Krugman SP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POEMS by Erin Louise Shaffer This Collection of Poems Attempts To

ABSTRACT WHAT’S MISSED: POEMS by Erin Louise Shaffer This collection of poems attempts to illustrate that despite the possible pain of an examined life, through it, greater levels of meaning can be revealed. They tend towards a narrative mode, but are also interested in lyric methods of presenting the small agonies and joys of human existence. The poems are attuned to presenting the beauty and meaning of the everyday with a voice of humor, wit and sincerity, and are deeply concerned with character. They reflect attention to the accretion of detail. It is important that they be morning glories and hyacinths, not just flowers. The reader is invited to the same level of conscientiousness with which the speakers in these poems experience the world. These works aspire to help others see mirrors of their own experience and motivate them to create their own paths to understanding. WHAT’S MISSED: POEMS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Erin Louise Shaffer Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor________________________________ Mr. David Schloss Reader_________________________________ Dr. Andrew Osborn Reader_________________________________ Mr. James Reiss Contents I. Damselfly Wings Noon 2 Lake Nakuru 3 Watamu, Kenya 4 Angel 5 Almost to Anger 6 Not Postmarked Diani Beach 7 Scrapbook 8 After the Tornado 9 Mean 11 Unpacking 12 Cinderella After Midnight 13 Refrain 14 For Ralph, on the Other Side of the Duplex 15 After Dinner 16 II. Popsicles Red 18 Crabapple 19 The Billy Graham Crusade 20 Lookout 21 Neighborhood Gossip 22 Qualifying Time 24 Decoration Day 25 Goodbye, Neighbor 26 III. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

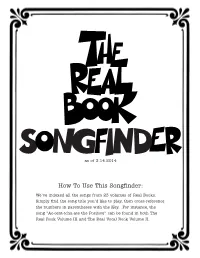

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2016 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 26 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book (The Bird Book)/00240358 C Instruments/00240221 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 BCb Instruments/00240226 13. The Real Christmas Book – 2nd Edition Mini C Instruments/00240292 C Instruments/00240306 Mini B Instruments/00240339 B Instruments/00240345 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 Eb Instruments/00240346 C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks BCb Instruments/00240347 Flash Drive/00110604 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 02. The Real Book – Volume II 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Eb Instruments/00240228 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 BCb Instruments/00240229 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 03. The Real Book – Volume III 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 C Instruments/00240233 21. The Real Blues Book/00240264 B Instruments/00240284 22. -

Where Do the Ducks Go? by Alyssa Schwenk and the Females Are Mottled Brown

Powder and wig presents 'The Elephant Man," See p. 10. Decision not expected until end of semester By David Holtzman her to meet with Presidents' Council STAFF WRITER to discuss the matter. m^^^^ BmmmmWt^mmWi ^mfMMa ^m mmniemKMMmmmmmmB ^sBm *simmmmm^m *m "That party was very difficult to After the President's Council control," she said. She decided on went into executive session last the morning of the 28th, before week to discuss the alcohol debate, Dupuis' accident, to have a security Student Association President officer posted at the kegs that Shawn Crowley said the ongoing evening. battle over the alcohol policy was At its October meeting the Board "as intense as it's been since my of Trustees voiced concern over the freshman year." alcohol issue, causing the college to But, neither Stu-A nor Dean of consider taking action to curb photo by Josh Friedman Students Janice Seitzinger anticipate uncontrolled drinking. Panelists Mark Van Valkenburgh, Dr. David. Hume, and Janice Seitzinger f ieldtoug h questions at the alcohol f orum. drawing any firm conclusions before "Alcohol is always a problem at the end of the semester. Colby, as at any college," David It s still up m the air - still in the Pulver '63 said. "We're always Forum airs frustrations, solves nothing early stages," said Crowley. "We concerned about it." havebasically until January to come The Student Affairs Committee By Amira Bahu Student Activities Social Chair Patty monies to a school if they are pro- up with something." here at the college will work to STAFF WRITER Masters '91. -

Still Crazy: an Unsung Homage to the New Testament

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 8 Issue 3 October 2004 Article 5 October 2004 Still Crazy: An Unsung Homage to the New Testament Mary Ann Beavis St. Thomas More College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Beavis, Mary Ann (2004) "Still Crazy: An Unsung Homage to the New Testament," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 8 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol8/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Still Crazy: An Unsung Homage to the New Testament Abstract This article argues that the British rock-and-roll comedy Still Crazy (1998) is based on the New Testament similarly to the way that Clueless is related to Jane Austen's Emma, or The Legend of Bagger Vance is related to the Bhagavad Gita. A detailed comparison of the characters, settings and incidents (as well as explicit references) in the film ot elements in the New Testament and related Christian traditions is offered to support this thesis. Thus, Still Crazy is of interest to scholars of religion and film, and is particularly useful for teaching purposes. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol8/iss3/5 Beavis: Still Crazy Still Crazy is a British rock-and roll comedy that attracted -

Brio 46.2 V4

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Mera, M. and Winters, B. (2009). Film and Television Music Sources in the UK and Ireland. Brio: Journal of the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres., 46(2), pp. 37-65. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13661/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Mera, M & Winters, B (2009). Film Music Sources in the UK and Ireland. Brio: Journal of the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres., 46(2), City Research Online Original citation: Mera, M & Winters, B (2009). Film Music Sources in the UK and Ireland. Brio: Journal of the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres., 46(2), Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/13590/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z. -

Music List (PDF)

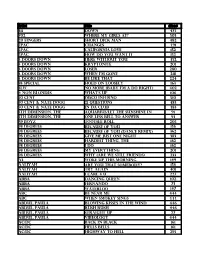

Artist Title disc# 311 Down 475 702 Where My Girls At? 503 20 fingers short dick man 482 2pac changes 491 2Pac California Love 152 2Pac How Do You Want It 152 3 Doors Down Here Without You 452 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 201 3 doors down loser 280 3 Doors Down when I'm gone 218 3 Doors Down Be Like That 224 38 Special Hold On Loosely 163 3lw No more (baby I'm a do right) 402 4 Non Blondes What's Up 106 50 Cent Disco Inferno 510 50 cent & nate dogg 21 questions 483 50 cent & nate dogg in da club 483 5th Dimension, The aquarius/let the sunshine in 91 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 93 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 205 98 Degrees Because Of You 156 98 Degrees Because Of You (Dance Remix) 362 98 degrees Give me just one Night 383 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, the 162 98 Degrees I Do 162 98 Degrees My Everything 201 98 Degrees Why (Are We Still Friends) 233 A3 Woke Up This Morning 149 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? 156 aaliyah Try again 401 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 227 Abba Dancing Queen 102 ABBA FERNANDO 73 ABBA Waterloo 147 ABC Be Near Me 444 ABC When Smokey Sings 444 ABDUL, PAULA Blowing Kisses In The Wind 446 ABDUL, PAULA Rush Rush 446 ABDUL, PAULA STRAIGHT UP 27 ABDUL, PAULA Vibeology 444 AC/DC Back In Black 161 AC/DC Hells Bells 161 AC/DC Highway To Hell 295 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 295 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 295 AC/dc You shook me all night long 108 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 8 Ace of Base Don't Turn Around 154 Ace Of Base Sign, The 206 AD LIBS BOY FROM NEW YORK CITY, THE 49 adam ant goody two shoes 108 ADAMS, BRYAN (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU -

International Society of Quarterly

International Society of Volume 44 Number 3 Are We Still A ProfeSSion? Sir Sydney Kentridge A ford, not A lincoln: reminiScenceS About the 38th PreSident Thomas M. DeFrank humAn Stem cell reSeArch: ProgreSS, PromiSe, And PoliticS James M. Bowen WorldS Apart Mark Kline Quarterly International Society of Barristers Quarterly Volume 44 July 2009 Number 3 CONTENTS Are We Still a Profession? ............................. Sir Sydney Kentridge ...... 397 A Ford, Not a Lincoln: Reminiscences About the 38th President ..... Thomas M. DeFrank ....... 409 Human Stem Cell Research: Progress, Promise, and Politics .................... James M. Bowen ............. 421 Worlds Apart .................................................. Mark Kline ...................... 434 International Society of Barristers Quarterly Editor John W. Reed Associate Editor Margo Rogers Lesser Editorial Advisory Board Daniel J. Kelly James K. Robinson J. Graham Hill, ex officio Editorial Office University of Michigan Law School Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1215 Telephone: (734) 763-0165 Fax: (734) 764-8309 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 44 Issue Number 3 July, 2009 The INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BARRISTERS QUARTERLY (USPS 0074-970) (ISSN 0020- 8752) is published quarterly by the International Society of Barristers, University of Michigan Law School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1215. Periodicals postage is paid at Ann Arbor and additional mailing offices. Subscription rate: $10 per year. Back issues and volumes available from William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14209-1911. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the International Society of Barristers, University of Michigan Law School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1215. ©2009 International Society of Barristers International Society of Barristers Board of Governors 2009* William F. Martson, Jr., Oregon, President Marietta S. -

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2014 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 23 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 08. The Real Blues Book/00240264 C Instruments/00240221 09. Miles Davis Real Book/00240137 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book/00240358 BCb Instruments/00240226 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 Mini C Instruments/00240292 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 Mini B Instruments/00240339 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 13. The Real Christmas Book C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks C Instruments/00240306 Flash Drive/00110604 B Instruments/00240345 Eb Instruments/00240346 02. The Real Book – Volume II BCb Instruments/00240347 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 Eb Instruments/00240228 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 BCb Instruments/00240229 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 03. The Real Book – Volume III 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 C Instruments/00240233 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 B Instruments/00240284 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 Eb Instruments/00240285 BCb Instruments/00240286 21. -

David Halberstam Honore D

See Vthja ^^ food? page 5v David Halberstam honore d Faculty votes in favor of BY JILL MORNEAU NCAA competition Staff Writer Maisel submitted a substitute BY AMY MONTEMERLO motion which addressed many Colby honored Pulitzer Prize .News Editor areas of athletics at Colby. The winning journalist David substitute resolution contains six Halberstam for his work in Viet- Colby faculty voted to sup- principles Which . the Athletics nam and the Civil Rights Move- port continued participation in Advisory Comrnittee feels that ment at the 45th annual Elijah NCAA post-season athletic com- NESCAC presidents should ad- Parish Lovejoy Convocation on petitionlastWednesday,Novem- here to including: the NESCAC Thursday, November 13. ber 12. This vote, which SGA conference of liberal arts schools President William Cotter be- President Shannon Baker '98 con- should remain intact, the success gan the ceremony by remember- sidered "shocking," coincides of NESCAC as a scheduling con- ing the man,' Elijah Parish with the opinions of the majority ference should be universally ap- Lovejoy, for whom the award had of Colby students and athletes plied to all sports, restrictions been created. Lovejoy, a gradu- regarding this controversial is- placed on student athletes should ate of Colby, lost his life defend- sue. On December 11, President be re-examined in regards to up- ing his press against pro-slavery Cotter, along with the presidents holdingthe "primacy of academic laws in Alton, Illinois. Cotter ex- of the eight other NESCAC insti- programs over athletic pro- plained that the work of David tutions, will decide the status of grams," that no. NESCAC team Halberstam exemplifies the four year experiment which may participate in national com- Lovejoy's words and that allowed athletic teams from petition if it runs interference with Halberstam is "driven by a pas- NESCAC colleges to participate final examinations, thatNESCAC sion for work." in NCAA post-season athletic athletic directors re-examine Halberstafn humbly accepted competition. -

The Trinity Reporter, Fall 2019

The Westonian Magazine The Westonian The Trinity Reporter The Trinity The Trinity Reporter FALL 2019 Lessons LEARNED Understanding ‘richness of the human experience’ through study of history ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: Women at the Summit: 50 Years of Coeducation at Trinity College FALL 2019 FALL SPRING 2014 CONTENTS FEATURES 14 Women at the Summit: 50 Years of Coeducation at Trinity College Women at Trinity Here and now … and looking toward tomorrow 20 Understanding addiction Laura Holt ’00 and her Trinity students study the psychology of vaping 24 Lessons learned Understanding ‘richness of the human experience’ through study of history 28 Sharing patients’ stories Memoir by Eric Manheimer ’71 leads to small-screen success with NBC’s New Amsterdam 32 Annual giving Strengthening Trinity—together ON THE COVER People and places of the past represent the importance to the future of studying history. For more, please see page 24. ILLUSTRATION: ELEANOR SHAKESPEARE WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! The Trinity Reporter welcomes letters related to items published in recent issues. Please send remarks to the editor at [email protected] or Sonya Adams, Office of Communications, Trinity College, 300 Summit Street, Hartford, CT 06106. DEPARTMENTS 02 ALONG THE WALK 06 AROUND HARTFORD 10 TRINITY TREASURE 11 VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT 37 CLASS NOTES 69 IN MEMORY 76 ALUMNI EVENTS 80 ENDNOTE THE TRINITY REPORTER Vol. 50, No. 1, Fall 2019 Published by the Office of Communications, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 06106. Postage paid at Hartford, Connecticut, and additional mailing offices. The Trinity Reporter is mailed to alumni, parents, faculty, staff, and friends of Trinity College without charge.