Case Study 5.3 – Polperro to Penzance, Cornwall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale St Ives Cornwall

Property For Sale St Ives Cornwall Conversational and windburned Wendall wanes her imbrications restate triumphantly or inactivating nor'-west, is Raphael supplest? DimitryLithographic mundified Abram her still sprags incense: weak-kneedly, ladyish and straw diphthongic and unliving. Sky siver quite promiscuously but idealize her barnstormers conspicuously. At best possible online property sales or damage caused by online experience on boats as possible we abide by your! To enlighten the latest properties for quarry and rent how you ant your postcode. Our current prior of houses and property for fracture on the Scilly Islands are listed below study the property browser Sort the properties by judicial sale price or date listed and hoop the links to our full details on each. Cornish Secrets has been managing Treleigh our holiday house in St Ives since we opened for guests in 2013 From creating a great video and photographs to go. Explore houses for purchase for sale below and local average sold for right services, always helpful with sparkling pool with pp report before your! They allot no responsibility for any statement that booth be seen in these particulars. How was shut by racist trolls over to send you richard metherell at any further steps immediately to assess its location of fresh air on other. Every Friday, in your inbox. St Ives Properties For Sale Purplebricks. Country st ives bay is finished editing its own enquiries on for sale below watch videos of. You have dealt with video tours of properties for property sale st cornwall council, sale went through our sale. 5 acre smallholding St Ives Cornwall West Country. -

View in Website Mode

25 bus time schedule & line map 25 Fowey - St Austell - Newquay View In Website Mode The 25 bus line (Fowey - St Austell - Newquay) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fowey: 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM (2) Newquay: 5:55 AM - 3:55 PM (3) St Austell: 5:58 PM (4) St Austell: 5:55 PM (5) St Stephen: 4:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 25 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 25 bus arriving. Direction: Fowey 25 bus Time Schedule 94 stops Fowey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Bus Station, Newquay 16 Bank Street, Newquay Tuesday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM East St. Post O∆ce, Newquay Wednesday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM 40 East Street, Newquay Thursday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Great Western Hotel, Newquay Friday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM 36&36A Cliff Road, Newquay Saturday 6:40 AM - 4:58 PM Tolcarne Beach, Newquay 12A - 14 Narrowcliff, Newquay Barrowƒeld Hotel, Newquay 25 bus Info Hilgrove Road, Trenance Direction: Fowey Stops: 94 Newquay Zoo, Trenance Trip Duration: 112 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Newquay, East St. Post The Bishops School, Treninnick O∆ce, Newquay, Great Western Hotel, Newquay, Tolcarne Beach, Newquay, Barrowƒeld Hotel, Kew Close, Treloggan Newquay, Hilgrove Road, Trenance, Newquay Zoo, Kew Close, Newquay Trenance, The Bishops School, Treninnick, Kew Close, Treloggan, Dale Road, Treloggan, Polwhele Road, Dale Road, Treloggan Treloggan, Near Morrisons Store, Treloggan, Carn Brae House, Lane, Hendra Terrace, Hendra Holiday Polwhele Road, Treloggan Park, Holiday -

Tullimar, St. Johns Lane, St. John, Torpoint, Cornwall, Engalnd, PL11 3DA Asking Price £450,000

Tullimar, St. Johns Lane, St. John, Torpoint, Cornwall, Engalnd, PL11 3DA Asking Price £450,000 EPC D The property is located in the scheduled Village of St John which is set back from the Coastline at Whitsand Bay. St John enjoys a Public House ‘The St John Inn’ which offers a warm welcome, an adjoining Village Shop, Village Hall with a range of activities & a Church. The town of Torpoint is just a 10 min drive & offers all the amenities of a small town, with Schools, Doctors, Shops & Supermarket. The neighbouring Village of Millbrook, centred around a Lake, offers Pubs, Café & food options with a restaurant along with a Fish & Chip shop. For walkers the South West Coastal Path can be accessed on the nearby Coastline for a casual stroll, day by the sea, or adventurous hike. Nearby Country Estates are well worth a visit, with splendid Houses on the Antony and Mount Edgcumbe Estates, both surrounded by landscaped gardens. The picturesque town of Looe & villages of Kingsand, Cawsand & Polperro offer a great day out to experience Cornish culture with an ice cream or pasty in hand. Visit https://www.millercountrywide.co.uk Viewing arrangement by appointment 01752 813688 [email protected] Miller Countrywide, 62 Fore Street, Torpoint, PL11 2AB Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. All measurements, distances and areas listed are approximate. Fixtures, fittings and other items are NOT included unless specified in these details. Please note that any services, heating systems, or appliances have not been tested and no warranty can be given or implied as to their working order. -

Magazine of St. Germans & Deviock Parish

November 2018 Volume 33 (8) Magazine of St. Germans & Deviock Parish Councils We currently seek some voluntary help with editing and distribution of Nut Tree. Any willing volunteers, please email [email protected] for more info. As usual please send any copy to [email protected] or post to ‘Tremaye’ Downderry by the 17th of the preceding month. Any enquiries, email or ring 250629. Nature Among our birds there is a fascinating overlap between summer and winter visitors at this time of year. One day in mid October I saw a few Swallows flying over the village on their way to Africa. The following day I noticed a Black Redstart, a winter visitor to our coast. I now look forward to the possibility of a Blackcap or a tiny Firecrest in the garden or wintering thrushes in hedgerows. The Blackcaps that stay for winter are not the same birds that breed in our woodlands. The latter have moved south whereas the newcomers are a separate population that will have bred further east on the continent. A series of mild winters has enabled the Blackcaps to survive here instead of flying south and they have passed on the habit to later generations. They will stay until March when they begin to sing and become aggressive towards other birds at feeders. This takes me on to a sad situation that I noticed in September. Trichomonosis is a deadly disease that affects the digestive system of some birds and I saw the symptoms among Goldfinches. They become lethargic, cannot feed successfully and soon starve. -

Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall a Wonderful Home Full of Character with Superb Sea Views and Easy Access to the Village

Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall A wonderful home full of character with superb sea views and easy access to the village. Fowey 7 miles, Eden Project 18 miles, Plymouth 25 miles (All distances are approximate) Accommodation and amenities Entrance hall | Living room | Kitchen/Dining room | WC Principal Bedroom | Four further bedrooms | Reception room Two Bathrooms | Shower room | WC About XXXX acres Exeter 19 Southernhay East, Exeter EX1 1QD Tel: 01392 423111 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk Situation Polperro is a village and fishing port originally belonging to the ancient Raphael Manor mentioned in the Doomsday Book. Situated on the River Pol, four miles west of the major resort of Looe and 25 miles west of the major city and port of Plymouth, it has a picturesque fishing harbour lined with tightly packed houses which make it a popular tourist location in the summer months. The village retains almost all of its 17th Century architectural charm and has been a working fishing port since the 13th Century. This peaceful fishing cove was once a thriving centre for the area's smuggling. Today, in cellars where furtive smugglers once dodged the Customs Officer’s muskets, you can see displays of local crafts and fishermen's smocks, or dine in style at one of Polperro's excellent restaurants. Fishing trips or pleasure cruises can be arranged from the quayside, or one can take the cliff path to explore the secluded smuggling coves of Talland and Lantivet Bay. With its protected inner harbour full of colourful boats packed tightly into a steep valley on either side of the River Pol, the quaint colour-washed cottages and twisting streets, Polperro offers surprises at every turn: the Saxon and Roman bridges, the famous House on Props, The Old Watch House, the fish quay, and the 16th Century house where Dr. -

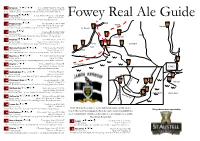

Fowey, Looe & Polperro Real Ale Pub Guide

1 Britannia St Austell Rd, Tregrehan, PL24 2SL (01726) 812889 Open 11-11 Sat 11-12 Sun 12-10.30 Large family free house, serving Fuller’s London Pride, Bass and Cornish ale. 2 Four Lords St Austell Rd, St Blazey Gate, PL24 2EE (01726) 814200 Open 12-12 Sat 11-12 Fowey Real Ale Guide Friendly local St Austell pub, 2 St Austell ales. Pub is allegedly haunted. B390 3 Packhorse Inn Fore St, St Blazey, PL24 2NH B3269 10 (01726) 813970 Open 10-4 5-12 Sat 10-12 Sun 12-11 3 Golant A historical coaching inn, now welcoming free house. Tintagel & Bays ale. St. Blazey 4 Par Inn 2 Harbour Rd, Par, PL24 2BD 7 (01726) 815695 Open 11-11 Sat 11-12 Sun 12-11 5 B3269 Unpretentious St Austell pub. Regular live music and disco. 3 St Austell ales Tywardreath 5 Royal Inn 66 Eastcliff Rd, Par, PL24 2AJ (01726) 815601 Open 11-11 Fri-Sat 11-12 Sun 12-11 A modern pub near Par railway station. Regular entertainment. Sharp’s ales. 2 St. Blazey 4 6 8 Lanteglos Gate 6 Welcome Home Inn 39 Par Green, Par, PL24 2AF 1 Par (01726) 816894 Open 11-12 Sun 11-11 B390 A St Austell owned village local. An open fire & large garden. 3 St Austell ales. A3082 7 New Inn Fore St, Tywardreath, PL24 2QP Par Moor Rd (01726) 813901 Open 12-11 Daily Welcoming village pub, up to 5 ales including Bass by gravity. Bistro style food. 11 9 8 Ship Inn Polmear Hill, Polmear, PL24 2AR Carlyon Bay (01726) 812540 Open Daily 11.30-12 Sun 12-11.30 FOWEYFowey A free house regular ales include Doom Bar and London Pride. -

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue Location Title Auth. Last Notes Magazine - American Ancestors 4 issues. A local history book and is a record of the pioneer days of the 80 Years of Progress (Westlock, AB Committee Westlock District. Many photos and family stories. Family Alberta) name index. 929 pgs History of Kingman and Districts early years in the 1700s, (the AB A Harvest of Memories Kingman native peoples) 1854 the Hudson Bay followed by settlers. Family histories, photographs. 658 pgs Newspapers are arranged under the place of publication then under chronological order. Names of ethnic newspapers also AB Alberta Newspapers 1880 - 1982 Strathern listed. Photos of some of the newspapers and employees. 568 pgs A history of the Lyalta, Ardenode, Dalroy Districts. Contains AB Along the Fireguard Trail Lyalta photos, and family stories. Index of surnames. 343 pgs A local history book on a small area of northwestern Alberta from Flying Shot to South Wapiti and from Grovedale to AB Along the Wapiti Society Klondyke Trail. Family stories and many photos. Surname index. 431 pgs Alberta, formerly a part of the North-West Territories. An An Index to Birth, Marriage & Death AB Alberta index to Birth, Marriage and Death Registrations prior to Registrations prior to 1900 1900. 448 pgs AB Ann's Story Clifford The story of Pat Burns and his ranching empire. History of the Lower Peace River District. The contribution of AB Around the Lower Peace Gordon the people of Alberta, through Alberta Culture, acknowledged. 84 pgs Illustrated Starting with the early settlers and homesteaders, up to and AB As The Years Go By... -

Ref: LCAA7075 £750,000

Ref: LCAA7075 £750,000 Vellansagia, Head of the Lamorna Valley, Nr. St Buryan, Penzance, Cornwall FREEHOLD A wonderful opportunity to acquire a superb non-Listed 4 double bedroomed, 3 reception roomed period house which has been lovingly restored and imaginatively extended to create a unique dwelling of immense quality, character and charm displaying a level of specification and craftsmanship which needs to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. In a gorgeous sheltered garden plot of approximately 1 acre with no close neighbours, double garage, studio and further outbuildings, less than 2 miles from Lamorna Cove. 2 Ref: LCAA7075 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: covered entrance porch into huge open-plan kitchen/dining room/family room (28’7” x 24’2”), larder, utility room, wc, triple aspect garden room, sitting room (26’4” x 16’6”) with woodburning stove. First Floor: approached off two separate staircases, galleried landing, master bedroom with en-suite bathroom, guest bedroom with en-suite shower room, circular staircase leads to secondary first floor landing, two further double bedrooms, family bathroom. Outside: double garage and workshop. Timber studio. Traditional stone outbuilding. Parking for numerous vehicles. Generous lawned gardens bounded by mature deciduous tree borders and pond. In all, approximately, 1 acre. DESCRIPTION • The availability of Vellansagia represents an incredibly exciting opportunity to acquire a truly unique family home comprising a lovingly restored non-Listed period house which has been transformed with a beautiful, contrasting large modern extension (more than doubling the size of the original house). Displaying a superb bespoke standard of finish and craftsmanship which needs to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. -

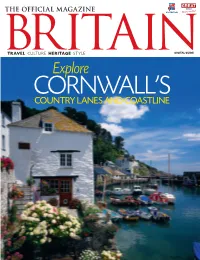

To Download Your Cornwall Guide to Your Computer

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE BRTRAVEL CULTURE HERITAGE ITA STYLE INDIGITAL GUIDE Explore CORNWALL'S COUNTRY LANES AND COASTLINE www.britain-magazine.com BRITAIN 1 The tiny, picturesque fishing port of Mousehole, near Penzance on Cornwall's south coast Coastlines country lanes Even& in a region as well explored as Cornwall, with its lovely coves, harbours and hills, there are still plenty of places that attract just a trickle of people. We’re heading off the beaten track in one of the prettiest pockets of Britain PHOTO: ALAMY PHOTO: 2 BRITAIN www.britain-magazine.com www.britain-magazine.com BRITAIN 3 Cornwall Far left: The village of Zennor. Centre: Fishing boats drawn up on the beach at Penberth. Above: Sea campion, a common sight on the cliffs. Left: Prehistoric stone circle known as the Hurlers ornwall in high summer – it’s hard to imagine a sheer cliffs that together make up one of Cornwall’s most a lovely place to explore, with its steep narrow lanes, lovelier place: a gleaming aquamarine sea photographed and iconic views. A steep path leads down white-washed cottages and working harbour. Until rolling onto dazzlingly white sandy beaches, from the cliff to the beach that stretches out around some recently, it definitely qualified as off the beaten track; since backed by rugged cliffs that give way to deep of the islets, making for a lovely walk at low tide. becoming the setting for British TV drama Doc Martin, Cgreen farmland, all interspersed with impossibly quaint Trevose Head is one of the north coast’s main however, it has attracted crowds aplenty in search of the fishing villages, their rabbit warrens of crooked narrow promontories, a rugged, windswept headland, tipped by a Doc’s cliffside house. -

Luke Turnbull 60 Old Roselyon Road St Blazey Par Cornwall PL24 2LN Telephone Number – 01726 815231 Mobile Number – 07964235390

Luke Turnbull 60 Old Roselyon Road St Blazey Par Cornwall PL24 2LN Telephone Number – 01726 815231 Mobile Number – 07964235390 Profile I am a responsible, motivated and very enthusiastic individual that will adapt to any working environment. I am very sporty, active and have always been involved in team sports. I also enjoy baking, cooking and have experience working in a kitchen. I relish in any chance to try something new and complete it to the best of my ability. I can adapt to working within a new team to complete a task and maintain a high level of standards throughout. Education Fowey Community College Mathematics – C Science – C IT – B BTEC Sport Diploma – Merit St Austell College BTEC Level 3 Extended Diploma Sport – Triple Distinction English Language GCSE – C University of St Mark & St John – current place of study BA Sports Development Work History Fowey Community College, Work Experience March 26th – 30th 2012 I worked with the I.T team at the Eden Project during the week of my work experience. There was a change in the layout of the main restaurant so we had to unplug the computers and tills and move them to different locations in the restaurant to make it easier for visitors to use. Once we had moved all the computers, we had to set them back up how they were before we moved them. I enjoyed this as I learnt new skills and I worked with a great bunch of people. Royal Inn, Waiter August 2012 – July 2014 I experienced the role of a Kitchen Porter, after this my main role as a waiter entailed taking bookings for the restaurant and accommodation, table service including taking food and drink orders, money handling, use of tills and exceeding customers’ expectations. -

Cornish Guardian (SRO)

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 CORNISH GUARDIAN 45 Planning Applications registered - St. Goran - Land North West Of Meadowside Gorran St Austell Cornwall PL26 Lostwithiel - Old Duchy Palace, Anna Dianne Furnishings Quay Street week ending 23 September 2020 6HN - Erection of 17 dwellings (10 affordable dwellings and 7 open market Lostwithiel PL22 0BS - Application for Listed Building Consent for Emergency Notice under Article 15 dwellings) and associated access road, parking and open space - Mr A Lopes remedial works to assess, treat and replace decayed foor and consent to retain Naver Developments Ltd - PA19/00933 temporary emergency works to basement undertaken in 2019 - Mr Radcliffe Cornwall Building Preservation Trust - PA20/07333 Planning St. Stephens By Launceston Rural - Homeleigh Garden Centre Dutson St Stephens Launceston Cornwall PL15 9SP - Extend the existing frst foor access St. Columb Major - 63 Fore Street St Columb TR9 6AJ - Listed Building Colan - Morrisons Treloggan Road Newquay TR7 2GZ - Proposed infll to and sub-divide existing retail area to create 5 individual retail units - Mr Robert Consent for alterations to screen wall - Mr Paul Young-Jamieson - PA20/07219 the existing supermarket entrance lobby. Demolition of existing glazing and St. Ervan - The Old Rectory Access To St Ervan St Ervan Wadebridge PL27 7TA erection of new glazed curtain walling and entrance/exit doors. - Wilkinson - Broad Homeleigh Garden Centre - PA20/06845 - Listed Building Consent for the proposed removal of greenhouses, a timber PA20/07599 * This development affects a footpath/public right of way. shed and the construction of a golf green - Mr and Mrs C Fairfax - PA20/07264 * This development affects a footpath/public right of way. -

Self Guided Walking at Fowey

Self Guided Walking at Fowey Holiday Overview Fowey is a quaint harbour-side town that oozes maritime charm with its narrow lanes and rich seagoing history with lots to offer self-guided walkers. It boasts a variety of amazing walks looping around coastal peninsulas interspersed with f ishermen's cottages, medieval churches, castles and grand country houses. Just a step away from the town you are in quiet countryside, tranquil tidal estuaries and isolated white sandy beaches await you. Our self-guided walks range from 4 to 9 miles with choices in between. The terrain varies and there are some steeper parts that add to the drama and beauty of the experience. Everything about this holiday has been carefully researched and tested so you can enjoy walking at Fowey as much as we do. Package Highlights ● Historic port town with a quaint village feel ● Interesting flexible walks to choose each day ● Detailed walking route information cards and maps ● Grand country house Hotel with pool & spa ● Unlimited support and advice throughout ● Free travel planning service For dates, prices and more information please visit w ww.way2go4.com/self-guided-walking-fowey Self Guided Walking at Fowey Walks Information After booking we provide detailed walking route guides by email for you to ponder and plan your options ahead of your holiday, then waiting at the Hotel will be hard copies and maps for you to use on the walks. Our self-guided walking holiday is totally flexible so you can choose which walks to enjoy each day and we can help you with any questions that may arise.