Responses to Alcohol-Related Problems in Four Western Countries: Characterising and Explaining Cultural Wetness and Dryness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Programs in Higher Education BRINGING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

Designing Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Programs in Higher Education BRINGING THEORY INTO PRACTICE U.S. Department of Education Designing Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Programs in Higher Education BRINGING THEORY INTO PRACTICE U.S. Department of Education Additional copies of this book can be obtained from: The Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Education Development Center, Inc. 55 Chapel Street Newton, Massachusetts 02158-1060 http://www.edc.org/hec/ 800-676-1730 Fax: 617-928-1537 Production Team: Kay Baker, Judith Maas, Anne McAuliffe, Suzi Wojdyslawski, Karen Zweig Published 1997 This publication was produced under contract no. SS95013001. Views expressed are those of the authors. No official support or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education is intended or should be inferred. ■ Contents A Social Role Negotiation Approach to Campus Prevention of Alcohol and Other Drug Problems by Thomas W. Blume • 1 The Web of Caring: An Approach to Accountability in Alcohol Policy by William David Burns and Margaret Klawunn • 49 An Integrated Theoretical Framework for Individual Responsibility and Institutional Leadership in Preventing Alcohol and Drug Abuse on the College Campus by Gerardo M. Gonzalez • 125 A Social Ecology Theory of Alcohol and Drug Use Prevention among College and University Students by William B. Hansen • 155 College Student Misperceptions of Alcohol and Other Drug Norms among Peers: Exploring Causes, Consequences, and Implications for Prevention Programs by H. Wesley Perkins •177 Institutional Factors Influencing the Success of Drug Abuse Education and Prevention Programs by Philip Salem and M. Lee Williams • 207 ■ Preface From Fiscal Year 1988 through Fiscal Year 1991 the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE) of the U.S. -

Alcohol Marketing and Advertising, a Report to Congress

Alcohol Marketing and Advertising A Report to Congress September 2003 Federal Trade Commission, 2003 Timothy J. Muris Chairman Mozelle W. Thompson Commissioner Orson Swindle Commissioner Thomas B. Leary Commissioner Pamela Jones Harbour Commissioner Report Contributors Janet M. Evans, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Jill F. Dash, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Neil Blickman, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Enforcement C. Lee Peeler, Deputy Director, Bureau of Consumer Protection Mary K. Engle, Associate Director, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Joseph Mulholland, Bureau of Economics Assistants Dawne E. Holz, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Office of Consumer and Business Education Michelle T. Meade, Law Clerk, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Chadwick Crutchfield, Intern, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Executive Summary The Conferees of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees directed the Federal Trade Commission to study the impact on underage consumers of ads for new flavored malt beverages, and whether the beverage alcohol industry has implemented the recommendations contained in the Commission’s 1999 report to Congress regarding alcohol industry self- regulation. This report sets forth the Commission’s findings on these subjects. The Commission’s investigation of flavored malt beverages (FMBs) indicates that adults appear to be the intended target of FMB marketing, and that the products have established a niche in the adult market. The investigation found no evidence of targeting underage consumers in the FMB market. FMB marketers placed advertisements in conformance with the industry standard that at least 50% of the advertisement’s audience consists of adults age 21 and over. -

Study of Proposed Amendments to Canada's Beer Standard of Identity

Study of Proposed Amendments to Canada’s Beer Standard of Identity Report prepared by Beer Canada’s Product Quality Committee October 2013 Authors Bill Andrews Ludwig Batista Manager, Brewing Quality National Technical Director Molson Coors Canada Sleeman Breweries Ltd. [email protected] [email protected] Ian Douglas (Committee Chair) Dr. Terry Dowhanick Global Director, Quality and Food Safety Quality Assurance and Product Integrity Manager Molson Coors Canada Labatt Breweries of Canada [email protected] [email protected] Anita Fuller Brad Hagan Quality Services Manager Director of Brewing Operations Great Western Brewing Company Labatt Breweries of Canada [email protected] [email protected] Peter Henneberry Dave Klaassen Adviser Vice President, Operations Moosehead Breweries Ltd. Sleeman Breweries Ltd. [email protected] [email protected] Russell Tabata Luke Harford Chief Operating Officer President Brick Brewing Co. Limited Beer Canada [email protected] [email protected] Luke Chapman Manager, Economic and Technical Affairs Beer Canada [email protected] 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 2.0 The Canadian Brewing Industry .............................................................................................................. 5 3.0 Historical Context of the Standard ......................................................................................................... -

Quick Report

Quick Report Average Quiz Score Total Responses Average Score Max Points Attainable Average Percentage Who was the first Prime Minister of Canada? 82 0.98 1 97.56% What is the most popular sport in Canada? 81 0.95 1 95.06% What two animals are featured on the Canadian Coat of Arms? 81 0.48 1 48.15% What is the largest City in Canada? 81 0.95 1 95.06% What is the national animal of Canada? 81 0.98 1 97.53% True or false- the origin of the name Canada is derived from the Huron-Iroquois word, Kanata, meaning a village or settlement? 81 0.96 1 96.30% What are french fries, gravy and cheese curds called? 81 0.99 1 98.77% Wood Buffalo National Park has the world's longest 81 0.79 1 79.01% What percentage of all the alcohol consumed in Canada is Beer? 80 0.50 1 50.00% How many countries are larger geographically than Canada? 80 0.65 1 65.00% What is the best selling beer in Canada? 77 0.21 1 20.78% What percentage of the world's fresh water is in Canada? 78 0.42 1 42.31% Who is the Head of State of Canada? 78 0.63 1 62.82% What was launched in 1936 to unify our sprawling Country? 77 0.38 1 37.66% True or False - Laura Secord warned the British of an impending attack on Canada by the Americans during the war of 1812 and because of this won t… 77 0.86 1 85.71% What is an Inukshuk? 77 0.95 1 94.81% 50% of the world's population of this animal live in Canada? 76 0.49 1 48.68% What is the most popular coffee chain in Canada? 76 0.97 1 97.37% What animal is on the Quarter? 76 0.64 1 64.47% What was the name of the system of safe passages and safe houses that allowed American slaves to escape to freedom in Canada? 76 0.87 1 86.84% Canada produces 80% of the world's supply of what? 75 0.77 1 77.33% What is slang for Canadian? 75 0.77 1 77.33% What is the most recent territory in Canada called? 75 0.92 1 92.00% Please enter in your contact information to be entered to win the Canada 150 prize packFirst name and phone # or email 68 0.00 0 0% Total: 82 16.38 23 71.21% Who was the first Prime Minister of Canada? Paul Martin John Diefenbaker John A. -

CAMRA Highlands & Western Isles

CAMRA Highlands & Western Isles Contains Full List of Highlands & Western Isles Real Ale Outlets “No Real Beer in Scotland” More beer choice arrives - Shock claim! in Inverness - Old and New Highland Breweries add new beers More awards for Highland breweries Order! Order! Our dis?-honourable members enjoy Highland beer In memory of John Aird elcome… to the Spring edition of our ne of the joys of enjoying real ale is the continual quarterly newsletter. In this edition: W O changes and developments that you find. > John Aird remembered The way that real beer develops over the days that it is > Updated Branch Diary > Socials, Tastings & Outings - Reports being served in one of our good pubs, the way that brew- > Awards news ers tweak and develop their beers so that you are contin- > Focus on - new Editor, Gordon Streets ually comparing and appreciating,. > Your Letters and E-mails Here in the Highlands, we are enjoying 2 new, local > Real Cider News breweries starting / increasing the beer they are produc- > Pub & Brewery News ing and selling. There is the news of another new brew- > Updated Real Ale Pubs list ery being established in the Elgin area, and yet another We welcome your letters, news, views and opinions. Let us know what is happening at your local, or tell us new brewery may be brewing this year in the Glen Ur- about pubs you have visited. quhart area. Thanks to all who have taken trouble to send in pub and beer reports, or articles, but especially to regulars Some of our bigger, established breweries are producing Eric, Gareth, Steve and Jack, who keep us up-to-date new beers and even more seasonal, experimental beers. -

Local Option Laws in Ontario Sacred Boundaries: Local Opi'ion Laws in Ontario

SACRED BOUNDARIES: LOCAL OPTION LAWS IN ONTARIO SACRED BOUNDARIES: LOCAL OPI'ION LAWS IN ONTARIO By. KATHY LENORE BROCK, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University September 1982 MASTER OF ARTS (1982) MCMASTER UNIVERSITY (Political Science) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Sacred Boundaries: Local Option Laws in Ontario AUTHOR: Kathy Lenore Brock, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor T.J. Lewis NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 162 ii Abstract The laws of Ontario operate on the principle that indivi duals should govern their own conduct unless it affects others adversely. The laws are created to protect individuals and their property and to ensure that citizens respect the rights of others. However, laws are protected and entrenched which defy this principle by permitting and fostering intolerance. This thesis addresses the local option laws of Ontario's liquor legislation which protect and legitimize invasion of personal liberty. These laws permit municipalities to prohi bit or restrict retail sale of liquor within their boundaries by vote or by COQ~cil decision. Local option has persisted t:b.roughout Ontario's history and is unlikely to be abolished despite the growing acceptance of liquor in society. To explain the longevity of these la.... ·ts, J.R. Gusfield' s approach to understanding moral crusades is used. Local option laws have become symbols of the status and influence of the so ber, industrious middleclass of the 1800's who founded Ontario. The right to control drinking reassures people vlho adhere to the traditional values that their views are respected in society. -

Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Medical Education. INSTITUTION State Univ

Doman RESUME ED 192 216 CG 014 672 AUTHOR Galanter, Marc. Ed. TITLE Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Medical Education. INSTITUTION State univ. of New York, Brooklyn., Downstate Medical Center.: Yeshiva univ.. Bronx, N.Y. Albert Einstein Coll. of Medicine. PONS AGENCY National Inst. on Drug Abuse (DBZW/PHS), Rockville, Md. REPORT NO ADM-79 -891 PUP EATS SO GRANT TO1-DA-00083: T01-CA-00197 NOTE 128p. AVAILABLE Pint superintendent of Documents, O.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 EDES PRICE mF01/FC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alcohol Education: *Drug Abuse: *Drug Education: Higher Education: *Medical Education: medical School Faculty; Medical Services; *Physician Patient Relationship: Physicians: *social Responsibility: State cf the Art Reviews ABSTRACT This book presents the state of the art of American medical education in alcohol and drug abuse,and is the culmination of a four-year collaborative effort among the medicalschool faculty, of the Career Teacher Program in Alcohol and DrugAbuse. The first part contains reports, curricula, andsurvey data prepared for the medical education community, focusingon drug abuse and alcoholism teaching in medical/osteopathic schools, icourse on alcoholism for physicians, the Career Teacher Program andResource Handbook, and the role of substance abuse attitudes in_treatment.The second part is-- the proceedings of the NationalConference on Medical Education and Drug Abuse, November 1977. The conference sessionsaddress issues such as: (1) the physician's role in substance abuse treatment;(2) physicians' use of drugs and alcohol:(3) drug abuse questions on the National Board Examinations: and (4)an overview of the Career Teacher Program activities. (Author/HLM) * *s * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** ***************** * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *0 Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original document. -

Prohibition, American Cultural Expansion, and the New Hegemony in the 1920S: an Interpretation

Prohibition, American Cultural Expansion, and the New Hegemony in the 1920s: An Interpretation IAN TYRRELL* In the [920s American prohibitionists, through the World League against Alcohol ism, sought to extend their war on liquor beyond the boundaries of the United States. Prohibitionistsfailed in their efforts due to anti-American sentiment, complex class and cultural opposition to prohibition, and negative reporting of the experi ment with prohibition in the U.S. Nevertheless, restrictive anti-alcohol laws were introduced in a number ofcountries. Moreover, the efforts ofAmerican prohibition ists furthered the larger process of American cultural expansion by emphasizing achievements of the U.S. in economic modernization and technical advancement. This episode in American cultural expansion occurred with the support of anti alcohol groups in foreign countries that embraced the message equating American reform with modernity. Prohibitionists abroad colluded in the process, thereby accepting a form ofAmerican cultural hegemony. En 1920, par l'intermédiaire de la World League against Alcoholism, les prohibi tionnistes américains se sont efforcés de pousser leur lutte contre l'alcool au-delà des frontières des États-Unis. Cependant, le sentiment anti-américain, l'opposition complexe des classes et de la culture à l'endroit de la prohibition ainsi que la mauvaise presse dont l'expérience américaine a fait l'objet ont fait échouer leurs efforts. Néanmoins, plusieurs pays ont adopté des lois restrictives contre l'alcool. Qui plus est, les efforts des prohibitionnistes américains ont favorisé l'expansion de la culture américaine en mettant en valeur les réussites des É.-u. au chapitre de la modernisation économique et de l'avancement de la technologie. -

Alcohol Effects on People; 00 Social Responsibility for the Control of the Use of Beverage; and (5) the Social Responsibility for the Treatment of Individuals

DOC- NT RESUME ED 140 180 CG 011 461 TITLE Alcohol Education: Curriculum Guide for Grades 7-12. INSTITUTION New York State Education Dept., Albany. Bureau of Drug Education. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 144p.; For relat d document, see CG 011 462 EERS PRICE MF-$0.83 BC-$7.35 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alcohol Education; *Alcoholic Beverages; Class Activities; Curriculum Guides; *Drinking; Drug Education; Health Education; *Learning Activities; Recreational Activities; *Secondary Education; Socially Deviant Behavior; Teaching Guides AB TRACT This curriculum guide is designed as an interdisciplinary resource on alcohol education for teachers of Grades 7-12. tevelopmental traits are discussed, and objectives and learning experiences are presented. The following topics are covered: ro the nature of alcohci;(2) factors influencing the use of alcoholic beverages; (3) alcohol effects on people; 00 social responsibility for the control of the use of beverage; and (5) the social responsibility for the treatment of individuals. A division is made between Grades 7-9 and 10-12, with each set of three grades considered separately. (Author/OLL)' Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for -

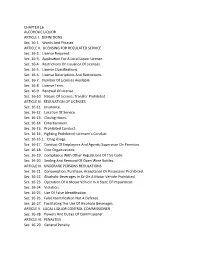

CHAPTER 16 ALCOHOLIC LIQUOR ARTICLE I. DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1

CHAPTER 16 ALCOHOLIC LIQUOR ARTICLE I. DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1. Words And Phrases. ARTICLE II. LICENSING FOR REGULATED SERVICE Sec. 16-2. License Required. Sec. 16-3. Application For A Local Liquor License. Sec. 16-4. Restrictions On Issuance Of Licenses. Sec. 16-5. License Classifications. Sec. 16-6. License Descriptions And Restrictions. Sec. 16-7. Number Of Licenses Available. Sec. 16-8. License Term. Sec. 16-9. Renewal Of License. Sec. 16-10. Nature Of License; Transfer Prohibited. ARTICLE III. REGULATION OF LICENSES Sec. 16-11. Insurance. Sec. 16-12. Location Of Service. Sec. 16-13. Closing Hours. Sec. 16-14. Entertainment. Sec. 16-15. Prohibited Conduct. Sec. 16-16. Fighting Prohibited; Licensee's Conduct. Sec. 16-16.1. Drug Usage. Sec. 16-17. Conduct Of Employees And Agents; Supervisor On Premises. Sec. 16-18. Civic Organizations. Sec. 16-19. Compliance With Other Regulations Of This Code. Sec. 16-20. Sealing And Removal Of Open Wine Bottles. ARTICLE IV. UNDERAGE PERSONS REGULATIONS Sec. 16-21. Consumption, Purchase, Acceptance Or Possession Prohibited. Sec. 16-22. Alcoholic Beverages In Or On A Motor Vehicle Prohibited. Sec. 16-23. Operation Of A Motor Vehicle In A State Of Impairment. Sec. 16-24. Violation. Sec. 16-25. Use Of False Identification. Sec. 16-26. False Identification Not A Defense. Sec. 16-27. Facilitating The Use Of Alcoholic Beverages. ARTICLE V. LOCAL LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSIONER Sec. 16-28. Powers And Duties Of Commissioner. ARTICLE VI. PENALTIES Sec. 16-29. General Penalty. ARTICLE I DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1. WORDS AND PHRASES. Unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall be construed according to the definitions set forth below: ACTING IN THE COURSE OF BUSINESS. -

David Lloyd George and Temperance Reform Philip A

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1980 The ac use of sobriety : David Lloyd George and temperance reform Philip A. Krinsky Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Krinsky, Philip A., "The cause of sobriety : David Lloyd George and temperance reform" (1980). Honors Theses. Paper 594. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll/11111 3 3082 01 028 9899 - The Cause of Sobriety: David Lloyd George and Temperance Reform Philip A. Krinsky Contents I. Introduction: 1890 l II. Attack on Misery: 1890-1905 6 III. Effective Legislation: 1906-1918 16 IV. The Aftermath: 1918 to Present 34 Notes 40 Bibliographical Essay 47 Temperance was a major British issue until after World War I. Excessive drunkenness, not alcoholism per se, was the primary concern of the two parliamentary parties. When Lloyd George entered Parliament the two major parties were the Liberals and the Conservatives. Temperance was neither a problem that Parliament sought to~;;lv~~ nor the single issue of Lloyd George's public career. Rather, temperance remained within a flux of political squabbling between the two parties and even among the respective blocs within each Party. Inevitably, compromises had to be made between the dissenting factions. The major temperance controversy in Parliament was the issue of compensation. Both Parties agreed that the problem of excessive drunkenness was rooted in the excessive number of public houses throughout Britain. -

July 29, 2013 Alcohol Policy in Wisconsin History

July 29, 2013 Alcohol Policy in Wisconsin History No single aspect of Wisconsin’s history, regulatory system or ethnic composition is responsible for our alcohol environment. Many statements about Wisconsin carry the implicit assumption that our destructive alcohol environment (sometimes called the alcohol culture) has always been present and like Wisconsin’s geographic features it is unchanging and unchangeable. This timeline offers an alternative picture of Wisconsin’s past. Today’s alcohol environment is very different from early Wisconsin where an active temperance movement existed before commercial brewing. Few people realize that many Wisconsin communities voted themselves “dry” before Prohibition. While some of those early policies are impractical and even quaint by modern standards, they suggest our current alcohol environment evolved over time. The policies and practices that unintentionally result in alcohol misuse are not historical treasures but simply ideas that may have outlived their usefulness. This timeline includes some historical events unrelated to Wisconsin to place state history within the larger context of American history. This document does not include significant events relating to alcohol production in Wisconsin. Beer production, as well as malt and yeast making were important aspects of Wisconsin’s, especially Milwaukee’s, history. But Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance, its late President, Edmund Fitzgerald, industrial giant Allis Chalmers, shipbuilding and the timber industry have all contributed to Wisconsin’s history. Adding only the brewing industry to this time-line would distort brewing’s importance to Wisconsin and diminishes the many contributions made by other industries. Alcohol Policy in Wisconsin History 1776: Benjamin Rush, a physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, is considered America’s first temperance leader.