Mount Colden's Trap Dike-Great Slide- S.E. 90'S Slide Traverse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYSDEC & AMR Pilot Reservation System

Updated 04/15/21 NYSDEC & AMR Pilot Reservation System DEC and the Adirondack Mountain Reserve (AMR) launched a no-cost pilot reservation system to address public safety at a heavily traveled stretch on Route 73 in the town of Keene in the Adirondack High Peaks. The Adirondack Mountain Reserve is a privately owned 7,000-acre land parcel located in the town of Keene Valley that allows for limited public access through a conservation easement agreement with DEC. The pilot reservation system does not apply to other areas in the Adirondack Park. The reservation system, operated by AMR, will facilitate safer public access to trailheads through the AMR gate and for Noonmark and Round mountains and improve visitors' trip planning and preparation by ensuring they have guaranteed parking upon arrival. In recent years, pedestrian traffic, illegal parking, and roadside stopping along Route 73 have created a dangerous environment for hikers and motorists alike. These no-cost reservations will be required May 1 through Oct. 31, 2021. Reservations will be required for parking, daily access, and overnight access to these specific trails. Visitors can make reservations beginning April 15 at hikeamr.org. Walk-in users without a reservation will not be permitted. o There is no cost associated with making a reservation. o Those arriving to Keene Valley via Greyhound or Trailways bus lines may present a valid bus ticket from within 24 hours of arrival to the AMR parking lot attendant in lieu of a reservation. o Those being dropped off or arriving by bicycle must check in at the AMR Hiker Parking Lot and produce a valid reservation. -

Page 1 L O N G I S L a N D M O U N T a I N E E R Newsletter of The

LONG ISLAND MOUNTAINEER Newsletter Of The Adirondack Mountain Club,Long Island Chapter SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER i9ss Linda Edwards Editor's Desk THE NOMINATIONS ARE IN The next two months provide the best outing conditions of the year! The Nominating Committee is pre There are no bugs, the weather is senting the following slate of can mild and nature dons its fall didates for the upcoming year. The colors. names will be placed in nomination The Outings Committee has made during the September meeting and an extra special effort to present voted on during the November meet a great array of offerings ( see ing. The Paul Eanzillotta, Ray •• pages 6 and 7). Get out as often as .(eardon and Al Scholl served on the you can. It's the years best season: Nominating Committee. As you are reading this, I'm probably just getting back from my President-— Allen Scholl trip to Colorado and Arizona. I Vice-President - Jim Pelzer thought it was well deserved as I Treasurer - Tom V/all finished the ADK 46ers on July 16 Governor - Herb Coles. on Panther Mt. in the Santanonis. Board of Directors - Larry Braun I'd like to thank my enthusiastic - Bob Young sherpa, Dave, for helping me cele - Stan Weiss brate. I'd also like to thank every one who hiked all those peaks with As of this writing, the Secre me, as I couldn't have done it with tary position has not been filled. out you. The Nominating Committee is still I'd like to encourage those who searching for one. -

2Q Outings List Copy

North Woods Chapter 2nd Quarter Outings April 6, Thursday Hike - Cobble Hill Leaders: email your name and telephone number to [email protected] and the leader will contact you We will hike up Cobble Hill overlooking Mirror Lake and the village of Lake Placid. This trail starts from the driveway to Northwoods School off Mirror Lake Drive. We start through the woods and then scramble up an open rock face with views of Mirror Lake, and then back through the woods to the summit. There are good views of the High Peaks and the Lake Placid Horse Show Grounds from the summit. We will descend via an old ski trail. 3 mi. RT Ascent: 450 ft. Class C Limit 12 April 9, Sunday, at 5:00 pm Chapter Meeting and Potluck Supper Presbyterian Church, Church Street, Saranac Lake Program: Frank and Lethe Lescinsky celebrated their 80th birthdays with a 3-generation family gathering in French Polynesia (Tahiti) where they enjoyed partying, hiking, mountain climbing, snorkeling, scuba diving, shopping, and touring; and will illustrate the culture and beauty with pictures distilled from 12 different cameras. Potluck: Hb - M for main dishes, N - Z for salads and A - Ha for desserts, to share with 10 to 12 people. Please remember to bring table service for yourself and for your guests. April 11, Tuesday Hike - Owl’s Head (Long Lake) Leader: email your name and telephone number to [email protected] and the leader will contact you This Owls Head lies west and southwest of Long Lake and Lake Eaton and has a restored fire observation tower. -

Dix Mountain Wilderness Area Unit Management Plan Amendment

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Lands & Forests Region 5 Dix Mountain Wilderness Area Unit Management Plan Amendment Towns of Elizabethtown, Keene and North Hudson Essex County, New York January 2004 George E. Pataki Erin M. Crotty Governor Commissioner Lead Agency: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation 625 Broadway Albany, NY 12233-4254 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Office of the Commissioner, 14th Floor 625 Broadway, Albany, New York 12233-1010 Phone: (518) 402-8540 • FAX: (518) 402-8541 Website: www.dec.state.ny.us Erin M. Crotty Commissioner MEMORANDUM To: The Record From: Erin M. Crotty Re: Unit Management Plan Dix Mountain Wilderness Area The Unit Management Plan for the Dix Mountain Wilderness Area has been completed. The Plan is consistent with the guidelines and criteria of the Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan, the State Constitution, Environmental Conservation Law, and Department rules, regulations and policies. The Plan includes management objectives and a five year budget and is hereby approved and adopted ___________________________________ Erin M. Crotty, Commissioner PREFACE The Dix Mountain Wilderness Area Unit Management Plan has been developed pursuant to, and is consistent with, relevant provisions of the New York State Constitution, the Environmental Conservation Law (ECL), the Executive Law, the Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan, Department of Environmental Conservation (“Department”) rules and regulations, Department policies and procedures and the State Environmental Quality and Review Act. Most of the State land which is the subject of this Unit Management Plan (UMP) is Forest Preserve lands protected by Article XIV, Section 1 of the New York State Constitution. -

The Cloudsplitter Is Published Quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and Is Distributed to the Membership

The Cloudsplitter Vol. 74 No. 3 July-September 2011 published by the ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB The Cloudsplitter is published quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and is distributed to the membership. All issues (January, April, July, and October) feature activities schedules, trip reports, and other articles of interest to the outdoor enthusiast. All outings should now be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org . If this is not possible, send them to Virginia Traver at [email protected] Echoes should be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org with your login information. The Albany Chapter may be Please send your address and For Club orders & membership For Cloudsplitter related issues, reached at: phone number changes to: call (800) 395-8080 or contact the Editor at: Albany Chapter ADK Adirondack Mountain Club e-mail: [email protected] The Cloudsplitter Empire State Plaza 814 Goggins Road home page: www.adk.org c/o Karen Ross P.O. Box 2116 Lake George, NY 12845-4117 7 Bird Road Albany, NY 12220 phone: (518) 668-4447 Lebanon Spgs., NY 12125 home page: fax: (518) 668-3746 e-mail: [email protected] www.adk-albany.org Submission deadline for the next issue of The Cloudsplitter is August 15, 2011 and will be for the months of October, November, and December. Many thanks to Gail Carr for her sketch of a summer pond scene. September 7 (1st Wednesdays) Business Meeting of Chapter Officers and Committees 6:00 p.m. at Little‘s Lake in Menands Chapter members are encouraged to attend - -

Pages R-39 Through R-43 (PDF)

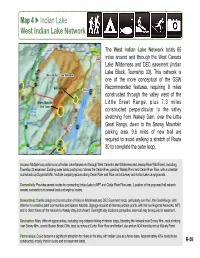

Map 4 ▶ Indian Lake West Indian Lake Network il ra T The West Indian Lake Network totals 65 id c Indian la r P ve - Ri Lake miles around and through the West Canada le r il a v d e th y r C Lake Wilderness and DEC easement (Indian o N Lake Block, Township 33). This network is West Indian Lake Network one of the more conceptual of the GSW JESSU Beaver Brook Sabael RIVER W Recommended features, requiring 9 miles Cliffs FORES constructed through the valley west of the N A Snowy Mountain I E Little Great Range, plus 7.3 miles D K N A Fire Tower I L CEDAR RIVER constructed perpendicular to the valley FLOW stretching from Wakely Dam, over the Little «¬30 Great Range, down to the Snowy Mountain parking area. 9.6 miles of new trail are ni l Sc e tiona required to avoid walking a stretch of Route Na y tr n 30 to complete the outer loop. u o LEWEY C Lewey Lake/Indian Lake h Access: Multiple loop options out of Indian Lake/Sabael and through West Canada Lake Wilderness and Jessup River Wild Forest, including Township 33 easement. Existing outer backcountry loop follows the Cedar Ri ver, passing Wakel oPy nd and Cedar River Flow, with a potential bushwhack up Sugarloaf Mtn. Multiple camping options along Cedar River and Flow, and at Lewey and Indian Lake campgrounds. Connectivity: Provides several routes for connecting Indian Lake to NPT and Cedar River Flow area. Location of the proposed trail network creates connections to several local and regional routes. -

May-July 2008 No

MAY-JULY 2008 No. 0803 chepontuc — “Hard place to cross”, Iroquois reference to Glens Falls hepontuc ootnotes C T H E N E W S L E tt E R O F T H E G L E N S F ALLS- S ARAFT O G A C H A P T E R O F T H E A DIRO N DA C K M O U nt AI N C L U B Hikers alerted to muddy trails By Jim Schneider promote safety, hikers are advised to use Debar Mountain Wild Forest — trails only at lower elevations during the Azure Mountain New York State Department of spring mud season. Lower trails usually Giant Mountain Wilderness — Giant’s Environmental Conservation (DEC) urges are dry soon after snowmelt and are on less Washbowl and Roaring Brook Falls hikers of the Adirondack High Peaks to be erosive soils than the higher peaks. DEC is High Peaks Wilderness — Ampersand cautious during trips into the area and to asking hikers to avoid the following trails Mountain; Cascade; Big Slide; Brothers, postpone hiking on trails above 3,000 feet until muddy conditions have subsided: and Porter from Cascade; avoid all other until otherwise advised. High Peaks Wilderness Area — all trails approaches During warm and wet spring weather, above 3,000 feet—wet, muddy snow con- Hurricane Primitive Area — The many trails in higher and steeper por- ditions prevail, specifically at: Algonquin; Crows and Hurricane Mountain from tions of the Adirondacks can be become Colden; Feldspar; Gothics; Indian Pass; Route 9N hazardous to hikers. In the current muddy Lake Arnold Cross-Over; Marcy; Marcy McKenzie Mt. -

Microsoft Word Good Tidings July October 2018 Website

The Newsletter of the Hurricane Mountain Chapter of ADK Good Tidings July – October 2018 "Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature's peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves." John Muir (1838-1914) Good Tidings July – October 2018 hair Words CA message from Chapter Chair, Christine Barnes COMMUNICATIONS! I would like to clarify how ADK communicates with you. First: The ADK Headquarters in Lake George has your snail mail address and the phone number (that you gave them when you joined) and if you chose to register your e-mail address with them, they have that too. You would then get periodic emails from them about activities, appeals or issues. This is only updated when you tell them to do so. Hurricane cannot change your information for you. Second: Hurricane Chapter gets our ‘snail mail’ mailing labels from ADK. So if your membership lapses, don’t expect to get anything in your snail mail from Hurricane or ADK – except maybe an appeal to re-join. (Please avoid this situation) Third: Hurricane has a ‘newsletter e-mail’ list which Leslie Shipps (our hero!) maintains. This is to get your newsletter electronically – and print it yourself. She adds your name to the list if you send her an e-mail at . [email protected] If you haven’t already done this – please do so unless you really cannot get email. Eventually, we will only send out electronic copies, unless there are special circumstances. -

Gothics Arm Wolfjaws.Pmd

Gothics, Armstrong Mountain, Upper Wolf Jaw Mountain & Lower Wolf Jaw Mountain (The Debbie Hike) Gothics: 8th Peak Hiked, Order #10, Elevation 4736’ Armstrong: 9th Peak Hiked, Order #22, Elevation 4400’ Upper Wolf Jaw: 10th Peak Hiked, Order #29, Elevation 4185’ Lower Wolf Jaw: 11th Peak Hiked, Order #30, Elevation 4175’ Duration: 14.5 Hours Distance: 19+ Miles July 26, 2003 I originally wanted to start with a relatively short hike on a different range, but decided to take advantage of the weather and here’s how the story goes! 7:45 I met my hiking partner, Deb Taylor-James, in Keene at the Elm Tree Inn and we parked her car near Rooster Comb to save space if the smaller lots near the Ausable Club were filled. They were not and I decided to park halfway up the dirt road leading in a loop through the golf course. I even enjoyed this part of the walk since I’d never visited the area before outside of a car. Upon reaching the top of the hill, I noticed the serene setting, elegance of the main building and the beautiful view of Giant Mountain from the golf course. Sawteeth loomed opposite of Giant, behind us. We walked down the Lake Road to the trailhead sign-in book and began the three-mile journey leading to the trails. On this day, a sign saying that the trail was slightly rerouted greeted us. I wondered what this meant during the ensuing hour. My original intent was to hike Gothics, Armstrong and Upper Wolf Jaw. -

Footprints 2018-8-9

Aug. - Sept. 2018 Newsletter Footprints Newsletter of the Adirondack Mountain Club Foothills Chapter Notes from the Foothills Chapter Vice-Chair Upcoming Events "Mature Age" Motto: Don't Be Afraid to Try Something New Wednesday Aug 8, 2018 5pm Foothillers Family Picnic Hope you've been enjoying this wonderful summer as much as I have. I recently celebrated a birthday and a friend asked me what words of wisdom I had to offer. My first thought: Do it Tuesday September 11 while you can! It was rather fitting that this discussion took Hurricane Mt North Trail place on top of a mountain. And from that, my second thought was: Don't be afraid to try something new. This past Tuesday, Sept. 18, (rain date Sat. winter I tried my first cross country ski trip into Camp Santanoni, Oct. 6) and recently, after the purchase of a "lightly" used bike, did my Twin Mountain first bike trip on the Lake George Bike Trail. And the reason I was able to successfully complete and enjoy them both is because Monday, September 24 (rain my Foothills leaders helped and encouraged me all the way. (I date- Tues, September 25) do have to admit my calves were barking at me for 2-3 days Ticeteneyck Mountain after!) So, if you've been reading the trip reports and wishing you could do one but don't have the experience, try it! Just Wednesday, Oct 17, 2018 remember everyone, no matter how experienced, had to NPT cleanup have a "first" time. Any of our outings leaders will be glad to help you. -

Route Hopping on Route 73

PHOTOS BY TK CLIFF NOTES BY RYAN WICHELNS CLIFF NOTES LOGISTICS Guidebook: Blue Lines by Don Mellor is the de facto ice-route reference for the entire Adirondack Park. Seasons: Ice can form in the Adirondack High Peaks as early as October, but often takes until December in lower roadside elevations. By April you’ll be switching to rock shoes. Other crags: It may be the local epicenter, but Keene Valley is only scratching the surface of Adirondack ice. If spending half the day on an approach is fine by you, start hiking from any number of the valley’s trailheads to the big slides and passes of the High Peaks’ interior. The North Face of Gothics (NEI 2, 1,100 feet) and Colden’s Trap Dike (NEI 2, 2,000 feet) are “easy” but exciting and unnervingly exposed climbs, and Avalanche Pass is packed with difficult shorter lines. Route 73 also accesses the North Face of Pitchoff Mountain, ripe with thick ice that tends to come in earlier than some of that around Nick Bullock (U.K) on Ice Storm (NEI 5+ M6), put up by Alex Lowe in Chapel Pond Canyon. Chapel Pond. Accommodation: The I looked back toward the road to see a school bus pass beginning stretch of Route ROUTE along the serpentine mountain highway. I wondered 73 is bordered by designated what the kids in that bus must think to see the wilderness, which means HOPPING mountainsides around them, covered in glassy smears the truly hardy have the and decorated with people hanging like Christmas option to winter-camp almost anywhere, following ON ROUTE 73 ornaments from their faces. -

The Cloudsplitter Is Published Quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and Is Distributed to the Membership

The Cloudsplitter Vol. 79 No. 1 January-March 2016 published by the ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB The Cloudsplitter is published quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and is distributed to the membership. All issues (January, April, July, and October) feature activities schedules, trip reports, and other articles of interest to the outdoor enthusiast. All outings should now be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org . Echoes should be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org with your login information. The Albany Chapter may be Please send your address and For Club orders & membership For Cloudsplitter related issues, reached at: phone number changes to: call (800) 395-8080 or contact the Editor at: Albany Chapter ADK Adirondack Mountain Club e-mail: [email protected] The Cloudsplitter Empire State Plaza 814 Goggins Road home page: www.adk.org c/o Karen Ross P.O. Box 2116 Lake George, NY 12845-4117 7 Bird Road Albany, NY 12220 phone: (518) 668-4447 Lebanon Spgs., NY 12125 home page: fax: (518) 668-3746 e-mail: [email protected] www.adk-albany.org Submission deadline for the next issue of The Cloudsplitter is February 15, 2016 and will be for the months of April, May, and June, 2016. Many thanks to Gail Carr for her cover sketch of winter snows on the Mohawk River. January 6, February 3, March 2 (1st Wednesdays) Business Meeting of Chapter Officers and Committees 6:00 p.m. at Little’s Lake in Menands Chapter members are encouraged to attend - please call Tom Hart at 229-5627 Chapter Meetings are held at the West Albany Fire House (Station #1), 113 Sand Creek Road, Albany.