Broad-Cheeked Hopping Mouse)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dusky Hopping Mouse

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory DUSKY HOPPING-MOUSE Notomys fuscus Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Endangered Photo: P. Canty Description as Ooldea in South Australia and east to the Victoria/New South Wales borders. The dusky hopping-mouse is characterized by its strong incisor teeth, long tail, large ears, The species has not been recorded in the dark eyes, and extremely lengthened and Northern Territory since 1939 when it was narrow hind feet, which have only four pads collected in sand dunes on Maryvale Station on the sole. The head-body length is 91-177 and on Andado Station. An earlier record is mm, tail length is 125-225 mm, and body from Charlotte Waters. weight is about 20-50 g. Coloration of the Conservation reserves where reported: upper parts varies from pale sandy brown to None. yellowish brown to ashy brown or greyish. The underparts of dusky hopping-mice are white. The fur is fine, close and soft. Long hairs near the tip of the tail give the effect of a brush. The dusky hopping-mouse has a well- developed glandular area on the underside of its neck or chest. Females have four nipples. Distribution The current distribution of the dusky hopping-mouse appears to be restricted to the eastern Lake Eyre Basin within the Known locations of the dusky hopping-mouse Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields bioregion in (ο = pre 1970). South Australia and Queensland. An intensive survey in the 1990s located populations at Ecology eight locations in the Strzelecki Desert and adjacent Cobbler Sandhills (South Australia) The dusky hopping-mouse occupies a variety and in south-west Queensland (Moseby et al. -

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Management of the Terrestrial Small Mammal and Lizard Communities in the Dune System Of

Management of the terrestrial small mammal and lizard communities in the dune system of Sturt National Park, Australia: Historic and contemporary effects of pastoralism and fox predation Ulrike Sabine Klöcker (Dipl. – Biol., Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn, Germany) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2009 Abstract This thesis addressed three issues related to the management and conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates in the arid zone. The study site was an amalgamation of pastoral properties forming the now protected area of Sturt National Park in far-western New South Wales, Australia. Thus firstly, it assessed recovery from disturbance accrued through more than a century of Sheep grazing. Vegetation parameters, Fox, Cat and Rabbit abundance, and the small vertebrate communities were compared, with distance to watering points used as a surrogate for grazing intensity. Secondly, the impacts of small-scale but intensive combined Fox and Rabbit control on small vertebrates were investigated. Thirdly, the ecology of the rare Dusky Hopping Mouse (Notomys fuscus) was used as an exemplar to illustrate and discuss some of the complexities related to the conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates, with a particular focus on desert rodents. Thirty-five years after the removal of livestock and the closure of watering points, areas that were historically heavily disturbed are now nearly indistinguishable from nearby relatively undisturbed areas, despite uncontrolled native herbivore (kangaroo) abundance. Rainfall patterns, rather than grazing history, were responsible for the observed variation between individual sites and may overlay potential residual grazing effects. -

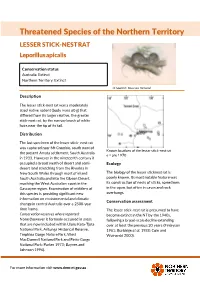

LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus Apicalis

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus apicalis Conservation status Australia: Extinct Northern Territory: Extinct (J Gould © Museum Victoria) Description The lesser stick-nest rat was a moderately sized native rodent (body mass 60 g) that differed from its larger relative, the greater stick-nest rat, by the narrow brush of white hairs near the tip of its tail. Distribution The last specimen of the lesser stick- nest rat was captured near Mt Crombie, south west of Known locations of the lesser stick-nest rat the present Amata settlement, South Australia ο = pre 1970 in 1933. However in the nineteenth century it occupied a broad swath of desert and semi- Ecology desert land stretching from the Riverina in New South Wales through most of inland The biology of the lesser sticknest rat is South Australia and into the Gibson Desert, poorly known. Its most notable feature was reaching the West Australian coast in the its construction of nests of sticks, sometimes Gascoyne region. Examination of middens of in the open, but often in caves and rock this species is providing significant new overhangs. information on environmental and climatic Conservation assessment change in central Australia over a 2500-year time frame. The lesser stick-nest rat is presumed to have Conservation reserves where reported: become extinct in the NT by the 1940s, None (however it formerly occurred in areas following a broad-scale decline extending that are now included within Uluru Kata-Tjuta over at least the previous 30 years (Finlayson National Park, Arltunga Historical Reserve, 1961; Burbidge et al. -

Reintroducing the Dingo: the Risk of Dingo Predation to Threatened Vertebrates of Western New South Wales

CSIRO PUBLISHING Wildlife Research http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WR11128 Reintroducing the dingo: the risk of dingo predation to threatened vertebrates of western New South Wales B. L. Allen A,C and P. J. S. Fleming B AThe University of Queensland, School of Animal Studies, Gatton, Qld 4343, Australia. BVertebrate Pest Research Unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange Agricultural Institute, Forest Road, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. CCorresponding author. Present address: Vertebrate Pest Research Unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Sulfide Street, Broken Hill, NSW 2880, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract Context. The reintroduction of dingoes into sheep-grazing areas south-east of the dingo barrier fence has been suggested as a mechanism to suppress fox and feral-cat impacts. Using the Western Division of New South Wales as a case study, Dickman et al. (2009) recently assessed the risk of fox and cat predation to extant threatened species and concluded that reintroducing dingoes into the area would have positive effects for most of the threatened vertebrates there, aiding their recovery through trophic cascade effects. However, they did not formally assess the risk of dingo predation to the same threatened species. Aims. To assess the risk of dingo predation to the extant and locally extinct threatened vertebrates of western New South Wales using methods amenable to comparison with Dickman et al. (2009). Methods. The predation-risk assessment method used in Dickman et al. (2009) for foxes and cats was applied here to dingoes, with minor modification to accommodate the dietary differences of dingoes. This method is based on six independent biological attributes, primarily reflective of potential vulnerability characteristics of the prey. -

Female Reproductive Suppression in an Australian Arid Zone Rodent, the Spinifex Hopping Mouse K

Journal of Zoology. Print ISSN 0952-8369 Female reproductive suppression in an Australian arid zone rodent, the spinifex hopping mouse K. K. Berris1 , W. G. Breed1 , K. E. Moseby2,3 & S. M. Carthew4 1School of Biological Sciences,The University of Adelaide,Adelaide,SA,Australia 2Centre for Ecosystem Science,University of New South Wales,Sydney,NSW,Australia 3Arid Recovery,Roxby Downs,SA,Australia 4Research Institute for Environment and Livelihoods,Charles Darwin University,Casuarina,NT,Australia Keywords Abstract Australia; Muridae; rodent; exotic predators; reproductive suppression; population density; arid The spinifex hopping mouse (Notomys alexis) is an Australian arid zone rodent that environments; Notomys alexis. undergoes boom and bust population cycles in its natural environment. Most popu- lations studied to date have been sympatric with exotic predators and introduced Correspondence herbivores, likely affecting their population dynamics. Therefore, it is unclear Karleah K. Berris, , PO Box 919, Kingscote, SA, whether high-density populations of hopping mice are regulated by purely extrinsic 5223 Australia. factors or whether intrinsic factors are also at play. We hypothesized that reproduc- Email: [email protected] tive suppression of female N. alexis may occur in high-density populations as has been observed in some other rodent species. Reproductive condition of adult Editor: Nigel Bennett female N. alexis was compared between a high-density population within the Arid Recovery reserve, where exotic predators and introduced herbivores are excluded, Received 11 April 2020; revised 2 June 2020; and a low-density population on adjacent pastoral properties (no exclusions). Trap accepted 4 June 2020 success was 10 times higher inside the reserve than at pastoral sites, and no adult females were observed breeding in the reserve population, despite 26 % of females doi:10.1111/jzo.12813 at pastoral sites recorded breeding. -

Terrestrial Native Mammals of Western Australia

TERRESTRIALNATIVE MAMMALS OF WESTERNAUSTRALIA On a number of occasionswe have been asked what D as y ce r cus u ist ica ud q-Mul Aara are the marsupialsof W.A. or what is the scientiflcname Anlechinusfla.t,ipes Matdo given to a palticular animal whosecommon name only A n t ec h i nus ap i ca I i s-Dlbbler rs known. Antechinusr osemondae-Little Red Antechinus As a guide,the following list of62 speciesof marsupials A nteclt itus mqcdonneIlens is-Red-eared Antechi nus and 59 speciesof othersis publishedbelow. Antechinus ? b ilar n i-Halney' s Antechinus Antec h in us mqculatrJ-Pismv Antechinus N ingaui r idei-Ride's Nirfaui - MARSUPALIA Ningauirinealvi Ealev's-KimNinsaui Ptaiigole*fuilissima beiiey Planigale Macropodidae Plani gale tenuirostris-Narrow-nosed Planigate Megaleia rufa Red Kangaroo Smi nt hopsis mu rina-Common Dulnart Macropus robustus-Etro Smin t hop[is longicaudat.t-Long-tailed Dunnart M acr opus fu Ii g inos,s-Western Grey Kangaroo Sminthops is cras sicaudat a-F at-tailed Dunnart Macrcpus antilo nus Antilope Kangaroo S-nint hopsi s froggal//- Larapinla Macropu"^agi /rs Sandy Wallaby Stnintllopsirgranuli,oer -Whire-railed Dunnart Macrcpus rirra Brush Wallaby Sninthopsis hir t ipes-Hairy -footed Dunnart M acro ptrs eugenii-T ammar Sminthopsiso oldea-^f r oughton's Dunnart Set oni x brac ltyuru s-Quokka A ntec h inomys lanrger-Wuhl-Wuhl On y ch oga I ea Lng uife r a-Kar r abul M.yr nte c o b ius fasc ialrls-N umbat Ony c hogalea Iunq ta-W \rrur.g Notoryctidae Lagorchest es conspic i Ilat us,Spectacied Hare-Wallaby Notorlctes -

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys Australis 2012

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis 2012 - 1 - This plan should be cited as follows: Moseby, K. (2012) National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Published by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Adopted under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: [date to be supplied] ISBN : 978-0-9806503-1-0 © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Government of South Australia. Requests and inquiries regarding reproduction should be addressed to: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Note: This recovery plan sets out the actions necessary to stop the decline of, and support the recovery of, the listed threatened species or ecological community. The Australian Government is committed to acting in accordance with the plan and to implementing the plan as it applies to Commonwealth areas. The plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a broad range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Queensland disclaimer: The Australian Government, in partnership with the Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, facilitates the publication of recovery plans to detail the actions needed for the conservation of threatened native wildlife. -

Northern Hopping Mouse Notomys Aquilo

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory NORTHERN HOPPING-MOUSE Notomys aquilo Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Vulnerable Photo: S. Ward Description Conservation reserves where reported: Anindilyakwa (Groote Eylandt) Indigenous The northern hopping-mouse is a small (25- Protected Area and Nanydjaka (Cape Arnhem) 50g) rodent of unmistakable appearance Indigenous Protected Area. within its range. It has an extremely long tail (around 140-150 per cent head-body length) tipped with a tuft of longer dark hairs, large ears and eyes, and very long (35-40mm) narrow hind-feet. It is sandy-brown above and white below. It is the only hopping-mouse in the Top End of the Northern Territory (NT). The spinifex hopping mouse N. alexis extends north to the Barkly Tableland, and is generally of similar morphology. Distribution There are remarkably few documented Known locations of the northern hopping-mouse records of the northern hopping-mouse (Woinarski et al. 1999; Woinarski 2004). In Ecology the NT, it is known from Groote Eylandt and coastal north-eastern Arnhem Land, with The northern hopping-mouse is largely unvouchered records from a few hundred restricted to sandy substrates, particularly kilometres further south, west and inland; and those supporting floristically diverse one specimen from inland central Arnhem heathlands and/or grasslands (Woinarski et al. Land (Dixon and Huxley 1985; Woinarski et 1999). This includes both vegetated dune al. 1999). Beyond the NT, it has also been systems and sandy eucalypt woodlands. It recorded from Cape York Peninsula (one constructs elaborate communally-used specimen with an imprecise locality record burrow systems, whose vertical entrances from the last half of the nineteenth century). -

Why Are Small Mammals Not Such Good Thermoregulators in Arid

Are day-active small mammals rare and small birds abundant in Australian desert environments because small mammals are inferior thermoregulators? P. C. Withers1, C. E. Cooper1,2, and W.A. Buttemer3 1Zoology, School of Animal Biology M092, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009 2Present Address: Centre for Behavioural and Physiological Ecology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351 3 Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522 1 Abstract Small desert birds are typically diurnal and highly mobile (hence conspicuous) whereas small non-volant mammals are generally nocturnal and less mobile (hence inconspicuous). Birds are more mobile than terrestrial mammals on a local and geographic scale, and most desert birds are not endemic but simply move to avoid the extremes of desert conditions. Many small desert mammals are relatively sedentary and regularly use physiological adjustments to cope with their desert environment (e.g. aestivation or hibernation). It seems likely that prey activity patterns and reduced conspicuousness to predators have reinforced nocturnality in small desert mammals. Differences such as nocturnality and mobility simply reflect differing life-history traits of birds and mammals rather than being a direct result of their differences in physiological capacity for tolerating daytime desert conditions. Australian desert mammals and birds Small birds are much more conspicuous in Australian desert environments than small mammals, partly because most birds are diurnal, whereas most mammals are nocturnal. Despite birds having over twice the number of species as mammals (ca. 9600 vs. 4500 species, respectively), the number of bird species confined to desert regions is relatively small, and their speciation and endemism are generally low (Wiens 1991). -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Therya ISSN: 2007-3364 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste Woinarski, John C. Z.; Burbidge, Andrew A.; Harrison, Peter L. A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals Therya, vol. 6, no. 1, January-April, 2015, pp. 155-166 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=402336276010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative THERYA, 2015, Vol. 6 (1): 155-166 DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237, ISSN 2007-3364 Una revisión del estado de conservación de los mamíferos australianos A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals John C. Z. Woinarski1*, Andrew A. Burbidge2, and Peter L. Harrison3 1National Environmental Research Program North Australia and Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environmental Science Programme, Charles Darwin University, NT 0909. Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (JCZW) 2Western Australian Wildlife Research Centre, Department of Parks and Wildlife, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, WA 6946, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (AAB) 3Marine Ecology Research Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (PLH) *Corresponding author Introduction: This paper provides a summary of results from a recent comprehensive review of the conservation status of all Australian land and marine mammal species and subspecies. -

New World Extinctions: Where Next? Mammals: the Recently Departed

GERMANY BERING SEA Bavarian Commander I. pine vole 1962 EURASIA Stellerís sea cow NORTH 1768 CORSICA & SARDINIA AMERICA Sardinian pika Late 18th C. WEST INDIES CUBA MEDITERRANEAN Cuban spiny rats (2 species)* HAITI/ DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ALGERIA Hutia (6 species)* San Pedro Nolasco I. Cuban island shrews (4 species)* CANARY ISLANDS Red gazelle Arredondoís solenodon* Quemi* Volcano mouse* Late 19th c. Pembertonís Hispaniolan spiny rats (2 species)* deer mouse 1931 CAYMAN IS. Hispaniolan island shrews (3 species)* PACIFIC Cayman island shrews Marcanoís solenodon* OCEAN (2 species)* Maria Madre I. PUERTO RICO Nelsonís rice rat 1897 Cayman coneys (two species)* Puerto Rican spiny rats (2 species)* Cayman hutia* MEXICO Omilteme cottontail 1991 BARBUDA Barbuda muskrat* CARIBBEAN Little Swan I. Caribbean MARTINIQUE Martinique muskrat 1902 Little Swan Island coney 1950s-60s PHILIPPINES: Ilin I. Monk seal BARBADOS Barbados rice rat 1847-1890 AFRICA J AMAICA 1950s Small Ilin cloud rat 1953 Jamaican rice rat 1877 ST. VINCENT GUAM Jamaican monkey* St. Vincent rice rat 1890s Guam flying fox 1967 PACIFIC ST. LUCIA PHILIPPINES: Negros I. GHANA Philippine bare- OCEAN St. Lucia muskrat Groove-toothed forest CAROLINES: Palau I. pre-1881 backed fruit bat Palau flying fox 1874 mouse 1890 1975 GAL¡PAGOS ISLANDS San Salvador I. INDIAN OCEAN San Salvador rice rat 1965 Santa Cruz I. Curioís large rice rat* SOLOMON ISLANDS: Guadalcanal Isabela I. Gal·pagos rice rat Little pig rat 1887 Large rice rat* 1930s TANZANIA Giant naked-tailed rat 1960s Small rice rats (2 species)* Painted bat 1878 NEW GUINEA CHRISTMAS I. Large-eared Maclearís rat 1908 nyctophilus (bat) 1890 MADAGASCAR Bulldog rat 1908 Santa Cruz I.