 II. Legislative Restrictions and Their Impact ................................................... 205 A. Restrictions on Transfer and/or Release