Print Prince of Darkness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Article

VOL. CLVIII . No. 54,503 Arts &LEISURE SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 2008 Courtesy of LA Louver, Venice, Calif. “The Young” (2008), for which the artist, Enrique Martínez Celaya, mixed oil and wax on canvas — a technique he uses for many works. Layers of Devotion (and the Scars to Prove It) By JORI FINKEL SANTA MONICA, Calif. severed the tips of two fingers and the L.A. Louver gallery in Venice, MAGINE you’re an artist nearly cut your thumb to the bone. Calif., which opened on Thursday finishing work for a big gallery You’ve hit an artery. Blood is and runs through January 3. show. You’re standing on a spurting everywhere. To make matters worse, he had ladder trying to reach the top of a This is the scene that played out attached the chain-saw blade to a Iwooden sculpture with a chain saw; in June for the artist Enrique grinder for speed. the next thing you know, you’ve Martínez Celaya, when he was He credits his studio manager, sliced open your left hand. You’ve preparing for his first exhibition at Catherine Wallack, with thinking VOL. CLVIII . No. 54,503 THE NEW YORK TIMES, Arts& LEISURE SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 2008 as a physicist at the Brookhaven The other works in his Santa National Laboratory on Long Island. Monica studio that day, another Mr. Martínez Celaya is one of the sculpture and a dozen good-size rare contemporary artists who paintings now at L.A. Louver, are trained as a physicist. He studied also lessons in isolation — quantum electronics as a graduate sparse landscapes and astringent student at the University of snowscapes, boyish figures that California, Berkeley, until he found seem lost against the wide horizon, himself more and more often and animals holding their own, sneaking away to paint, something sometimes with no humans in sight. -

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA, B. 1964 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA, b. 1964 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND EDUCATION Provost Professor of Humanities and Arts, University of Southern California, 2017-present Roth Distinguished Visiting Scholar, Dartmouth College, 2016-2017 Montgomery Fellow, Dartmouth College, 2014-present Visiting Presidential Professor, University of Nebraska, 2007–2010 Associate Professor, Pomona College and Claremont Graduate University, 1994-2003 MFA, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1994 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, 1994 MS, University of California, Berkeley, 1988 BS, Cornell University, 1986 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2022 Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, The Grief of Almost, Hanover, New Hampshire Fisher Museum of Art, University of Southern California, SEA SKY LAND: towards a map of everything, Los Angeles, California Monterey Museum of Art, Enrique Martínez Celaya and Robinson Jeffers, Monterey, California Doheny Memorial Library, University of Southern California, Enrique Martínez Celaya and Robinson Jeffers, Los Angeles, California 2021 The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, There-bound, San Marino, California Galerie Judin, Enrique Martínez Celaya and Käthe Kollwitz: Von den ersten und den letzten Dingen (Of First and Last Things), Berlin, Germany Baldwin Gallery, A Third of the Night, Aspen, Colorado Galería Casado Santapau, Un poema a Madrid, Madrid, Spain 2019 Blain|Southern, The Mariner’s Meadow, London, United Kingdom 13th Havana Biennial, Detrás del Muro, Havana, Cuba Kohn Gallery, The Tears of Things, Los Angeles, California 2018 Galleri Andersson/Sandström, The Other Life, Stockholm, Sweden 2017 Jack Shainman Gallery, The Gypsy Camp, New York, New York Galerie Judin, The Mirroring Land, Berlin, Germany Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Nothing That Is Ours, Miami, Florida 2016 The Phillips Collection, One-on-One: Enrique Martínez Celaya/ Albert Pinkham Ryder, Washington, D.C. -

Enrique Martinez Celaya

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA Biography 1964 Born in Havana, Cuba Education 1994 Master of Fine Arts, Painting, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 1994 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME 1988 Master of Science, Quantum Electronics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 1986 Bachelor of Science, Applied & Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY Solo Exhibitions 2021 Enrique Martínez Celaya: A Third of the Night, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, 12 February - 14 March 2021 2020 Enrique Martínez Celaya: The Sword or the Road, Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art, Houston, TX, 18 January - 29 February 2020 2019 The Tears of Things, Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 13 September 2019 The Mariners Meadow, Blain Southern, London, UK, 23 May - 13 July 2019 The Boy: Witness and Marker 2003 - 2018, Robischon Gallery, Denver, CO 2018 The Other Life, Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden 2017 Nothing That Is Ours, Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami, FL The Mirroring Land, Galerie Judin, Berlin, Germany The Gypsy Camp, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Self and Sea, Parafin, London, United Kingdom, 19 May - 9 July 2016 (catalogue) Enrique Martínez Celaya: Small Paintings 1974-2015, Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, Birmingham, AL, 22 January - 19 March 2016 One-on-One: Enrique Martinez Celaya / Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. 2015 Enrique Martinez Celaya: Empires - Land, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, 10 September - 24 October 2015 Enrique Martínez Celaya, L.A. Louver, Venice, -

Print Layout 1

DECEMBER 2003 the art of living Sabina Wong-Sutch meets artist, former professor and mentor, Enrique Martínez Celaya, a successful and refreshingly human, tender and intelligent artist on a mission to remind us all of the priorities in life. Images courtesy of Enrique Martínez Celaya After artist Enrique Martínez Celaya decided to leave a as Martínez Celaya recalls, "We were so poor we all lived in promising career of quantum physics in the 1980s, he spent one room, and there was not even a bathtub." At age 12, the two years eking out a living by selling some of his paintings family relocated to Puerto Rico, his last stop before he would in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park. One day a passer-by move to America. In Puerto Rico, Martínez Celaya was asked to purchase not a painting, but his sketchbook, and apprenticed to the Spanish painter, Mayol, where he learned desperate for the money, Martínez Celaya had but little the classical methods of painting. Academically, he began to choice. A serendipitous meeting at a recent reception brought show his genius in physics and in the arts. "There was tur- the two together again. Martínez Celaya asked if he could moil in my life so I used art in pretty much the same way as buy his sketchbook back for "any sum of money" from this I use it now: how to understand things better. My work at the man. "Sorry," came the buyer's reply, he simply loved the time was very messy, and really reflected the ‘grossness’ of work and had come to develop a passionate affinity with it: my life at the time. -

Enrique Martinez Celaya

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA Born 1964, Cuba Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA Enrique Martínez Celaya is an artist, author, and former scientist whose work has been exhibited and collected by major institutions around the world, and he is the author of books and papers in art, poetry, philosophy, and physics. He has created projects and exhibitions for the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., and the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig, among many others, as well as for institutions customarily outside of the art world, including the Berliner Philharmonie, the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine in New York, and the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery in Berlin. Work by the artist is held in over 50 public collections internationally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig, and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford. He is the author of several books including, Collected Writings and Interviews 2010-2017, Collected Writings and Interviews 1990-2010, and The Nebraska Lectures, all published by the University of Nebraska Press (Lincoln), as well as, October, published by Cinubia Press (Amsterdam), On Art and Mindfulness: Notes from the Anderson Ranch, published by Whale & Star Press and the Anderson Ranch Arts Center (Los Angeles, Snowmass), as well as the artist book Guide, which was later serialized by the magazine Works & Conversations (Berkeley). His work has been the subject of several monographic publications including Enrique Martínez Celaya, 1992-2000 published by Wienand Verlag (Köln), Enrique Martínez Celaya: Working Methods published by Ediciones Polígrafa (Barcelona), and most recently Martínez Celaya, Work and Documents 1990-2015 published by Radius Books (Santa Fe). -

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA, B. 1964 ACADEMIC

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA, b. 1964 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND EDUCATION Provost Professor of Humanities and Arts, University of Southern California, 2017-present Roth Distinguished Visiting Scholar, Dartmouth College, 2016-2017 Montgomery Fellow, Dartmouth College, 2014-present Visiting Presidential Professor, University of Nebraska, 2007–2010 Associate Professor, Pomona College and Claremont Graduate University, 1994-2003 MFA, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1994 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, 1994 MS, University of California, Berkeley, 1988 BS, Cornell University, 1986 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Kohn Gallery, The Tears of Things, Los Angeles, California Blain|Southern, The Mariner’s Meadow, London, United Kingdom 13th Havana Biennial, Detrás del Muro, Havana, Cuba 2018 Galleri Andersson/Sandström, The Other Life, Stockholm, Sweden 2017 Jack Shainman Gallery, The Gypsy Camp, New York, New York Galerie Judin, The Mirroring Land, Berlin, Germany Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Nothing That Is Ours, Miami, Florida 2016 The Phillips Collection, One-on-One: Enrique Martínez Celaya/ Albert Pinkham Ryder, Washington, D.C. Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, Small Paintings: 1974- 2015, Birmingham, Alabama Parafin, Self and Sea, London, United Kingdom Baldwin Gallery, Self and Land, Aspen, Colorado 2015 Jack Shainman Gallery, Empires: Land and Empires: Sea, New York, New York L.A. Louver, Lonestar, Venice, California 2014 Hood Art Museum, Dartmouth College, Burning as It Were a Lamp, Hanover, New Hampshire Galleri Andersson/Sandström, A Wasted Journey, A Half-finished Blaze, Umeå, Sweden Parafin, The Seaman’s Crop, London, United Kingdom 2013 Strandverket Konsthall, The Tower of Snow, Marstrand, Sweden SITE Santa Fe, The Pearl, Santa Fe, New Mexico Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Burning as It Were a Lamp, Miami, Florida 2012 The State Hermitage Museum, The Tower of Snow, St. -

Jack Shainman Gallery

513 WEST 20TH STREET NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10011 TEL: 212.645.1701 FAX: 212.645.8316 JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA Born in 1964, Cuba Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA EDUCATION 1994 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME 1994 MFA, Painting, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 1988 MS, Quantum Electronics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 1986 BS, Applied & Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2020 – 2021 A9, Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami. FL, December 2, 2020 – January 16, 2021 2020 Enrique Martínez Celaya: The Sword or the Road, Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art, Houston, TX, January 18, – February 29, 2020. 2019 The Tears of Things, Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, September 13, 2019 – November 1, 2019. Havana Biennial 2019, Havana, Cuba, April 12 – May 12, 2019. A Cool Breeze, Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague, Czech Republic, January 30 – April 28, 2019. Enrique Martinez Celaya, The Huntington, San Marino, CA. 2017 WWW.JACKSHAINMAN.COM [email protected] Enrique Martinez Celaya: Selected BiOgraphy Page 2 Enrique Martinez Celaya: The Gypsy Camp, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, NY, March 16 – April 22, 2017. 2016 – 2017 One-On-One: Enrique Martínez Celaya / Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, October 13, 2016 – April 2, 2017. 2016 Enrique Martinez Celaya: Self and Sea, Parafin, London, United Kingdom, May 19 – June 9, 2016 Enrique Martinez Celaya: Self and Land, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, June 23 – July 24, 2016. Enrique Martínez Celaya: Small Paintings 1974-2015, Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, Birmingham, AL, January 22 – March 19, 2016. Enrique Martínez Celaya, Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, September 2016. -

Enrique Martínez Celaya a Wasted Journey, a Half-Finished Blaze

PRESS RELEASE: GALLERI ANDERSSON/SANDSTRÖM, UMEÅ Enrique Martínez Celaya A Wasted Journey, A Half-Finished Blaze Opening February 2nd, at 11-14 am. At 11.30 am U.S. Ambassador to Sweden, Mark Brzezinski will inaugurate the exhibition. Galleri Andersson/Sandström Umea is proud to present Umeå’s first exhibition of the work of the internationally renowned artist Enrique Martínez Celaya. An American-Cuban artist based in Miami, Martínez Celaya is represented in over 30 museum collections worldwide, including MOMA in New York, The State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The exhibition "A Wasted Journey, A Half-Finished Blaze" showcases five new paintings and an impressive sculptural installation that fills the gallery in Umedalen. The main sculpture in this environment presents a bronze boy encrusted with large jewels crying onto a bed of pine needles. Aktrisgränd 34 S-903 64 Umeå +46 90 14 49 90 www.gsa.se /[email protected] His tears carve a channel through the beds as they cascade from one bed to the next. When they reach the last bed, the merger stream falls on a stack of dishes and pots reminiscent of what one might find in the sink of any house. The stream of tears never stops. Martínez presents a metaphorical, mystical world which resists a narrative and is elusive and open to one’s own interpretation. Martínez Celaya’s work uses everyday imagery heavy with symbolism, such as the solitary human figure in the landscape, the beds, animals and trees, often in an environment covered with white snow. -

Print Layout 1

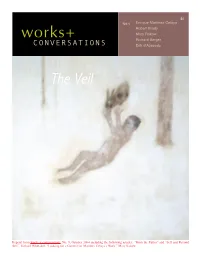

$8 N o 9 Enrique Martínez Celaya Robert Brady works+ Mary Rakow Richard Berger CONVERSATIONS Erik d’Azevedo The Veil Reprint from works + conversations, No. 9, October 2004 including the following articles: “From the Editor” and “Self and Beyond Self,” Richard Whittaker; “Looking for a Context for Martínez Celaya’s Work,” Mary Rakow “UNBROKEN POETRY (HERMAN MELVILLE)” 1999 OIL, TAR, AND FABRIC ON LINEN 96” X 96” FROM THE EDITOR claim be made that there is a difference between the The title of the painting on the cover The Veil authentic and the inauthentic. We are placed in the suggests a possible theme for issue #9. Exile was realm of being, which is where the work of Martínez considered because both Enrique Martínez Celaya Celaya is located. This is not the being of Aristotle, of and Erik d’Azevedo have experienced cultural eternal substance, but the realm of man’s being, the dislocation. But “exile” and “the veil” both imply ontological space of experience. separation; one of loss, home left behind, the other of If contemporary relativism is, as Martínez Celaya something covered over. Both provide points of puts it in Guide, “a drain through which all of the departure for many levels of consideration. possibilities of art eventually will vanish” - then what Martínez Celaya, born in Cuba, emigrated to Spain, could the antidote be? As I understand Martínez then to Puerto Rico and then to the United States. Celaya, it will not lie in religious dogma, metaphysics, In his own words, “Whether I’m in the United States science or pseudo-science. -

Object Oriented Ontology, Art and Art-Writing

After The Passions: Object Oriented Ontology, Art and Art-writing PRUE GIBSON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 2014 Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Signed: Dated: i Acknowledgements My supervisor Professor Stephen Muecke welcomed me into academic life and has supported me ever since. He introduced me to Speculative Realism and Object Oriented Ontology and slowed my usual cracking pace to a more considered and cautious speed. Each time I felt I had discovered something new about writing, I realised Stephen had led me there. I have often tried to emulate his mentoring method for my own students: without judgement, enthusiastic and twinkle-eyed. Through the second half of the thesis process, my co-supervisor Professor Edward Scheer jumped in and demanded evidence, structured argument and accountability. This was the perfect timing for a rigorous edit. -

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA B. 1964 EDUCATION

ENRIQUE MARTINEZ CELAYA b. 1964 EDUCATION & PROFESSORSHIPS Visiting Presidential Professor, University of Nebraska, 2007–2010 Associate Professor, Pomona College and Claremont Graduate University, 1994-2003 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, 1994 MFA, Painting, University of California, Santa Barbara, California, 1994 MS, Quantum Electronics, University of California, Berkeley, California, 1989 BS, Applied Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1986 SELECTED PROJECTS The State Hermitage Museum, The Tower of Snow, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012 LA Louver, Venice, California, 2012 Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden, 2012 Galeria Joan Prats, El Cielo de Invierno, Barcelona, Spain, 2012 The State Hermitage Museum, The Master, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012 Miami Art Museum, Schneebett, Miami, Florida, 2011 Simon Lee Gallery, The Open, London, United Kingdom, 2010 Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, The Crossing, New York, New York, 2010 Liverpool Street Gallery, The Lovely Season, Sydney, Australia, 2008 LA Louver, Daybreak, Venice, California, 2008 Miami Art Museum, Nomad, Miami, Florida, 2007 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Six Paintings on the Duration of Exile, Taura, Japan, 2007 Baldwin Gallery, Another Show for the Leopard, Aspen, Colorado, 2007 John Berggruen Gallery, For Two Martinson Poems, San Francisco, California, 2007 Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig, Schneebett, Leipzig, Germany, 2006 Sheldon Museum of Art, Coming Home, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2006 Oakland Museum of California, Works on Paper (1995-2005), -

Enrique Martínez Celaya Biography — Born 1964, Havana, Cuba Lives

Enrique Martínez Celaya Biography — Born 1964, Havana, Cuba Lives and works in Los Angeles Education and Professorships — 2014 Montgomery Fellow, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 2007-10 Visiting Presidential Professor, University of Nebraska 1994-2003 Associate Professor, Pomona College and Claremont Graduate University 1994 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine 1994 MFA, Painting, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 1988 MS, Quantum Electronics, University of California, Berkeley, California 1986 BS, Applied & Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Selected Solo Exhibitions — 2017 Galerie Judin, Berlin, Germany Jack Shainman Gallery, New York 2016 Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Parafin, London, United Kingdom 2015 Jack Shainman Gallery, New York LA Louver, Venice, California 2014 Parafin, London, United Kingdom Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Umeå, Sweden 2013 Strandverket Konsthall, Marstrand, Sweden SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico Fredric Snitze Gallery, Miami, Florida James Kelly Contemporary, Santa Fe, New Mexico 2012 The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia LA Louver, Venice, California Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden Galeria Joan Prats, Barcelona, Spain 2011 Miami Art Museum, Miami, Florida LA Louver Gallery, Venice, California Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney, Australia 2010 Simon Lee Gallery, London, United Kingdom Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York, New York Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, Colorado 2009 Akira Ikeda Gallery,