Printer-Friendly .Pdf Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockbuster Welterweight Bout Between Conor Mcgregor and Cowboy Cerrone Headlines Ufc® 246 in Las Vegas

BLOCKBUSTER WELTERWEIGHT BOUT BETWEEN CONOR MCGREGOR AND COWBOY CERRONE HEADLINES UFC® 246 IN LAS VEGAS Las Vegas – UFC® will kick off 2020 with a thrilling bout featuring former lightweight and featherweight champion Conor McGregor and perennial fan favorite Donald “Cowboy” Cerrone. Plus, former UFC lightweight champion and No. 11 ranked contender Anthony Pettis will return to 155 pounds against surging Diego Ferreira. UFC® 246: MCGREGOR vs. COWBOY will take place Saturday, Jan. 18 at T-Mobile Arena and will stream live nationally on Pay-Per- View, exclusively through ESPN+ in the U.S. at 10 p.m. ET/7 p.m. PT in both English and Spanish. ESPN+ is the exclusive provider of all UFC Pay-Per-View events to fans in the U.S. as part of an agreement that continues through 2025. As UFC® 246: MCGREGOR vs. COWBOY approaches, fans will be able to purchase itonline at ESPNPlus.com/PPV or on the ESPN App on mobile and connected-TV devices. ESPN+ is available as an integrated part of the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected-TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Preliminary fights will air nationally in English on ESPN and on ESPN Deportes (in Spanish) starting at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT with the early prelims simulcast on UFC Fight Pass and ESPN+ at 6:15 p.m. ET/3:15 p.m. PT. Arguably the biggest star in mixed martial arts history, McGregor (21-4, fighting out of Dublin, Ireland) became the first fighter in UFC history to simultaneously hold championships in two divisions. -

Uzbek: War, Friendship of the Peoples, and the Creation of Soviet Uzbekistan, 1941-1945

Making Ivan-Uzbek: War, Friendship of the Peoples, and the Creation of Soviet Uzbekistan, 1941-1945 By Charles David Shaw A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor Professor Victoria E. Bonnell Summer 2015 Abstract Making Ivan-Uzbek: War, Friendship of the Peoples, and the Creation of Soviet Uzbekistan, 1941-1945 by Charles David Shaw Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair This dissertation addresses the impact of World War II on Uzbek society and contends that the war era should be seen as seen as equally transformative to the tumultuous 1920s and 1930s for Soviet Central Asia. It argues that via the processes of military service, labor mobilization, and the evacuation of Soviet elites and common citizens that Uzbeks joined the broader “Soviet people” or sovetskii narod and overcame the prejudices of being “formerly backward” in Marxist ideology. The dissertation argues that the army was a flexible institution that both catered to national cultural (including Islamic ritual) and linguistic difference but also offered avenues for assimilation to become Ivan-Uzbeks, part of a Russian-speaking, pan-Soviet community of victors. Yet as the war wound down the reemergence of tradition and violence against women made clear the limits of this integration. The dissertation contends that the war shaped the contours of Central Asian society that endured through 1991 and created the basis for thinking of the “Soviet people” as a nation in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Tc/Cop3/Inf.6

TC TC/COP3/INF.6 Framework Convention Dist.: General for the Protection of the Marine 12 August 2011 Original: English Environment of the Caspian Sea CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Third Meeting Aktau, 10-12 August 2011 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS SURNAME, POSITION, ADRESS CONTACT NAME ORGANIZATION REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN 1. Mr.Rauf Hajiyev Deputy Minister of Ecology Agayev str. 100A, Tel: + 99412 492 59 07 and Natural Resources of the AZ1073 Fax: + 99412 492 59 07 Republic of Azerbaijan Baku, Azerbaijan 2. Mr. Mehman Director, Fisheries Institute, Azerbaijan, Baku, Tel / Fax: +99412 4963037 Akhundov Ministry of Ecology and AZ1008, E-mail: [email protected] Natural Resources of the Demirchizade str., Republic of Azerbaijan 16 3. Mr.Azad Jafarli Second Secretary 4, Sh. Gurbanov Tel: + 99451 8673 227 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Str., AZ 1009 Email: [email protected] the Republic of Azerbaijan Baku, Azerbaijan 4. Ms.Konul Expert Agayev str. 100A, Tel: +99412 498 23 46 Ahmadova Ministry of Ecology and AZ1073 Fax: +99412 492 59 07 Natural Resources of the Baku, Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan 5. Elkhan Zeinalov Consul, Consulate of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Aktau ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN 6. Mr. Mohammad Vice-President and Head of Pardisan Nature Javad Department of Environment Park, Hakim Mohammadizadeh Highway, Tehran 7. Mr. Shafie Pour Acting Head of the DOE on Pardisan Nature International Affairs and Park, Hakim Conventions Highway, Tehran 8. Mr.Mohammad Deputy Head of DOE for Pardisan Nature +98 2188233148 Bagher Nabavi Marine Environment Park, Hakim [email protected] Highway, Tehran 9. Mr.Gholamreza International Expert, Ministry MFA + 98 21 61154092 Hashemi of Foreign Affairs Tehran [email protected] 10. -

Amnesty International Report 2020/21

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. Amnesty International is impartial. We take no position on issues of sovereignty, territorial disputes or international political or legal arrangements that might be adopted to implement the right to self- determination. This report is organized according to the countries we monitored during the year. In general, they are independent states that are accountable for the human rights situation on their territory. First published in 2021 by Except where otherwise noted, This report documents Amnesty Amnesty International Ltd content in this document is International’s work and Peter Benenson House, licensed under a concerns through 2020. 1, Easton Street, CreativeCommons (attribution, The absence of an entry in this London WC1X 0DW non-commercial, no derivatives, report on a particular country or United Kingdom international 4.0) licence. territory does not imply that no https://creativecommons.org/ © Amnesty International 2021 human rights violations of licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode concern to Amnesty International Index: POL 10/3202/2021 For more information please visit have taken place there during ISBN: 978-0-86210-501-3 the permissions page on our the year. -

Annual Report 2011 Annual Report 2011

Norwegian Helsinki Committee Annual Report 2011 Annual Report 2011 Norwegian Helsinki Committee Established in 1977 The Norwegian Helsinki Committee (NHC) is a non-governmental organisation that works to promote respect for human rights, nationally and internationally. Its work is based on the conviction that documentation and active promotion of human rights by civil society is needed for states to secure human rights, at home and in other countries. The work of the NHC is based on the Helsinki Declaration, which was signed by 35 European and North American states at the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) in 1975. The declaration states that respect for human rights is a key factor in the development of peace and understanding between states. The main focal areas of the NHC are the countries of Europe, North America and Central Asia. The NHC works irrespective of ideology or political system in these countries and maintains political neutrality. How wE work Human rigHts monitoring and reporting Through monitoring and reporting on problematic human rights situations in specific countries, the NHC sheds light on violations of human rights. The NHC places particular emphasis on civil and political rights, including the fundamental freedoms of expression, belief, association and assembly. On-site research and close co-operation with key civil society actors are our main working methods. The NHC has expertise in election observation and has sent numerous observer missions to elections over the last two decades. support of democratic processes By sharing knowledge and with financial assistance, the NHC supports local initiatives for the promotion of an independent civil society and public institutions as well as a free media. -

The Berlin Radio War: Broadcasting in Cold War Berlin and the Shaping of Political Culture in Divided Germany, 1945- 1961

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE BERLIN RADIO WAR: BROADCASTING IN COLD WAR BERLIN AND THE SHAPING OF POLITICAL CULTURE IN DIVIDED GERMANY, 1945- 1961 Nicholas J. Schlosser, Ph.D. 2008 Dissertation Directed By: Professor Jeffrey Herf, Department of History This dissertation explores how German radio journalists shaped political culture in the two postwar Germanys. Specifically, it examines the development of broadcast news reporting in Berlin during the first sixteen years of the Cold War, focusing on the reporters attached to the American sponsored station RIAS 1 Berlin and the radio stations of the German Democratic Republic. During this period, radio stations on both sides of the Iron Curtain waged a media war in which they fought to define the major events of the early Cold War. The tension between objectivity and partisanship in both East and West Berlin came to define this radio war. Radio stations constantly negotiated this tension in an attempt to encourage listeners to adopt a specific political worldview and forge a bond between broadcaster and listener. Whereas East German broadcasters ultimately eschewed objectivity in favor of partisan news reporting defined by Marxist- Leninist ideology, RIAS attempted to combine factual reporting with concerted efforts to undermine the legitimacy of the German Democratic Republic. The study contributes to a number of fields of study. First, I contribute to scholarship that has examined the nature, development, and influence of political culture. 1 Radio in the American Sector Related to this, the study considers how political ideas were received and understood by listeners. This work also adds to a growing field of scholarship that goes beyond examining the institutional histories of Germany’s broadcasters and analyzes how German broadcasters influenced society itself. -

Brandon Moreno Naranjeros Ganan Sorprendió Al Mundo De Las MMA Con Su Combate Ante Deiveson Y Mandan De Nuevo Figueiredo

Expreso Comparte las noticias en Facebook Expresoweb Miércoles 23 de Diciembre de 2020 Síguenos en Twitter @Expresoweb / Instagram @Expresomx FUTBOL AL FIN GANARON FUERA DE CASA Los Tigres tuvieron 4 oportunida- Diego Rossi, quien encontró un des para ganar un título internacio- balón al área en triuangulación con nal, pero éste no llegaba para los Carlos Vela y Mark-Anthony Kaye regios hasta este martes, cuando y definió de vaselina. le dieron la vuelta al marcador al La remontada inició a los 72 de LAFC de Carlos Vela para festejar tiempo corrido con gol de Hugo el título de la Liga de Campeones Ayala en un remate de cabeza en de Concacaf. tiro de esquina, a lo que se sumó Los Tigres habían perdido finales André-Pierre Gignac con tanto de Concacaf en 2016, 2017 y 2019, desde fuera del área a los 84 mi- además de la Copa Libertadores nutos de juego para completar el ante River Plate en 2015, y los títu- triunfo de los universitarios en la los internacionales se les negaron, burbuja de Orlando. pero un gol del de siempre, su ídolo, Con este triunfo, los Tigres se André-Pierre Gignac significó la clasificaron a la Copa Mundial de diferencia. Clubes que se disputará del 1 al Después de un primer tiempo sin 11 de febrero en Doha, Catar, con muchas opciones, guardaron las el Bayern Munich (UEFA), Ulsan emociones para la parte comple- Hyundai (Asia), Auckland City mentaria, e incluso el LAFC se pu- (Oceanía), Al-Ahly (África) y el so adelante con gol del uruguayo anfitrión Al-Duhail como los cla- Mira las galerías de fotos de este cuaderno en expreso.com.mx/accion.html Hoy edita esta sección Víctor López Mazón CCIÓN ¿Tienes algo que comentar? [email protected] ESPECIAL/EXPRESO LIGA MEXICANA DEL PACÍFICO Brandon Moreno Naranjeros ganan sorprendió al mundo de las MMA con su combate ante Deiveson y mandan de nuevo Figueiredo. -

2021 UFC Prizm Checklist

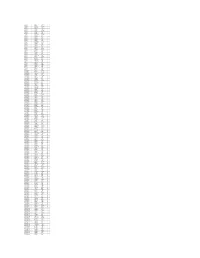

2021 Prizm UFC Checklist - By Subject 212 Subjects; 70 with Autographs Fighter Set Card # Team Al Iaquinta Auto - Octagon Signatures 3 Lightweight Al Iaquinta Auto - Sensational Signatures 13 Lightweight Al Iaquinta Base - Horizontal 102 Lightweight Aleksandar Rakic Base - Vertical 16 Light Heavyweight Alex Caceres Base - Horizontal 112 Featherweight Alex Perez Base - Vertical 26 Flyweight Alexander Gustafsson Auto - Signatures 20 Heavyweight Alexander Gustafsson Base - Horizontal 122 Light Heavyweight Alexander Volkanovski Base - Vertical 36 Featherweight Alexander Volkanovski Insert - Color Blast SSP 16 Featherweight Alexander Volkanovski Insert - Fearless 17 Featherweight Alexander Volkanovski Insert - Fireworks 11 Featherweight Alexander Volkanovski Insert - Instant Impact 25 Featherweight Alexander Volkov Base - Horizontal 132 Heavyweight Alexandre Pantoja Base - Vertical 46 Flyweight Alexis Davis Base - Horizontal 142 Flyweight Alistair Overeem Auto - Sensational Signatures 1 Heavyweight Alistair Overeem Base - Vertical 56 Heavyweight Alistair Overeem Insert - Knockout Artists 10 Heavyweight Aljamain Sterling Base - Horizontal 152 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Auto - Champion Signatures 6 Featherweight Amanda Nunes Base - Vertical 66 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Color Blast SSP 6 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Fearless 16 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Fireworks 23 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Instant Impact 24 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Knockout Artists 11 Bantamweight Amanda Ribas Base - Horizontal 162 -

2021-Panini-Prizm-UFC-Checklist

Base Horizontal 101 Jon Jones Light Heavyweight Base Horizontal 102 Al Iaquinta Lightweight Base Horizontal 103 Lina Lansberg Bantamweight Base Horizontal 104 Aspen Ladd Bantamweight Base Horizontal 105 Misha Cirkunov Light Heavyweight Base Horizontal 106 Cody Garbrandt Bantamweight Base Horizontal 107 Rodolfo Vieira Middleweight Base Horizontal 108 Dominick Reyes Light Heavyweight Base Horizontal 109 Matt Schnell Flyweight Base Horizontal 110 Ian Heinisch Middleweight Base Horizontal 111 Jose Aldo Bantamweight Base Horizontal 112 Alex Caceres Featherweight Base Horizontal 113 Luke Rockhold Light Heavyweight Base Horizontal 114 Kron Gracie Featherweight Base Horizontal 115 Nate Diaz Welterweight Base Horizontal 116 Colby Covington Welterweight Base Horizontal 117 Roosevelt Roberts Lightweight Base Horizontal 118 Brad Riddell Lightweight Base Horizontal 119 Tony Ferguson Lightweight Base Horizontal 120 Israel Adesanya Middleweight Base Horizontal 121 Josh Emmett Featherweight Base Horizontal 122 Alexander Gustafsson Light Heavyweight Base Horizontal 123 Magomed Ankalaev Light Heavyweight Base Horizontal 124 Brad Tavares Middleweight Base Horizontal 125 Neil Magny Welterweight Base Horizontal 126 Cory Sandhagen Bantamweight Base Horizontal 127 Roxanne Modafferi Flyweight Base Horizontal 128 Dustin Poirier Lightweight Base Horizontal 129 Uriah Hall Middleweight Base Horizontal 130 Jair Rozenstruik Heavyweight Base Horizontal 131 Junior Dos Santos Heavyweight Base Horizontal 132 Alexander Volkov Heavyweight Base Horizontal 133 Marion Reneau -

Brandon Moreno Naranjeros Ganan Sorprendió Al Mundo De Las MMA Con Su Combate Ante Deiveson Y Mandan De Nuevo Figueiredo

Expreso Comparte las noticias en Facebook Expresoweb Miércoles 23 de Diciembre de 2020 Síguenos en Twitter @Expresoweb / Instagram @Expresomx FUTBOL AL FIN GANARON FUERA DE CASA Los Tigres tuvieron 4 oportunida- Diego Rossi, quien encontró un des para ganar un título internacio- balón al área en triuangulación con nal, pero éste no llegaba para los Carlos Vela y Mark-Anthony Kaye regios hasta este martes, cuando y definió de vaselina. le dieron la vuelta al marcador al La remontada inició a los 72 de LAFC de Carlos Vela para festejar tiempo corrido con gol de Hugo el título de la Liga de Campeones Ayala en un remate de cabeza en de Concacaf. tiro de esquina, a lo que se sumó Los Tigres habían perdido finales André-Pierre Gignac con tanto de Concacaf en 2016, 2017 y 2019, desde fuera del área a los 84 mi- además de la Copa Libertadores nutos de juego para completar el ante River Plate en 2015, y los títu- triunfo de los universitarios en la los internacionales se les negaron, burbuja de Orlando. pero un gol del de siempre, su ídolo, Con este triunfo, los Tigres se André-Pierre Gignac significó la clasificaron a la Copa Mundial de diferencia. Clubes que se disputará del 1 al Después de un primer tiempo sin 11 de febrero en Doha, Catar, con muchas opciones, guardaron las el Bayern Munich (UEFA), Ulsan emociones para la parte comple- Hyundai (Asia), Auckland City mentaria, e incluso el LAFC se pu- (Oceanía), Al-Ahly (África) y el so adelante con gol del uruguayo anfitrión Al-Duhail como los cla- Mira las galerías de fotos de este cuaderno en expreso.com.mx/accion.html Hoy edita esta sección Víctor López Mazón CCIÓN ¿Tienes algo que comentar? [email protected] ESPECIAL/EXPRESO LIGA MEXICANA DEL PACÍFICO Brandon Moreno Naranjeros ganan sorprendió al mundo de las MMA con su combate ante Deiveson y mandan de nuevo Figueiredo. -

2021 Prizm UFC Checklist

2021 Prizm UFC Checklist - By Weight Class Weight Clases Split Between Men (9) and Women (3) Women's UFC Checklist Fighter Set Card # Team Holly Holm Auto - Signatures 5 Bantamweight Marlon Moraes Auto - Sensational Signatures 9 Bantamweight Miesha Tate Auto - Octagon Signatures 7 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Base - Vertical 66 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Color Blast SSP 6 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Fearless 16 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Fireworks 23 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Instant Impact 24 Bantamweight Amanda Nunes Insert - Knockout Artists 11 Bantamweight Aspen Ladd Base - Horizontal 104 Bantamweight Holly Holm Base - Vertical 4 Bantamweight Holly Holm Insert - Knockout Artists 1 Bantamweight Irene Aldana Base - Vertical 14 Bantamweight Julianna Pena Base - Vertical 45 Bantamweight Ketlen Vieira Base - Vertical 85 Bantamweight Lina Lansberg Base - Horizontal 103 Bantamweight Macy Chiasson Base - Vertical 37 Bantamweight Marion Reneau Base - Horizontal 133 Bantamweight Marlon Moraes Base - Vertical 57 Bantamweight Raquel Pennington Base - Horizontal 185 Bantamweight Sara McMann Base - Horizontal 147 Bantamweight Sijara Eubanks Base - Horizontal 157 Bantamweight Yana Kunitskaya Base - Vertical 83 Bantamweight GroupBreakChecklists.com 2021 Prizm UFC Checklist Fighter Set Card # Team Amanda Nunes Auto - Champion Signatures 6 Featherweight GroupBreakChecklists.com 2021 Prizm UFC Checklist Fighter Set Card # Team Jessica Andrade Auto - Octagon Signatures 15 Flyweight Jessica Andrade Auto - Sensational Signatures