Letter from Associate Attorney General Gupta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

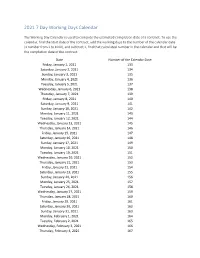

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

Pay Week Begin: Saturdays Pay Week End: Fridays Check Date

Pay Week Begin: Pay Week End: Due to UCP no later Check Date: Saturdays Fridays than Monday 7:30am week 1 December 10, 2016 December 16, 2016 December 19, 2016 December 30, 2016 week 2 December 17, 2016 December 23, 2016 December 26, 2016 week 1 December 24, 2016 December 30, 2016 January 2, 2017 January 13, 2017 week 2 December 31, 2016 January 6, 2017 January 9, 2017 week 1 January 7, 2017 January 13, 2017 January 16, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 2 January 14, 2017 January 20, 2017 January 23, 2017 January 21, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 1 January 30, 2017 February 10, 2017 week 2 January 28, 2017 February 3, 2017 February 6, 2017 week 1 February 4, 2017 February 10, 2017 February 13, 2017 February 24, 2017 week 2 February 11, 2017 February 17, 2017 February 20, 2017 March 3, 2017 week 1 February 18, 2017 February 24, 2017 February 27, 2017 ***1 Week Pay Period Transition*** week 1 February 25, 2017 March 3, 2017 March 6, 2017 March 17, 2017 week 2 March 4, 2017 March 10, 2017 March 13, 2017 week 1 March 11, 2017 March 17, 2017 March 20, 2017 March 31, 2017 week 2 March 18, 2017 March 24, 2017 March 27, 2017 week 1 March 25, 2017 March 31, 2017 April 3, 2017 April 14, 2017 week 2 April 1, 2017 April 7, 2017 April 10, 2017 week 1 April 8, 2017 April 14, 2017 April 17, 2017 April 28, 2017 week 2 April 15, 2017 April 21, 2017 April 24, 2017 week 1 April 22, 2017 April 28, 2017 May 1, 2017 May 12, 2017 week 2 April 29, 2017 May 5, 2017 May 8, 2017 week 1 May 6, 2017 May 12, 2017 May 15, 2017 May 26, 2017 week 2 May 13, 2017 May 19, 2017 May -

June 24 Special Meeting

PAGE NO: 1300 MEETING NO. 21 SPECIAL MEETING JUNE 24, 2021 Jessica Wright, President of the Board, called the Special Meeting of the Stow-Munroe Falls Board of Education to order at 5:00 p.m. on June 24, 2021. The meeting was held at Stow-Munroe Falls Board of Education Office. President Wright led with the Pledge of Allegiance. MEMBERS PRESENT – Gerry Bettio, Nancy Brown, Lisa Johnson-Bowers, and Jessica Wright MEMBERS ABSENT – Jason Whitacre 144-21 ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA It was moved by Bettio, seconded by Johnson-Bowers, that the Stow-Munroe Falls City School District Board of Education adopt the agenda for June 24, 2021. ON ROLL CALL "AYES" – Bettio, Brown, Johnson-Bowers, and Wright "NAYS" – None Motion Carried 145-21 TREASURER’S RECOMMENDATION I WISH TO RECOMMEND that the Board of Education approve the Master Agreement between the Stow-Munroe Falls Classified Employees’ Association/OEA/NEA and the Stow-Munroe Falls City School District Board of Education for an agreement with a duration of July 1, 2021-June 30, 2022. It was moved by Brown, seconded by Bettio, that the Board of Education approve the Master Agreement between the Stow-Munroe Falls Classified Employees’ Association/OEA/NEA and the Stow-Munroe Falls City School District Board of Education for an agreement with a duration of July 1, 2021-June 30, 2022. ON ROLL CALL "AYES" – Bettio, Brown, Johnson-Bowers and Wright "NAYS" – None 146-21 EXECUTIVE SESSION For the purpose of preparing considering the employment of a public employee. It was motioned by Brown, seconded by Johnson-Bowers, that the Board of Education enter into Executive Session at 5:03 p.m. -

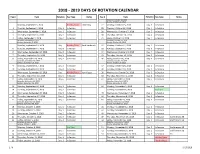

2018 - 2019 Days of Rotation Calendar

2018 - 2019 DAYS OF ROTATION CALENDAR Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Saturday, October 13, 2018 Sunday, October 14, 2018 Monday, September 3, 2018 Holiday/Vaca Labor Day 27 Monday, October 15, 2018 Day 3 In Session 1 Tuesday, September 4, 2018 Day 1 In Session 28 Tuesday, October 16, 2018 Day 4 In Session 2 Wednesday, September 5, 2018 Day 2 In Session 29 Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Day 5 In Session 3 Thursday, September 6, 2018 Day 3 In Session 30 Thursday, October 18, 2018 Day 6 In Session 4 Friday, September 7, 2018 Day 4 In Session 31 Friday, October 19, 2018 Day 1 In Session Saturday, September 8, 2018 Saturday, October 20, 2018 Sunday, September 9, 2018 Sunday, October 21, 2018 Monday, September 10, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Rosh Hashanah 32 Monday, October 22, 2018 Day 2 In Session 5 Tuesday, September 11, 2018 Day 5 In Session 33 Tuesday, October 23, 2018 Day 3 In Session 6 Wednesday, September 12, 2018 Day 6 In Session 34 Wednesday, October 24, 2018 Day 4 In Session 7 Thursday, September 13, 2018 Day 1 In Session 35 Thursday, October 25, 2018 Day 5 In Session 8 Friday, September 14, 2018 Day 2 In Session 36 Friday, October 26, 2018 Day 6 In Session Saturday, September 15, 2018 Saturday, October 27, 2018 Sunday, September 16, 2018 Sunday, October 28, 2018 9 Monday, September 17, 2018 Day 3 In Session 37 Monday, October 29, 2018 Day 1 In Session 10 Tuesday, September 18, 2018 Day 4 In Session 38 Tuesday, October 30, 2018 Day 2 In Session Wednesday, September 19, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Yom Kippur 39 Wednesday, October 31, 2018 Day 3 In Session 11 Thursday, September 20, 2018 Day 5 In Session 40 Thursday, November 1, 2018 Day 4 In Session 12 Friday, September 21, 2018 Day 6 In Session 41 Friday, November 2, 2018 Day 5 In Session Saturday, September 22, 2018 Saturday, November 3, 2018 Sunday, September 23, 2018 Sunday, November 4, 2018 13 Monday, September 24, 2018 Day 1 In Session 42 Monday, November 5, 2018 Day 6 In Session 14 Tuesday, September 25, 2018 Day 2 In Session Tuesday, November 6, 2018 Prof Dev. -

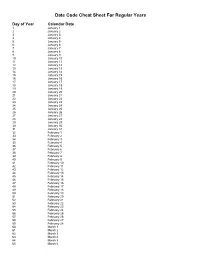

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

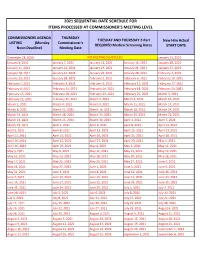

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

BULLETIN June 24, 2021, Meeting

BULLETIN June 24, 2021, Meeting Presiding: President Robert started the meeting at 7:00am. President Robert was at the Graffiti USA Classic Car Museum along with a group of in-person Kiwanians and a zoom feed with additional members from near and far was also in progress.. The meeting started with a robust ringing of the bell. An opening song was directed by Gary Goodman, the pledge allegiance to the flag was directed by Dirk Paintedman and a prayer was delivered by Marty Villa. Guests: Linda Ridenour from the R club. Marty Villa’s grandson, and wife Ruth. Key Club Secretaries Selena Little, Adrienne Sabado. Announcements: July 7 Graffiti Car Show registration will begin. Marty Villa-Tomorrow the first Peace Path painting will take place. The school is at 1900 Kirschen Drive, Modesto. Adrian said NMK elections are coming up soon. First reading of nominees was made. The new officers will be installed September 17. President Aron Kellum, Vice President Jenifer Mullen, 2nd VP Ana Kanbara. PO Box 473, Modesto, CA 95353 website: NorthModestoKiwanis.org Jeremiah Williams said July 4 celebration will take place at John Thurman field with fireworks. Ken Darby-Fresno interclub July 27, high noon at the Big Bear Dinner 3600 W. Shaw Ave Fresno, CA 93711. Randy Cook-The Blazing Saddles Chili Cook Off is this Saturday, June 26 at Randy, and Denise’s man cave/she shed. Chili Cooks should arrive at 5 pm to draw numbers for position and set up their cooking station. Each cook will have a table that can be decked out to highlight their “brand”. -

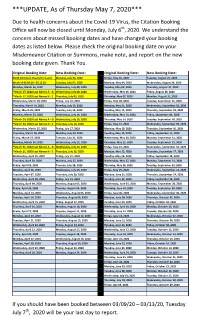

UPDATE, As of Thursday May 7, 2020***

***UPDATE, As of Thursday May 7, 2020*** Due to health concerns about the Covid-19 Virus, the Citation Booking Office will now be closed until Monday, July 6th, 2020. We understand the concern about missed booking dates and have changed your booking dates as listed below. Please check the original booking date on your Misdemeanor Citation or Summons, make note, and report on the new booking date given. Thank You. Original Booking Date: New Booking Date: Original Booking Date: New Booking Date: 03.03.20 (Court Closed/Tornado) Monday, July 06, 2020 42 Friday, May 01, 2020 Tuesday, August 25, 2020 Week of 03.09.20 - 03.13.20 Tuesday, July 07, 2020 82 Monday, May 04, 2020 Wednesday, August 26, 2020 Monday, March 16, 2020 Wednesday, July 08, 2020 67 Tuesday, May 05, 2020 Thursday, August 27, 2020 *March 17, 2020 Last Names A - G Wednesday, July 08, 2020 ^ Wednesday, May 06, 2020 Friday, August 28, 2020 *March 17, 2020 Last Names H - Z Thursday, July 09, 2020 72 Thursday, May 07, 2020 Monday, August 31, 2020 Wednesday, March 18, 2020 Friday, July 10, 2020 54 Friday, May 08, 2020 Tuesday, September 01, 2020 Thursday, March 19, 2020 Monday, July 13, 2020 36 Monday, May 11, 2020 Wednesday, September 02, 2020 Friday, March 20, 2020 Tuesday, July 14, 2020 52 Tuesday, May 12, 2020 Thursday, September 03, 2020 Monday, March 23, 2020 Wednesday, July 15, 2020 70 Wednesday, May 13, 2020 Friday, September 04, 2020 *March 24, 2020 Last Names A - G Wednesday, July 15, 2020 ^ Thursday, May 14, 2020 Tuesday, September 08, 2020 *March 24, 2020 Last Names H -

Compliance and Reporting Guidance

June 24, 2021 Version: 1.1 Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Guidance on Recipient Compliance and Reporting Responsibilities On March 11, 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act was signed into law, and established the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund and Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, which together make up the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“SLFRF”) program. This program is intended to provide support to State, territorial, local, and Tribal governments in responding to the economic and public health impacts of COVID-19 and in their efforts to contain impacts on their communities, residents, and businesses. This guidance provides additional detail and clarification for each recipient’s compliance and reporting responsibilities under the SLFRF program, and should be read in concert with the Award Terms and Conditions, the authorizing statute, the SLFRF implementing regulation, and other regulatory and statutory requirements, including regulatory requirements under the Uniform Guidance (2 CRF Part 200). Please see the Assistance Listing in SAM.gov under assistance listing number (formerly known as CFDA number), 21.027 for more information. Please Note: This guidance document applies to the SLFRF program only and does not change nor impact reporting and compliance requirements for the Coronavirus Relief Fund (“CRF”) established by the CARES Act. This guidance includes two parts: Part 1: General Guidance This section provides an orientation to recipients’ compliance responsibilities and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) expectations and recommends best practices where appropriate under the SLFRF Program. A. Key Principles……………………..……………………………………………………. P. 3 B. Statutory Eligible Uses…………………………………………………………………. P. 3 C. -

Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 121/Wednesday, June 24, 2015

Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 121 / Wednesday, June 24, 2015 / Notices 36319 lead to continuation or recurrence of net recurrence of material injury to an recurrence of dumping or countervailable subsides. The industry in the United States within a countervailable subsidies, and material International Trade Commission (ITC) reasonably foreseeable time.4 injury to an industry in the United also determined that revocation of these States, pursuant to sections 751(c) and Scope of the Orders AD and CVD orders would likely lead 751(d)(2) of the Act, the Department to continuation or recurrence of material The scope of the orders include all hereby orders the continuation of the injury to an industry in the United grades and granulation sizes of citric AD orders on citric acid from Canada States. Therefore, the Department is acid, sodium citrate, and potassium and the PRC and the CVD order on citric publishing this notice of continuation of citrate in their unblended forms, acid from the PRC. U.S. Customs and these AD and CVD orders. whether dry or in solution, and Border Protection (CBP) will continue to DATES: Effective Date: June 24, 2015. regardless of packaging type. The scope collect AD and CVD cash deposits at the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: also includes blends of citric acid, rates in effect at the time of entry for all Katherine Johnson (Canada AD Order), sodium citrate, and potassium citrate; as imports of subject merchandise. AD/CVD Operations, Office II; Krisha well as blends with other ingredients, The effective date of the continuation Hill (PRC AD Order), AD/CVD such as sugar, where the unblended of these orders will be the date of Operations, Office IV; or Elizabeth form(s) of citric acid, sodium citrate, publication in the Federal Register of Eastwood (PRC CVD Order), AD/CVD and potassium citrate constitute 40 this notice of continuation.