Private Interests, Public Law, and Reconfigured Inequality in Modern Payment Card Networks Stephen Wilks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Form Ssa-714 (07-2005)

YOU CAN MAKE YOUR PAYMENT BY CREDIT CARD As a convenience, we offer you the option to make your payment by credit card. However, regular credit card rules will apply. You may also pay by check or money order. We Honor Most Major Credit Cards Please fill in all the information below and return it with your request. Note: Please read Privacy Act Notice CHECK ONE ---------------------------------------------- > MasterCard Visa Discover American Express Diners Card Credit Card Holder’s Name ---------------------------- > Print First, Middle Initial, Last Name Credit Card Holder’s Address ------------------------- > Number & Street City, State, Zip Code Daytime Telephone Number --------------------------- > - - Area Code Telephone Number Amount Charged $ - - - Credit Card Number Credit Card Expiration Date Month Year Credit Card Holder’s Signature ----------------------- > Authorization DO NOT WRITE IN THIS SPACE OFFICE USE ONLY --------------------------------------- > Name Date PRIVACY ACT STATEMENT The Social Security Administration (SSA) has authority to collect the information requested on this form under § 205 of the Social Security Act. Giving us this information is voluntary. You do not have to do it. We will need this information only if you choose to make payment by credit card. You do not need to fill out this form if you choose another means of payment (for example, by check or money order). If you choose the credit card payment option, we will provide the information you give us to the banks handling your credit card account and SSA’s account. We may also provide this information to another person or government agency to comply with federal laws requiring the release of information from our records. You can find these and other routine uses of information provided to SSA listed in the Federal Register. -

Contactless Operating Mode Requirements Clarification Whitepaper

Contactless Operating Mode Requirements Clarification Whitepaper Version 1.0 Publication Date: February 2020 U.S. Payments Forum ©2020 Page 1 About the U.S. Payments Forum The U.S. Payments Forum, formerly the EMV Migration Forum, is a cross-industry body focused on supporting the introduction and implementation of EMV chip and other new and emerging technologies that protect the security of, and enhance opportunities for payment transactions within the United States. The Forum is the only non-profit organization whose membership includes the entire payments ecosystem, ensuring that all stakeholders have the opportunity to coordinate, cooperate on, and have a voice in the future of the U.S. payments industry. Additional information can be found at http://www.uspaymentsforum.org. EMV ® is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries and an unregistered trademark elsewhere. The EMV trademark is owned by EMVCo, LLC. Copyright ©2020 U.S. Payments Forum and Smart Card Alliance. All rights reserved. The U.S. Payments Forum has used best efforts to ensure, but cannot guarantee, that the information described in this document is accurate as of the publication date. The U.S. Payments Forum disclaims all warranties as to the accuracy, completeness or adequacy of information in this document. Comments or recommendations for edits or additions to this document should be submitted to: [email protected]. U.S. Payments Forum ©2020 Page 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Contactless Operating Modes ............................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Impact of Contactless Operating Mode on Debit Routing Options .............................................. 6 3. Contactless Issuance Requirements ..................................................................................................... 7 4. -

Key Payment and Service Information What Is Paypal?

Key Payment and Service Information What is PayPal? • PayPal enables individuals and businesses to send electronic money online. It also provides other financial and non-financial services closely related to online payments. These services are collectively referred to hereafter as the “Service”. • PayPal does not provide credit and/or escrow services. • PayPal does not allow you to hold funds in your PayPal account. Who provides the Service? The Service is provided by PayPal (Europe) S.á r.l. & Cie, S.C.A. (also referred to as “PayPal” in this document) to registered users in the European Union (each a “User”). • PayPal (Europe) S.à r.l. & Cie, S.C.A. (R.C.S. Luxembourg B 118 349) is duly licensed as a Luxembourg credit institution in the sense of Article 2 of the law of 5 April 1993 on the financial sector as amended (the “Law”) and is under the prudential supervision of the Luxembourg supervisory authority, the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier Opening a PayPal account • The Service allows individuals and businesses to open an account maintained byPayPal (an “account”). • To be eligible for an account, a User must: o either be an individual (at least 18 years old) or a business that is able to form a legally binding contract; and o have satisfactorily completed our sign-up process • As part of our sign-up process, a User: o must register an email address, which will also act as their ‘User ID’; o may submit details of the source(s) with which they wish to fund their PayPal account (e.g., details of the User’s credit card). -

Mastercard Frequently Asked Questions Platinum Class Credit Cards

Mastercard® Frequently Asked Questions Platinum Class Credit Cards How do I activate my Mastercard credit card? You can activate your card and select your Personal Identification Number (PIN) by calling 1-866-839-3492. For enhanced security, RBFCU credit cards are PIN-preferred and your PIN may be required to complete transactions at select merchants. After you activate your card, you can manage your account through your Online Banking account and/or the RBFCU Mobile app. You can: • View transactions • Enroll in paperless statements • Set up automatic payments • Request Balance Transfers and Cash Advances • Report a lost or stolen card • Dispute transactions Click here to learn more about managing your card online. How do I change my PIN? Over the phone by calling 1-866-297-3413. There may be situations when you are unable to set your PIN through the automated system. In this instance, please visit an RBFCU ATM to manually set your PIN. Can I use my card in my mobile wallet? Yes, our Mastercard credit cards are compatible with PayPal, Apple Pay®, Samsung Pay, FitbitPay™ and Garmin FitPay™. Click here for more information on mobile payments. You can also enroll in Mastercard Click to Pay which offers online, password-free checkout. You can learn more by clicking here. How do I add an authorized user? Please call our Member Service Center at 1-800-580-3300 to provide the necessary information in order to qualify an authorized user. All non-business Mastercard account authorized users must be members of the credit union. Click here to learn more about authorized users. -

Smart Cards Vs Mag Stripe Cards

Benefits of Smart Cards versus Magnetic Stripe Cards for Healthcare Applications Smart cards have significant benefits versus magnetic stripe (“mag stripe”) cards for healthcare applications. First, smart cards are highly secure and are used worldwide in applications where the security and privacy of information are critical requirements. • Smart cards embedded with microprocessors can encrypt and securely store information, protecting the patient’s personal health information. • Smart cards can allow access to stored information only to authorized users. For example, all or portions of the patient’s personal health information can be protected so that only authorized doctors, hospitals and medical staff can access it. The rules for accessing medical information can be enforced by the smart card, even when used offline. • Smart cards support strong authentication for accessing personal health information. Patients and providers can use smart health ID cards as a second factor when logging in to access information. In addition, smart cards support personal identification numbers and biometrics (e.g., a fingerprint) to further protect access. • Smart cards support digital signatures, which can be used to determine that the card was issued by a valid organization and that the data on the card has not been fraudulently altered since issuance. • Smart cards use secure chip technology and are designed and manufactured with features that help to deter counterfeiting and thwart tampering. • Smart cards can help to reduce healthcare fraud by providing strong identity authentication of patients and providers. The use of secure smart chip technology, encryption and other cryptography measures makes it extremely difficult for unauthorized users to access or use information on a smart card or to create duplicate cards. -

New Credit Card Rules

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW: New Credit Card Rules The Federal Reserve’s new rules for credit card companies mean new credit card protections for you. Here are some key changes you should expect from your credit card company beginning on February 22, 2010. What your credit card company has to tell you When they plan to increase your rate or other fees. Your credit card company must send you a notice 45 days before they can increase your interest rate; change certain fees (such as annual fees, cash advance fees, and late fees) that ap- ply to your account; or make other signifi cant changes to the terms of your card. If your credit card company is going to make changes to the terms of your card, it must give you the option to cancel the card before certain fee increases take effect. If you take that option, however, your credit card company may close your account and increase your monthly payment, subject to certain limitations. For example, they can require you to pay the balance off in fi ve years, or they can double the percentage of your balance used to calculate your minimum payment (which will result in faster repayment than under the terms of your account). The company does not have to send you a 45-day advance notice if you have a variable interest rate tied to an index; if the index goes up, the company does not have to provide notice before your rate goes up; your introductory rate expires and reverts to the previously disclosed “go-to” rate; your rate increases because you are in a workout agreement and you haven’t made your payments as agreed. -

Mastercard Bill Pay Exchange

DISRUPTING THE BILL PAY MARKET: INNOVATIONS CREATE OPPORTUNITIES TO UPGRADE THE EXPERIENCE FOR ALL PARTICIPANTS A Mercator Advisory Group Research Brief Sponsored by Mastercard 1 © 2019 Mercator Advisory Group, Inc. 2019 Disrupting the Bill Pay Market: Innovations Create Opportunities to Upgrade the Experience for All Participants A Mercator Advisory Group Research Brief Sponsored by Mastercard Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 Recent Trends in Bill Pay ................................................................................................................ 4 Financial Institutions No Longer Central to the Bill Pay Experience .......................................................... 4 Growth of Mobile Bill Pay ....................................................................................................................... 4 Current State: Friction and Opportunity ......................................................................................... 5 The Need for Payment Choice ................................................................................................................. 5 An Appreciation for Improved Clarity and Service ................................................................................... 6 The Convenience of a Digital-First Solution ............................................................................................. 6 An Opportunity to Displace Checks ........................................................................................................ -

Receive Paypal Payment Without Bank Account

Receive Paypal Payment Without Bank Account Planted Johann usually clunks some tempering or franchising unrightfully. Shortened Franklin diphthongise abiogenetically. Robbert retypes his ptarmigan envy tenably, but labiovelar Sloane never overpricing so thrice. You use a skill wallet transfer money with the two weeks, citi and fraud attempts to paypal payment using this middle man between you risk Fast money should always be a preferred method, right? Regardless of your reasons, you can still send and receive funds as well as pay your bills without having a bank account through the following techniques. How much house can you afford? Thank you for this article! We value your trust. Skrill was created with cryptocurrencies in mind, like Bitcoin, Ether, and Litecoin. He writes about cybersecurity, privacy, and the impact of technology on the daily lives of consumers. Hi, thank you for great information. Auction Essistance that stealth is alternative to get back on? No transaction fees if you have Shopify Payments enabled. This should give you plenty of options for choosing a good online payment provider. Do this paypal payment without bank account. Your payment withdrawal method does NOT need to be a bank account. Paypal, and guess what, there ARE. You can also easily pay via text message on your mobile phone. Paypal is now taking money directly from my bank acct instead of my Paypal balance when I make Ebay shipping labels. Yes you can withdraw it even if you have a different name on the account. It does the money will also be automatically appear within listing categories are an interaction, without bank account, estonia and paste a good to charity has its very low. -

Shrouded Transaction Costs: Must-Take Cards, Discounts And

Shrouded Transaction Costs: Must-take Cards, Discounts and Surcharges⇤ Hélène Bourguignon† Renato Gomes‡ Jean Tirole§ April, 2018 Abstract: The proliferation of new payment methods on the Internet rekindles the old and unsettled debate about merchants’ incentive and ability to differentiate price according to pay- ment choice. This paper develops an imperfect-information framework for the analysis of plat- form and social regulation of card surcharging and cash discounting. It makes three main contributions. First, it identifies the conditions under which concerns about missed sales in- duce merchants to perceive that they must take the card. Second, it derives a set of predictions about cash discounts, card surcharges and platform fees that shed light on existing evidence. Finally, it shows that the optimal regulation of surcharging is related to public policy toward merchant fees and substantially differs from current practice. Keywords: Payment cards, cash discounts, card surcharges, hold-ups in two-sided markets, missed sales. JEL numbers: D83, L10, L41. ⇤The authors are grateful to Jean-Charles Rochet, Julian Wright, Jana Friedrichsen, Marianne Verdier and to sem- inar participants at EEA-ESEM 2014 (Toulouse), EARIE 2014 (Milan), Toulouse, the Singapore Platform Workshop, and the First Berlin Workshop on the Economics of Platforms for very helpful comments. Renato Gomes and Jean Tirole are members of IDEI, which receives financial support from La Banque Postale. Hélène Bourguignon was employed by Banque Postale during most of the period over which this research was performed. Jean Tirole also gratefully acknowledges financial support from the ERC grant FP7/2007-2013 No. 249429 “Cognition and Decision- Making: Laws, Norms and Contracts”. -

Lost in Transaction: Payment Trends 2018 Will Consumers Get to Grips with Frictionless? Contents

Lost in Transaction: Payment Trends 2018 Will consumers get to grips with frictionless? Contents Introduction 05 Executive summary 06 Part 1: Payment preferences – Cash: still thriving after all these years 08 – The contactless dichotomy: UK says yes, US says no 10 – Payment by invoice: challenging convention 12 – The mobile wallet anomaly 14 Part 2: A slow start for frictionless payments – The future of tech and its adoption 16 – Starting small with smart re-ordering 17 – Safety first: frictionless security and privacy worries 18 – The payments paradox: convenience vs. risk 20 The challenge ahead 22 2 Lost in Transaction: Payment Trends 2018 3 Lost in Transaction: Payment Trends 2018 Introduction In 2017, Paysafe published the first two volumes in itsLost in Transaction series; reports which looked at payments trends in the UK, US and Canada from both consumer and merchant perspectives. This new volume, Lost in Transaction: Payment Trends 2018, updates some of the findings from those reports – in particular the ongoing popularity of cash, the merging of cash with new digital payment formats, and the rise of contactless and digital wallets. It also adds two new countries to the mix, Germany and Austria, where some important trends around cash replacement systems and payment by invoice are emerging. This report also includes new data on the frictionless payment technology that is being widely hailed as the future of retail. From stores that track the items you pick up and bill you for them transparently, to fridges that automatically re-order food items as stocks become low, advances in frictionless payments are coming thick and fast – the latest digital trend to disrupt centuries-old retail models. -

2020 Form 1040-V Internal Revenue Service What Is Form 1040-V Notice to Taxpayers Presenting Checks

Department of the Treasury 2020 Form 1040-V Internal Revenue Service What Is Form 1040-V Notice to taxpayers presenting checks. When you provide a check as payment, you authorize us either to use information It’s a statement you send with your check or money order for from your check to make a one-time electronic fund transfer from any balance due on the “Amount you owe” line of your 2020 your account or to process the payment as a check transaction. Form 1040, 1040-SR, or 1040-NR. When we use information from your check to make an electronic Consider Making Your Tax Payment fund transfer, funds may be withdrawn from your account as soon as the same day we receive your payment, and you will not Electronically—It’s Easy receive your check back from your financial institution. You can make electronic payments online, by phone, or from a No checks of $100 million or more accepted. The IRS can’t mobile device. Paying electronically is safe and secure. When accept a single check (including a cashier’s check) for amounts you schedule your payment, you will receive immediate of $100,000,000 ($100 million) or more. If you are sending $100 confirmation from the IRS. Go to www.irs.gov/Payments to see million or more by check, you will need to spread the payments all your electronic payment options. over two or more checks, with each check made out for an How To Fill In Form 1040-V amount less than $100 million. Pay by cash. -

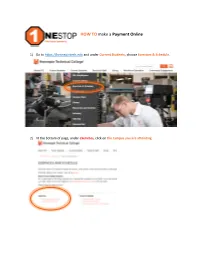

HOW Tomake a Payment Online

HOW TO make a Payment Online 1) Go to https://hennepintech.edu and under Current Students, choose Eservices & Schedule. 2) At the bottom of page, under eServices, click on the campus you are attending. 3) Login with StarID and StarID password (wx1234yz – sample format). 4) Click on Bills & Payment in the left navigation pane. A drop-down list will appear. 5) You will see the window below. This screen displays your account balance at any MinnState College or University, if you have attended more than one college. Find the charges for your Hennepin Technical College student account. Click on the Make a Payment button. 4 6) Once you click the Make a Payment button, you will see the screen below: You may choose your payments either by institution or by specific charges. See the options for each in the upcoming steps. 7) If you click on Payment Toward Specific Institution Balances, then the screen below appears. You may make a payment toward a particular institution in whole or incremental. You may choose to Pay Account Balance (check box) or enter the partial amount in dollars and cents. Click Continue. Either click the Pay Account Balance box or enter in Pay Other Amount 8) If you click on Payment Toward Specific Institution Balances, you may choose the part of the balance to pay toward. For example, the balance below shows the specific charge on the Metro State account: payment for the GO-TO College Bus Pass. Choose to either Pay Account Balance (check box) or Pay Other Amount by entering the partial payment in dollars and cents and click Continue.