Understanding Contemporary India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![123] CHENNAI, SATURDAY, MARCH 16, 2019 Panguni 2, Vilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2050 Part V—Section 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0422/123-chennai-saturday-march-16-2019-panguni-2-vilambi-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2050-part-v-section-4-80422.webp)

123] CHENNAI, SATURDAY, MARCH 16, 2019 Panguni 2, Vilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2050 Part V—Section 4

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14 GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2019 [Price: Rs. 44.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 123] CHENNAI, SATURDAY, MARCH 16, 2019 Panguni 2, Vilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2050 Part V—Section 4 Notifi cations by the Election Commission of India NOTIFICATIONS BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA ELECTION SYMBOLS (RESERVATION & ALLOTMENT) ORDER, 1968 No. SRO G-10/2019 The following Notifi cation of the Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110 001, dated 15th March, 2019 [24 Phalguna, 1940 (Saka)] is republished:- No. 56/2019/PPS-III:– WHEREAS, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notifi cation No. 56/2018/PPS-III, dated 13th April, 2018, as amended from time to time, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968; NOW, THEREFORE, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid notifi cation No. 56/2018/PPS-III, dated 13th April, 2018, as amended from time to time, published in the Gazette of India, Extra-Ordinary, Part-II, Section-3, Sub-Section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifi es: - (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognized political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. -

The Politics of Dalit Mobilization in Tamil Nadu, India

Litigation against political organization? The politics of Dalit mobilization in Tamil Nadu, India Article (Accepted Version) Carswell, Grace and De Neve, Geert (2015) Litigation against political organization? The politics of Dalit mobilization in Tamil Nadu, India. Development and Change, 46 (5). pp. 1106-1132. ISSN 0012-155X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/56843/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Litigation against Political Organization? The Politics of Dalit Mobilization in Tamil Nadu, India Grace Carswell and Geert De Neve ABSTRACT This article examines contemporary Dalit assertion in India through an ethnographic case study of a legal tool being mobilized by Tamil Nadu’s lowest-ranking Arunthathiyars in their struggle against caste-based offences. -

![296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7728/296-chennai-friday-october-1-2010-purattasi-15-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2041-407728.webp)

296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2010 [Price: Rs. 20.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041 Part V—Section 4 Notifications by the Election Commission of India. NOTIFICATIONS BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA ELECTION SYMBOLS (RESERVATION AND ALLOTMENT) ORDER, 1968 No. SRO G-33/2010. The following Notification of the Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110 001, dated 17th September, 2010 [26 Bhadrapada, 1932 (Saka)] is republished:— Whereas, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2009/P.S.II, dated 14th September, 2009, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, Now, therefore, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid Notification No. 56/2009/P.S.II, dated 14th September, 2009, as amended from time to time, published in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II—Section-3, sub-section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifies :— (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters ; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognised political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. -

Mapping out Fertility in South India : Methodology and Results Sébastien Oliveau

Mapping out fertility in South India : Methodology and results Sébastien Oliveau To cite this version: Sébastien Oliveau. Mapping out fertility in South India : Methodology and results. Guilmoto, C.Z., Rajan, S.I. Fertility transition in South India, SAGE, pp.90-113, 2005. halshs-00136809 HAL Id: halshs-00136809 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00136809 Submitted on 15 Mar 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mapping out fertility in South India: methodology and resultsi Sébastien Oliveau – UMR Géographie-cités [email protected] Recent progress made in Computer Aided Cartography (CAC) and in the Geographic Information System (GIS), supported by the power of computers, today warrants a consideration of the situation in space of statistical units and of their environment. Geographic databasesii containing several tens of thousands of units with which more than one hundred variables are linked can now be created. It therefore becomes possible – and necessary – to envision social change in India in its spatial dimension, and a study of fertility in South India will provide us with an eloquent example. In effect, the analytical cartographyiii of data concerning 70 000 villages comprising the five states and the union territory in the South calls for a new perception of fertility, freed of the a priori divisions constituting the administrative grid of taluks and districts. -

List of Life Members As on 20Th January 2021

LIST OF LIFE MEMBERS AS ON 20TH JANUARY 2021 10. Dr. SAURABH CHANDRA SAXENA(2154) ALIGARH S/O NAGESH CHANDRA SAXENA POST HARDNAGANJ 1. Dr. SAAD TAYYAB DIST ALIGARH 202 125 UP INTERDISCIPLINARY BIOTECHNOLOGY [email protected] UNIT, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 11. Dr. SHAGUFTA MOIN (1261) [email protected] DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY J. N. MEDICAL COLLEGE 2. Dr. HAMMAD AHMAD SHADAB G. G.(1454) ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 31 SECTOR OF GENETICS ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT. OF ZOOLOGY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 12. SHAIK NISAR ALI (3769) ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY FACULTY OF LIFE SCIENCE 3. Dr. INDU SAXENA (1838) ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH 202 002 HIG 30, ADA COLONY [email protected] AVANTEKA PHASE I RAMGHAT ROAD, ALIGARH 202 001 13. DR. MAHAMMAD REHAN AJMAL KHAN (4157) 4/570, Z-5, NOOR MANZIL COMPOUND 4. Dr. (MRS) KHUSHTAR ANWAR SALMAN(3332) DIDHPUR, CIVIL LINES DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY ALIGARH UP 202 002 JAWAHARLAL NEHRU MEDICAL COLLEGE [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 14. DR. HINA YOUNUS (4281) [email protected] INTERDISCIPLINARY BIOTECHNOLOGY UNIT ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 5. Dr. MOHAMMAD TABISH (2226) ALIGARH U.P. 202 002 DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY [email protected] FACULTY OF LIFE SCIENCES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 15. DR. IMTIYAZ YOUSUF (4355) ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT OF CHEMISTRY, [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH, UP 202002 6. Dr. MOHAMMAD AFZAL (1101) [email protected] DEPT. OF ZOOLOGY [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 ALLAHABAD 7. Dr. RIAZ AHMAD(1754) SECTION OF GENETICS 16. -

Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21St Century

Privilege in Dispute: Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21st Century John Harriss Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 44/2014 | September 2015 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 44/2015 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Harriss, John, Privilege in Dispute: Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21st Century, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 44/2015, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, September 2015. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright remains with the author. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Copyright for this issue: John Harriss, jharriss(at)sfu.ca. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Privilege in Dispute: Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu 3 Privilege in Dispute: Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21st Century Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

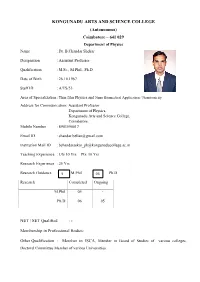

KONGUNADU ARTS and SCIENCE COLLEGE (Autonomous) Coimbatore – 641 029 Department of Physics Name : Dr

KONGUNADU ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE (Autonomous) Coimbatore – 641 029 Department of Physics Name : Dr. B.Chandar Shekar Designation : Assistant Professor Qualification : M.Sc., M.Phil., Ph.D Date of Birth : 26.10.1967 Staff ID : A/TS/53 Area of Specialization: Thin film Physics and Nano Biomedical Application / Nanotoxicity Address for Communication: Assistant Professor Department of Physics, Kongunadu Arts and Science College, Coimbatore. Mobile Number : 8903590017 Email ID : [email protected] Institution Mail ID : [email protected] Teaching Experience : UG 10 Yrs PG: 10 Yrs Research Experience : 25 Yrs Research Guidance : 5 M.Phil 06 Ph.D Research Completed Ongoing M.Phil 05 - Ph.D 06 05 NET / SET Qualified : - Membership in Professional Bodies: Other Qualification : Member in ISCA, Member in Board of Studies of various colleges, Doctoral Committee Member of various Universities. NATIONAL AWARDS Dr.ABDUL KALAM LIFE TIME ACHIEVEMENT NATIONAL AWARD -2017 by IRDP, India for the outstanding excellence and remarkable achievements in the field of TEACHING, RESEARCH & PUBLICATIONS. Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam Award for Scientific Excellence – 2017 by MARINA LABS, Research and Development, India for the outstanding research contribution. Selected for National Award of Excellence-2017 by Glacier journal research foundation, Global Management Council, Ahmedabad, India, for the outstanding contribution to research. Selected for Bharat Ratna Indra Gandhi Gold Medal Award 2017 for the outstanding contribution to Research, Education and Social Service by Global Economic Progress Research Foundation, India. The NEAR National Research Award-2014 (Senior category - Physical and Nanosciences), The NEAR Foundation, India, for the outstanding research contribution. Dr. Radhakrishna Shikshana Ratna National Award-2014 for distinguished contributions to the development of the nation and achieving outstanding excellence in the field of Teaching, Research and Publications by the International Institute for Social and Economic Reforms, Bangalore, India. -

Diversity of Ant Species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Campus of Kongunadu Arts and Science College, Coimbatore District, Tamil Nadu

© IJCIRAS | ISSN (O) - 2581-5334 February 2019 | Vol. 1 Issue. 9 DIVERSITY OF ANT SPECIES (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN THE CAMPUS OF KONGUNADU ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE, COIMBATORE DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU 1 2 3 Sornapriya j , m.phil scholar, Narmadha.n , m.phil scholar and dr. m. lakshmanaswami Department of Zoology, Kongunadu College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. Wayanad region of the Western Ghats. Bharti and Abstract Sharma [6] carried preliminary investigations on The study examined the diversity of ants in the, diversity and abundance of ants along an elevational Kongu nadu arts and science college campus, gradient in Jammu-Kashmir Himalaya. The food of ants Coimbatore District, Tamil Nadu, as there is no consists of insects, terrestrial arthropods, excretion from adequate information pertaining on ant diversity of plants, honey dew excreted by aphids and mealy bugs, this region. The present study was carried out during secretion of the caterpillars of the family Lycaenidae, October 2018 to December 2018. We have sampled seeds of plants etc [1]. ants by employing intensive all out search method. Ants are ubiquitous in distribution and occupy almost all The sampled specimens representing 10 species terrestrial ecosystems. There are about 15000 species of belonged to 5 genera and three subfamilies. The ants (7); only 11,769 species have been described (8). most diverse subfamily was Formicinae (2 genera The family Formicidae contains 21 subfamilies, 283 with 3 species), followed by Myrmicinae (2 genera genera and about 15000 living ant species of which 633 with 5 species), followed by Dolichoderinae (1 ant species belonging to 82 genera, 13 subfamilies are genera with 2 species). -

History 2016

GOVERNMENT ARTS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), KARUR – 639 005 M.A., HISTORY COURSE STRUCTURE UNDER CBCS SYSTEM (For the candidates admitted from the year 2016-2017 onwards) L COURSE SUBJECT TITLE MARKS WEEK TOTA CREDIT SEMESTER EXAM HOURS INSTR. HOURS SUBJECT CODE INT ESE Core Course – I History of India - I (Upto 1206 CE) P16HI1C1 6 5 3 25 75 100 Core Course – II History of Tamil Nadu - I (Upto 1565 CE) P16HI1C2 6 4 3 25 75 100 Core Course - III History of Europe - I (476 CE – 1453 CE) P16HI1C3 6 4 3 25 75 100 I Principles and Methods of Indian Core Course – IV P16HI1C4 6 5 3 25 75 100 Archaeology Elective Course - I General Knowledge and Current Affairs P16HI1E1 6 4 3 25 75 100 30 22 500 History of India – II (1206 CE – 1707 Core Course – V P16HI2C5 6 4 3 25 75 100 CE) History of Tamil Nadu - II (1565 CE – Core Course – VI P16HI2C6 6 4 3 25 75 100 2000 CE) II Core Course – VII History of World Revolutions P16HI2C7 6 5 3 25 75 100 Core Course – VIII Indian Administration P16HI2C8 6 5 3 25 75 100 Elective Course – II Journalism P16HI2E2 6 4 3 25 75 100 30 22 500 Core Course – IX History of India - III (1707 CE – 1947 CE) P16HI3C9 6 5 3 25 75 100 Core Course - X History of Far East P16HI3C10 6 5 3 25 75 100 Core Course – XI International Relations Since 1945 CE P16HI3C11 6 5 3 25 75 100 III Core Course - XII Historiography P16HI3C12 6 4 3 25 75 100 Elective Course – III Art and Architecture of India P16HI3E3 6 4 3 25 75 100 30 23 500 Core Course – XIII Contemporary India Since 1947 P16HI4C13 6 5 3 25 75 100 Core Course – XIV History of Kongu Nadu P16HI4C14 6 5 3 25 75 100 Elective Course – IV Human Rights P16HI4E4 6 4 3 25 75 100 IV Elective Course – V General Essay P16HI4E5 6 4 3 25 75 100 Project Work Project Work P16HI4PW 6 5 3 ** ** 100 30 23 500 TOTAL 120 90 2000 ** Dissertation – 80 Marks and Viva Voce Examinations – 20 Marks CHAIRMAN BOARD OF STUDIES IN HISTORY CONTROLLER OF EXAMINATIONS 1 Sl. -

Mizoram Gazette

The Mizoram Gazette. EXTRA. ORDINARY Published by Authoritv . REGN. NO. NE-313 (MZ) Vol. XXXI Aizawl, Wedilesday 13. 2. 2002, Magha 23, S.E. 1924, Issue No. 66 ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NOTIFICATION Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road New Delhi-llOOO! No. 56/2002/Jud-Il[ ·Dated: 10th January, 2002 1. WHEREAS, the Election Commission has decided to update its notification 56/2001/JudIII, dated 3rd April, 2001, specifying the names of recognised Na tional and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reserva tion and Allotment) Order, 1968, as amended from time to time. 2. NOW, THEREFORE, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order; 1968 and in supersession of its aforesaid principal notification No 56/2001/Jud III. dated 3id April, 2001, published in the Gazette of India. Extra Ordinary, Part-If, Section 3, Sub-Section (iii), and as amended from time to time the Election Commission hereby specifies. - (a) In Table L the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them; (b) In Table II, the State parties, the State or States in which they are State parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States; , (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognized political parties and postal address of their Headquarter, and (d) In Table IV. the free Symbols Ex- 66/2002 2 TABLE -I NATIONAL pARTIES --.----------_._-_..-------------.--_._---._-------------_._-_._----- S1. National Parties Symbol reserved Address No. -

The Orissa G a Z E T T E

Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments The Orissa G a z e t t e EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 528 CUTTACK, TUESDAY, APRIL 18, 2006 / CHAITRA 28, 1928 HOME (ELECTIONS) DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 28th March 2006 No. 1598—VE(A)-3/2006-Elec.—The following Notification dated the 6th March 2006 published by the Election Commission of India, New Delhi in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part - II, Section 3, sub-section (iii) is hereby republished for general information. By order ALKA PANDA Chief Electoral Officer & Ex officio Commissioner-cum-Secretary to Government ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NIRVACHAN SADAN, ASHOKA ROAD, NEW DELHI-110001 Dated the 6th March 2006 15 Phalguna, 1927 (Saka) NOTIFICATION NO. 56/2006-J. S. - III 1. WHEREAS, the Election Commission has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2005-Jud. - III., dated the 19th September 2005 specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968 as amended from time to time ; 2. NOW, THEREFORE, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968 as amended from time to time, and in supersession of its aforesaid Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments 2 principal Notification No. 56/2005-Jud. - III., dated the 19th September 2005 published in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part - II, Section 3, sub-section (iii), the Election Commission hereby specifies— (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them ; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States ; (c) In Table III, the registered unrecognized political parties and postal address of their Headquarters ; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. -

The Tribes of Palakkad, Kerala a Sociolinguistic Profile

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2015-028 The Tribes of Palakkad, Kerala A Sociolinguistic Profile Compiled by Bijumon Varghese The Tribes of Palakkad, Kerala A Sociolinguistic Profile Compiled by Bijumon Varghese SIL International® 2015 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2015-028, December 2015 © 2015 SIL International® All rights reserved Abstract This sociolinguistic survey of selected Scheduled Tribes in the Palakkad district of Kerala was sponsored and carried out under the auspices of the Indian Institute for Cross-Cultural Communication (IICCC), which is interested in sociolinguistic research and advocating mother tongue literature and literacy among minority people groups. The project started in December 2002 and fieldwork was finished by the end of March 2003. The report was written in August 2004. Researchers in addition to the author included Bijumon Varghese and Jose P. Mathew. This report tells about the unique social and linguistic features exhibited by the different tribes found in the Palakkad district. The broad purposes of this project were to investigate five areas: (1) investigate the speech varieties currently spoken among the tribes of Palakkad and their relationship with the languages of wider communication, Malayalam [mal], and neighbouring state language, Tamil [tam]; (2) assess the degree of variation within each speech variety of the Palakkad district; (3) evaluate the extent of bilingualism among minority language communities in Kerala’s state language, Malayalam; (4) investigate the patterns of language use, attitudes, and vitality; and (5) find out what materials are available about the tribal groups of the Palakkad district. The primary tribal languages observed were Irula [iru], Muduga [udg], Attapady Kurumba [pkr], Malasar [ymr], Mala Malasar [ima], Kadar [kej], and Eravallan [era].