Zephaniah: Plagiarist Or Skilled Orator ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zephaniah 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Zephaniah 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from the name of its writer. "Zephaniah" means "Yahweh Hides [or Has Hidden]," "Hidden in Yahweh," "Yahweh's Watchman," or "Yahweh Treasured." The uncertainty arises over the etymology of the prophet's name, which scholars dispute. I prefer "Hidden by Yahweh."1 Zephaniah was the great-great-grandson of Hezekiah (1:1), evidently King Hezekiah of Judah. This is not at all certain, but I believe it is likely. Only two other Hezekiahs appear on the pages of the Old Testament, and they both lived in the postexilic period. The Chronicler mentioned one of these (1 Chron. 3:23), and the writers of Ezra and Nehemiah mentioned the other (Ezra 2:16; Neh. 7:21). If Zephaniah was indeed a descendant of the king, this would make him the writing prophet with the most royal blood in his veins, except for David and Solomon. Apart from the names of his immediate forefathers, we know nothing more about him for sure, though it seems fairly certain where he lived. His references to Judah and Jerusalem (1:10-11) seem to indicate that he lived in Jerusalem, which would fit a king's descendant.2 1Cf. Ronald B. Allen, A Shelter in the Fury, p. 20. 2See Vern S. Poythress, "Dispensing with Merely Human Meaning: Gains and Losses from Focusing on the Human Author, Illustrated by Zephaniah 1:2-3," Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 57:3 (September 2014):481-99. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. -

Our God Is an Awesome God Ezekiel 1:1-28 Pastor Andrew Neville 15/11

Our God is an Awesome God Ezekiel 1:1-28 Pastor Andrew Neville 15/11/20 Sermon Summary God is worthy of all the praise we could ever give. That is the reason for the short, focused study of Ezekiel’s incredible vision from today’s sermon. Two weeks ago, we studied Habakkuk. A man who battled doubt and fear, yet he was transformed into a man who could face the future, by trusting God. Zephaniah (last week’s study), known as the Fierce Prophet, foretold a fearful judgment coming to Judah, but, that those who turn to God will be saved – and God will delight in them. Ezekiel was a contemporary of both Habakkuk and Zephaniah. While Ezekiel has 48 chapters devoted to his utterances, only chapter 1 was discussed today. Judah’s woes, at the hands of Babylonia, occurred over a period of 20 years. The first invasion in 605 BC saw Daniel and friends carted off to Babylon. In 597 BC, the Babylonians took 10,000 including Ezekiel to Babylon, to a place west of Babylon by the Kebar River. [The Iraqi city of Kabala, contains the burial remains of Ezekiel. The Kebar River may be another name for the Euphrates River or a tributary of it. P.] The final invasion – and total destruction and diaspora – of Jerusalem occurred in 586 BC. Only a remnant of the poor was left behind to forage an existence from the surrounding countryside. Ezekiel states he was 30 years of age (Ez. 1:1), which was the commencement age for a male going into the priesthood. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

The Chronology of the Events in Zechariah 12-14

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Honors Theses Undergraduate Research 3-28-2016 The Chronology of the Events in Zechariah 12-14 Won Jin Jeon Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jeon, Won Jin, "The Chronology of the Events in Zechariah 12-14" (2016). Honors Theses. 134. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors/134 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT J. N. Andrews Honors Thesis Andrews University College of Arts & Sciences Title: THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE EVENTS IN ZECHARIAH 12-14 Author’s Name: Won Jin Jeon Advisor: Rahel Schafer, PhD Completion Date: March 2016 In current scholarship, there is a lack of consensus on the timing of the specific events in Zechariah 12-14, with a focus on eschatological or sequential chronologies. Preliminary exegetical research has revealed many connections between the three chapters. For instance, the occurs 17 times (versus four times in the rest of Zechariah). This (ביום־ההוא) ”phrase “in that day concentrated usage closely interconnects the three chapters and suggests that the timeliness of all of the events is in close succession. -

Highlights from the Books of Zephaniah & Haggai

Highlights from the Books of Zephaniah & Haggai Treasures from God’s Word WT Library References Index Index Source Material ............................................................................... 5 Special Note .............................................................................................. 5 An Introduction to the Book of Zephaniah ................................... 6 Summary of the Highlights of the Book of Zephaniah ................ 7 Jehovah’s day of judgment is near ......................................................... 7 Punishment for Judah’s neighbors and more distant Ethiopia and Assyria ....................................................................................................... 7 Jerusalem’s rebellion and corruption ..................................................... 7 The outpouring of Jehovah’s anger and the restoration of a remnant . 7 Zephaniah – Outline of Contents .................................................. 8 Why Beneficial ................................................................................ 8 An Introduction to the Book of Haggai ....................................... 10 Summary of the Highlights of the Book of Haggai .................... 11 Message to people living in paneled houses, while Jehovah’s house lies in ruins .............................................................................................. 11 Proclamation that Jehovah will fill his house with glory ..................... 11 People are shown that neglect of temple rebuilding has made them -

A Literary Look at Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah

Grace Theological Journal 11.1 (1991) 17-27. [Copyright © 1991 Grace Theological Seminary; cited with permission; digitally prepared for use at Gordon and Grace Colleges and elsewhere] A LITERARY LOOK AT NAHUM, HABAKKUK, AND ZEPHANIAH RICHARD PATTERSON Although the stool of proper biblical exegesis must rest evenly upon the four legs of grammar, history, theology, and literary analysis, too often the literary leg receives such short fashioning that the resulting hermeneutical product is left unbalanced. While in no way minimizing the crucial importance of all four areas of exegesis, this paper con- centrates on the benefits of applying sound literary methods to the study of three often neglected seventh century B. C. prophetical books. Thorough literary analysis demonstrates that, contrary to some critical opinions, all three books display a carefully designed structure that argues strongly for the unity and authorial integrity of all the material involved. Likewise, the application of literary techniques can prove to be an aid in clarifying difficult exegetical cruces. * * * THE time has passed when evangelicals need to be convinced that the application of sound literary methods is a basic ingredient for proper biblical exegesis. A steady stream of papers, articles, and books attests to a growing consensus among evangelicals as to the essential importance of literary studies in gaining full insight into God's revela- tion.1 This paper presents some observations drawn from the study of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah in preparation for a forthcoming volume in Moody's Wycliffe Exegetical Commentary series (WEC). 1 Among recent books giving attention to literary analysis may be cited: Gordon D. -

Zephaniah Haggai Zechariah Malachi

ThroughThrough TheThe BibleBible SessionSession 3131 TheThe MinorMinor ProphetsProphets ZephaniahZephaniah // HaggaiHaggai ZechariahZechariah // MalachiMalachi From the miracle of our origin to the mystery of our destiny Timeline of the Minor Prophets Walls 445 B.C. Temple Rebuilt 518 B.C. Fall of Jerusalem 587 B.C. Fall of Samaria 722 B.C. First siege of Jerusalem 606 B.C. 800 750 700 650 600 550 500 450 Timeline of the Minor Prophets Walls 445 B.C. Temple Rebuilt 518 B.C. Fall of Jerusalem 587 B.C. Fall of Samaria 722 B.C. First siege of Jerusalem 606 B.C. 800 750 700 650 600 550 500 450 Hosea – The loving Prophet – Israel‟s call to repent and return Joel – The Day of the LORD – Earliest of the writing prophets Amos – The Shepherd Prophet – Judgment of the nations Obadiah – The judgment on Edom Jonah – Mercy for repentant Gentiles declared by one risen Micah – The LORD is coming to rule Nahum – The judgment of Nineveh Habakkuk – The just shall live by faith Zephaniah – Last of the pre-exile prophets - The coming judgment The Book of Zephaniah Zephaniah • Written during the reign of Josiah – c.640 B.C. - 609 B.C. • Last of the pre-exile prophets • His name means “Jehovah hides” – i.e., “protects” or “treasures.” • 17x “I will” statements of the LORD • Key phrase: “the day of the LORD” 7x • Thus we see his prophesies span history, speaking to the then current situation in Israel…(the sin of Israel & judgment on it‟s neighbours) • …but also speaking with clarity into our days Zephaniah • Zephaniah was the great grandson of king Hezakiah, so a distant cousin of Josiah – He traces his genealogy back through four generations to king Hezakiah (Ch1 v1). -

Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi

A People of the Book 8-Year Curriculum Year 6, Quarter 4 A Study of Selected Texts from Minor Prophets III (Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi) Mike White Minor Prophets III 4th Quarter 2012 Table of Contents =============================================================== Introduction Timeline Summary Table for all the Minor Prophets Lesson 1–Zephaniah 1-2:3- Urgency for national spiritual revival -7 October Lesson 2–Zephaniah 2:4-3–God’s present judgment & future hope-14 October Lesson 3-Haggai 1-Putting first things first-21 October Lesson 4-Haggai 2-Victory comes from the Lord & not from men!-28 October Lesson 5-Zechariah 1-3-Be encouraged because God is among us-4 November Lesson 6-Zechariah 4-6-Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit-11 November Lesson 7 –Zechariah 7-8-What does true religion look like?-18 November Lesson 8 –Zechariah 9-11-1st Oracle: Sovereignty of God and the Good Shepherd -25 November Lesson 9 – Zechariah 12-14-2nd Oracle: Our Lord’s final victory-2 December Lesson 10 –Malachi 1 – Cheating God? – 9 December Lesson 11 – Malachi 2 – Honoring God – 16 December Lesson 12 –Malachi 3-4-God is in control & Jesus Christ is on the way-23 December Lesson 13 – Pop Quiz-30 December Minor Prophets III 4th Quarter 2012 Introduction Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi Welcome to our study of the last four books of the Old Testament. All of what we study in these books will be perfectly applicable to our lives today because the stress and challenges of the Jews in Jerusalem during the time of Zephaniah, and the small group of Jews who returned to Judah and Jerusalem after the destruction of their way of life as foreordained by God demand the same level of trust toward God and obedience to His will today as it did 2500 years ago. -

Year 1 Unit 18 Zephaniah Nahum Habakkuk Nahum Nineveh 612

CROSSWAYS Year 1 Unit 18 Zephaniah Nahum Habakkuk Nahum Nineveh 612 Habakkuk Question of Theodicy Challenge to the Deuteronomist Jeremiah Review 1. Jeremiah’s excuse at his call? 2. Was he upper or lower class? 3. Supporter of Jerusalem’s priests? 4. What kings ruled during his ministry? 5. Why was he considered a traitor? 6. How is his message different from Isaiah? 7. Name a “symbolic action” in his preaching. 8. What are Jeremiah’s confessions? 9. Where do you find, “I will make a new covenant with Israel and Judah…”? 10. What year did Jerusalem fall? 11. What country conquered Judah? 12. Where did Jeremiah go after fall? Zephaniah 1. “Day of the Lord” is doom for Jerusalem 2. Reasons for Judgement 3. Call to Repentance 4. “Remnant” is saved 5. Restoration Kings of Judah before Exile Jehoiachin 598-97 Jehoahaz 609 BC Jehoiakim 609-598 Zedekiah 597-587 Josiah 640-609 BC BC (Coniah, (Shallum) BC (Eliakim) Jeconiah) BC (Mattaniah) • king at age 8 after • son of Josiah • Son of Josiah • Son of Jehoiakim • Son of Josiah, father Amon's selected as king • Placed on throne • Became king just uncle of assassination by people by Neco in time for siege Jehoiachin • Josiah's reform • taken by Neco to • Served Babylon • Taken to Babylon, • killed at Megiddo Egypt where he after Carchemish released from • Vassal to Babylon by Pharoah Neco died • Rebelled against prison 560 BC until rebelled Babylon but died before siege • Caught fleeing city after Jerusalem captured • Sons killed, eyes put out, died in prison in Babylon PREVIOUS SLIDES Themes in Jeremiah ■ Call (similar to other prophets) ■ Anti-clerical ■ Symbolic Actions ■ Jeremiah’s “Confessions” ■ Hope Oracles Jeremiah—An Overview Chapters 1-6 The reign of Josiah, 640-609, B.C. -

Notes on Zephaniah 2007 Edition Dr

Notes on Zephaniah 2007 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from the name of its writer. "Zephaniah" means "Yahweh hides [or has hidden]," "Yahweh's watchman," or "Yahweh treasured." The uncertainty arises over the etymology of the prophet's name, which scholars dispute. I prefer "Yahweh hides." Zephaniah was the great-great-grandson of Hezekiah (1:1), evidently King Hezekiah of Judah.1 If he was indeed a descendant of the king, this would make him the writing prophet with the most royal blood in his veins, except for David and Solomon. Apart from the names of his immediate forefathers we know nothing more about him for sure, though it seems fairly sure where he lived. His references to Judah and Jerusalem (1:10- 11) seem to indicate that he lived in Jerusalem, which would fit a king's descendant. UNITY Criticism of the unity of Zephaniah has not had great influence. Zephaniah's prediction of Nineveh's fall (2:15; 612 B.C.) led critics who do not believe that the prophets could predict the future to date the book after that event. Differences in language and style influenced some critics to divide the book up and identify its various parts with diverse sources. Yet the unity of the message and flow of the entire book, plus ancient belief in its unity, have convinced most conservative scholars to regard Zephaniah as the product of one writer.2 DATE Zephaniah ministered during the reign of King Josiah of Judah (640-609 B.C.; 1:1). -

2 Kings-Nahum-Jeremiah-Zephaniah

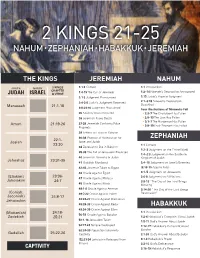

2 KINGS 21-25 NAHUM • ZEPHANIAH • HABAKKUK • JEREMIAH THE KINGS JEREMIAH NAHUM SOUTH NORTH 2 KINGS 1:1-3 Context 1:1 Introduction CHAPTER 1:4-19 The Call of Jeremiah 1:2–14 Nineveh’s Destruction Announced JUDAH ISRAEL & VERSE 2:1-3 Judgment Pronounced 1:15 Judah’s Hope in Judgment 2:1–3:19 Nineveh’s Destruction 2:4-3:6 Judah’s Judgment Deserved Manasseh 21:1-18 Described 3:6-24:10 Judgment Proclaimed Four Illustrations of Nineveh’s Fall 25 Seventy Years Predicted • 2:3–7 The Charioteer Has Fallen 26 Jeremiah Faces Death • 2:8–13 The Lion Has Fallen • 3:1–7 The Horseman Has Fallen 27-28 Jeremiah Confronts False Amon 21:19-26 • 3:8–19 Their Strength Has Failed Prophets 29 Letters to Exiles in Babylon 30-33 Promise of Restoration for ZEPHANIAH 22:1- Josiah Israel and Judah 23:30 1:1 Context 34 Zedekiah to Die in Babylon 1:2–3 Judgment on the Entire World 35-39 The Fall of Jerusalem Predicted 1:4–2:3 Judgment on the Southern 40 Jeremiah Remains in Judah Kingdom of Judah Jehoahaz 23:31-35 41 Gadaliah Murdered 2:4–15 Judgment on Israel’s Enemies 42-45 Jeremiah Taken to Egypt (2:13-15 Assyria Falls) 46 Oracle Against Egypt 3:1–5 Judgment on Jerusalem 23:36- 3:6-8 Judgment on All Nations (Eliakim) 47 Oracle Against Philistia Jehoiakim 24:7 3:9-13 “The Day of the Lord Brings 48 Oracle Against Moab Blessing” 49:1-6 Oracle Against Ammon 3:14-20 “The Day of the Lord Brings (Coniah, 49:7-22 Oracle Against Edom Restoration” Jeconiah) 24:8-17 Jehoiachin 49:23-27 Oracle Against Damascus 49:28-33 Oracle Against Kedar HABAKKUK 49:34-39 Oracle Against Elam (Mattaniah) 24:18- 1:1 Introduction 50-51 Oracle Against Babylon Zedekiah 25:21 1:2-4 Habakkuk’s Complaint About Judah 52:1-16 Jerusalem Taken 1:5-11 God’s Answer About Judah 52:17-23 Temple Destroyed 1:12-17 Habakkuk’s Complaint About 52:24-30 Population Taken into Babylon Gedaliah 25:22-26 Captivity 2:1-20 God’s Answer About Babylon (52:31-34 Jehoiachin Released From 3:1-2 Habakkuk’s Prayer Prison) 3:3-15 God’s Deliverance CAPTIVITY 3:16-19 Habakkuk’s Response. -

The Shepherd Imagery in Zechariah 9-141

404 O’Kennedy: The shepherd imagery OTE 22/2 (2009), 404-421 The shepherd imagery in Zechariah 9-141 D. F. O’KENNEDY (UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH) ABSTRACT The shepherd image emphasises the shepherd’s role as leader, pro- vider and protector. In Zechariah 1-8 one finds references to spe- cific leaders, for example king Darius, the high priest Joshua and the governor Zerubbabel. Zechariah 9-14 has no reference to a spe- cific leader. On the contrary, one finds 14 occurrences of the shep- herd image as a reference to God or earthly leaders (civil and re- ligious). The question posed by this article is: Which different per- spectives are portrayed by this image? The use of the shepherd im- age in Zechariah 9-14 cannot be restricted to one perspective or meaning like in some Biblical passages (cf. Ps 23). The following perspectives are discussed: God as the good shepherd (Zech 9:16; 10:3b, 8); the prophet as shepherd (11:4-14); the three bad shep- herds (11:8); the worthless shepherd, who deserts his flock (11:15- 17); God’s shepherd, his associate (13:7-9) and even a viewpoint that God is indirectly portrayed as an “uncaring shepherd” (cf. 11:4-17). A INTRODUCTION In Zechariah 1-8 one finds references to specific leaders like king Darius, the high priest Joshua and the governor Zerubbabel. However, Zechariah 9-14 has no reference to a specific leader. On the contrary, one finds 14 occurrences of the shepherd image2 as a reference to God or earthly leaders (civil and reli- gious).