Ickworth and the Great War (1914-1919)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

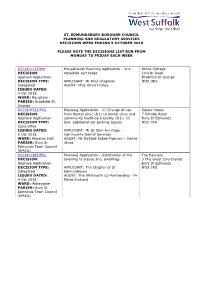

ST. EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 5 OCTOBER 2018 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/18/1133/HH Householder Planning Application - 1no. White Cottage DECISION: detached cart lodge Church Road Approve Application Bradfield St George DECISION TYPE: APPLICANT: Mr Paul Chapman IP30 0BG Delegated AGENT: Miss Olivia Hurley ISSUED DATED: 4 Oct 2018 WARD: Rougham PARISH: Bradfield St. George DC/18/0721/FUL Planning Application - (i) Change of use Saxon House DECISION: from dental clinic (D1) to dental clinic and 7 Hillside Road Approve Application community healthcare facility (D1); (ii) Bury St Edmunds DECISION TYPE: 5no. additional car parking spaces IP32 7EA Committee ISSUED DATED: APPLICANT: Mr St Clair Armitage - 5 Oct 2018 Community Dental Services WARD: Moreton Hall AGENT: Mr Richard Sykes-Popham - Carter PARISH: Bury St Jonas Edmunds Town Council (EMAIL) DC/18/1387/FUL Planning Application - Subdivision of the The Deanery DECISION: dwelling to create 2no. dwellings 3 The Great Churchyard Approve Application Bury St Edmunds DECISION TYPE: APPLICANT: The Chapter of St IP33 1RS Delegated Edmundsbury ISSUED DATED: AGENT: The Whitworth Co-Partnership - Mr 4 Oct 2018 Philip Orchard WARD: Abbeygate PARISH: Bury St Edmunds Town Council (EMAIL) DC/18/1388/LB Application for Listed Building Consent - (i) The Deanery DECISION: subdivision of dwelling to create 2no. 3 The Great Churchyard Approve Application dwellings; (ii) internal alterations to create Bury St Edmunds DECISION TYPE: the division at ground, first and attic floor IP33 1RS Delegated levels; (iii) removal of an existing ISSUED DATED: cloakroom and provision of a new 4 Oct 2018 cloakroom for the new west wing; (iv) WARD: Abbeygate installation of shower room for the PARISH: Bury St Deanery; (v) extension and alteration of Edmunds Town Council gas, electricity, water and waste drainage (EMAIL) systems within the building; (vi) new gas balanced flue on the north wall; (vii) 2no. -

(3 = Easiest to Deliver to 1 = Most Challenging) Estimated Cost

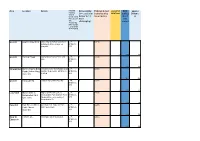

Area Location Details Potential Deliverability Estimated Cost unweighted BCR approx Funding (3 = easiest to (calculated by MCAF total (ebike) Distance Source (Local Travel deliver to 1 = linear metre) nb 0 = m Plan, Section most not 106, challenging) scored Community Infrastructur e Levy, Dept. of Transport) Ipswich Ipswich Waterfront University of Suffolk waterfont LTP, 3 £473k building to Stoke bridge on S106/CIL, quayside DfT 5 44.1 789 Ipswich Portman Road Barrack Corner to Princes St LTP, 3 £214k junc S106/CIL, DfT 3 32.6 360 Stowmarket Chilton Way to Bury This link Lowry Way/Rugby Club LTP, 2 £495k Road (Chilton Way) junction to Bury Rd - BCR to be S106/CIL, Cycle link verified DfT 3 27.4 825 Ipswich Yarmouth Rd London Rd to Bramford Rd - LTP, 3 £327k S106/CIL, DfT 2 22.9 545 Lowestoft Higher Drive to Higher Dr/Woods Loke to LTP, 3 £432k Normanston Park Normanston Park (not incl Park S106/CIL, cycle route tracks) will need crossing of DfT Normanston Dr. 2 22.5 720 Haverhill Park Rd - A1307 to potential new route (or Park LTP, 3 £420k Castle Manor Rd?) spine route S106/CIL, Academy DfT 6 21.8 750 Bury St Cotton Lane Northgate St to Mustow St LTP, 1 £205k Edmunds S106/CIL, DfT 4 15.2 685 Ipswich Princes St link to rail station LTP, 2 £461k S106/CIL, DfT 3 14.9 770 Ipswich Belstead Rd Luther Rd to Stoke Bridge LTP, 2 £969k S106/CIL, DfT 3 13.4 1615 Ipswich Grove Ln to Civic Dr Rope Walk, Tackett St, Dogs LTP, 2 £1163k Head St S106/CIL, DfT 3 13.1 1940 Haverhill Manor Rd Ruffles Rd/Millfields Way junc, LTP, 3 £174k Manor Rd,Eringhausen -

Bury St Edmunds June 2018

June 2018 Bury St Edmunds You said... We did... Community Protection Notice Complaints regarding drug served on residents stopping use causing anti social them having visitors to the behaviour in a residential property. Anti social area. behaviour has now ceased. Responding to issues in your community PCSO Chivers responded to reports of drug dealing taking place in a residential area by carrying out patrols in the area. He identified a suspect who was stopped and found to be in possession of a quantity of controlled drugs. PCSO Howell was approached by a resident living near to a school regarding parking problems at the end of the school day. She liased with the school and identified an area that was more suitable to park. The school advised parents to park in the alternative area which has decreased the parking issue for the resident. Future events Making the community safer The future events that your SNT are Bury ST Edmunds SNT will be taking part in Crucial Crew at the beginning involved in, and will give you an of July 2018. This event is organised to enable young people to learn how to opportunity to chat to them to raise keep themselves safe whilst at home and also when out in the community. your concerns are: PC Fox has taken the role of Community Engagement Officer in Bury St 11/6/18 11:00 am Meet Up Edmunds and will be looking at new ways to engage with the public, this will mondays Boosh Bar include face to face meetings as well as using social networks. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Widening circles in finance, philanthropy and the arts. A study of the life of John Julius Angerstein 1735-1823 Twist, A.F. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Twist, A. F. (2002). Widening circles in finance, philanthropy and the arts. A study of the life of John Julius Angerstein 1735-1823. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 INDEX ABBOT, CHARLES (later LORD COLCHESTER) 81, 82, 172 ABDY. LADY ANNE (nee WELLESLEY) 169 ABDY, SR WILLIAM 169 ABERCORN, LORD 55 ABERDEEN, LORD 157 ABRAHAMAND ISAAC APPROACHING THE PLACEOFSACRIFICE (G. DUGHET/POUSSIN) 93. 136 ABRAMS, ELIZA 108 ABRAMS, HARRIETT 108 ABRAMS, THEODOSIA 108 ABRANTES, DUCHESSE d' 3 ADDINGTON, HENRY 80, 112, 163 ADORATION OF THE SHEPHERDS (REMBRANDT) 95, 156, 157 ALBANO 95 ALEXANDER I, CZAR 6, 120, 142, 176, 178, 179. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 03/07/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/20/0714/OUT Outline Planning Application (Means of Street Farm DECISION: Access to be considered) - 4no. dwellings Low Street Refuse Application and associated garages Bardwell DECISION TYPE: IP31 1AR Delegated APPLICANT: Mr J Webber - RR Webber & ISSUED DATED: Son 1 Jul 2020 WARD: Bardwell AGENT: Mr D Rogers-ALA Ltd PARISH: Bardwell DC/20/0692/HH Householder Planning Application - Single 8 Bury Road DECISION: storey rear extension (previous application Barrow Approve Application DC/17/2643/HH) IP29 5DE DECISION TYPE: Delegated APPLICANT: Mr Michael Sparkes ISSUED DATED: 1 Jul 2020 WARD: Barrow PARISH: Barrow Cum Denham DC/20/0823/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - Barton Hall DECISION: 1no. Beech (T001 on plan) fell The Street No Objections Barton Mills DECISION TYPE: APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs John Hughes Suffolk Delegated IP28 6AW ISSUED DATED: AGENT: Miss Naomi Hull - Temple Property 1 Jul 2020 And Construction WARD: Manor PARISH: Barton Mills DC/20/0835/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - The Dhoon DECISION: 1no. Cherry (T1 on plan) reduce in height 19 The Street No Objections by up to 3 metres and reduce lateral Barton Mills DECISION TYPE: spread by up to 2 metres IP28 6AA Delegated ISSUED DATED: APPLICANT: Cottrell 1 Jul 2020 WARD: Manor AGENT: Mr Luke Wickens PARISH: Barton Mills Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/20/0620/FUL Planning Application - 1no. -

Minutes for October 2019 (Pdf)

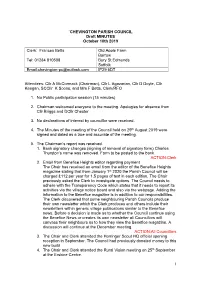

`CHEVINGTON PARISH COUNCIL Draft MINUTES October 10th 2019 Clerk: Frances Betts Old Apple Farm Barrow Tel: 01284 810508 Bury St Edmunds Suffolk Email:[email protected] IP29 5DT Attendees: Cllr A McCormack (Chairman), Cllr L Agazarian, Cllr D Doyle, Cllr Keegan, SCCllr K Soons, and Mrs F Betts, Clerk/RFO 1. No Public participation session (15 minutes) 2. Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting. Apologies for absence from Cllr Briggs and DCllr Chester 3. No declarations of interest by councillor were received. 4. The Minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 29th August 2019 were signed and dated as a true and accurate of the meeting. 5. The Chairman’s report was received. 1. Bank signatory changes (signing of removal of signatory form) Charles Thurston’s name was removed. Form to be posted to the bank. ACTION:Clerk 2. Email from Benefice Heights editor regarding payment The Chair has received an email from the editor of the Benefice Heights magazine stating that from January 1st 2020 the Parish Council will be charged £112 per year for 1.5 pages of text in each edition. The Chair previously asked the Clerk to investigate options. The Council needs to adhere with the Transparency Code which states that it needs to report its activities via the village notice board and also via the webpage. Adding the information to the Benefice magazine is in addition to our responsibilities. The Clerk discovered that some neighbouring Parish Councils produce their own newsletter which the Clerk produces and others include their newsletters within generic village publications similar to the Benefice news. -

WEST Primary Mental Health Workers Schools

West Suffolk Primary Mental Health Workers for Children and Young People: May 2019 The PMHW Service should be contacted when a professional requires advice or consultation on the needs of a child or young person who is displaying mild to moderate mental health symptoms with low levels of risk. If the child or young person’s mental health symptoms are more acute and carry greater risks then they need to see their GP, seek urgent medical advice or refer to the Emotional Wellbeing Hub on 03456002090.The Emotional Wellbeing Hub offers telephone advice in addition to being a referral point from 0-25 years • PMHWs can be contacted during weekdays .If you know which PMHW you wish to speak to or just want to speak to the Duty worker ,you can ring 01284 741600 and ask to speak to the PMHW. • Primary Mental Health Workers cover different geographical areas and offer consultations to high schools and primary schools • As part of our service ,we offer guided self help through our Childrens Wellbeing Practitioners ,Aps • We want to support schools in the most effective way .Please contact us on the above numbers if you would like to discuss regular consultation support for your school. • If we have inadvertently omitted your school or surgery from our list below , please let us know on 01284 741600 PMHW Surgeries Education Establishment (Colleges, Academies, Upper and Primary Schools) Haverhill Castle Manor Academy Tanya Newman Clare Surgeries Samuel Ward Academy Haverhill Surgeries Burton End CP School Wickambrook Surgeries Clements CP School New -

Bury St Edmunds May 2018

May 2018 BURY ST EDMUNDS RESPOND INSPECTOR MATT DEE Police in Bury St Edmunds are currently investigating a series of Exposure offences that have taken place in the area of Moreton Hall. Offences have occurred on the 29th March, 22nd April, 3rd May and 6th May in the late afternoon. The offender is sometimes using a black and white bike and is described as either mixed race or tanned skinned male, aged late 20's to early 30's and short dark brown hair. Any witnesses or anyone with information are urged to come forward. MAKING YOUR COMMUNITY SAFER The SNT have attended a number of initiatives over the past month giving crime prevention advice and reassurance at different venues. PCSO Pooley attended a Fraud awareness day at Barclays bank, offering advice on keeping your bank account and personal finances safe. PCSO Howell attended Beetons Lodge, offering advice on personal safety and security. PCSO Chivers attended the first 'Meet up Monday' event at The Boosch Bar, a new initiative set up to lend a friendly ear to anyone FUTURE EVENTS vulnerable, lonely or even new to the area. The future events that your SNT are involved in, and will give you an opportunity to chat to them to raise your concerns are: PREVENTING, REDUCING AND SOLVING CRIME AND ASB 9th May - Great Whelnetham Parish PC Fox has investigated a series of three theft of peddle cycles meeting that were left insecure outside one of our town Upper schools. 10th May - Fornahm St Martin Parish Having reviewed the CCTV, the suspects were identified and meeting 13th May - South Suffolk Show offenders have all been caught. -

Bury St Edmunds Branch

ACCESSIONS 1 OCTOBER 2000 – 31 MARCH 2002 BURY ST EDMUNDS BRANCH OFFICIAL Babergh District Council: minutes 1973-1985; reports 1973-1989 (EH502) LOCAL PUBLIC West Suffolk Advisory Committee on General Commissioners of Income Tax: minutes, correspondence and miscellaneous papers 1960-1973 (IS500) West Suffolk Hospital, Bury St Edmunds: operation book 1902-1930 (ID503) Walnut Tree Hospital, Sudbury: Sudbury Poor Law Institution/Walnut Tree Hospital: notice of illness volume 1929; notice of death volume 1931; bowel book c1930; head check book 1932-1938; head scurf book 1934; inmates’ clothing volume 1932; maternity (laying in ward) report books 1933, 1936; male infirmary report book 1934; female infirmary report books 1934, 1938; registers of patients 1950-1964; patient day registers 1952-1961; admission and discharge book 1953-1955; Road Traffic Act claims registers 1955-1968; cash book 1964-1975; wages books 1982- 1986 (ID502) SCHOOLS see also SOCIETIES AND ORGANISATIONS, PHOTOGRAPHS AND ILLUSTRATIONS, MISCELLANEOUS Rickinghall VCP School: admission register 1924-1994 (ADB540) Risby CEVCP School: reports of head teacher to school managers/governors 1974- 1992 (ADB524) Sudbury Grammar School: magazines 1926-1974 (HD2531) Whatfield VCP School: managers’ minutes 1903-1973 (ADB702) CIVIL PARISH see also MISCELLANEOUS Great Barton: minutes 1956-1994 (EG527) Hopton-cum-Knettishall: minutes 1920-1991; accounts 1930-1975; burial fees accounts 1934-1978 (EG715) Ixworth and Ixworth Thorpe: minutes 1953-1994; accounts 1975-1985; register of public -

The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology

THE SUFFOLKINSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY: ITS LIFE, TIMESANDMEMBERS by STEVENJ. PLUNKETT The one remains —the many change and pass' (Shelley) 1: ROOTS THE SUFFOLKINSTITUTE of Archaeology and History had its birth 150 years ago, in the spring of 1848, under the title of The Bury and West Suffolk Archaeological Institute. It is among the earliest of the County Societies, preceded only by Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire (1844), Norfolk (1846), and the Cambrian, Bedfordshire, Sussex and Buckinghamshire Societies (1847), and contemporary with those of Lancashire and Cheshire. Others, equally successful, followed, and it is a testimony to the social and intellectual timeliness of these foundations that most still flourish and produce Proceedingsdespite a century and a half of changing approaches to the historical and antiquarian materials for the study of which they were created. The immediate impetus to this movement was the formation in December 1843 of the British ArchaeologicalAssociationfor the Encouragementand Preservationof Researchesinto the Arts ancl Monumentsof theEarly and MiddleAges, which in March 1844 produced the first number of the ArchaeologicalJ ournal.The first published members' list, of 1845, shows the members grouped according to the counties in which they lived, indicating the intention that the Association should gather information from, and disseminate discourses into, the counties through a national forum. The thirty-six founding members from Suffolk form an interesting group from a varied social spectrum, including the collector Edward Acton (Grundisburgh), Francis Capper Brooke (Ufford), John Chevallier Cobbold, Sir Thomas Gery Cullum of Hawstead, David Elisha Davy, William Stevenson Fitch, the Ipswich artists Fred Russel and Wat Hagreen, Professor Henslow, Alfred Suckling, Samuel Tyrnms, John Wodderspoon, the Woodbridge geologist William Whincopp, Richard Almack, and the Revd John Mitford (editor of Gentleman'sMagazine).