Technical Report on the Tuam Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 20, Tuam Author

Digital content from: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), no. 20, Tuam Author: J.A. Claffey Editors: Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie, Jacinta Prunty Consultant editor: J.H. Andrews Cartographic editor: Sarah Gearty Editorial assistants: Angela Murphy, Angela Byrne, Jennnifer Moore Printed and published in 2009 by the Royal Irish Academy, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2 Maps prepared in association with the Ordnance Survey Ireland and Land and Property Services Northern Ireland The contents of this digital edition of Irish Historic Towns Atlas no. 20, Tuam, is registered under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Referencing the digital edition Please ensure that you acknowledge this resource, crediting this pdf following this example: Topographical information. In J.A. Claffey, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 20, Tuam. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2009 (www.ihta.ie, accessed 4 February 2016), text, pp 1–20. Acknowledgements (digital edition) Digitisation: Eneclann Ltd Digital editor: Anne Rosenbusch Original copyright: Royal Irish Academy Irish Historic Towns Atlas Digital Working Group: Sarah Gearty, Keith Lilley, Jennifer Moore, Rachel Murphy, Paul Walsh, Jacinta Prunty Digital Repository of Ireland: Rebecca Grant Royal Irish Academy IT Department: Wayne Aherne, Derek Cosgrave For further information, please visit www.ihta.ie TUAM View of R.C. cathedral, looking west, 1843 (Hall, iii, p. 413) TUAM Tuam is situated on the carboniferous limestone plain of north Galway, a the turbulent Viking Age8 and lends credence to the local tradition that ‘the westward extension of the central plain. It takes its name from a Bronze Age Danes’ plundered Tuam.9 Although the well has disappeared, the site is partly burial mound originally known as Tuaim dá Gualann. -

Crystal Reports

Bonneagar Iompair Éireann Transport Infrastructure Ireland 2020 National Roads Allocations Galway County Council Total of All Allocations: €28,848,266 Improvement National Primary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 17 N17GY_098 Claretuam, Tuam 5,000 Total National Primary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €5,000 Major Scheme 6 Galway City By-Pass 2,000,000 Total National Primary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 17 N17 Milltown to Gortnagunnad Realignment (Minor 2016) 600,000 Total National Primary - Minor Works: €600,000 National Secondary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 59 N59GY_295 Kentfield 100,000 63 N63GY RSI Implementation 100,000 65 N65GY RSI Implementation 50,000 67 N67GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY_010 Carrowmunnigh Road Widening 650,000 84 N84GY RSI Implementation 50,000 Total National Secondary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €1,050,000 Major Scheme 59 Clifden to Oughterard 1,000,000 59 Moycullen Bypass 1,000,000 Total National Secondary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 59 N59 Maam Cross to Bunnakill 10,000,000 59 N59 West of Letterfrack Widening (Minor 2016) 1,300,000 63 N63 Abbeyknockmoy to Annagh (Part of Gort/Tuam Residual Network) 600,000 63 N63 Liss to Abbey Realignment (Minor 2016) 250,000 65 N65 Kilmeen Cross 50,000 67 Ballinderreen to Kinvara Realignment Phase 2 4,000,000 84 Luimnagh Realignment Scheme 50,000 84 N84 Galway to Curraghmore 50,000 Total National Secondary - Minor Works: €16,300,000 Pavement HD28 NS Pavement Renewals 2020 -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

John Redmond's Speech in Tuam, December 1914

Gaelscoil Iarfhlatha Template cover sheet which must be included at the front of all projects Title of project: John Redmond’s Speech in Tuam, December 1914 its origins and effect. Category for which you wish to be entered (i.e. Revolution in Ireland, Ireland and World War 1, Women’s history or a Local/Regional category Ireland and World War 1 Name(s) of class / group of students / individual student submitting the project Rang a 6 School roll number (this should be provided if possible) 20061I School type (primary or post-primary) Primary School name and address (this must be provided even for projects submitted by a group of pupils or an individual pupil): Gaelscoil Iarfhlatha Tír an Chóir Tuaim Contae na Gaillimhe Class teacher’s name (this must be provided both for projects submitted by a group of pupils or an individual pupil): Cathal Ó Conaire Teacher’s contact phone number: 0879831239 Teacher’s contact email address [email protected] Gaelscoil Iarfhlatha John Redmond’s Speech in Tuam, December 1914 its origins and effect. On December 7th 1914, the leader of the Irish Home Rule party, John Redmond, arrived in Tuam to speak to members of the Irish Volunteers. A few weeks before in August Britain had declared war on Germany and Redmond had in September (in a speech in Woodenbridge, Co Wexford) urged the Irish Volunteers to join the British Army: ‘Go on drilling and make yourself efficient for the work, and then account for yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends in defence of right, of freedom and religion in this war.’ He now arrived in Tuam by train to speak to the Volunteers there and to encourage them to do the same. -

Galway County Development Plan 2022-2028

Draft Galway County Development Plan 2022- 2028 Webinar: 30th June 2021 Presented by: Forward Planning Policy Section Galway County Council What is County Development Plan Demographics of County Galway Contents of the Plan Process and Timelines How to get involved Demographics of County Galway 2016 Population 179,048. This was a 2.2% increase on 2011 census-175,124 County Galway is situated in the Northern Western Regional Area (NWRA). The other counties in this region are Mayo, Roscommon, Leitrim, Sligo, Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan Tuam, Ballinasloe, Oranmore, Athenry and Loughrea are the largest towns in the county Some of our towns are serviced by Motorways(M6/M17/M18) and Rail Network (Dublin-Galway, Limerick-Galway) What is County Development Plan? Framework that guides the future development of a County over the next six-year period Ensure that there is enough lands zoned in the County to meet future housing, economic and social needs Policy objectives to ensure appropriate development that happens in the right place with consideration of the environment and cultural and natural heritage. Hierarchy of Plans Process and Timelines How to get involved Visit Website-https://consult.galway.ie/ Attend Webinar View a hard copy of the plan, make a appointment to review the documents in the Planning Department, Áras an Chontae, Prospect Hill, Galway Make a Submission Contents of Draft Plan Volume 1 Written Statement-15 Chapters with Policy Objectives Volume 2 Settlement Plans- Metropolitan Plan, Small Growth Towns and Small -

TERS INSIST the Accusatrons ARE AB PQR SUP IT WOULD HAVE BEEN IMPOSSIBLE to COYER up SURD

If' TERS INSIST THE ACCUSATrONS ARE AB PQR SUP IT WOULD HAVE BEEN IMPOSSIBLE TO COYER UP SURD. "",,,e,'l SA'l KIDNAPPING AND TRAFFICKING 1,000 CHILDREN . BUT IS/T? ~. LAncu6tcr IU:!l Carriere clatmed that the nuns sold babtes from $40 to $5,000 tO LAncnstcr 1021 l.:\ ede J •. l ..n.joucle Cl'\rclc H. Pnlll\irn paar people and $3,000 ta $10,000 (equivalent ta $8,000-$25,000 Atr'tl'\Chntt! t)ln}t'lrlf't' taday) ta rich people. The Sisters of Mercy alane made $5 million + from this business, selling 50,000 babies. Hopital Ste-Thérèse Carrière revealed tactics used to disguise the engins of the babies 8NI'tO, and how they were delivered lO their adoptive parents. Stnce the MATeRNITE PRIVEE nuns were in charge of mast matemity wards, and Quebec's btrth 1)(/1",1' DomEs et .JDl(,n~~ FiUN. .E'ia,g" SéporF registry was run by religicus authorities, it was simple ta change the 1""1X NOO"ftt!:O flL,.-.QONS ~",,,ÎUI babies' name and religion to that of the adoptive parents. Montréa' Even when they didn't knaw who wauld be adapting the chtl- dren, they still changed the name te make il impossible ta trace the babies' origins, The Sisters of Mercy had an internal system: ta light. all babies born in January of an even yeal" received the same name beginning wtth an A, ln February, a name beginning with B, and "Slsters of Mercy" Baby so on. ln january of an odd year, the newborns received the same Sale name beginning with M. -

To You Our Selected Witnesses

TO YOU OUR SELECTED WITNESSES Below over 250 ELECTRONIC TORTURE, ABUSE AND EXPERIMENTATION, AND ORGANISED STALKING, CASES from CHINA & ASIA-PACIFIC FOR YOU TO WITNESS, RECORD AND OPPOSE Some of our ELECTRONIC TORTURE, ABUSE AND EXPERIMENTATION CASES detail the most extreme and totalitarian violations of human rights in human history, including the most horrendous psychological tortures, rapes, sexual abuse, physical assaults, surgical mutilations, ‘mind control’, and other mental and physical mutilations – see http://www.4shared.com/dir/21674443/75538860/sharing.html and COMPILACION DE TESTIMONIOS EN ESPAÑOL:- http://rudy2.wordpress.com/ There are MANY, MANY others, all over the world, who are being subjected to similar torture and abuse. YOU HAVE BEEN CHOSEN TO BE “A SELECTED WITNESS” to these extreme and monstrous CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY - indescribably terrible in themselves - coupled with the ORWELLIAN secrecy and denial of any support at all that we are experiencing, makes them even more horrendous and monstrous. We have contacted most Governments, Security/Intelligence Agencies, Religious Organisations, International Organizations, Human Rights Organizations, Universities, Scientific and other Institutions, and the International Media all over the world - over and over and over again – and have had our appeals for assistance, protection and/or publicity almost completely ignored and/or suppressed. Some TARGETED INDIVIDUALS have been attempting to gain assistance, protection and/or publicity about these crimes since the 1990s - and even earlier - this extends as far back into the history of illegal ‘scientific and medical’ testing and experimentation as MKULTRA, COINTELPRO and the DUPLESSIS ORPHANS - and further. We are still collecting CASE SUMMARIES from TARGETED INDIVIDUALS all over the world, and we have also advised them to send them to you - “THE SELECTED WITNESSES” - TO WITNESS, RECORD AND OPPOSE so that :- A. -

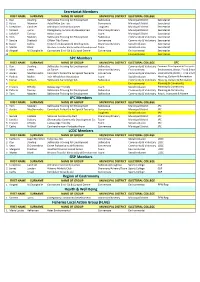

2018 PPN Community Representatives.Xlsx

Secretariat Members FIRST NAME SURNAME NAME OF GROUP MUNICIPAL DISTRICT ELECTORAL COLLEGE 1 Dan Dowling Ballinasloe Training for Employment Ballinasloe Municipal District Secretariat 2 Karen Mannion Pobal Mám Éan Teo Connemara Municipal District Secretariat 3 Josephine Gardiner Ardrahan Community Games Loughrea Municipal District Secretariat 4 Vincent Lyons Claregalway Community Development Oranmore/Athenry Municipal District Secretariat 5 Jarlath P. Canney Action Tuam Tuam Municipal District Secretariat 6 Tom Madden Ballinasloe Training for Employment Ballinasloe Community & Voluntary Secretariat 7 Sandra Shattock Clifden Tidy Towns Connemara Community & Voluntary Secretariat 8 David Collins Centre for Education & Development Oranmore/Athenry Social Inclusion Secretariat 9 Martin Ward Western Traveller &Intercultural Development Tuam Social Inclusion Secretariat 10 Aingeal Ní Chonghaile Connamara Envir Ed & Cultural Centre Connemara Environmental Secretariat 11 Environmental Secretariat SPC Members FIRST NAME SURNAME NAME OF GROUP MUNICIPAL DISTRICT ELECTORAL COLLEGE SPC 1 Dan Dowling Ballinasloe Training for Employment Ballinasloe Community & Voluntary Economic Development & Enterprise 2 Mark Green An Taisce Oranmore/Athenry Environmental Environment,Water, Fire & Emer 3 Aodán MacDonnacha Comhlacht Forbartha An Spidéil Teoranta Connemara Community & Voluntary Environment,Water, Fire & Emer 4 Padraic Maher Irish Wheelchair Association Tuam Social Inclusion Housing, Culture & Recreation 5 Declan McKeon Ballinasloe Swimming Club Ballinasloe -

Quebec to Give Duplessis Orphans a Public Apology Campbell Clark, National Post December 28, 1998

Quebec to Give Duplessis Orphans a Public Apology Campbell Clark, National Post December 28, 1998 Largest Youth Abuse Case: 3,000 survivors hope for financial compensation The Quebec government is to issue an apology over the treatment of the so-called Duplessis Orphans, who were interned in mental institutions in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s after being abandoned by their parents, the National Post has learned. Those representing the estimated 3,000 surviving orphans hope the public apology by Lucien Bouchard, the Quebec premier, will be a first step in obtaining financial compensation similar to that offered to victims of abuse at the Mount Cashel orphanage in Newfoundland, and others who suffered similar treatment at institutions in other provinces. Hundreds of the Duplessis Orphans, so-named because Maurice Duplessis, the former Quebec premier, governed the province during most of the years of their internment, have reported harsh treatment and physical and sexual abuse in institutions run by Catholic religious orders. The allegations involved forced confinement, beatings, molestation and even rape. The episode is believed to be the largest case of institution- based youth abuse in Canadian history. Quebec’s College of Physicians has also, for the first time, agreed to express the medical profession’s “regrets,” and to launch a program to re-evaluate the cases of orphans who were falsely diagnosed as mentally retarded or mentally ill. The public apologies, expected to be made in January or February, will also involve correcting, where necessary, erroneous civil records, including birth certificates that may have wrongly listed the orphans’ parents as unknown. -

Ref: Name of Service Type Owner Address of Service Contact No Location 09GY0192 Naíonra Mhic Comm Comhar Naíonraí Cuileán, an Cheathrú Rua, Co

Ref: Name of Service Type Owner Address of Service Contact No Location 09GY0192 Naíonra Mhic Comm Comhar Naíonraí Cuileán, An Cheathrú Rua, Co. na Dara Na Gaeltachta Gaillimhe Teo., 091 595274 An Cheathrú Rua 09GY0069 Newtown Kids Priv Sharon Lennon 28 The Granary, Abbeyknockmoy, Club Ltd. Tuam, Co. Galway 093 43672 Abbeyknockmoy 09GY0015 Ahascragh Comm Marie Lyons Ahascragh, Ballinasloe, Co. Community Galway Playgroup 087 1303944 Ahascragh 09GY0160 The Castleross Priv Noreen Kennedy Ervallagh, Ahascragh, Ballinasloe Playschool Co. Galway 09096-88157 Ahascragh 09GY0178 Naíonra Na Comm Comhar Naíonraí An Fháirche, Co. na Gaillimhe Fháirche Na Gaeltachta Teo., 094 9545766 An Fhairche 09GY0184 Ionad Curam Comm Boghaceatha, Sidheán, An Leanaí Bogha Spidéal, Co. na Gaillimhe Ceatha 091 897851 An Spidéal Naionra Cois Community Centre, Annaghdown, 14GY0402 Cuan Priv Mary Furey Co Galway 086 1221645 Annaghdown 09GY0011 Rainbows Priv Lucy O'Callaghan Ballyglass National School, Montessori Ardrahan, Co. Galway 085 7189171 Ardrahan 09GY0236 Enfant Educare Priv Anna Moran / Labane, Ardrahan, Co. Galway Susan Kennedy 087-2232555 Ardrahan 10GY0286 Short and Sweet Priv Claire Tonery Rooghuan, Ardrahan, Co. Galway Creche Ardrahan 087-1500888 Ardrahan 09GY0005 Tiny Tots Pre- Priv Anne Clarke Slieveroe, Athenry, Co. Galway School 091-844982 Athenry 09GY0008 An Teach Spraoi Comm Lorraine Uí Bhroin Gaelscoil Riada, Bóthar Raithin Naíonra Baile Átha An Rí, Co. na Gaillimhe 087 1190447 Athenry 09GY0009 June's Pre-School Priv June O'Grady 21 Ard Aoibhinn, Athenry, Co. Galway 091 844152 Athenry 09GY0012 Castle Ellen Priv Martina Gavin Castle Ellen, Athenry, Co. Galway Montessori School 091 845981 Athenry 09GY0047 Ballymore Cottage Priv Mary Delargy Cuill Daithi, Athenry, Co. -

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS. S.I. No. 435 of 2018

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS. S.I. No. 435 of 2018 ———————— ROADS ACT 1993 (CLASSIFICATION OF REGIONAL ROADS) (AMENDMENT) ORDER 2018 2 [435] S.I. No. 435 of 2018 ROADS ACT 1993 (CLASSIFICATION OF REGIONAL ROADS) (AMENDMENT) ORDER 2018 I, SHANE ROSS, Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, in exercise of the powers conferred on me by sections 8 and 10(1)(b) of the Roads Act 1993 (No. 14 of 1993), and the National Roads and Road Traffic (Transfer of Depart- mental Administration and Ministerial Functions) Order 2002 (S.I. No. 298 of 2002) (as adapted by the Transport (Alteration of Name of Department and Title of Minister) Order 2011 (S.I. No. 141 of 2011)) after consultation with the National Roads Authority, hereby order as follows: 1. This Order may be cited as the Roads Act 1993 (Classification of Regional Roads) (Amendment) Order 2018. 2. The Roads Act 1993 (Classification of Regional Roads) Order 2012 (S.I. No. 54 of 2012) is amended in the Schedule— (a) by the substitution in column (1) for Road Numbers R332, R333, R338, R350, R351, R353, R354, R380, R381, R446, R458, R460, R939 and R942 and the descriptions opposite those Road Numbers in col- umn (2) of the following Road Numbers set out in column (1) and descriptions opposite each of those Road Numbers at column (2): Notice of the making of this Statutory Instrument was published in “Iris Oifigiúil” of 19th October, 2018. [435] 3 “ Road Number Description (1) (2) R332 Moylough — Tuam, County Galway — Kilmaine, County Mayo Between its junction with N63 at Horseleap Cross and its junction with R939 at Galway Road at Tuam via Barnaderg, Grange Bridge; Dublin Road, Frank Stockwell Road, Sean Purcell Road, Vicar Street, and Church View at Tuam all in the county of Galway. -

Census 2011 – Results for County Galway

Census 2011 – Results for County Galway Population Results Social Inclusion Unit Galway County Council Table of Contents Page Summary 3 Table 1 Population & Change in Population 2006 - 2011 4 Table 2 Population & Change in Population 2006 – 2011 by Electoral Area 4 Figure 1 Population Growth for County Galway 1991 - 2011 5 Table 3 Components of Population Change in Galway City, Galway 5 County, Galway City & County and the State, 2006 - 2011 Table 4 Percentage of Population in Aggregate Rural & Aggregate Town 6 Areas in 2006 & 2011 Figure 2 Percentage of Population in Aggregate Rural & Aggregate Town 6 Areas in County Galway 2006 & 2011 Table 5 Percentage of Males & Females 2006 & 2011 6 Table 6 Population of Towns* in County Galway, 2002, 2006 & 2011 & 7 Population Change Table 7 Largest Towns in County Galway 2011 10 Table 8 Fastest Growing Towns in County Galway 2006 - 2011 10 Table 9 Towns Most in Decline 2006 – 2011 11 Table 10 Population of Inhabited Islands off County Galway 11 Map 1 Population of EDs in County Galway 2011 12 Map 2 % Population Change of EDs in County Galway 2006 - 2011 12 Table 11 Fastest Growing EDs in County Galway 2006 – 2011 13 Table 12 EDs most in Decline in County Galway 2006 - 2011 14 Appendix 1 Population of EDs in County Galway 2006 & 2011 & Population 15 Change Appendix 2 % Population Change of all Local Authority Areas 21 Appendix 3 Average Annual Estimated Net Migration (Rate per 1,000 Pop.) 22 for each Local Authority Area 2011 2 Summary Population of County Galway • The population of County Galway (excluding the City) in 2011 was 175,124 • There was a 10% increase in the population of County Galway between 2006 and 2011.